Not every player can claim their title was a reward for patience and club loyalty.

A restaurant in Melbourne serves up discards and offcuts – stems of broccoli or cauliflower, for example, rather than the flower which is the common gustatory fancy. Their reasoning: stems are rigid and tough because they draw from the soil, and therefore the most nutrient-rich part of the plant. Kale is coarse, chewy and durable, like a weed, which also suggests health-giving properties. They were serving it long before it became trendy “paleo” food. Footy clubs can be like conventional restaurants, choosing ingredients according to the dictates of current taste. But certain clubs, some of which feature in this year’s finals series, see the nutrition value of players, and make a habit of recruiting with one thing in mind: health. And it doesn’t get much healthier, or tasty for that matter, than a premiership.

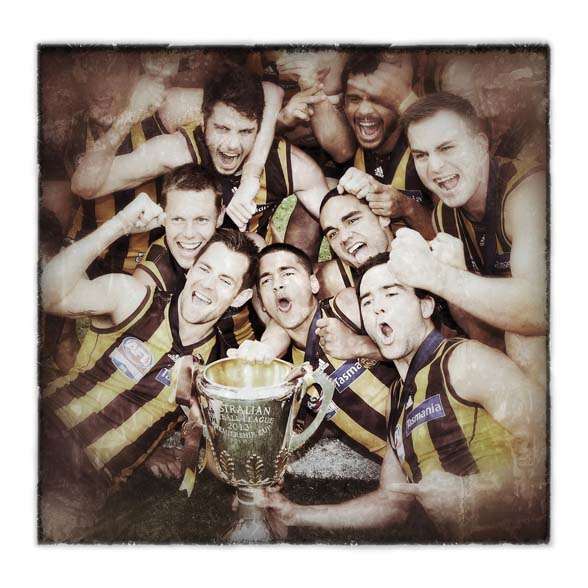

HAWK EYES

Hawthorn’s recipe for success has, since 1961, been the most effective in AFL/VFL history. They recruit judiciously, growing their own hearty champions. When they see an opportunity, they’ll pluck a hardy, if ageing, herb from elsewhere and he’ll turn out to be just the ingredient for the most flavoursome feast of all: a Grand Final victory – the sort of repast the player himself might never have conceived.

The Hawks have always been good at giving chances – in some cases, second, even third, chances. In others, an unlikely first. Sam Mitchell is today’s most documented example. Mitchell, dismissed as simply not good enough by the several AFL clubs he’d approached, is a three-time Premiership winner, and counting. He was also the 2008 Premiership captain, living proof of Woody Allen’s observation that “80 percent of success is turning up.”

Ian Bremner became a vital component of Hawthorn’s 1971 and 1976 Premierships, despite being thrown off by Collingwood after just one game. After six fruitless seasons with St Kilda, Russell Greene made the luckiest decision of his life on the eve of another Hawthorn renaissance. Everything remarkable about his career happened after he crossed to the Hawks: All-Australians, MVP awards, B&Fs and, of course, the 1983, 1986 and 1988 Premierships. Good move!

With recruiting insight matched only by Paul Roos, current Hawthorn coach Alastair Clarkson has given and taken many a chance, for excellent returns.

Brent Guerra voluntarily left Port Adelaide in 2003, was delisted by St Kilda in 2005 and selected by Hawthorn at Clarkson’s request. He retired with two medallions in the cabinet. Jonathan Simpkin had been delisted by Sydney and Geelong. With four games to his career, he was scooped up by Hawthorn, and now his 36 career games include the 2013 title. Josh Gibson concluded a faltering career with North before joining the Hawks in 2010. He now has the 2013-14 trophies in his cupboard. David Hale was disposed of by North when they decided they didn’t need a goal-kicking ruckman. Two titles later, he’s glad he went to Hawthorn, thanks again to Clarkson. Jack Gunston left Adelaide, homesick for Melbourne, after only 14 games; he was stripped of Adelaide’s best first-year player award when they heard he was leaving. Hawthorn were only too glad to get him. He’s played in both winning Grand Finals since, and was one of the best on each occasion. Shaun Burgoyne never thought he’d add another bauble to his collection after Port Adelaide’s 2004 win. But Clarkson wanted him, chronically injured though he was, in 2010, and he’s since added two.

