The concept of a Lingerie Football League might be ridiculous, but its athletes aren’t.

The concept of a Lingerie Football League might be ridiculous, but its athletes aren’t.

Adrian Purnell is asked a question that a footballer will periodically hear. What’s it like in the dressing room? Her answer, however, doesn’t exactly come from the field manual of press conference cliche. “There’s no pillow fights,” she says good-naturedly. “We don’t do sleepovers.”

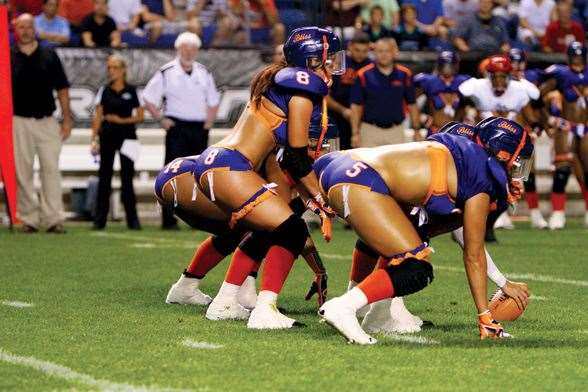

It’s not what you’d expect to hear from a footballer. But Purnell and her ilk aren’t exactly playing your usual kind of football. Minus the standard helmets and pads of the American code, she’s wearing a uniform skimpy enough to make a beach volleyball player blush. The backdrop behind her is emblazoned with the logo of the Lingerie Football League (LFL) which bears more than a passing resemblance to mudflap girl, that bumper sticker of a voluptuously feminine silhouette glimpsed on long-haul drives everywhere. After the questions, Purnell and colleague Chloe Butler eventually head outside onto the Centennial Parkland green to display their skills on the tackling bag. A PE class full of teenaged boys is stopped dead in its tracks, the visions in their heads rendered flesh, rather literally. It’s the latest example of what mashup culture has wrought. Combine two elements popular in their own right, and overcome any repulsive forces with deft manipulation of the packaging. You could never go wrong banking on the enduring popularity of football or attractive women. But somehow, when you put the two together, it verges on transgression.

If “touchdown-scoring babes” has a touch of movie-studio thinking to it, then it should come as no surprise that the LFL is based in West Hollywood. The league is the brainchild of Mitch Mortaza, who started out with the idea of staging a one-off event as an alternative to the Super Bowl half-time show. The first Lingerie Bowl was played in 2004 – by an incredible coincidence, that was also the year that Janet Jackson’s breast was exposed by Justin Timberlake in the infamous wardrobe malfunction. The overheated reaction to the incident prompted the NFL to stock the big game’s half-time with safe, ageing rock acts, and the Lingerie Bowl had the field of sexed-up pigskin to itself.

The Lingerie Bowls were enough of a success – three were held, and as a pay-per-view property, they compared well to boxing bouts or wrestling manias – that Mortaza began thinking of expanding the concept. After going dark for three years, the Lingerie Bowl reappeared in 2009, along with the newly minted LFL, which saw ten teams across the country play 24 games over five months. The names of the teams weren’t exactly subtle: San Diego Seduction, Dallas Desire, Los Angeles Temptation.

If there’s one thing that the LFL doesn’t lack, it is media savvy. It’s hard to see any separation between the sporting product and the media production and in this manner it shares genes with other sports entertainment ventures of the day such as the WWE and UFC. Like those two, it quickly invokes the great claim of the low-base riser – “the fastest-growing sports league in the United States”, affirmed by Businessweek magazine. For a new sport it has an established foothold on television through MTV in the US and Fuel TV in Australia. This year’s Lingerie Bowl drew 43 million viewers worldwide.

Founder and chairman Mortaza looks the part of mogul: blue blazer, no tie, loafers, deep tan. He speaks in underdog terms: “Nobody thought it would get on television. Nobody thought an arena or stadium manager in their right mind would ever play this sport in it. Certainly, you wouldn’t find models willing to put their bodies on the line and play a really intense game of football.

“What started out as almost a taboo sport, if you will, is turning mainstream. In a little under three seasons, to put in perspective, we’re outpacing where WWE and UFC were through their first three seasons. Mind you, it’s a women’s sport on top of that.”

