His move to the Swans wasn't as apocalyptic as everyone thought it would be. Maybe ...

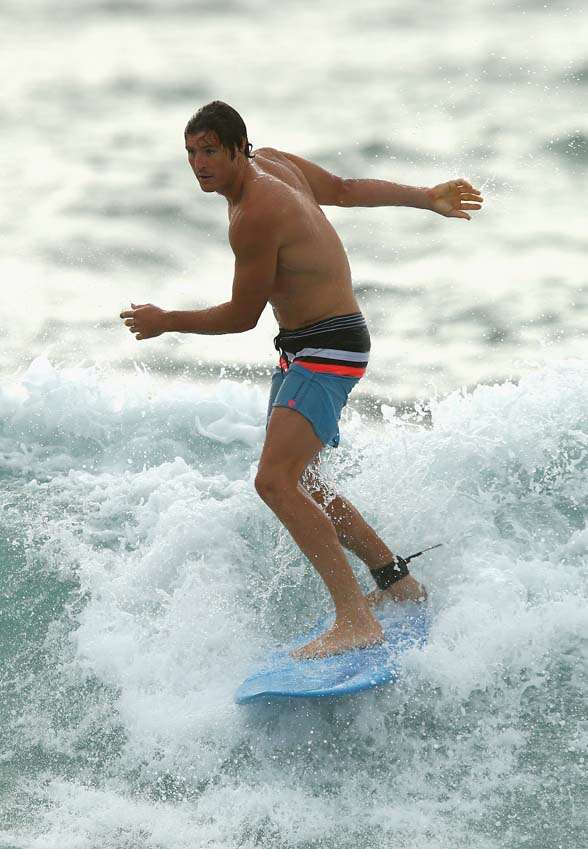

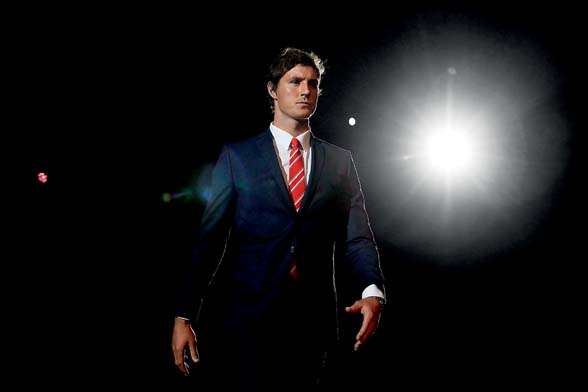

Kurt Tippett is in a reflective mood. He’s just completed an Anzac Day-related photo shoot at the North Bondi RSL, so it’s no surprise that his frame of mind is inclined to the appreciative. He looks out upon the Bondi vista, his neighbourhood for the last three years, and proclaims his thanks for his career lot. “It’s a great place to live,” he says, before checking himself with a grin. Sydney’s great April storm of 2015 rages outside, churning the surf into pure white froth and relocating the beach sand all over the Esplanade. “Not so much today,” Tippett concedes. “You get it most weeks.”

Irony, yeah. Or metaphor? The 28-year-old’s tenure in the Harbour City can be characterised as a dream setting that’s had to endure some inclement conditions. Tippett arrived at the Swans amid an atmosphere that was snarky, vindictive and over-the-top. He was marked out at the time as the exemplar of What Was Wrong With Modern Footballers. He ran counter to the game’s established culture, and stoked a whole lot of southern-state resentment along the way. While the two-and-a-bit seasons since have cooled matters somewhat, at least around Kurt Tippett, the basis of such angry hype still lingers, ready to turn to a howl at short notice.

The Swans have had a good start to the season, much better compared to the false steps out of the gate last year, and Tippett has been around to enjoy it. The big talking point this particular week in Swans’ circles is Isaac Heeney. The rookie teen just had a breakout game, booting four goals and authoring one of the sure-fire highlights of the season when he put his body on the line – the line quite literally being the goalpost – to score one of them. Heeney secured a Rising Star nomination, not altogether unexpected for a first-round draft pick who looks every inch a promising player, and with his blond hair, a cinch to be a prolific Brownlow vote-getter in future.

Nothing too unusual there. But the thing about Heeney that has lit up the AFL news cycle is his pedigree – Heeney is a product of the Swans academy program, and potentially shapes as the first out-and-out star to emerge from the junior development system. These northern state academies – GWS, Brisbane and the Gold Coast also each have one – are a particular sore point for the rest of the clubs, who suspected yet another instance of the AFL putting its thumb on the scale in favour of its expansionist vision. The parent clubs have priority access to their academy juniors through the draft, which is how Heeney, rated as a top-three prospect in the pool, landed at the Swans at pick no.18. The objections followed, led by Eddie McGuire (big shock, that one), and the draft’s bidding system will go in for more tweaks.