Hawthorn has taken great risks, but only after rigorous calculation. As a result, they’ve consistently fielded some of the best teams the game has seen. The radiant success of their recipe has been founded on a solid basis of sound decision-making. Their system has been so foolproof that a stand-in coach, Alan Joyce, could walk into the job and take them, or ride with them, all the way.

Where Hawthorn has excelled in recent years has been the recruitment of established players with plenty – or in some cases, just enough – left in the tank to help them over the line. Two examples are Stuart Dew and Brian Lake.

Dew was a key reason for Port Adelaide’s 2004 win. He retired, limp, limping, almost spent, in 2006, and left football completely. Then, in 2007, vitality renewed, he announced a comeback to choruses of “the game’s moved on, mate – no-one wants your type anymore.” Hawthorn took him. His hamstrings rebelled. With 13 games in 2008, it was doubtful he’d be selected for the finals. The critics were satisfied: ad hoc picks don’t win Premierships, they said.

Dew was thrown into the Grand Final recipe and proved a piquant addition, his dazzling burst of two successive goals and two goal assists during a crucial phase of the third quarter turning Hawthorn’s fortunes. At game’s end, Dew was a two-time Premiership player.

In 2013, the Hawks were at it again. Brian Lake was a champion rebounding defender who’d subdued most of the game’s best forwards at the Western Bulldogs. But most hard-arsed pundits discounted him as chronic knee injuries threatened. He was 31. The lowly ’Dogs willingly traded Lake in 2012. Hawthorn – again under Clarkson – took the punt. It was widely considered a mistake. Clarkson had surely got it wrong this time. Sure enough, the injuries didn’t go away and Lake didn’t play until round five. But at the conclusion of the winning 2013 Grand Final, the inconceivable had become reality. Brian Lake had a Premiership, and the Norm Smith medal around his neck for B-O-G. In 2014, he became a dual Premiership player.

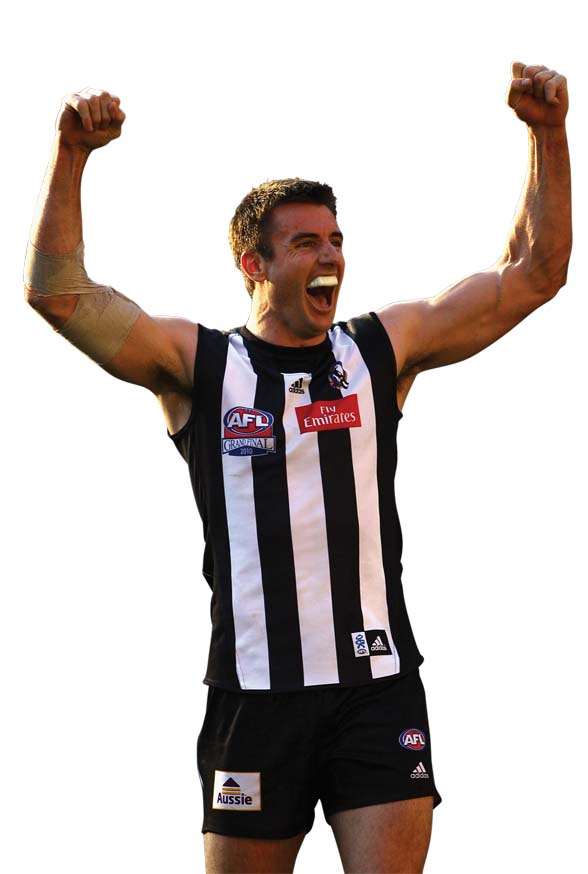

PIE TIME

Collingwood have always backed their choices with loyalty and perseverance. Darren Jolly, like Dew, had already won a Premiership, but was generally considered “past it.” The ’Pies picked him up from Sydney, recognising him as just the ingredient they needed. He’d begun an itinerant career with Melbourne, where he spent much of his time as second-string ruckman to Jeff White. After four seasons, he only managed 48 games. He was traded to Sydney for 2005, installed as a vital member of their ruck division, and wound up with a Premiership that very year. Unable to recapture their magic of 2005-06, Sydney traded him in 2010. He promptly won another with the ’Pies, again in his first year. In both cases, his team played the Grand Final the following year, and lost.

