St Kilda star drummed out of AFL for sipping wrong sports drink. Well done, everyone ...

His dreams, his reputation, were in ruins. Ahmed Saad sensed it in the crowded dressing-room the moment he locked eyes with the team doctor coming his way. “We might be in trouble here.” The words sliced through to the bone. An instant of disbelief gave way to terrible realisation, as though he’d been ambushed.

It was match day!

He’d gotten the timing horribly wrong. The protein drink he’d unthinkingly drunk before the game, against Fremantle in July 2013, was the usual; the one he downed before training most evenings; the one he used to replenish his strength after the gruelling ritual of Ramadan. Called Before Battle, it was the product of a company – Viking – owned by a mate. Saad had agreed to become product ambassador for the same reason he took up football: to help out.

Six days a week, the drink was approved by the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA). One lurking ingredient made it illegal on the seventh. Methyl synephrine HCL. The fact that it was deemed perfectly acceptable the rest of the week – the ambiguity of that message – offered some vague sense of mitigation.

Saad felt sick with guilt, but after all, it can’t have been anything serious. “I’ve never even had a sip of alcohol in my life,” he tells me as he prepares to resume training at St Kilda’s Moorabbin ground after his enforced layoff. Putting unclean food into his body, never mind non-nutriments, was against his personal credo, and an offence against his religion.

Those beliefs had given him an awareness of temptation that set him apart. He knew this enemy. He’d felt its pleasant pangs and heard its siren songs and knew where they led. He knew it well enough from a young age to understand overcoming it was not a matter of resisting, but of getting out of its way. Every exertion of his will was an expression of his faith – including the way he went about his football.

Saad immediately knew two things in his inmost heart: that his intentions were perfectly honest, and that he was about to be treated like someone whose intentions were perfectly dishonest.

He was unlucky. ASADA’s people had tested him a few times. Some players have never been tested, which leaves some muttering – never above their breath, of course – their doubts about the official criteria, and suspecting unofficial criteria. An agency like ASADA will always be open to such accusations.

The treatment of Ahmed Saad was ugly. Not many, in the media at least, seem to apprehend the totality of that ugliness.

The logic: what he did was not serious in the slightest. If performance-enhancing drugs were standard practice, his team-mates would have laughed if he’d pulled out a can of the drink containing a modicum of methyl synephrine HCL and announced it was going to help him play better. While one-off attempts to cheat are possible and should be punished (a recreational drug might serve as a performance-enhancer if taken during a break in play), you only ingest the serious stuff, the stuff that alters your body, the stuff that really heightens overall performance, if you have intent; repeatedly, as part of a systematic program. Those outcomes cannot be attributed to accidental ingestion any more than conception can be blamed on accidental sex. If the athlete is not guilty of knowingly cheating, at least someone in the chain is.

The law: intent is inadmissible. Actions must be viewed in isolation from such considerations.

Ahmed Saad's intent was clear. But the law remains steadfast in the face of common-sense. If it didn’t, we’d all think less of it!

Saad’s profound confidence in the innocence of his intention makes his submission to his fate, and his style in accepting it, all the more remarkable.

The tests came back positive. His heart sank, then his world collapsed.

******

Momentarily. No one ever expects Ahmed Saad to just give up. Apart from anything else, he’s a Muslim boy playing elite sport. In AFL there are only two, for good reason. Saad’s journey to that level has been the sort of unlikely story the media loves as much as it loves a scandal. He gave them both.

Saad was born in Australia but his Egyptian parents moved back to Cairo when he was eight. For the next six formative years, Australia and its way of life were almost forgotten to him. He did his schooling and played soccer well enough to pull on representative jumpers.

His father had returned to Egypt to look after his sick mother. His duty done, he brought the family back when Ahmed was 14. Ahmed was about to discover Australia for the first time.

He didn’t have much family here and returned to no friends. One uncle who’d played Australian rules patiently tried to teach him to kick the Sherrin. For poor Sharif, the games were more kick-and-fetch than kick-to-kick. “He played basketball under-21s for Egypt. I idolised him. I shadowed him everywhere. For him,” Ahmed adds with a self-effacing laugh, “kick-to-kick was torture. I couldn’t even drop-punt.”

His handling of the oval ball improved, but his improvement wasn’t at first fuelled by determination to master Australian rules. He didn’t really play much at school, and by his own admission, wasn’t all that good.