The counterpoint follows quickly. A women’s sport – played by women, but for women? The LFL has put itself out as a lightning rod for criticism, running up against not only the charges of blatant double-standard sexism, but also the innate conservatism found in football culture. Mortaza has had plenty of practice at his response.

“When I get asked that question, the answer is that most people haven’t seen a game, haven’t been to a game; they’re basing it off the term ‘Lingerie Football League’ and that’s understandable. When you go to game, what you’re going to see are incredible athletes that take the game seriously. We certainly use sex appeal to initially sell the product, bring media attention to it. But unless it was a real game and we were serious about the athletics, we wouldn’t have a shelf life.

“Does it objectify women? I don’t think so. These are all educated women, we have military personnel, mothers, doctors, lawyers. There are 9-to-5 women who are high-level former collegiate athletes. They wouldn’t allow themselves to be objectified.” It may be taboo, but it’s a taboo that the world outside of the US understands.

The NFL has long struggled to export its game, but the LFL is pushing quickly into global expansion. Its first steps in Australia, with a pair of all-star games in Brisbane and Sydney this June, coincide with the beginning of league play in Canada (team names: Saskatoon Sirens, Regina Rage). The plan is to set up a four-team league with franchises in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth, which will play in the summer of 2013, and an equivalent league will be set up in Europe. (No doubt we’re all excited about the potential team names.)

They’re grand plans for a league which in the US is navigating a season switch, from autumn to spring, and has had issues with franchise turnover (six of the teams from the LFL’s early years have folded, although the league has grown to 12 franchises). Mortaza characterises those issues as “growing pains”, locating teams in cities that were great to have a cocktail in, but not necessarily football towns. In the case of Oklahoma City, it was outright denial, as mayor Mick Cornett said the LFL could not play in either of the town’s two municipally-owned venues, stating, “There are too many problems to list. There are so many that I don’t want to gravitate to just one.” Mortaza’s response: “I though our plans were for expansion into Oklahoma City, not North Korea.”

In crossing the equator, Mortaza’s hoping to find a bunch of football towns. “I’m trying to find out more about the football culture in Australia,” he said. “One of the things I do know, they’re passionate, fanatical-type fans. And if you want that audience, you’re not going to get it unless it’s real football and the girls take it seriously, they train, and it’s fierce. “At this stage at the infancy of this brand, there are a lot of misconceptions, similar to when UFC launched – human cockfighting, they’re still fighting that ... There are strong similarities between our brands. It’s funny to see our progression follow their suit. We think ultimately we’re more commercially viable because we’re dealing with beautiful women in an intense sport. But the girls don’t have cauliflower ears.”

Eventually, the various LFLs in the US, Australia, Canada and Europe will get together in 2014 to contest an international title. True to its roots in counter-programming, the game will be played in Sao Paulo, Brazil, the week of the FIFA World Cup final. And surely you won’t find Brazilians complaining about how scantily clad the players are ...

Talk to Chloe Butler for any length of time and it’s the most convincing case for why this game is not Gladiators. There’s no put-on bluster, just the can-do competitiveness of a sports-loving country girl from Croydon in Far North Queensland. Butler, whose significant other is Canberra Raiders hooker Travis Waddell, was a serious track athlete, a 400m hurdler who moved to the capital to train at the Australian Institute of Sport. “I love running and I still run, but I had four stress fractures in a row in my feet. I had to admit that I can’t run anymore,” she says. “Living in the AIS, when I lost my spot, I started cheering mostly for socialising. I was a gymnast before I was a runner, so I always liked the acrobatics. “I found football. Started playing rugby with the Brumbies [women’s sevens team] and heard about the league and went over to America. I was doing a modelling event on the Gold Coast with Playboy, and I met some girls from LA. They asked me what I did, and I said I played a bit of rugby. And they said, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re perfect for this league in LA, you’ve got to try it.’” After contacting the team in Los Angeles, Butler sent a YouTube reel of her rugby exploits. Also on the video was footage of her completing drills that every football player in America knows too well, a piece of inside information passed along by Jesse Williams, the Queensland-born defensive juggernaut of the University of Alabama, the current national college football champion. Word of mouth put the two in touch. “He was like, ‘Hey, I’m going to the States, this is what I did,” Butler says. “‘I can set you up with the same kind of project,’ because he knew all the drills and what they wanted. When I did it all, and I showed them my contact side in rugby, they were like, ‘Yes, please come.’ “But when I got there, I was continually trying for my spot. Every week, you have to prove your spot; it’s never a given. Especially in LA – there are a lot of girls who want to be in the limelight. They’d always threaten us that they could replace us like this [clicks her fingers], that they would go down to the CrossFit Gym and pull a bunch of women out and they’ll be back to drop them off if you don’t want to play, if you don’t want to hit, if you don’t want to step up.”

