Can the stats men really tell us what actually happens on the field during an AFL game?

By Jeff Centenera

PROLOGUE

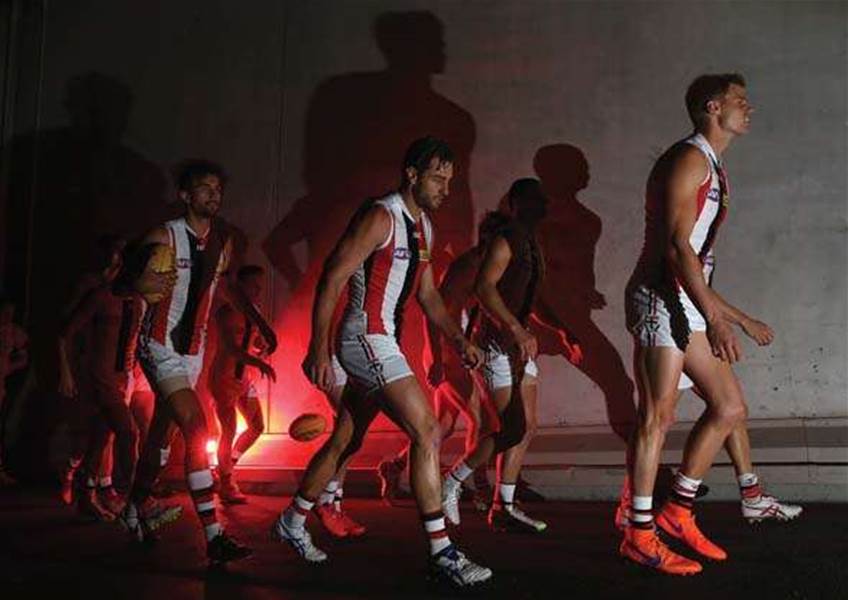

It would be hard to convince a Western Bulldogs or a St Kilda supporter that things even out in the long run. We're talking about two fan bases that know what it means to be "long-suffering", two clubs that share premiership droughts verging on a-flag-before-I-die levels. Whenever these teams meet, as they did in round six of this AFL season, there's no great sense that the fates are in either's favour.

The Bulldogs had emerged as the darlings of the early campaign, defying offseason turmoil that cost them their coach and captain, to win four of their first five. New coach Luke Beveridge, who incidentally had been headed to St Kilda's staff before landing the Dogs' appointment, had his team playing a brand of in-your-face footy that was irresistibly fun to watch. Meanwhile, the Saints had only a solitary win over lowly Gold Coast. St Kilda had been the preseason betting favourites for the wooden spoon, and had lived up to the profile of a young outfit with low expectations: close losses and blowouts in equal measure, but defeats all the same.

In a conventional AFL narrative, the Bulldogs were warm favourites. They were nominally the home team for the game against the Saints, but both teams play the large share of their matches at Etihad Stadium. St Kilda's veteran stars, Nick Riewoldt and Lee Montagna, were returning after multi-week layoffs. At the typical odds circulating pre-game, the Dogs were considered a 78 percent chance to win. Another way of saying that, if they played four times, they should win three.

FIRST QUARTER

19.23 on the clock St Kilda scores first. A lateral mistake on the Bulldogs' defensive 50 leads to a turnover, and three handballs later, Jack Steven has a set shot ... and hits the post.

Encoded into Australian football is a fundamental disparity - if Steven's shot is just a little right, he scores six times the points. Accuracy, or lack thereof, can render moot so much of what happens on the field. But here's the thing: goal-kicking, which generally ranges between 48 and 55 percent, is a volatile phenomenon. Even a sharp-shooting bunch of kicks can't depend on being accurate any given week.

14.28 The Bulldogs are ahead with the first goal on the board, but their teen giant Tom Boyd misses from about 20m, right in front. Less than a minute later, he does it again. Itís a moment that seems like it could be important. Then not. Then maybe hugely important again.