The Swans’ rebuttal was perfectly reasonable: they had invested the resources in Heeney, a Newcastle kid who admitted he would be playing rugby league if it hadn’t been for the avenue that the academy provided when he was 12 years old. This is how the academies were meant to work, leveraging the club brand to get more boots on the ground in non-traditional Aussie rules territory. The problem: the academies are yet to produce AFL players in great number (only 17 NSW players have been picked over ten years), but are already minting star-level talents capable of tilting the draft.

This debate has a familiar-sounding relevance to Kurt Tippett. Raised on the Gold Coast, he didn’t exactly envision a future of AFL stardom. In some respects, he fell into the game. “Growing up, there’s a lot of opportunities to play a wide range of sports: cricket, soccer, rugby, there’s a lot of swimming that goes on, surf lifesaving, surfing. So the kids have a wide range of opportunities to play.

“Guys like myself, my brother, Isaac, and other guys out of the northern regions, we’re learning a lot of skills. For the academy to be there, for kids to experience the AFL environment, it’s very important. That pathway becomes clear, and it’s a big step in getting guys to continue playing AFL.”

Truly, Tippett represents the kind of physical talent that the modern AFL is voraciously seeking. He played everything as a kid: rugby at school, a stint as a surf lifesaver, and his best sport, basketball, which he played for Queensland at the state junior level. Some of his peers at the national championships turned out to be pretty fair: the ACT’s Patty Mills and Joe Ingles of South Australia, both future NBA pros, while Victorian Scott Pendlebury would eventually become an opponent on another stage.

Tippett’s home environment was also highly conducive to athletic development. The bloodlines are evident: brother Joel plays in the AFL for North Melbourne, while sister Gretel has played basketball for the AIS and Logan Thunder in the WNBL before switching to netball for the Queensland Firebirds. “My family is responsible for my love of sport,” he says. “My parents were very active, they were from country NSW. Ever since I can remember, we were always outside playing sport.

“Then, having a brother so close in age. We are only 17 months apart. He’s the perfect training partner, and we’re super-competitive kids. We were out in the yard, playing and competing and enjoying that. Then my little sister came along and we treated her like another younger brother, really. She became one of the boys pretty quick. She’d compete with us and our friends.”

Tippett started footy on a lark. Some year-12 mates from school, All Saints Anglican in Southport, needed numbers for a quick-game comp. Tippett was one among the numbers, but it was a number that was seen, as he found himself with an offer to play for the Southport Sharks club. After returning from a basketball tour of the United States, where he mulled the possibility of playing college hoops, Tippett instead committed to footy.

“I played both sports for a while, tried to juggle them. You want to be involved in everything, at times to our detriment,” he laughs. “I was fortunate to have some great people around the Southport Football Club.” One of his school friends was Ben Merrett, son of Bombers and Bears great Roger, who Tippett credited with teaching him concepts of the big-man game. Brisbane premiership player Shaun Hart was also around to kick the footy with, while Norm Dare, an institution in Queensland football, was his senior coach at Southport.

“It was a timing issue for me – I was just so fortunate. That environment kept me so eager to learn and to develop. I was able to see the steps I was taking because I was around these sort of guys, and it fuelled my passion to keep going with the sport.”

From his first taste of football in 2004, Tippett found himself in the AFL Draft pool two years later. In a conspicuously talented 2006 class – Selwood, Boak, Riewoldt, Hawkins – the kid from the Gold Coast was picked in the second round, the 32nd overall selection, and was headed to Adelaide.

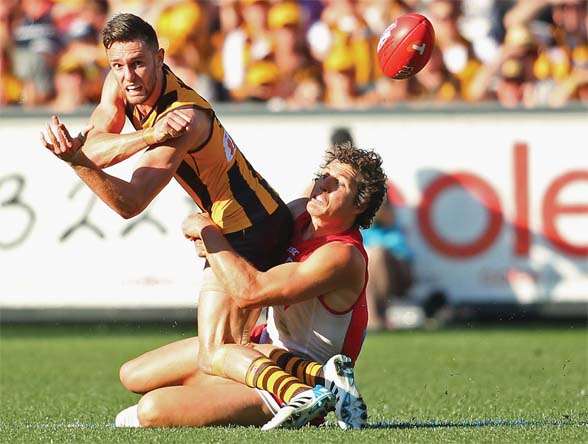

The manner of Kurt Tippett’s exit from the City of Churches obscured all the detail that came before it. Over five seasons with the Adelaide Crows, he played 104 matches, kicked 188 goals, and was part of a revitalised playing group that took Hawthorn right to the edge in their 2012 prelim final; only one straight kick short of an epic upset. Tippett had been among the best on ground that day, leading the Crows’ charge and outperforming the Hawks’ star spearhead, Buddy Franklin, who had one of his periodic bouts of waywardness in front of goal.