One day he wandered into the struggling Roxburgh Park club to make up numbers at the request of friends. He still didn’t have many at 16. He did it mainly for company. At that age, he played his first real game armed with just enough skill to make him look silly, he thought. But Craig Burrows begged to differ. Burrows, Saad’s first coach, saw something. With even rudimentary skills, he was “athletic and skilled enough to take speckies and make people look stupid”. In one game he kicked ten goals. Burrows had coached a lot of Middle Eastern kids. Many were naturals. What sets Saad apart is a bundle of attributes apparent the moment you meet him: a tranquil mind, wisdom, good humour and intense determination without the attendant grimness. He’s a humble learner. He has this world and its machinations in perspective. His sense of who he is and its rightness is unassailable.

Burrows urged him to try out with the Northern Bullants. That was no easy task. The club, a selective-intake AFL feeder, would no doubt have exuded that air of exclusiveness any smallish, ragged, inexperienced Muslim kid with very few of those valued skill-hours in the bank would find forbidding. Saad was different. Though humble, he never feels unworthy.

“I know I wasn’t invited,” he said. “Just give me a training session and if you don’t like me, I won’t come back.”

David Teague liked him already. The Bullants’ coach remembers Saad’s off-the-street appearance because of its uniqueness. Saad looks across the field thoughtfully at his St Kilda team-mates putting out the bins for training. “I made sure I trained pretty well that day.” The modest Saad had made an audacious statement. Teague, the sort of Aussie to reward boldness and willingness to “have a go”, became an advocate.

But having a go was tricky and demanding for a kid of Islamic faith. In these days of balanced nutrition, maximised efficiency and fulfilled potential, Muslim footballers must have a hard time keeping up. Ramadan is only one reason. Its laws dictate that no food is consumed between sunrise and sunset every day. This lasts a month.

Keeping it is in the heart. Saad knows there are ways around it, but doesn’t take them. “I stick to my beliefs closely.” It’s just the way his life is, he says with a cheerful shrug. He doesn’t judge any Muslim who takes those ways. In any carb or hydration-dependent sport, Muslims are advised to eat and drink. Many seek exemption from religious leaders, and it’s granted, as long as they make it up after Ramadan. Islam, like other religions, discerns between the spirit and the letter of the law. Aussie boxer Hussy Hussein had a problem with breaking the fast, but he did, and felt his heart was right. Saad wrestles no such dilemmas.

Australia has come a long way. Once, to an “Anglo” footy coach, Ramadan might as well have been rama-lama-dingdong. At the Bullants, lollies and biscuits were waiting for Saad as soon as the sun dropped. Today at St Kilda, dieticians work with him during Ramadan to ensure his diet sustains him throughout the fasting day.

Saad wasn’t selected in the seniors, but he tried his tail off. During the summer of 2009-10, he worked hundreds of arduous, solitary hours. Strength, power, timing and endurance came, and only a few rounds into the next season, he was not only a regular, he was attracting attention from heavy AFL recruiters. “They were saying, ‘Who is this kid? He’s come out of nowhere.’ They wanted to know if I could keep doing it.” He decided on another season at the Bullants.

At the end of that season, he was the VFL’s Best Young Player. He’d attended the AFL’s draft combine, and his numbers, which included camp-best times in the 20-metre sprint and second in agility tests, made even the most world-weary scouts take notice.

In Thailand with his team on a post-season trip, Saad got the text from St Kilda recruiting manager Tony Elshaug. Saints needed his speed and smarts around goal. They dropped five places in the national draft to pick him up.

This kid, whose development was so delayed he still jokes about difficulties punting with his left foot (“my only left-foot goal was a soccer kick”), so late he still experienced a little uncertainty about where he should position himself, found himself running onto the field with the very best exponents of a game he’d barely heard of six years earlier. He gets by on instinct while he’s learning; excellent instinct. “I try to play on it as much as I can. That’s why I got drafted and I don’t want to shy away from that. It’s my natural strength. But I’m far from perfect in terms of my whole game.”

At the time of writing, he’s managed about five full seasons of football. That’s it. This kid who, according to his own demanding schedule, considered himself no overnight sensation, was a meteor.

