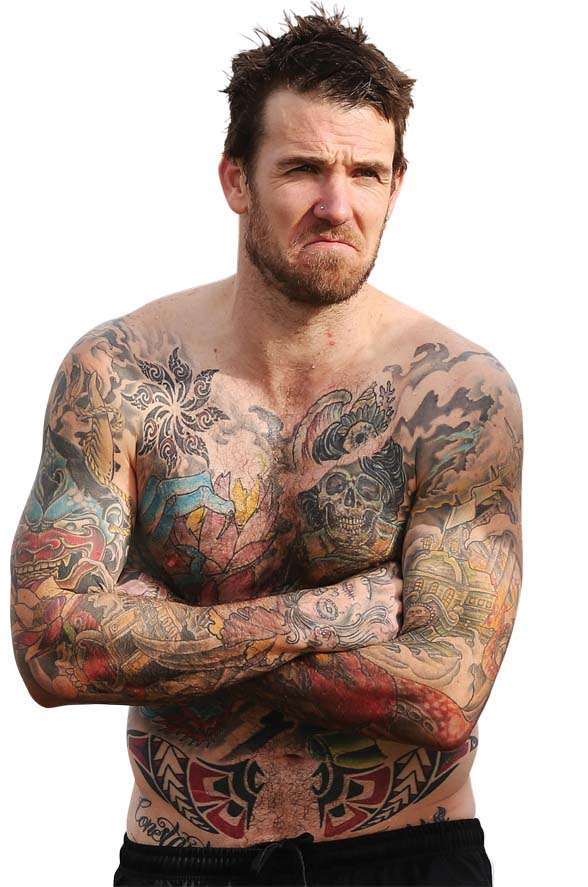

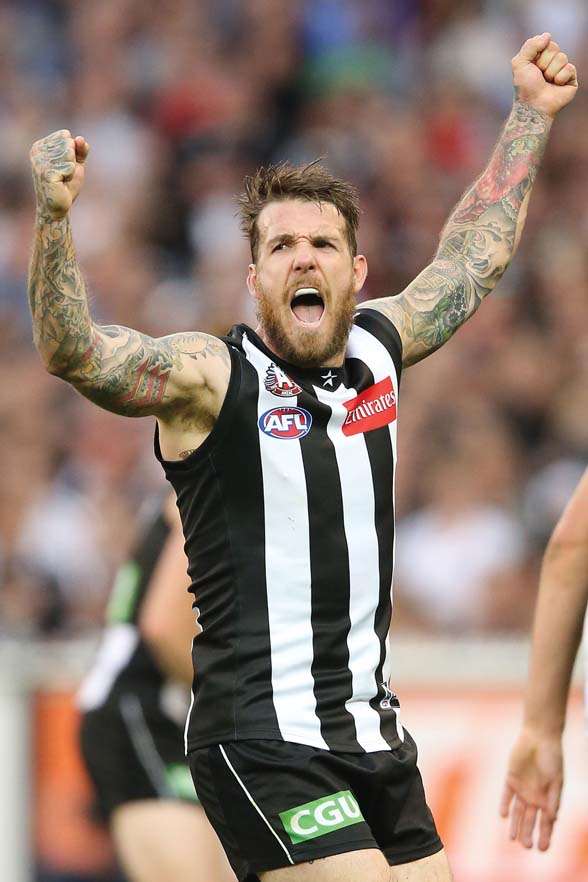

This Collingwood star seems the most unlikely of champion footballers.

The Dane Swan effect has at least partially relied on impressions. That’s how he scurried underneath the pack’s awareness in the first place. They say of him that what you see is what you get. But what you see is only part of what you get. In 2007, we were busy seeing something else – probably discussing where to clear floor space in the Hall of Immortals for Hodge and Judd – when Swan scampered through the tradies’ entrance and pinched himself a podium.