Jolly was no mere privileged passenger. In 2010 – the first, drawn game – Jolly got the tap out in that opening Grand Final ruck contest that is always accompanied by the most colossal crash of crowd noise. The ball made its way quickly toward Collingwood’s goal square, where Jolly launched his bulk, marked, and goaled. How he got there so swiftly no-one knew, but he immediately stamped his presence. This man knew how to play a big game.

Four Grand Finals, two Premierships – not bad for a ruck discard who began as second-stringer at a third-rate team!

Collingwood also got Luke Ball for 2010. Ball’s lack of a Premiership medal wasn’t for lack of trying. He’d been prodigious for St Kilda, Collingwood’s opponents that Grand Final day. Saints had made a few raids on the Premiership, unsuccessfully. Ball had been an excellent captain and leader, an all-Australian midfielder in an era of superb midfielders. The previous year, 2009, he’d stood amidst the Saints’ miserable huddle as they digested a 12-point loss to Geelong in the Grand Final.

He, too, had been troubled by injury, and was generally suspected to be past his use-by date, despite a lucrative contract on the table from St Kilda. He was determined to leave, and Collingwood was his choice. At the end of the 2010 Grand Final replay, he stood victorious – a Premiership player at last – but feeling, keenly, the pain of his old teammates as he looked across at that familiar huddle. There, but for the grace of footy’s gods ...

NORTH TO GLORY

Serendipity, a recruiter’s whim, a coach’s peremptory wish. Unforeseen paths to Premiership glory can suddenly, magically, open up for a player. In 1973, defection was almost unheard-of, until the original defector, Ron Barassi, became North Melbourne coach and promised Premierships to the club and an assortment of down-and-outers, ham-and-eggers and brigands who’d never contemplated the idea. There would be no “rebuilding” – not for a dynamo like Barassi. The minute he arrived at the perpetually-impoverished Shinboners, he took swift advantage of an ephemeral initiative called the ten-year rule (which enabled players who’d served ten years at a club to move on unimpeded), and held the lure out to a band of champions.

Barry Davis, Doug Wade and John Rantall were North’s Big Three. Davis was a prolific, smart Essendon backman who’d done everything a Team of the Century player could do: two Premierships, three best-and-fairests, two years as captain. After 218 games, he had all the hallmarks of a one-team player, but as in the case of most evergreen champions, speculation rose like a miasma. He was 30, after all. Who’d have believed what he was about to achieve?

Wade stands with Lockett, Ablett senior and Dunstall as a player with over 1000 career goals – a big, powerful legend of a full-forward. He was 31, and after 208 games with Geelong, he, too, looked like a one-team man until the call from his old rival, Barassi. He spent three years at North, and the pointy end of his career turned out to be the pointiest of all.

John “Mopsy” Rantall was already a South Melbourne legend. Unlike his two cohorts, the magnificently skilled defender never experienced a Premiership, but deserved one. Brent Crosswell had already won two medallions with the Blues before Barassi got him across to North just in time for the Premiership year.

Grand Final 1975, they all shone. Wade produced an extraordinary display of Grand Final generalship. Davis became a Premiership captain. Rantall was unbeatable; Crosswell, best-on-ground.

That Grand Final was a grand finale for Wade and Davis, who retired after the win. Rantall returned to South. Crosswell won another with North in 1977.

Barassi also looked to the west and gave some of the game’s best players, like Barry Cable and Malcolm Blight, their chance at a Premiership and fame, at a time when playing in Victoria was the only path to recognition for a deserving footballer. There have been many other instances of South and Western Australian recruits winning Victorian Grand finals, and often being the difference, during brief, shining AFL careers: Peter Bosustow, Polly Farmer, Cable and Blight are outstanding examples.

