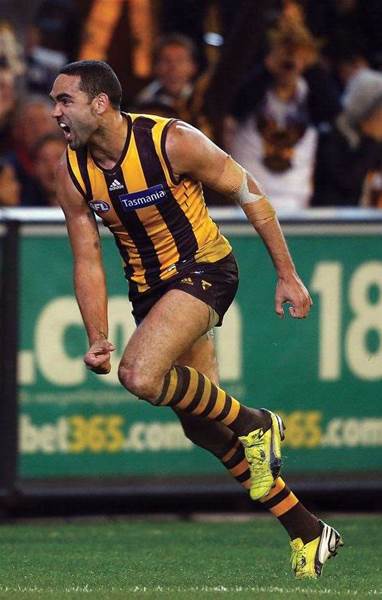

No underestimating his influence on his people and team-mates.

In 1868, the first-ever touring cricket side from Australia, the Aboriginal team, would hold “games” for the crowd’s entertainment after a day’s play. The entertainment was complimentary, but sometimes they’d collect a pound or two. In one of these games, the famous Dick-a-Dick (real name Djungadjinganook), leader of this extraordinary, well-loved and poorly paid troupe, would have opposing players and crowd members fling cricket balls at him while he casually dodged or deflected them with a shield. The crowd happily indulged, but ne’er a ball was propelled by malice, even when they threw four at a time from 15 paces!

A century later, Lionel Rose was introduced from the boxing ring by Melbourne’s Ron Casey before he’d even laced on a glove as a professional. Rose, a nervous Aboriginal kid from a family subsisting in a bush shack, mainly on bread, announced to the crowd that he wanted to be a world champion. They cheered and spontaneously threw coins. Money rained down on this reluctant ragamuffin who’d never before seen the city. The ring’s blood-stippled, sweat-streaked canvas jingled with silver. Sixpences, one and two-bob bits. Rose’s eyes lit up. He’d never experienced such vertigo in a boxing ring. All that money, all that goodwill! So much bread! There was nothing like this out at Jackson’s Track.

Almost 40 years on, at a football ground in Adelaide, money showered down upon another shy but talented Aboriginal lad. Twenty, 50-cent pieces. The currency wasn’t all that had changed. The coins weren’t lobbed onto the field, but hurled with spiteful intent, and Shaun Burgoyne had to dodge them. The verbal abuse was another matter. It was impossible to dodge.

None of these stories might be historically “typical”, but there’s no doubting the dynamic between European and Indigenous Australians had altered over all that time. It had always had its good and bad, but what might have been excused as ignorance – sometimes innocent but always harmful – had given way to a more active intolerance, festering in the inner rooms and on the porches of ill-informed bigots. Somewhere along the line this virulent strain had entered the mainstream. The captivity of Indigenous people behind walls of stereotype and caricature had been helped along by blundering governments of both stripes – even the well-meaning money they threw often missed its mark. Thoughtful strategy isn’t just about coin.

Burgoyne, of the Kokatha Mula people north of the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, had never experienced a fear like this on a football field. It demanded an order of courage he didn’t know existed. This went beyond physical confrontation with another man. Troubled, he strained to see the perpetrators in the terraces, but they “wouldn’t take ownership of their actions”. At least Dick-a-Dick was eyeballing them as they threw those balls. Burgoyne betrays no bitterness when he calls them cowards.

He takes his role as part of the first real generation of freedom-fighting Indigenous footballers as seriously as the high-profile Adam Goodes takes his. Burgoyne’s journey as an indigenous man has featured just as many nettles and ditches, road blocks and emotional shocks, but his unemotional determination to transform the relationship and somehow avoid acting the victim is typical. Any attempt to radicalise him would probably be a waste of time. Unlike Goodes, Burgoyne was assured of his identity from the outset. As an 18-year-old, he was giving motivational talks to Indigenous kids as part of a youth program. “I used to talk to them about drugs and alcohol and how important nutrition and exercise is.”