It harkens back to the seat-of-the-pants days of pro sports, before it became too respectable a business. Adrian Purnell’s experience in coming to the LFL was similar. A former track athlete who played flag football when her Florida high school started up a team in her last year, she headed to the league’s open tryout for the Tampa franchise, the Breeze.

“It’s a long process, but you have to weed out the good and the bad,” she says. “And a lot of girls need training because we, as girls, have never played football in school. The first one I went to, I was very intimidated. My coach always tells me I’m like a reindeer, I’m very out of control, but slightly in control. He’ll tell you to this day, I almost didn’t make the team my first year because I get so nervous.”

Purnell idolises the Baltimore Ravens’ star linebacker Ray Lewis, which is unusual – kind of like finding out the cute girl you were hitting on at the bar had Paul Gallen for a role model. As her team’s middle linebacker, Purnell’s job is to see where the ball is going and hit the person carrying it. Butler plays on both sides of the ball, as a pass-catching receiver and defensive end.

The game itself can best be described as the rugby sevens version of gridiron – it is seven-on-seven, for a start, with the four players removed from the standard 11-man line-up being the hulking linemen. Before you become suspicious of the reasoning – there’s no way that lingerie football would want such players on its field – bear in mind that seven-on-seven is a burgeoning football variant in America, with promising high school players engaging in such competitions in their off-season.

This stripped-down (pardon the pun) game, played indoors on a 45m (50 yards) field, is one that has marked differences to the full version: fast, skilful and multi-dimensional, divorced from the overemphasis on power and narrow specialisation one sees in the NFL. (About the only criticism you could make is to quibble with the term “football” – there are no field goals or punting, so no need to use the foot at all.) It looks, dare we say, like real sport. The fixation on the packaging, or lack thereof in this case, obscures that fact. For its part, the LFL straddles a difficult line – asking for it to be taken seriously, while presenting itself in a manner that near guarantees that it won’t be.

There’s another way of looking at this. It’s not so much the issue of why women are playing professional football in lingerie, but the prior question of why women don’t get to play pro footy at all (give or take a few soccer leagues). Interestingly, both Butler and Purnell are long-time cheerleaders – the former for the North Queensland Cowboys and Canberra Raiders, the latter having yelled “go team” between the ages of seven and 18. The culture has deemed it acceptable for women to wear outfits and stay on the sidelines, but not move into the middle.

“I feel like in the community with those topics, it’s like a half-glass story,” Butler says. “You can look at it either way. “Being a cheerleader on the side is accepted, which I think is worse. The thing is, women don’t have the same platforms as men in sports. I know a lot about the NRL because my partner’s playing in it – you could be a not-so-good-looking guy and still be able to be marketed. For women, it’s harder. You have to play with the hand of cards that you’ve been dealt. In the entertainment industry, sex appeal is what’s been deemed successful.”

There’s a hint of resignation in Butler’s voice, an acknowledgement of the deal she’s making. It’s an opportunity, a rare one, to craft a sports career. She excitedly brings up the prospect of rugby sevens ascending to Olympic status at Rio 2016, and the thought that she might be in the frame for that team. It’s a heady thought – from World Lingerie Bowl in Brazil to Olympic Games in Brazil two years later. It would be one of the most unconventional stepping stones to Olympic glory. For the cynics who believe the LFL is the province of attention-seekers, it has to be said that there are easier ways to get noticed.

“If you’d only want it for exposure ... or want a modelling contract, you wouldn’t last,” Butler says. “The girls involved in this league have a high pedigree of athletic background. I have a girl in my team who runs a time faster than any Australian girl in that event. These chicks are real athletes. I’m using it to become a professional athlete ... That’s what I’m using it for.”

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open