He had a good 2012, two of his goals being nominated for goal of the year. The media was willing to bestow some of its most treasured cliches almost instantly. He was an emergent “excitement machine” and, probably because of his swarthy Middle Eastern complexion, commentators were already employing their racial shibboleth, “silky”. His timing inside the rush of a midfield surge was beautiful; he was undaunted by attention, a shrewd freebooter who could pull off a heist with mellifluous ease in a split-second. His 2013 was also good. He came to be regarded much more highly than a 29-gamer ought to be. Then came the taint ... The “scandal”.

******

The day he was delisted by St Kilda in November 2013 was one of the worst of his life. His family couldn’t understand why his career was under threat; why he was being accused of things he’d never do.

Of course there was a tacit understanding that the club would pick him up again in the rookie draft once he’d done his time, but no one knows what a hiatus of more than a year from top-level sport might do. It’s been proven over and again: of those who leave the summit, few make it back.

The AFL had handed down the minimum ban: 18 months. During that time, as per the WADA stipulation, he was allowed no contact with the club that had been his home, his support, his social world for two years. This, for a few swigs of a product readily available from any local shop.

Methyl synephrine HCL, extracted from “bitter orange” and popular because of its similarity to the banned stimulant ephedrine (and commonly found in weight-loss supplements), is classified by WADA as a “specified substance” – that is, a substance a player might take inadvertently via medicine, over-the-counter drugs, or energy drinks. The code acknowledges there is “a greater likelihood” of a “non-doping” explanation when the substance is detected than there might be in the case of other substances.

According to WADA’s code, “specified” is a category introduced to give tribunals greater flexibility in cases where a “prohibited” substance is not the issue. Two-year bans could be reduced in such cases. To be excused from a two-year ban, an athlete is required to demonstrate how they took the specified substance and prove it was not intended to enhance performance or mask a performance-enhancing drug. Having been found guilty of taking a specified substance, a player can even escape with a reprimand. In other words, the AFL was not compelled to ban Saad for 18 months, and WADA’s Australian agency, ASADA, was not at all bound to seek the full two-year prohibition.

But Saad was caught in a complex web. In February 2013, the day the Australian Crime Commission announced that a club was guilty of performance-enhancing drug (PED) use, CEO Andrew Demetriou, in a moment of panic PR, declared the “line is being drawn in the sand”.

Two years earlier AFL operations manager Adrian Anderson had announced a “major crackdown” on PEDs, in which “stars” would be targeted. They had a season quota of 1000 tests to be performed, and were paying ASADA considerably for the service. This crackdown obviously didn’t go as well as they thought it might.

When it was announced Essendon was the club under suspicion, Demetriou allegedly called chairman David Evans to warn him in advance of the ACC investigation. This has been in dispute, but if true, it doesn’t sound like “line in the sand” behaviour.

But it’s certainly in keeping with behaviour around the subject of artificial, illegal performance-enhancement, exploration of which has been subtly, sometimes rudely, deflected for decades. Occasionally, a diffident and carefully worded newspaper story would half-mention the demimonde of peddlers hanging around clubs. Reports would sometimes emerge of atypical increases in the growth of players. Nothing would ever come of it. Over the decades, first individuals, then whole teams, would emerge having put on kilos of high-quality muscle in short timespans, which would naturally arouse curiosity. Or their playing behaviour would change radically, a la Essendon, 2012.

Reactions always held interest for those with a forensic bent, especially in the media: the howling-down of those who asked questions – even without accusation; legal threats; the focus on “recreational” drugs (a social issue) at the expense of performance-enhancing drugs in sport (an integrity problem), speaking of the two as though they were the same matter; presenting the sporadic exposure of cocaine or cannabis use as proof they were on to sport’s “drug problem”, while drugs related to cheating and deceiving the public were barely mentioned. Conflating, confusing, compounding, confounding. It should always have been simple; now it cannot be.

Essendon was exposed “pushing the envelope” in the first place, it’s now apparent, because desperate pollies in Canberra wanted to refract attention from the federal government’s electoral woes. But Essendon’s intention might not have been to cheat, either. Like Ahmed Saad, they were merely caught up in something bigger than themselves and, on “the blackest day in Australian sport”, were destined to be reviled, wrongly, as the ones who threw the switch.

In February 2013, the AFL issued this statement: “The AFL is aware of only two specific cases where WADA-prohibited PEDs may have been used in the AFL.” In the last 20 years, one AFL footballer, Richmond’s Justin Charles, has been found guilty of PED use. Given the supposed rigour of the procedures, he’d be surprised not one player has joined him.