Anyhow, his team has been dominant so far. Their tackling borders on visceral, and it creates a huge advantage in territory. This shows up in the inside-50s, a simple measure of how often a team enters the ball into their forward area and one of the most widely invoked numbers in any AFL coverage these days. Winning teams pile up inside-50s; the top three in the stat last season all made the preliminary finals.

Curiously, the number of tackles a side makes, traditionally regarded by coaches such as Allan Jeans as a mark of vigour, has no correlation. "I don't even bother with tackles," says Ted Hopkins, with a chuckle, noting that clearances don't matter much, either. Carlton's comet of the 1970 grand final, founder of Champion Data and now head of data analysis firm TedSport, Hopkins was a pioneer in the quest to understand football by numbers. He gave definition to many of the stats, coining terms such as "hard-ball get" and "clanger".

While his framework largely endures - it even entertains the thousands engaged in fantasy footy - it doesn't satisfactorily explain what's going on.

There are plenty of obvious, discrete things to count during an AFL game, and possession-minded modern football has accentuated this. Even in a sport that appears chaotic, Hopkins can boil it down to a single, stat-based principle: the effectiveness of field kicking. "Because the kick is so valuable - you can't score a goal with a handball - the ball travels quicker and longer by foot," he says. "You've got to gain territory and position, and the best way to do that is by foot. The handball comes in because there is so much pressure to stop the player kicking to advantage. That's it."

Hopkins' work at TedSport has been to better measure quality use of the ball, as well as account for how pressure from other opponents affects it. This builds on an early key insight of the stats revolution in the mid-to-late 1990s, when Hopkins asked a mathematician to crunch some numbers and find the causes of defeat, excluding accuracy at goal. "The single-most factor that loses a game of football is crappy disposal in the backline. It was evident then, and ever since," he says, noting how AFL teams across half-back are these days lined with classy skill players rather than punch-from-behind types. "I used to argue with coaches: if you've got a crappy kick and you want to put him in the team, put him in the forward pocket."

8.39 As it would happen, a tackle by the Dogs' splendidly named Marcus Bontempelli, who had set up their first goal, creates a Saints turnover and leads to the Bulldogs' second goal, from fellow young gun Jake Stringer.

4.20 Riewoldt receives an innocuous 50m penalty on the far wing, then kicks the Saints' first goal. After another goal with less than a minute left, St Kilda trails by seven.

It's a flattering deficit. As the other stats tell it, the Bulldogs already had 20 inside-50s to the Saints' nine. Some 71 percent of the quarter had been played in the Dogs' half, but they led by little more than a goal. Despite their impressive play, it was still a contest. But to think about it in terms of probability, the Western Bulldogs were 80.6 percent likely to win from this point - a slight improvement from the start of the game.

SECOND QUARTER

18.33 Luke Dahlhaus, completely out of Saints' defender Sam Fisher's field of vision, lays on a surprise tackle in the goal square, then goals. The Dogs, with a 13-point lead, edge up to an 85.5 percent chance.

The percentages quoted here come from a model created by Tony Corke, who runs the Matter of Stats website, part of the burgeoning online community bringing advanced stats to the AFL. Corke is a Sydney-based data scientist who quit following rugby league and started watching AFL because he found league too formulaic. His model estimates a team's chances based on the lead or deficit, and the time remaining in the game. "It kind of reminds me of Duckworth-Lewis in cricket," Corke says; where the rain-delay formula is based on the "resources" of wickets in hand and balls remaining, "resources" in football relate to the score and time.

"The key finding is how quickly these percentages change," Corke says. "Our intuition is that a single goal in Australian rules can't make much of a difference, but the stats say otherwise."

To think a team thatís two goals up after a quarter is already an 85 percent favourite defies common notions of how games can turn. But this is an example of what the psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls the struggle with thinking statistically. It's a bias of our minds that we latch onto the comebacks that occur. "You remember the one time that it happened, and forget the 57 times it doesn't, or it turns into a blowout or fail in their comeback," Corke says. "Any lead at all in the third term is a fantastic lead. I had a look at the stats: 98 percent of teams that had a three-goal lead at three-quarter-time went on to win."

