Cricket’s flat-Earth view of swing bowling changed forever when Pakistan’s swing merchant threw the game into reverse.

Cricket’s flat-Earth view of swing bowling changed forever when Pakistan’s swing merchant threw the game into reverse.

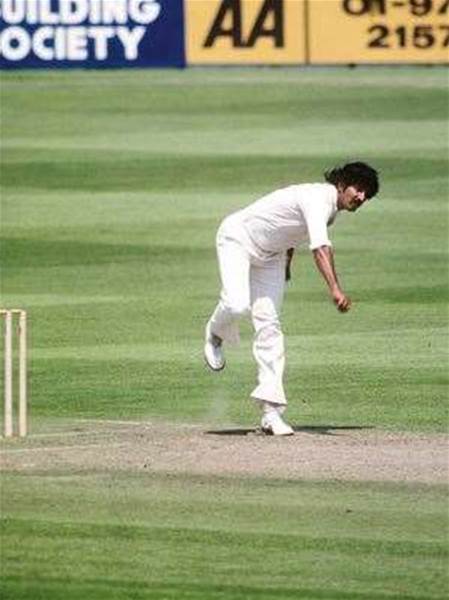

Australians remember Sarfraz Nawaz as the feisty six-foot-six Pakistani fast-medium who always took wickets against us;

the moustachioed bandit who deprived the Aussies of certain, easy victory at the MCG in 1978-79, when at 3/305, chasing 382, they were cruising, Border on 105, Kim Hughes 84. The Aussies needed a mere 77 more when Sarfraz unleashed such extraordinary and unexpected mayhem, questions needed to be asked – but since this was ‘78-79, no one knew what those questions might be.

It would’ve been like Copernicus, after hounding flat-Earthers with his observations about space, suddenly chucking the whole idea of time into the mix for good measure, 600 years before Einstein. No one had even conceived the possibility of reverse swing because, as with space-time, there was a relationship they hadn’t seen. Certainly, the expectations of batsmen weren’t geared toward a ball swinging in the opposite direction to the one they anticipated when they watched it released.

So Sarfraz’s breathtaking display of swing and seam was never reported as a masterpiece of this new, hidden art. From 3/305, Australia popped like soap bubbles to be all out for 310! Sarfraz took 7/1 in that unbelievable spell, and 9/86 for the innings.

A long time after Sarfraz retired, the lineage of reverse swing was traced directly to him. The story goes that Sarfraz, with fast-bowling partner Sikander Bakht, developed his theory that an older ball, weighted on one side with sweat and grime, would swing dramatically in the direction opposite to that expected.

Now, Aussies might remember Bakht as the skinny, bustling bowler who seemed to want to let a ball go a lot faster than he actually could. He wasn’t incredibly quick, but his run-up was so lively, it looked as though he’d beat the ball down to the other end if he kept running. However, on Pakistan’s very next tour after the controversial Australian stint, Bakht did to India, at home, what Sarfraz did to Australia: he demolished them with an unforeseen blitzkrieg, taking 8/69 and, like Sarfraz in Melbourne, 11 for the match.

Swing bowling, whether conventional or “reverse”, has always been about a ball of two halves, and the asymmetry of those halves.

There are three things about the phenomenon of reverse swing that distinguishes it from its orthodox counterpart. Firstly, it can be done with an old ball. Sarfraz had always been notoriously good with an old ball in his hands. Secondly, the swing can be dramatic, both in its extent and its lateness in the ball’s trajectory. Thirdly, it can only be executed by the faster bowlers. The threshold speed seems to be around 130km/h.

Since cricket’s beginnings, batsman have been dealing with the issue of deviation in the air, away from or towards them, depending on the way the bowler held the ball, the mechanics of his action, air moisture and other factors affecting aerodynamics. When it all came together, the bowler could bend it around corners, like Bob Massie, Terry Alderman or Damien Fleming. Conditions often played a big part, as well as the state of the ball, and the variation in its manufacture from one country to the next.

In the case of reverse swing, the state of the ball is the primary factor. Previously, when orthodox swing was the only swing, bowlers and fieldsmen would work assiduously to keep one side shiny, while the other deteriorated. The effect on a moving ball was obvious: the shiny side would facilitate its movement through the air, and the ragged side would act as a “brake”. This would cause the ball, at some point in its forward journey, to deviate sharply. Depending on how the ball was positioned – shiny side to the left or the right – the ball would stray accordingly.

Sarfraz found that, when one side of the ball is “weighted”, and the ball is delivered at good speed, it swings very late, and in the direction opposite to that expected: that is, it dips in with a traditional outswinger’s grip and sways out with a conventional inswinger’s grip. This took batsmen by surprise in the late 1980s and throughout the ‘90s. It took a while for the cricket world to catch on.

Sarfraz passed his esoteric knowledge on to team-mate Imran Khan, who in turn imparted it to Waqar Younis and Wasim Akram. With those two operating in tandem, cricket fans were often treated to breathtaking displays of bowling legerdemain. There is extraordinary film of Younis letting a ball go and getting normal swing as it leaves his hand, and reverse swing as it nears the batsman, shaping the delivery in an “S”, at high speed.

Glamorgan’s Simon Jones accepted the flame from county team-mate Younis, then Jones gave it to Andrew Flintoff, who decimated the Aussies with it during two Ashes tours in England.

Today, now that reverse swing is all the rage, we see strange things: we watch the ball get roughed up; we see the way it behaves as a consequence. We watch fieldsmen deliberately throw it in, short of the ‘keeper, or thump it into the pitch. And we see batting line-ups turned inside-out with old balls.

It all became so counter-intuitive after Sarfraz Nawaz introduced something of “opposite world” into the game.

− Robert Drane

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open