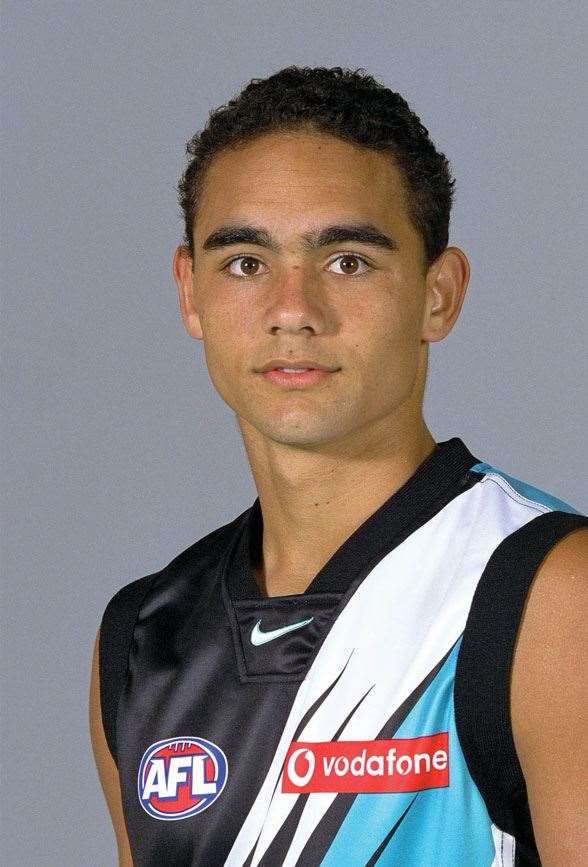

He’d come to Port Adelaide from the amazing all-indigenous Mallee Park Football Club in Port Lincoln with his brother Peter and Byron Pickett. Formed in 1980, the club has appeared in over 20 grand finals and won 11. “It’s easy,” he laughs. “If you want to win a flag, you play for Mallee Park.”

His father was a man of character, a great footballer for Port Adelaide Magpies for whom the language of his Kokatha people was his first language. Peter senior took up studies at 37, attained a degree and a Masters and became a respected administrator in the South Australian Aboriginal community. Thanks mainly to him, Shaun was steeped in his culture and understood its place and history.

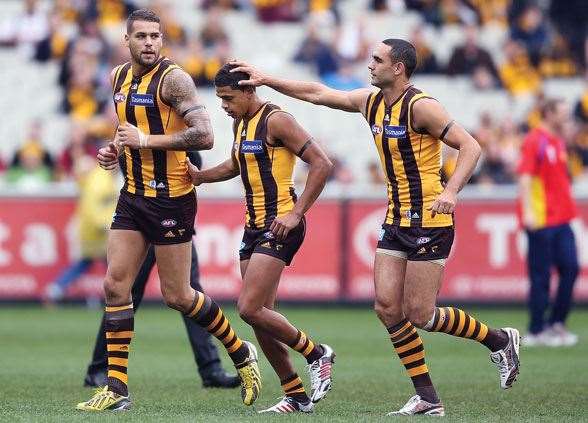

Yet he was never ostentatious about it, nor do his actions tend toward separatism. Burgoyne is as natural a weaver and mender in life as he is on the field. At Hawthorn, he does the same job Goodes has done at Sydney, showing young Indigenous players like the now-delisted Amos Frank and rookie Derick Wanganeen how to live, as a citizen and a footballer.

Burgoyne is part of a generation of successful Indigenous players who see the teaching of football club values and leadership as a way of reinforcing customs that their communities are fighting to preserve, particularly respect for elders and traditions. This inspired redefinition of what it is to come to the cities and play football, allied to the support that comes with it, has led to a dramatic increase in the quantity and quality of Indigenous participation at the elite level.

Thanks to their work, today’s players don’t need to tread the via dolorosa of past players like Gary Dhurrkay (Liam Jurrah was, sadly, a recent exception) who were plucked from the land of their people but were never quite able to shed its demands, meet all its obligations or ignore its call.