Jake Sringer's speccy attempt was impressive, but made no mark on the stat sheet. (Photo by Getty Images)

Jake Sringer's speccy attempt was impressive, but made no mark on the stat sheet. (Photo by Getty Images)15.45 Stewart Crameri boots a beauty, wheeling off a step inside the 50m arc. Dogs up 19. Win probability: 89.6 percent.

12.54 Crameri gets another major after a string of eight disposals. Margin is 24, win prob up to 92.4 percent.

6.38 St Kilda's prolific on-baller, David Armitage, has racked up touches, but disposal no.20 hands the pill over. Things are decidedly going the Bulldogs' way, and Liam Picken kicks the kind of sharp-angle goal that confirms it. Lead is 36, their chances now 97.1 percent.

0.00 On the half-time siren, Picken marks and scores from a set shot, pushing the lead to 49 points. Bulldogs 99.4 percent to win.

Everyone in the building, aware of the percentages or not, understands the probable outcomes from here. But a pair of incidents right on half-time, which have no reflection in the score, change the tone. Just before the ball fell to Picken, team-mate Clay Smith had buckled at the front of the play. He'd suffered a knee injury, devastating at any time, but more so to the Bulldogs, as this was the third time that Smith had hurt his ACL.

Smith had to be taken off on a stretcher, creating a short delay before Picken's shot. A minor flare-up between Stringer and Riewoldt prompted an all-in, with bodies coming from all directions, although there was no serious altercation. It gave the fans a reason to get fired up, and capped a weird emotional sequence: the sobering cruelty of Smith's injury, to the elation/deflation of the imposing margin, to the old-school rush of blood from the boys. They are the kinds of things that people remember matches for.

Unlike in the first quarter, when their dominance wasn't reflected on the scoreboard, the Bulldogs had extracted full value from the second stanza. Seven goals to none, 20 inside-50s to eight, disposal efficiencies that hit 80 percent, while the Saints couldnít muster a single effective disposal. The 49-point gap represented a historic chasm - only 15 times in the VFL/AFL had a lead that large been overcome.

THIRD QUARTER

17.51 Stringer nails one, a step inside 50, the kind of goal that says "we can't lose". Lead is 55. The biggest margin overcome in AFL/VFL history is the 69 points that Essendon pulled back against North Melbourne in 2001, an up-and-back shoot-out that produced 330 points in total for the match. St Kilda, perhaps befitting for a team named after figures you pray to, have been involved in three of the five biggest comebacks, including a 55-point rally way back in 1937. But in discussion of the gameís best comebacks, few would go past the iconic 1970 grand final. Carlton came from 44 down to beat rival Collingwood in front of a crowd of 121,696, a contest of free-flowing action that has been called the wellspring of the modern style of Australian rules.

Hopkins famously came off the bench at half-time to boot four and help spur the comeback; perhaps just as famously, he only played one more senior match afterward, before embarking on his other career path in the game. He's reviewed past matches such as the '70 GF through the statistical lens, and while numbers can lie, they can also demystify. Legend had it that the match turned when an unusually calm Carlton coach Ron Barassi urged his charges to handball and get the game moving.

"The 1970 grand final is a classic of two different types of system applied in the first and second half," Hopkins says. "The famous handballing - in the second half, Carlton in the back 50 had four handballs, right? And each one of them went to a Collingwood advantage. I think Carlton had 44 handballs for the game. But the myth has grown that handballs turned the game."

The nostalgic glow of a great game hasnít influenced Hopkins' view about why things happen as they do in football. "The beauty of AFL is the randomness of the scoring. Generally, that's the reason the length of the game is important - all the bits and pieces of variation and chance, the talented team, or the underdog, has a good chance of coming back."

16.35 On the kickout, Dogs' captain Bob Murphy keeps it, only to be tackled by Saints ruckman Tom Hickey. From Murphy's embarrassing free-kick giveaway, Hickey records his teamí's first goal for a quarter. Ninety seconds later, the Saints get another from Armitage. They're still down 42.