The roaring silence of the dog that doesn’t bark has been noted. Ahmed Saad’s case is the best example of inadvertent consumption of a specified substance since Andreea Raducan was sent home from Sydney 2000 after being caught red-nosed with flu medication in her system. It’s also the best example since then of the cruel injustice legal over-generalisation can create. “No exceptions” policies have been known to obfuscate the issues they were designed to address. Those of us who saw such grotesquely excessive punishments as that meted out to Raducan as a sign of something hidden were vindicated years later.

Apparently not “comfortably satisfied” that Saad was not a drug cheat and a threat to the very honour of the game, ASADA went after him. He’d cheated, they declared, and should be dealt the full measure of the law. They appealed to the AFL to extend the original ban of 18 months to two years. This would have meant Saad would have been close to 26 when eligible to play again. He’d have missed an extra season, in effect. It would probably have finished him. The appeal failed, but did its damage. “We thought we’d been through the worst of it but after the appeal, I got my mum and my wife crying on the phone saying I had to go through it all again and worried my career might be over.”

Meanwhile, toxicology reports on methyl synephrine HCL at the time proved inconclusive.

******

Why would anyone who has moved in sporting circles fail to be sceptical? Sport, as with anything else wanted or needed by the public at large, is a devil’s treadmill of money, self-interest and impossible Keynesian ambitions of endless expansion. Deception and distraction oil its works. To sustain the myth that sport is a great, classless pastime that sets anyone on the track to champion if they have the will and prowess, performance-enhancing drugs are only occasionally mentioned in despatches to our youth; never hinted at in self-help homilies by those “successful” athletes whose main triumph has been their elusiveness.

No one’s blaming the AFL for perpetrating the deception, but, perhaps, for not recognising it. If anyone is going to deceive the general public – for money, or fame, or just to keep their job – integrity will always be the opponent. It can’t be broken down directly, but it can be nuanced, calibrated and re-defined; distorted so grotesquely that even the pursuit of Ahmed Saad can even be made to resemble a matter of integrity.

A recent report on cycling’s woes illustrates just how institutionalised deception can become. “The emphasis of UCI’s antidoping policy was ... to give the impression that UCI was tough on doping rather than actually being good at antidoping [author’s emphasis]”. The AFL is not the UCI, and no doubt its lack of clarity is not so deliberate, but it should understand that noises emanating from the whole AFL complex, and certain actions, arouse those sceptics.

Ahmed Saad was never going to win. Amidst all those phantoms the Essendon episode unleashed – phantoms it seems everyone would much rather have kept in their subterranean caverns – he was a straw man they could at least take a swing at.

******

Following his delisting, Saad spent mornings walking around ruefully waist deep in the water at St Kilda, coming to terms with the shame he thought he’d brought to his family, pondering this foreign direction his life had taken – and refusing to be taken down. “I can deal with it all on my own, but seeing my mum, my sisters and my wife affected by it, that hurt the most.”

He got married at the end of 2013. He got himself a personal trainer so he could learn how to maintain peak fitness while not playing the game he was getting fit for. He spent time with his wife. He studied and gained qualification as a stockbroker.

Ahmed threw $20,000 into the law’s insatiable maw before realising he’d have to be loaded to salvage a good name someone else had trashed. “Justice?” went the opening line of William Gaddis’ novel, A Frolic Of His Own. “You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law.”

He’s never blamed anyone but himself, constantly, at every opportunity. Sprawling on a pin, he was never going to escape detailed dissection under the media’s electron microscope. A genuine PED scapegoat was too good to pass up. They extracted contrition, even recommended “education.” After all, it was a chance for them to look tough on cheating as well.

But his media appearances were no PR exercise. He owned his guilt. His unemotional self-blame was almost frustrating.