In fact, nothing Dane Swan says and does is contradictory in the slightest. The contradictions are in our heads. It’s hard to imagine any public figure who contradicts himself less. When he finally emerged in the media, in 2007, we were a little unprepared for the sharpness of his flat-toned, straight-faced wit because we thought he was a dullard. In fact, we’d pegged him as a top-shelf bogan icon; up there with Warne and Corby. In interviews we suspect his initial ripostes are set pieces, soon to be exhausted, and expect he’ll be sitting there like a stunned gosling the rest of the time. That’s what they expected the first time he appeared on The Footy Show, in his thongs, and they laughed from beginning to end. Even sarcastic Sammy Newman was rendered helpless by Swan’s crippling retorts.

He is no moron. He is not even an oxymoron. The way he lives and plays is some kind of complex trope. Teachers from his old school in Essendon aver that he had flair for language and respect for authority. You might be surprised to learn that this party creature, utilised by coaches as though they’re compensating for a deficit of attention, is in fact a reader, accustomed to focusing on the odd drawn-out passage. Yet, apparent every time he speaks is an impatience for the longueurs of play and social interaction.

He cares little about most things other people find important, and cares little who knows it. Once, arriving at the Lexus Centre the Monday after a heavy loss to Geelong, he was confronted by a journo who asked him if the “boys were concerned”. “Nah, we were happy with it,” he said as he brushed by.

The journalist chortled, “Happy to lose by 96 points?”

“Disappointed we didn’t lose by a hundred.”

Later, it was cited as he was presented Before The Game’s Most Valuable Smartarse award. “Ask a stupid question,” he said, proudly accepting the award. Well, as proudly as Dane Swan accepts anything.

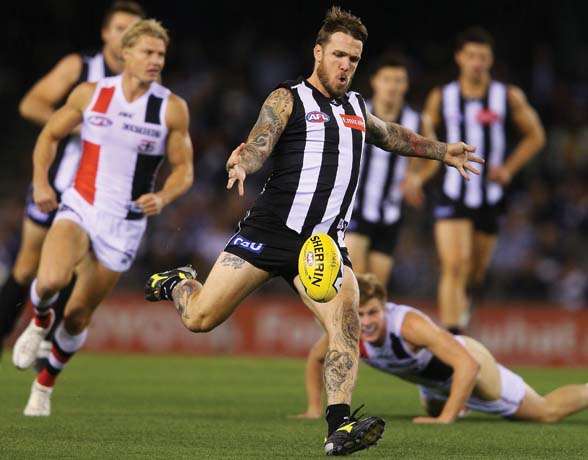

We were astounded by his surge through the ranks to become one of the best midfielders ever, because we only perceived him as dissolute, prodigal, unheeding of the demands of AFL football. Opponents still seem taken by surprise. They don’t see any of their own hard-won abilities in this one-sided, funny-running leftover who is, in fact, the most modern of footballers; who gets all the ball with, seemingly, few of the skills and little of the fitness opponents need to even approach his volume and quality.

Watch him long enough and you find unequivocal beauty in the game of this man named Swan who runs like a duck. Sway back, backside out, shoulders rolling – much like Parramatta’s Chris Sandow – he somehow glides deceptively. He has other similarities with Sandow, who’d love the opportunity to play his own game the way Swan does. Swan is quicker than he looks. He never fails to get the lion’s share. He’s a massive influence. He’s more athletic than he admits, and most give him credit for. With his one unacclaimed kicking leg, he’s hoiked the odd 70-metre match-winner with ease, and he’s kicked them on both sides, all with that distinctive jab.

But he’s a footballer. A good, old-fashioned footballer who appeals to a workingman’s aesthetic. He gets the football in a footballer’s way. The skills are sound. He rarely fumbles. Just like his old man, Billy, he’s expert at reading the game, being where the ball is getting his hands on it and sending it where it should go.

He’s taller than people think, too. At six-feet-one-inch, or 185 cm, he’s no small rover type, even though Collingwood reveres him now like Bobby Rose, Tony Shaw or Lou Richards. Swan plays like Robert Plant used to sing: with untutored technique – simple, sound, powerful and far-ranging. Like Artie Beetson played rugby league; like Thomson bowled and Lehmann batted.