13.42 Having just missed on a poster-perfect speccy, Stringer's snap sails wide for a behind.

11.41 Saints tyro Jack Billings, a left-footer, kicks a terrific goal from a tight spot in the right forward pocket, a goal as impressive as Stringer's.

6.06 After three turnovers from the Bulldogs trying to exit their defensive 50, a high tackle on Saint Jack Lonie leads to another goal.

2.11 An Armitage kick flies to the back of the pack, eluding the players properly waiting front and square, and leads to a goal for yet another of the Saints' collection of Jacks, Sinclair. After Josh Bruce adds one before quarter's end, they've kicked seven without answer, and cut the lead to 12.

By anyone's view, momentum had dramatically swung in St Kilda's favour. That is, unless you take the statistical view, which means you view the entire concept of "momentum" with scepticism. In any set of random data, such as the distribution of goals, there will be runs that look like patterns. Corke brings up an old stats class experiment where the teacher gets a group of students to flip a coin 100 times, and a group to make up a bunch of coin flips. The teacher can always pick the made-up one. "That's because people don't make up runs of four or five or six heads or tails in a row," Corke says. "It's the same thing. We see four or five goals, and we think momentum. Not really, it's just a streak."

Corke concedes there may have been a momentum effect in Bulldogs-Saints. "In a typical game, you get 25 goals or so. It's very difficult to rule out chance with such a small sample." Ultimately, momentum is sport's answer to the placebo effect. If athletes believe in it, it might be real.

FOURTH QUARTER

18.42 A Boyd set shot from about 50m falls short, but Dogs' ruckman Ayce Cordy marks on the line and goals.

St Kilda's seven-goal stretch had reduced the Bulldogs' chances to 85.4 percent, but kicking the first of the last propped them back to 92.6 percent. When they kick another less than a minute later, they're back to 97 percent. The Saints' rally appears noble but fruitless.

15.20 With two defenders tied up in a contest with Saints' spearhead Bruce, Billings crumbs and snaps through a goal. A minute later, he has a running shot into a waiting goal, yet misses badly.

Ask an analytics-inclined thinker in any sport, and they'll admit to two mysteries that their numbers can't entirely account for yet. One is injury, although the GPS trackers of the world are trying to change that; the other is talent. Smart teams can run the numbers and try to tilt the odds for success. But it's still the right players who will execute the plan, or upset the other team's.

The 19-year-old Billings was the third pick in the 2013 Draft, and has the look (and the Saints' hopes) of a future star. He has the kind of clean foot skills that have become the most prized commodity to player development types, able to extract that bit of added value from his disposals across the field. So far this season, it had been Bontempelli, taken a pick later, who had earned plaudits as the AFL's kid most likely. But in this quarter, Billings exquisitely timed his moment to shine.

13.31 Saint Luke Dunstan, trying to hurry along one of those lateral moves across the backline, hits the post with his kick, recording a point for the other team. In the commentary box, Jonathan Brown brings up the classic of the form: Mal Michael's rushed behind, when he split the opponent's uprights from 30m out in a game in 2006. Dunstan's moment would be perfectly humorous if it weren't for the fact that a single point might matter as the match grows tighter. Itís a pointed reminder, pardon the pun, of how sporting outcomes turn on random occurrence. In close contests, those impacts are even greater.

Cliff Bingham, a self-described stats nerd who has written for the Making the Nut website as well as Punterís Guides books for the AFL and NRL, has a convincing perspective on the nature of close games. Looking at win-loss records over the last five years in games decided by less than six or 12 points, he found a jumble of results which Bingham also explains as the most common reason why certain teams experience dramatic moves up and down the ladder from season to season - an unusually good (or poor) set of tight results that even up over the long run.

In close contests, there's a better chance for anything to happen. Bingham cites powerful Hawthorn, which has won 75 percent of its matches over the last five years, but has won only 56 percent of its games decided by less than six, and 56 percent of matches by less than 12. The Swans, winners of 66 percent overall, have won 40 and 43 percent in those close contest categories. On the other hand, 35-percent Brisbane has won 60 percent and 55 percent of its under-six and under-12 margins.