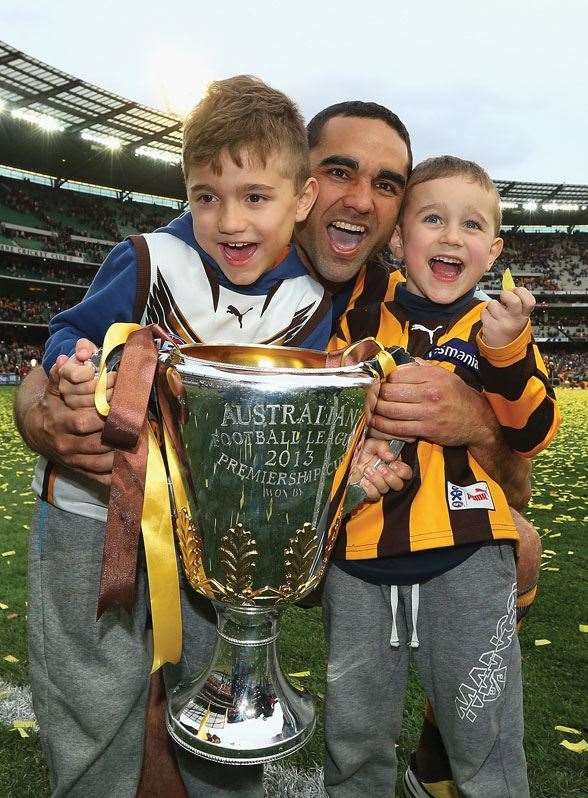

Nearing the end of a career marked by five grand finals and three premierships, Shaun Burgoyne, with that open, pleasant face a man of his disposition deserves, never seems passionate but obviously is. He’s decided to wield the sort of influence in society he exercises on the footy pitch. That is, the influence of a man who takes control yet whose deeds stay under the general radar, not because of shyness, but because of the nature of that influence.

******

In September-October 2014, Shaun Burgoyne did two significant things: he won a second premiership with Hawthorn, and he returned to Alberton, South Australia for the tenth anniversary of Port Power’s only premiership in 2004. That title and the years of near-misses that preceded it were the making of him. “There was an incredible amount of pressure on us that day, with everything that happened before, and the big crowd and it being a grand final.” He felt that pressure as he ran on to the MCG and savoured it, realising he had an appetite for it. September 25, 2004 was the day he surmounted the last ridge of uncertainty, beheld his centre and discovered, there before him, a vast calmness.

“It took me a while. I had to grow, but after that I realised pressure is something I look forward to in big games.” Since then, the ability to be truly artful in difficult circumstances has been a signature of his game, unmatched in the competition.

Port Adelaide coach Mark Williams famously walked onto the field after that win, turned to the crowd, and with fuming sarcasm theatrically garrotted himself with his own tie, signalling the end of the “choking” Port Adelaide – the team that couldn’t proceed beyond minor premierships – and at the same time lampooning his many critics.

Burgoyne became part of a grand Port tradition. Their Indigenous members during his time included brother Peter, Che Cockatoo-Collins, Gavin Wanganeen, Danyle Pearce, Byron Pickett, Chad Wingard, Graham Johncock, Daniel Motlop and Derek Murray. During his 157 games for Power, he became a player understood best by Port fans and the most au courant of commentators. By the rest, he seemed barely understood at all. To praise him to the extent he deserves would have been to reassess the way they classify footballers. The category he occupies – alone – has no descriptors, it seems, except “silky”, an adjective that forever precedes “skills” in the lexis of journalistic cliches; one to make any racially sensitive person bristle, because invariably, when used by journos, it’s a little wink meaning “he’s Aboriginal”. However, Burgoyne cheerfully insists on the nickname “Silk” – conferred by persons unknown but used frequently to describe his game by team-mates like fellow Aboriginal Cyril Rioli. Perhaps the phrase has gone full-circle and is no longer patronising. Perhaps it’s ironic. Gentle irony is part of Burgoyne’s charm, and a reason why he might one day be the best ambassador yet for Aboriginal people in sport.

