Tennis’ three “innovators” might not have invented the sport, but they certainly pioneered the game we know today.

Tennis’ three “innovators” might not have invented the sport, but they certainly pioneered the game we know today.

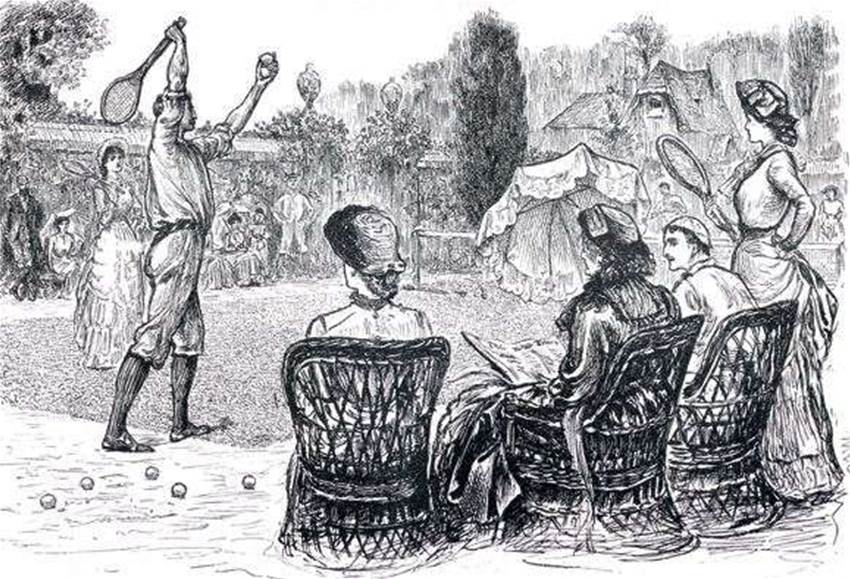

Sketch: Getty Images

Sketch: Getty Images

Games that involve hitting things (most of which evolved into the spherical objects we now know as balls) with sticks (which turned into bats, racquets, clubs and, er, sticks) have been around since human beings decided they needed amusing diversions in between stints of belting animals with the same objects. No one knows when the earliest tennis players first appeared, but it is known they probably had French accents. They derived their game from pastimes played even earlier by people with Ancient Greek accents, as recorded by Homer. We know, too, that it went indoors after it migrated to Europe’s colder climes. Both Shakespeare and Chaucer make mention of the indoor game, vestiges of which remain today.

As is the case with Dick Cavill in swimming, or the development of table tennis, archery or soccer, there are times when the sport’s greatest innovators, rather than bringing it into existence, facilitated its transformation into a popular sport that stood the test of time.This was the role of Major Thomas Henry Gem, Augurio Perera and Major Walter Clopton Wingfield. It is often, wrongly, believed that Wingfield invented the modern game. But the men who can lay the strongest claim to that were Gem and his friend, Perera. They, in fact, took the game back outdoors after becoming frustrated at the expensive facilities and complex equipment associated with the game of “rackets”, which they played at the ancient Bath Row Racquets Club.

At his property called Fairlawn, Perera had a croquet lawn that, oxymoronically, saw very little croquet action. The ethnic backgrounds of Gem and Perera contributed to the rules of their new game. It had elements of “rackets” and the Basque game of pelota. They marked out the first rectangular court, close to the dimensions of today’s version.Their game was being played by others, in fact, by 1859 – a few years before Major Walter C. Wingfield came up with his variation, which sported the name sphairistike. He thought it was a catchy moniker. Indeed, i might have been, but for its unpronouncability. Wingfield’s version was also played on an hourglass-shaped court – another masterstroke that might’ve stood the test of time if it wasn’t for the fact it didn’t. But the Major pressed on.Wingfield was to tennis what John Jaques was to table tennis: an entrepreneur who saw a quid in the game. Sphairistike was, to his perpetual puzzlement, not doing so well. His friend Walter Long suggested that another name was needed if it was to catch on. Another friend, Arthur Balfour, suggested lawn tennis. The derivation of the name has many possibilities, ranging from the French tenez, “pay heed” (which players called to opponents before serving) to the Egyptian town of Tanis, which manufactured linen that the earliest balls were made from (see also the German tanz – to dance).Though his “portable”, hourglass court didn’t catch on, the name did, as did his oval-shaped racquet. It’s believed Wingfield also borrowed much of the French vocab for the new game, which is still used.In February 1874 he patented his new game, codified its rules and sold it to public in sets consisting of his portable court, rubber balls, four rackets and a net. Serendipitously, around this time, Charles Goodyear developed vulcanized rubber and suddenly it was possible for a ball to be soft and bouncy – perfect for grass surfaces. Very soon it became England’s most fashionable pastime.

As the game evolved, and croquet lawns all over the better parts of the British Isles came vigorously alive with new sights and sounds, the game of croquet itself was hardest hit. In 1876 (some might call this a leveraging masterstroke), the All-England Croquet Club at Wimbledon conceded that they needed to add facilities for the new game, and the next year they sponsored the first All-England Championship ‒ the first Wimbledon. It proved so popular, it immediately led to further debate about standardising the rules.

Then, in 1874, American Mary Ewing Outerbridge met Wingfield in Bermuda, returned to the Staten Island Cricket Club in New York and in another masterstroke (this time of prescience – cricket never did catch on over there) laid down a tennis court. By 1880 the first American National tournament was played there – the beginnings of the US Open. Club tennis had already begun in Melbourne, Australia in 1878 and the MCC was responsible for the first Australian tournament, also in 1880.Gem and Perera’s first-ever grass tennis court has long since been ploughed in, but a plaque on the gates at Fairlawn proclaims the birthplace of one of the few sports that can claim the title of a world game.

‒ Robert Drane

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open