But contradiction? No. That’s just people’s way of explaining his odd trajectory.

There are dazzling artistes who embody potential, and die with every note of the music still in them. There are bright prodigies, sung about from the beginning, eulogised when they die. There are outstandingly brilliant performers, like Dane Swan, who just don’t begin that way. Many take the expected path into dark forests of obscurity when their lack of essential skills, or even innate ability, lets them down. Not a word of their greatness is heard, unless a guide comes along. Swan, unlike another of his kind, Sam Mitchell, was lucky. His advocates happened to come from the biggest club in the land. They saw something, and drafted him way down at pick 58 in the Greatest Draft of All Time: the Judd-Ball-Hodge draft. Only Hodge is left of that trio, but Swan is way down no one’s list any more.

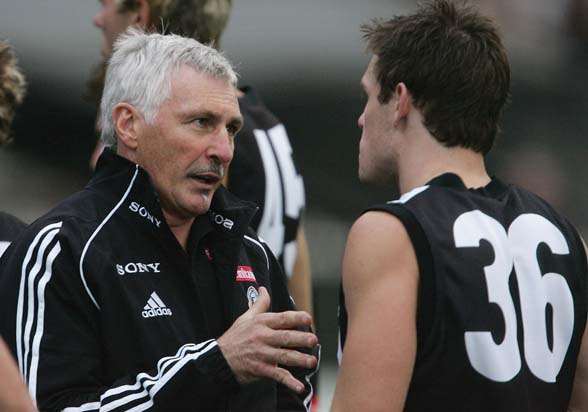

Collingwood knew their history. They pick a lot of players the way they picked Swan. This is part of their genius, beginning with Eddie McGuire, who surrounds himself with similarly astute judges. Eddie was always more than a voluble reporter able to use his chosen medium as an outlet for his vast repository of opinions. He sees things coming and anticipates excellently. He has an eye for a talented kid from an average background. He saw a “ball magnet with an awkward running style”. He also has an eye for pedigree. He knew Billy Swan was an excellent footballer, a late developer, who might have made it to the summit but for quirks others might call flaws. He saw Billy’s son, Dane, but understood he could go either way. Two years ago, McGuire told Martin Flanagan, “I’d seen it before with young blokes from his background – their mates either get in and support them, or they drag them down.” What he saw, in fact, was ambition and determination, not for football, but for having fun. But he, and Mick Malthouse, also saw he had a switch. It was a matter of accessing it. They did, and they threw it, just in time. It saved Dane Swan’s career and salvaged his life.

But don’t get Swan wrong. He knows when to flick it off again and default to fun.

Fun, after all, attracted him to the game, fun kept him in it, and the dying of fun will see him turn his back on it. Even today, Swan talks of football as though it’s not essentially interesting enough to sustain his interest without the fun factor.

Swan’s idea of a life well-lived is as uncomplicated as his football, and therefore his actions are never difficult to clarify. “Who doesn’t love a good time?” he once explained to that most dedicated and intelligent of footballers, Gary Ablett Jr. “You don’t like sitting around having bad times.”

When Swan was drafted by the Magpies as a 17-year-old, he was at “schoolies” week, on the Gold Coast, and that, right there, was an ambition fulfilled. Not being drafted – being at schoolies. He got the news, was told his flight back to Melbourne had been booked for the Monday, and because he’d only been on the Coast for a day, “politely declined”, telling Collingwood they’d need to wait until the week was over. No hope of an early return. Life was not about football. It was about – well, you know.

He was “a little bit dusty” when he finally turned up to training, late, after celebrating with “everyone in Westmeadows”. Assistant coach Dean Laidley cheekily informed the boys Swan was the kid who chose to stay at schoolies rather than train with them. It was enough to make club freethinkers Chris Tarrant and Ben Johnson like him instantly. Ironically enough, they’d become mentors of sorts.