******

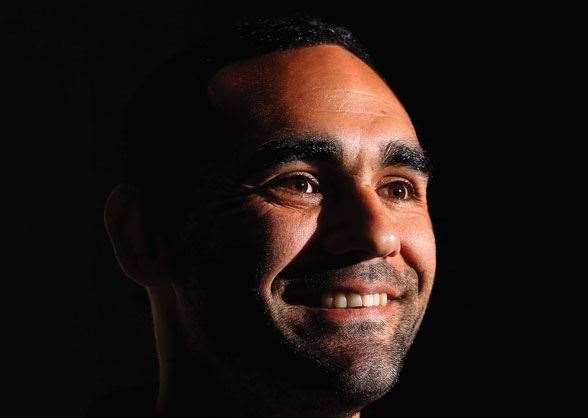

A star, whether introverted or extroverted, is declarative; a bold and visible presence. “Stardom” would destroy Burgoyne’s yeast-like influence.

Stars come and go, but there’s a level of sporting literacy that cannot be faked. You either have it or you don’t. Take Burgoyne out of Hawthorn and he’d be more conspicuous by his absence than Lance Franklin was. Franklin was a star, but Hawthorn never missed a beat after his departure. Shaun Burgoyne is a significant reason why.

But it seems he’s for the aficionado. The art-world’s idiom almost fits: he’s powerful in a diffuse way, but occasionally focussed with a sharp energy. His presence is more an immanence – felt strongly, yet lacking useful descriptors, it seems. He shapes his surrounds out there. It is hard to capture Burgoyne if you want to do him full justice. Sometimes you have to write around him rather than describe him directly, something like the “negated object” of Mallarmé, conjured in the reader’s mind by indirect words and allusions, suggestions, rather than direct description. That’s how he plays his footy often, and naturally, footy’s media and fans are into direct description of plain acts, or statistics.

Likewise, those who hand out the gongs. He’s been a challenge for even the most lucid journalists if they’ve had to justify why they feel he might be a candidate for grand honours. Shaun’s brother, Peter, was picked in the Indigenous Team of the Century. Shaun probably wasn’t considered, yet it’s debatable which of the Burgoyne boys has influenced the outcome of more games. Shaun’s list of official accolades consists of one meagre All-Australian, in 2006. Many believe he should have made the 2014 team. He probably should have made six.

In another era, another team, he’d have been Francis Bourke: quiet, capable as hell, steady always, searing sometimes, balanced and classy, never overlooked when the roll call of greats at his club – anywhere – is called out.

His assets are a reason for his lack of recognition. He has a range of talents: speed, intelligence, strength, courage, resilience, elusiveness, accuracy, intuition, a devastating finish. But his skillset has ensured he’s never kept one role. He can plug holes when many of the best players simply cannot, as goal-kicking forward, wing, midfielder or down back. His prize for such impressive versatility, sangfroid and skill is the lot of many a muted superstar: he’s a “good boy”; a trooper, a Boxer the workhorse, rarely mentioned in despatches when all-timers are kicked about.

At the same time, he’s a player the players pay homage to, like the sought-after session musician so proficient that it’s axiomatic a classic album, or song, would have been worse off for his absence. Larry Carlton. Jim Keltner. Albert Lee. A supreme practitioner. In rugby league, Manly’s Ian Martin comes to mind. The five-eighth and lock never played a rep game, yet featured in six grand finals for four premierships, and that was no coincidence. He was seriously good, his level of football nous no mere bluff. That’s why he was Bob Fulton’s favourite Manly player from his era.

******

“Stars” in their field know better than to take such men on, one-on-one. They’re no damned hood ornaments – they’re the bloody engines! If “all-time” great sides really did play games of football, blokes like Burgoyne would need to be included just to make the prodigies perform prodigiously.

Back to reality: one of the secrets of Hawthorn’s dominance is a quantum of catalytic players to ensure everyone else does their designated job with less effort. To have two such players – Burgoyne and Hodge – is an enormous blessing to Rioli, Roughead, Mitchell and their like. Without them, the stars would not be able to muster their chemistry to the same effect over a long period. With them, a team is deadly. Burgoyne has spent a career making it happen for his team, dazzlingly. Is there any more desirable skill?