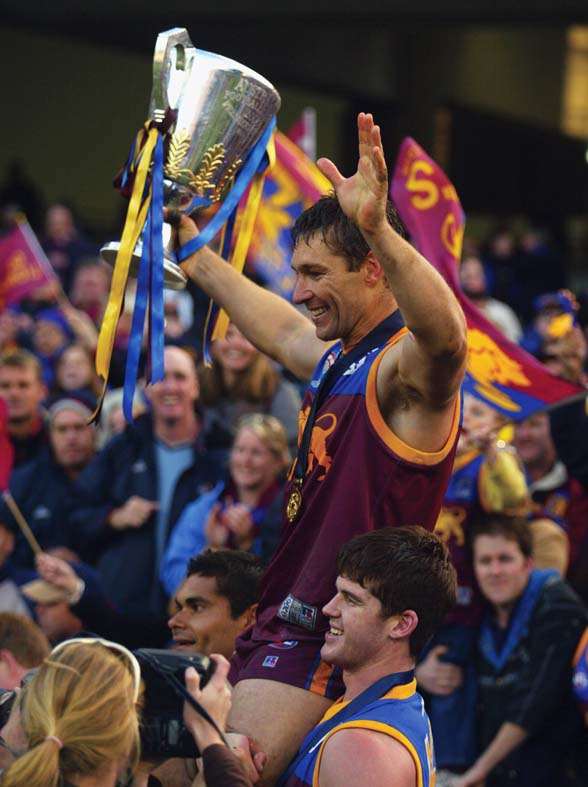

EYES ON THE PRIZE

Some stumble upon the right place; others are led there. Many steer themselves. Two modern instances of providential “desertion” were Justin Madden and Alastair Lynch. Madden left Essendon because the ruck position was occupied by the greatest of ruckmen: his brother, Simon. Justin’s time at Carlton led him to be considered a ruck hero in his own right. On top of that, he collected the 1987 and 1995 Premierships.

Lynch left struggling Fitzroy before they merged with Brisbane. At the time, in 1994, Brisbane were still the Bears. The versatile and powerful Lynch was All-Australian full-back, and a goalkicker up the other end. All three Premierships with Brisbane came when he was well into his 30s, as Lynch’s career had, since 1995, been frequently interrupted – and therefore probably prolonged – by chronic fatigue syndrome. In 1994, he’d never have imagined he’d be a key member of one of AFL’s most formidable and accomplished Premiership-winning teams – for three consecutive years.

A man often mentioned in memos when greatness is discussed is Greg Williams. Overlooked by Carlton as a youngster, “Diesel” went on to shine at Geelong and Sydney, where he won a Brownlow in his first season. But no Premierships were in sight. By the end of 1991 he was restless for a return to Victoria. The Blues this time wanted him. Badly. They acquired him via a three-club deal. Williams played six seasons at Carlton, winning another Brownlow and collecting the famous ’95 premiership win – and, of course, the Norm Smith medal.

THE DISCARDS

Many with CVs including Premiership honours were true discards. Their clubs were only too glad to bin them before some recruiter’s intuition had them suddenly floating in a new soup, their late addition just the dash of flavour needed to enhance, or complement, more highly-regarded ingredients. A discard’s lack of ability to add savour or nourishment might be soon found out but for the winning Premiership recipe they find themselves part of.

But good coaches extract maximum contribution. In fact, some make the critics rave with a recipe made almost entirely of cast-offs.

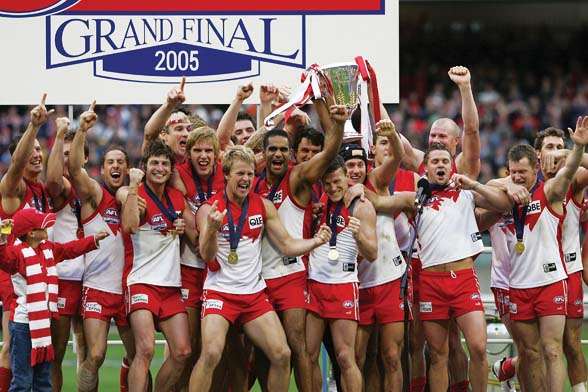

This was the key to Paul Roos’ success in 2005, when he took an unlikely bunch to victory. The surprising Roos took a leaf out of the Hawthorn book, declaring, “Send us your rejects, your released, your refugees, your retirees, your refusers, your recycled, and we shall make Premiership players of them.”