As Bingham says, the results are not completely random - most good sides do a little better than a coin flip. "Even the best sides max out at winning about 60 percent of the genuinely close ones and verge more towards 55 percent," he wrote in an email. "Though admittedly, many of their close matches come against other good sides! "It reminds me a bit of 18-hole match-play golf. Over a full season, youíd expect the dominant golfers [read: AFL teams] to do more winning than anyone else. But if two players are all square headed to the 16th tee [read: less than a kick in it early in the fourth quarter], the 'better side' is only a little better than a coin flip chance to win from there. So while it's not completely random, it's close to being that way."

11.08 Billings, tapping into that higher footy power where the ball starts finding the player rather than the other way around, lands a bolt from the 50m number. Margin is 11, win probability for Western Bulldogs is still 88.1 percent. The anxiety level for their fans, safe to say, is significantly higher.

8.10 St Kilda goes from Jack to Jack - a set shot from Lonie falls into the hands of Sinclair on the line - who cuts the lead to less than six. Probability: 75.9 percent.

4.21 A Jack Steven free sets up Tom Hickey from 35m. The goal puts St Kilda ahead for the first time since the game's third minute. The Dogs' probability is now 51.4 percent.

3.01 Riewoldt, whose half-time switch from the forwards to the wing has proven impactful, fires a kick into an isolated two-on-two. Dog defender Easton Wood, whose slick disposal had been a feature of his teamís excellent first half, slips over. Jack Billings gathers and spears in a low, running goal. St Kilda now 86 percent to win.

At the siren, the Saints had completed the fifth-best comeback in league history. On the AFL's match centre website, the graph that tracks the margin looks like a ziggurat, rising to the Bulldogs' lead on one side, and sloping down to St Kilda's remarkable comeback. Bruce's shot after the horn tacks on a behind to set the final margin at seven.

The Bulldogs have mustered 62 inside-50s to the Saints' 47, with contested possessions basically even. Hopkins, looking at TedSport's stats, explains the Dogs had 25 "useless" inside-50s and St Kilda had 117 effective kicks to 105. "I hadn't seen the game, but I can tell you what happened because I have the data in front of me. St Kilda kept coming out of the backline and mucking up. What's happened, in my view of the data, is the Bulldogs had the ball a lot of the time because of turnovers, but they didn't punish them."

Both coaches, subjected to instant post-mortem, pledge their belief in the pendulumís swing. Says Beveridge: "There is a point where momentum goes the other way and I don't know whether you fall into a mindset where you think, 'It's going to stop eventually.' But in the end, it didn't."

Saints' Alan Richardson, speaking with near incredulity: "I didn't predict that what was going to happen in the second half was going to transpire. But what I do think it shows is this group does believe, that belief is still a little bit fragile, but is gaining momentum every time we play."

There are patterns to be seen in the randomness. The game might be remembered in the future as the breakout for Billings, or one of the last great showings of Riewoldt's sterling career. It might be remembered for Clay Smith's misfortune.

Or as a motivational tool to tell every footballer: you're never safe, or never out of it, even when the lead is 55 points.

EPILOGUE

The next week, St Kilda loses on a road trip to Adelaide. Even worse for the club's emotional state, Riewoldt suffers a terrifying head clash that requires him to be taken to hospital, and raises talk that he should consider retirement. Meanwhile, the Western Bulldogs meet undefeated Fremantle and continue to test the bounds of probability. They trail the Dockers by as much as 34 points, and the league leaders hit a win probability of 96 percent by the middle of the third quarter. But the Dogs rally, tying the game with just under ten minutes left, tilting the match to 51.5 percent in their favour. Freo steadies, kicks two more goals, and denies the Bulldogs their own unlikely comeback.

Had the Bulldogs played their three bad quarters over the course of one match rather than two, they might just have endured one big defeat. But randomness rules. Those who would argue that stats can be used to prove anything are often complaining about how much chance determines what happens. There has to be a reason for why someone wins or loses, and our minds will usually come up with a story to tell. The narratives, which definitely have their own kind of momentum, move along.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)