******

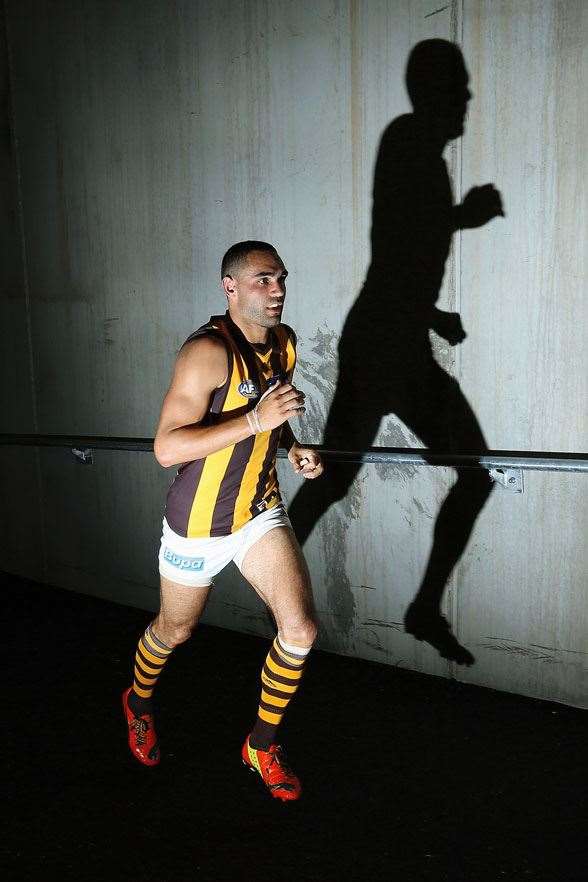

By the time he’s retired, Shaun Burgoyne’s will have been a career of almost exactly two halves. His 157 games with Port Adelaide are considered his salad days, but it’s doubtful his gifts have wilted during his 112 for the Hawks. In the last couple of seasons, he’s been in greater control of them – so much so that his measured efforts might prolong his career. Burgoyne doesn’t squander a single talent, and some of those talents seem to have accrued interest. Far from marking his decline, Burgoyne’s Hawthorn career has confirmed he’s one of the best footballers in a generation of stars.

His arrival at Hawthorn was a shock. After 2009, his brother had retired and Burgoyne, a quietly decisive man, decided he wanted to play in Victoria, where his wife hails from. His relationship with Alastair Clarkson, who’d been Mark Williams’ assistant at Port, was good, and Clarkson, a very good judge of a footballer and a list, snapped him up.

Burgoyne missed a lot of his last season at Port due to the sorts of injuries a player gets when he’s tagged heavily, and returned to play well, but it was too late. Something had changed when Peter retired. Shaun was Port’s vice-captain at the time.

He stalled upon arrival. After surgery on his knee that delayed his 2010 preparation, his jaw was broken in a game for Box Hill. When he finally debuted against Richmond in round eight, he struggled under a helmet, ran out of puff, and got 20 possessions, including a crucial last-minute mark in defence that saved the game.

After three seasons that included some remarkable one-offs, he was caught in the scattergun of criticism after bitter finishes to 2011 and 2012. Hawthorn was famously kayoed by Collingwood in the 2011 prelim final, and lost the 2012 grand final in a showcase game. While Franklin was grabbing all the attention up front, Burgoyne was derided in some quarters as the “most expensive back pocket in history”.