Added to Roos’ sound coaching philosophy were little glints of insight, like arrows of silver. Roos was uninterested in bottoming out to get the best of the draft. No longer would Sydney rely on “names.” They won that miraculous Premiership with footballing flotsam, none of whom would have envisioned such dizzying success when they joined: Tadgh Kennelly, a top Gaelic footballer, was part of the Irish experiment. Craig Bolton, disposed of by Brisbane after making it as far as a Grand Final emergency twice during their Premiership years. Amon Buchanan, delisted by his own club before Roos redrafted him. Captain Barry Hall, who left St Kilda to make way for a band of young forwards. Paul Williams, a good player in a mostly-unsuccessful Collingwood side before being traded to Sydney. His 294 games were, to that point, the most played before picking up a Premiership medallion. Nick Davis, the goal-sneak traded by Collingwood at the last minute in a deal that cost the half-reluctant Swans a second-round pick. The aforementioned Darren Jolly, who’d left Melbourne with a slender reputation and a lot of unknowns.

In 2012, John Longmire, who’d taken over Roos’ role, was continuing the tradition. It led to another cup. Mitch Morton must have been rapt. The hard-working goal-kicker had been twice rejected, by West Coast and Richmond. Not many endorsed the decision to throw him into the Swans’ broth. But it only cost them a pick 79. He was cheap. Longmire almost drew laughs when he declared Morton would add “depth and firepower.” Morton was even dropped for round 23. He battled in reserves, got the call, played a great finals series, and collected himself the 2012 Premiership.

Rhys Shaw had been traded by Collingwood at the end of 2008, thus missing out on the ’Pies’ 2010 Premiership. Ted Richards was an Essendon cast-off; Martin Mattner was a journeyman who’d done his dash, it was believed, with Adelaide. Then there were Lewis Jetta, overlooked in the 2007 draft; Shane Mumford, dropped by Geelong in time to miss out on their 2009 Premiership; Josh Kennedy, who, despite his Hawthorn pedigree, missed out on their 2008 Grand Final win and was traded after a mere 13 games; Canadian rugby union international Mike Pyke, derided as a “joke” when he first played AFL. Every Swan deserved his medal. There were no passengers. It was another astonishing, unlikely Premiership victory over a terrifyingly good opponent.

If Roos had begun as Sydney coach earlier, he’d probably have gone after Mal Michael, delisted by Collingwood in 2001 after 61 games. Papua New Guinea-born Michael was traded to Brisbane in 2000. By the end of 2003, he was a triple-Premiership player, lauded as a full-back sensation.

BACKDOOR CHAMPS

James Podsiadly came to own a medal via an unusual route. He was 28 when selected by Geelong as a mature-aged rookie, having taken a role as fitness coach and player for their VFL side. He turned out to be a sensation – a natural cult figure – and though he was subbed off with injury in the second quarter of the 2011 Grand Final, he nevertheless deserved his medal.

When it comes to ratio of games played to titles won, three of the more remarkable stories come from Carlton.

Brad Pearce is a name few recall, but he was a four-goal hero in Carlton’s 1995 win. Delisted by Brisbane Bears in 1994, Pearce spent that year at Carlton mostly out injured. But his peak arrived suddenly in 1995, when his fast leading and accurate disposal contributed to a monster year for full-forward Steven Kernahan. As well as his own goals, Pearce continued this habit in the Big One. Injury ruined his next four seasons, and with only 77 games for the Blues, he retired, but not before playing a key part in a fabled Premiership.

Mario Bortolotto had the distinction of playing his first and last games for the Blues on the same days Peter Bosustow achieved those milestones. While Bosustow was flamboyantly winning games up front, Bortolotto was a considered a journeyman backman, recruited despite being dumped by Geelong after 14 matches. Carlton grabbed Bortolotto, remembering that he once mugged their star forward Mark Maclure. Though he mainly warmed the pine in the 1981 Grand Final, he got on the ground, and actually played a decisive role in ’82, holding the much bigger David Cloke to a few possessions, yet he only made that Grand Final side after full-back Rod Austin sustained a training injury. Mario’s tally at Carlton: two sporadic seasons, 30 games, two Premierships.

Ted Hopkins was not a footballer of great success. But he was a man of value during his team’s hour of need. In 1970, Carlton’s Grand Final was looking decidedly unappetising by half-time. They trailed by 44 points. We all know about Jezza’s famous mark, and Barassi’s half-time injunction to “handball, handball, handball.” But Carlton’s fare had been bland, in need of zest. Otherwise it was all over before dessert. Hopkins was a 21-year-old who considered himself lucky to be anywhere near the first 18. His sudden half-time elevation was no fluke. But it was a roll of the dice.