Hawthorn, solid favourites for the flag, went on to lose to Sydney. It was a tense decider, but proved no match for the intrigues of the ensuing offseason. And at the centre of it all was Kurt Tippett.

In a league that has accustomed itself to the drip-fed detail of the Essendon saga the past few years, the Tippett affair now appears quaint. Some facts are in dispute, but in broad outline, the Crows had tried to keep their young star from bolting back to Queensland after the 2009 season by making him their highest-paid player, but also with the promise of bonus third-party money and a trade guarantee at the end of the three-year contract – both violations of the AFL’s salary cap and draft-tampering rules. Whichever side was responsible for coming up with the particulars of the deal, they all came out of it looking bad: the Crows for covering up the breaches, Tippett for either agreeing to or being unaware of them.

The controversy had bubbled, but turned to steam in the trade period when Tippett nominated the team he wanted to go to. Rather than return home to the still-fledgling Gold Coast Suns, or similarly become a building block at the GWS Giants, he wanted to go to the Swans. The tailoring for his black hat was complete – for rival fans, he was seen as a guy who had quit on his team-mates (by text message, no less), was complicit in rules violations, had ganged up with an already strong team and was still able to score his $3.55m payday. The fact that the reigning premiers could afford him, with their cost-of-living assist, was even more galling.

Tippett remains reluctant to talk about his departure from Adelaide. The matter is past, and having served an 11-game suspension that wiped out the first half of the 2013 season, he’s served the time. He’s at pains to note that his experience in Adelaide was a positive one, contrary to claims that he didn’t like the town. The footy fishbowl in South Australia took some adjustment, especially coming from the relaxed GC, but as the on-field results showed, Tippett handled it.

“I lapped it up,” he says. “It’s not an easy transition, because there’s so much that’s unfamiliar to you. I had never been to Adelaide before. But you come into a football club where a lot of other guys are in a similar position, you make great friendships, and training alongside guys like Mark Ricciuto, Andrew McLeod, Simon Goodwin, Nathan Bassett, legends. I remember the first training session being pretty daunting, but you get to learn.

“For the guys from the northern states, there’s a high possibility you won’t be playing at home. I remember being 18, I’d do anything for an opportunity to play at the highest level. While moving is a big step, it’s also a step you’re thrilled about. As a young kid, that’s all you can ask for. I’m very grateful that Adelaide gave me that opportunity.”

It was Tippett’s fate that his employment status was entwined with the advent of a new era in the AFL. The 2012 offseason was also the first for free agency, and Tippett’s situation played out against the backdrop of one-club stalwarts jumping into new and unfamiliar guernseys. Footballers had changed teams before, but the sight of veteran players making the switch, having become so associated with a club over at least eight years, was particularly jarring. To many a fan, raised on the faith of loyalty to club, this was another signpost on modern footy’s road to hell.

Contemporary AFL fandom rests on a delicate compact – the ever more nationalised and professionalised comp has drawn together its various constituencies and reached out to new ones, but it also trades heavily on its supporters’ fealty and nostalgia for footy as it was. The notion that a player would show such disregard to the club that brought him along is hard to accept. Until, of course, one accounts for the fact that said player might have come from the other side of the country, from outside a football culture or plucked from another sport entirely, and deprived of the choice (at least initially) of where he wants to play. The embodiment of this tension is how elaborate the father-son rule has become – a sentimental consideration straining against the cold, hard reality of the market for AFL talent.

Perhaps it’s the ubiquity of fantasy football, but player movement has the capacity these days for inciting the kind of wild-eyed spirit once reserved for on-field biff or, you know, the actual results of the games. Rather than a sober appreciation of how a guy might fit into a different side, or the influence one player has among 18, every trade, pick or signing is treated as the key to unlocking the destiny of the season. It’s the fantasy football we play in our heads, where fans are engaged in a strange game of expectations management and short-term over-reaction.

“We saw guys like Gary Ablett go to the Gold Coast, there’s been a lot of other players shifting club whether it be for opportunity or to put themselves in a particular environment,” Tippett says. “Every player has got their reasons for it.

“The game is in a bit of transition. We saw the introduction of free agency and I think, since then, the amount of player movement has been greater every year. Like other sports around the world, it will probably continue to increase. There’s been talk of a midseason draft, these sorts of things. I think it’s interesting and exciting ... It keeps people talking about our game.”