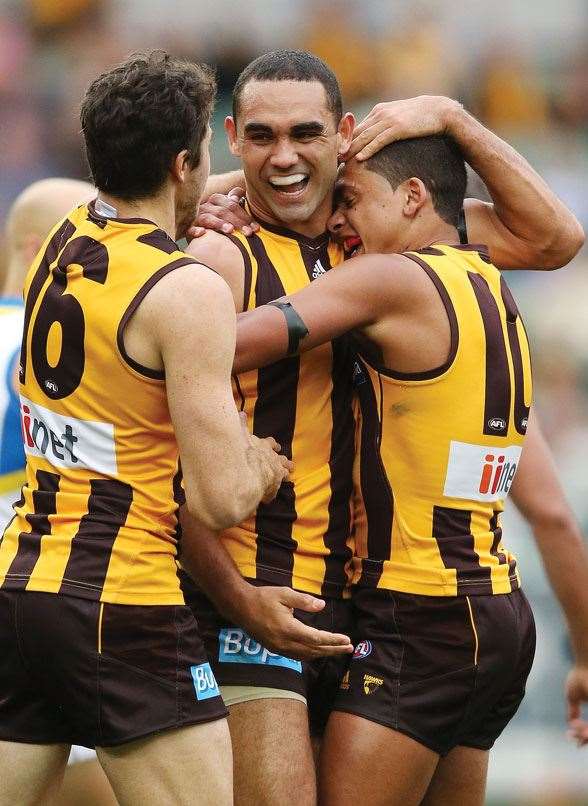

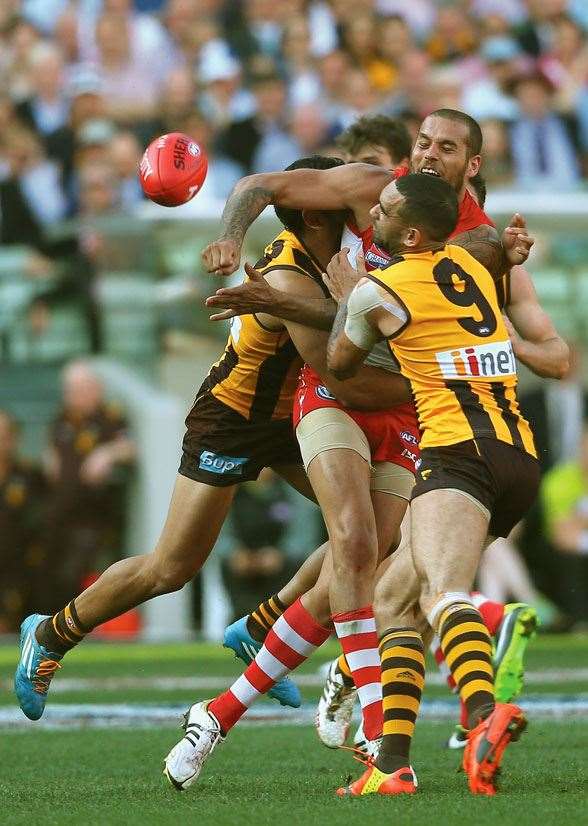

For those who watched him, several critical moments in the 2012 preliminary final against Adelaide repudiated that. Suddenly his sway, especially in moments of crisis, astonished everyone, even the wondrous Rioli, who was in receipt of the calmest and most adept of clearances. It led to a Hawthorn lead and a surge of self-belief that took them into the grand final. This wasn’t just “calming influence”. It was never merely that. This was cool brilliance.

The Shaun Burgoyne you’d have playing for your life was back – but really, he was never gone. A man can’t help injury. Burgoyne is Clarkson’s dream. His recruitment was a whack of inspiration, only it took a while for fans to comprehend this affable team man as an intelligence, an eerie awareness who whispers into the forward pocket and feeds it to dangerous men like Roughead with smart intent. Or mobilises out of the backline. Or calmly penetrates densely swarming enemy lines.

When the prolific possession-getters don’t stand up, Burgoyne holds the tension with outstanding individual efforts, especially in heavy traffic. After that 2012 preliminary final performance, Sam Mitchell nailed his impact when he said his addition made Hawthorn “much less predictable”.

His substitution for the injured Mitchell in the midfield in 2014 was stunning. His team had lost Franklin. They were shot through with injury and illness to their coach. They had every excuse to founder, but Burgoyne stepped forward and his team seamlessly made its way to the finals. His stats were not lofty, they just counted. Of the 25 matches he played in 2014 he averaged 22 disposals, 11.4 kicks and 10.6 handballs.

But stats obscure as many stories as they tell. The ice jumped out of my Scotch once as I witnessed Burgoyne stretch out a leg to toe-poke a ball on the run from a long pass before it hit the ground, flick it up, grab it, twist and dispose in the same motion, resulting in a game-turning goal. Such acts animate vast empires, start dynasties! The stats? One possession, one effective disposal.