Carlton kicked seven goals in the first 13 minutes of the third. Hopkins had three and set up another for Jesaulenko. For a brief, exhilarating time, the 1970 Grand Final was flavoured with a dose of Hopkins. Collingwood’s faithful reached for their Footy Record in a flabbergasted attempt to find out who this smallish blond kid was. Hopkins tore Collingwood up with four goals, set up a few more and just missed a fifth. Then, Premiership medal around his neck, he retired to take up snow skiing and poetry and founded Champion Data, Champion Books and Backyard Press. His tally: 29 games, one Premiership.

Josh Kennedy was traded for Chris Judd an aeon or so ago. If he'd won a premiership this year, some might've wondered if the trade was a blue ... (Photo by Getty Images)

Josh Kennedy was traded for Chris Judd an aeon or so ago. If he'd won a premiership this year, some might've wondered if the trade was a blue ... (Photo by Getty Images)2015 TRASH TO TREASURE

Of the teams most likely to give the 2015 finals a shake (leaving out Sydney and Hawthorn), here are the candidates for this year’s “trash to treasure” award.

Richmond are the joker in this year’s pack. By finals time, they might surprise more fancied sides with their gathering potency. If they win it, a few throwaways will be vindicated. Ivan Maric, a former basketballer, came to the game late. Maric saw the writing on the wall and left the Crows in 2011. Now he’s an influential leader at Richmond, and a key to their recent success. Shaun Grigg saw little action with Carlton, received faint praise as an under-sized ruckman and was traded in 2011; every season since, he’s grown in stature. Big Shaun Hampson, who had dodgy eyesight corrected in 2012, was traded by Carlton in 2013; now he’s an invaluable ruckman/key forward. Bachar Houli was traded by Essendon after limited opportunities; he’s now a bold attacking defender for the Tigers. Taylor Hunt floundered at Geelong; now he’s been a driver back and centre with Richmond.

This year, Fremantle’s Zac Dawson might become a Premiership medallist, but even membership of Ross Lyon’s “perpetual runner-up” club would be better than what might have been. Dawson played 14 games for Hawthorn and 63 for St Kilda. He came close for Saints. They lost by 12 in 2009, and in 2010, the year they played Collingwood, he was St Kilda’s player of the finals. As a vital link in Lyon’s “defensive chain”, he followed Lyon to Freo.

Danyle Pearce had a 154-game career at Port Adelaide. Having just missed Port’s 2004 Premiership (he debuted the next year), Pearce saw some sparse years there. He was one of the first beneficiaries of limited free agency when Fremantle made a bid in 2012. Luke McPharlin had a so-so career for Hawthorn before moving to Freo in 2002. Known for taking spekkies and as one of the original “swing men” who can play at either end, he’s been invaluable to the club. At 33, he’s decided on this one last season. Will it be the one?

For Western Bulldogs, Matthew Boyd, at 33, will be glad he played on if the ’Dogs win this year. He’s risen from draft reject to exceptional possession-winner. Stewart Crameri had a bright future at Essendon, blighted by the drug scandal; for 2014, he was traded to the Bulldogs. Tom Boyd will only be too glad to be gifted a Premiership, after hype, ridicule and angst accompanied his purchase by the Bulldogs from GWS as the highest-paid recruit of all time.

If West Coast win this year, Josh Kennedy’s bitter trial will have become a blessing. Kennedy (not the Sydney player mentioned earlier), unwillingly packed off to the Eagles in the high-profile trade for Chris Judd, has developed into one of the best key forwards in the competition, capable of devastating multi-goal bursts, such as his 10 straight against Carlton (!) early this year, leading those who were disenchanted with Judd’s stint at the Blues to wonder if the trade had been a mistake.

As he kisses his Premiership pendant, Kennedy might feel relief that he didn’t get his wish to stay at Carlton. There are times when achievement in one place can prevent greater achievement in another. The path takes many twists, we leap at shadows, and sometimes, all the talent in the world won’t get us there unless time and place, blind as they are to our worth, choose us.

Related Articles

Socceroo star's message to kids: Don't be an AFL player

Updated: AFLW Round 2 preview and schedule