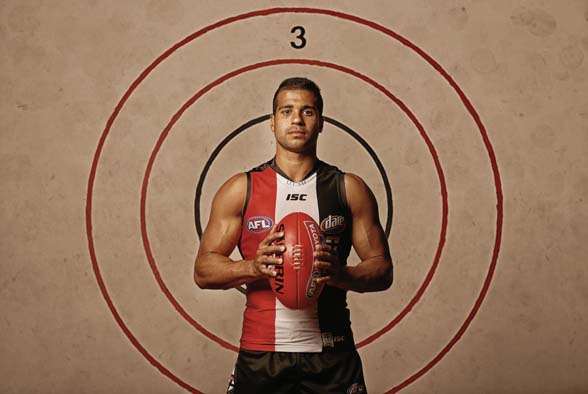

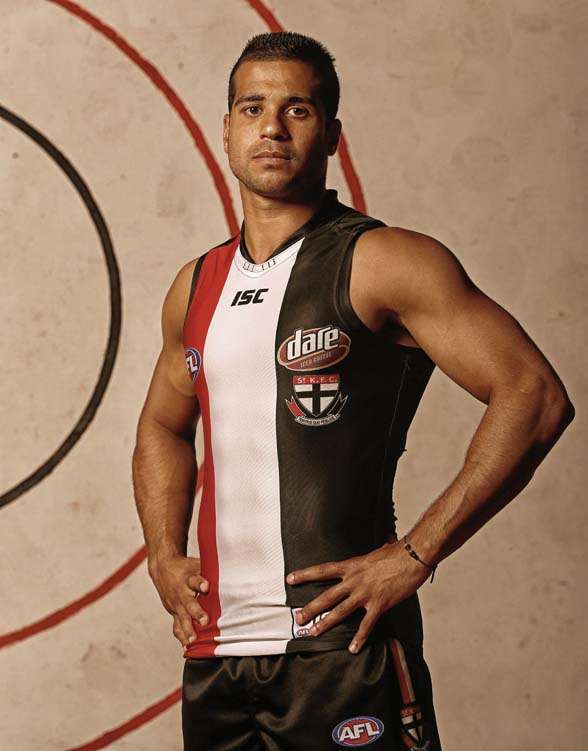

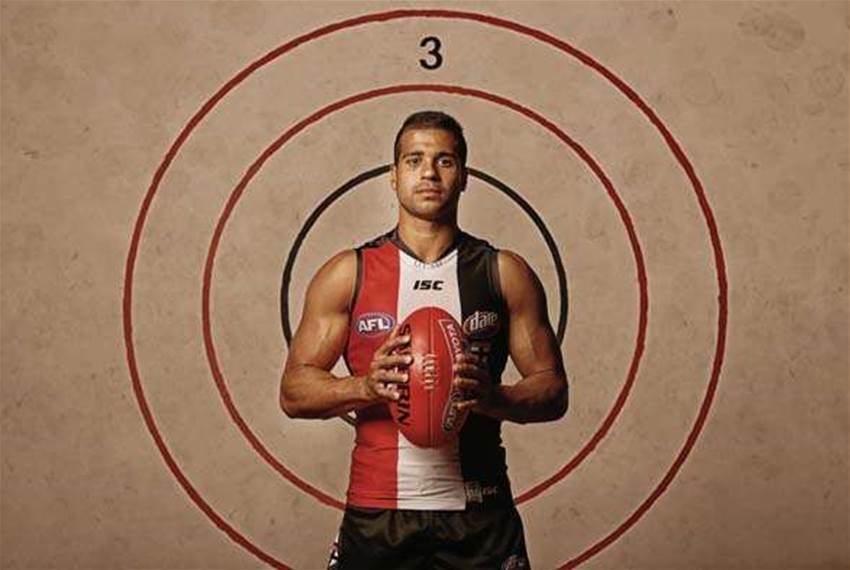

To watch him run onto the field at Moorabbin to train with his team after his ban is gratifying. Four days before when he received his jumper, the St Kilda faithful, understanding its full implications, gave Ahmed a loud, sustained cheer that drowned out the piercing din of the Melbourne Grand Prix less than a kilometre away. He’s comfortable now. “At first I thought my name was tarnished, and for my family and myself I didn’t like it, but I think the public understands.”

He comes back to the game not full of revenge, but the desire for personal vindication; to prove to his family that his only wish was to make them proud. He comes back 25 and undeterred.

“Age-wise, I’m old. But in footy terms I’m still pretty young. I feel I’ve come back a better person, and I want to be a better player, definitely, and a great team member. I’d like to be a one-team player. This club has shown great faith in me twice now.”

Ahmed Saad ran out to train with his friends with visible joy, immersing himself happily in swirls and eddies of red, black and white.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open