There are games the Hawks wouldn’t have won had it not been for a few elegantly simple, patented Burgoyne contributions. That includes key moments in the grand final, after which teammate Matt Suckling said, with a shrug and a smile, “That’s why we got him over. In big games he finds something, and you just rely on him in the big moments.” Luke Hodge won the Norm Smith medal, ahead of Jordan Lewis and Sam Mitchell. Again, the player’s player wasn’t considered. Burgoyne is 31. When he retires, he won’t receive the sort of treacly headlines Chris Judd will, even though he was compared to Judd back in 2004, and Judd probably came out wanting for the comparison.

******

Done and dusted, his career won’t get the sort of power exequies the footballing lives of Ablett or Franklin will. Overlooked by football’s hype machine, Burgoyne’s merits will hopefully find their true level. The praise and respect he’ll receive from those who know their football will be well-deserved.

Last year was his most “consistent” year at the Hawks, they say. He got one of those nice “most consistent” awards. It would be a shame if Burgoyne is remembered this way. He’s been a jack-of-all-trades, master of all, dangerous and essential, needing few possessions to make enormous differences. They’ll know his worth when he’s gone.

******

“He doesn’t know it yet, but he’s been an enormous part of my footy career,” says young Derick Wanganeen, who went through Mallee Park long after Burgoyne was drafted. This careful delivery of the torch, this sheltering of the fire from winds of adversity and attentive fanning of the flame, is vital right now to Aboriginal sportspeople. Not only is it addressing the matter of Indigenous players cutting short promising careers, it’s beginning to affect their very identity as stereotypes change, according to Burgoyne. “The general stereotype of Indigenous players has changed from forward pockets to players who can play midfield, captain a team, like Adam Goodes and Gavin Wanganeen, and win Brownlows like those two. To be major players in the competition.”

In his part-time position as an AFL Indigenous projects manager, Burgoyne, like Andrew McLeod, has turned his attention to the non-existence of Aboriginal coaches. Aboriginal people are well ahead of Europeans in their understanding of the need for good role models as facilitators of good lives. Men like Burgoyne and McLeod are equipped to encourage Indigenous footballers to trade boots for clipboards. But it’s complex. The kind of deference and respect important to their culture might be counter-productive when it comes to speaking to other players with authority.

“There’s one or two working at it. Michael O’Loughlin is coach of the AIS AFL Academy. I see him as a great person to take that next step for Indigenous players and the AFL. You just need an opportunity and a platform to grow. Hopefully, we can provide them through these programs.”

He’s pleased his generation is breaking through, and their progress is being witnessed all around the country. The revolution, after all, is being televised. Through the all-seeing eye, we witnessed six Indigenous players running around in last year’s grand final – three for Hawthorn, three for Sydney. We’ve watched participation grow. We’ve seen disconcerting, if momentous, sights like that of Goodes calling out abusive members of the crowd. Those ugly few are finding it harder to hide. “Fans now are also taking a stand. People don’t want crap said in front of their kids. It’s great that crowds are now saying ‘enough is enough’. We’re getting better, but we’ve still got a long way to go.”

The vilification issue requires the sort of calm and intelligent presence Burgoyne has inside the boundary and beyond it. He knows racists are a minority. His sense of race and how it fits into greater society is subtle yet straightforward; acute enough to lead him to be the first to take to Twitter and express disappointment with Anthony Mundine’s race-based comments about Daniel Geale in 2013. Such an intelligent approach is needed if the vilification issue is not to lead to citizens “policing” one-another to undesirable levels.

Burgoyne feels strongly about his position on the AFL Indigenous Board. “We hope it will give us a voice. Over the last couple of years a few race things have happened, and though they’re dealt with quickly, it’s about the effect. Buddy was obviously vilified. Goodesy. We talk about those things. The homesickness – what kind of support structures can we put around a club? Do clubs have Aboriginal liaison officers? Do you move the families in? How can you make them feel at home and comfortable in the big city?”

Burgoyne deserves praise for the way he thrives and helps others flourish in complex and difficult circumstances. After he retires, they’d do a lot worse than to throw him into this one. He beats throwing money – he’s already proven that.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open