Did he think that the reaction to his move would have been less intense had he chosen a team other than the Swans? Tippett offers a rueful laugh: “Possibly; that’s hard to answer. Sydney had won the grand final at the time, so to come into a grand final-winning side was something I had never pictured or thought about. But it was a fantastic opportunity, and as an athlete, you always want to be successful ... Hopefully, I wanted to add to that.”

******

There’s another thing about the fantasy football going on in our heads – often times, it doesn’t quite pan out. Sydney’s signing of Kurt Tippett didn’t bring on Armageddon; if anything, it was subsumed the next offseason when Buddy Franklin brought his even bigger name to town.

“He is an object of fascination,” Tippett says of his team-mate. “When he signed up to the club, I didn’t know him; I’d played against him a couple of times. Getting to meet him, seeing the interest that he brings – that was new to me. You go down to Bondi for a swim with Buddy and there are cameras there. People love to know what he’s up to.

“He’s got charisma; he’s a hugely talented football player, that’s where it all starts. He’s got a great footy mind, great team player. He performs at such a high level; he trains at that level. He’s doing the sorts of things you see on the weekends at training. Learning from him has been unreal for me. And seeing some of the stuff he does, I feel I’ve got the best seat in the house.”

It’s not only Buddy. “Being surrounded by all the guys in the club is motivation. You’ve got Adam Goodes sitting there; everyone knows how much he’s achieved in football, and then outside of it. You’ve got great leaders in Jarrad McVeigh and Kieren Jack, guys like Josh Kennedy. They’re all huge motivating players for me, to play alongside these guys. Help them, and they obviously help you.”

While the Swans injected shots of star power into their vaunted Bloods culture, it has yet to result in another premiership. Last year, they appeared to be on course, rebounding from three losses in the first four rounds to another September date with Hawthorn. But in an inversion of their 2012 meeting, it was the Hawks that exuded toughness while Sydney was curiously flat, and what was expected to be a close contest turned into a blowout rarely seen in grand finals in recent times.

Tippett did not have a good game; in a ten-goal hammering, few players on the losing side do. While it would seem the defeated in a grand final should be allowed to slink away, there are post-match functions to attend. “Couldn’t have ever imagined it, to be honest, until I went through that,” Tippett recalls of the event. “You have your family and friends there, people who have supported you through your career and the season. To feel the way you did, it wasn’t a great experience. Saying that, we’d had the support of a lot of people, so it’s an opportunity to thank people for their efforts.

“It was a totally uncomfortable feeling. There were a lot of uncomfortable conversations. The boys were bitterly disappointed. There was a lot of emotion in the room from everyone involved, because everyone’s so invested in the season. So it’s an uncomfortable night.”

If there was any consolation to such a loss, the Swans had won more games than in any other season in the club’s history, and would be in a position to contend going forward. Absorbing Tippett and Franklin into the payroll had cost Sydney some experienced performers and sapped the list of some depth over the past couple of years, but the club was ready to count on a younger set coming through.

The most tantalising prospect, though, is what a healthy Kurt Tippett could do. He has played no more than 14 games in either of his first two seasons with the Swans, with the first one ending in injury and the second one starting with one. While he continues to manage a tendonitis issue in his knee and was kept out of preseason matches, Tippett says he’s as healthy as he’s been in his time at Sydney.

“Consistency, being able to consistently train and play, is my short-term goal. I’ve been able to enjoy it to an extent this season. I had a really good preseason, missed a bit of footy in the NAB Cup. But I’ve been all right to train and play so far ... I feel fantastic physically. In terms of match play, I’ve still got improvement left in me. Like every year, you’ve got to build the season. That’s what I’m about this year.”

The rest of the league’s horror vision – a fully armed and operational combination of Tippett with Buddy – might yet be seen. In an age where each team hoards a single key-position tall like a precious gem, the thought of having two is fearsome, with each tacking off each other from inside the forward 50 to around the ground, or in the ruck in Tippett’s case. The general impact such athletic big men can have on the game can’t be overstated.

“In coming to the Swans, in discussion with coaches, that has always been the vision for my role – to play a bit of both, depending on the opposition and our team make-up,” Tippett says. “To be able to settle into that now is good, and I’m enjoying playing both roles.”

For Tippett, it would come as something of a relief that the questions he deals with now have to do only with football. The way is clear for him to just play, and where he falls on the scale of footy heroism or villainy will be no concern of his. “As an athlete, you’re always looking to put yourself in an environment where you believe you’ll get the most out of yourself,” he says. “I guess that’s different for everybody, but I truly believe Sydney is the place for me to get the most out of myself.”

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open