His first awareness, ever, of football had everything to do with fun, celebration, and Billy Swan. Billy flourished during the VFA’s greatest era of biff, when Victorian Sunday arvos were taken up with live telecasts, and VFA players were as famous as their VFL counterparts. Billy, a VFA legend who still holds the games record, put on display, week after week, the genetic traits he’d deliver halfway through that career (1984) to a son.

Billy had done something unprecedented in those intensely confrontational, wild days of VFA: he left a team to play for its most savage rival. Port Melbourne thought Billy might be past it, at 32, and decided not to meet his pay demands. Billy played 219 games for Port, including four premierships and two Liston Trophies. Then, with Williamstown, he continued to be the leather-wolfing force he’d always been, pinching them a premiership win with one last-second, wonky, mongrel punt from a long way out, when it was thought to be beyond his distance. That was 1990. Little Dane looked on in stunned wonderment, his putty imagination preserving detailed imprints: the dodgy arc, the flapping flags, the uninhibited euphoria; his dad, a hero, the centre of jumping jubilation. Football was, suddenly, everything ... It looked like fun.

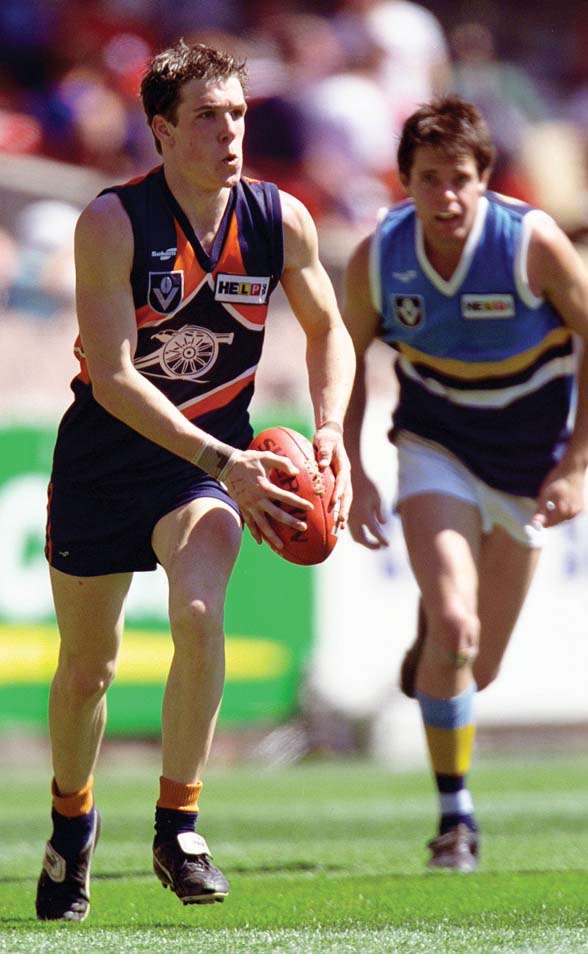

Dane was good enough to play with the Calder Cannons in the TAC Cup, but not good enough to stand out, it seemed. Even when he was shifted from forward pocket to centre, where his guileless, straightforward, see-it-get-it-kick-it approach instantly transformed his meagre bangers-and-mash into gourmet buffet, and many AFL scouts saw him play, impressions had kicked in like shutters: not much of a kick; abilities so average only a herculean stomach for toil would make them work at all – something he clearly didn’t possess.

Those impressions, eh? It was a safe bet they’d never be proven wrong. After all, talent rises to the top somehow. Flair flares, occasionally. Genius cannot help itself; confinement is not its thing. Swan was even dropped by the Cannons not long before Collingwood picked him up. For the first time and not the last, Malthouse stood at a crucial juncture in his career, and life. He addressed the Cannons. “Don’t worry what you’ve done so far. We focus on how you play big games.” Swan took his words to heart, and for the first time, played with hope. “I ended up being Cannons’ player of the finals, and Mick was true to his word, because Collingwood was the only club to speak to me.” In the final, the Cannons defeated a Geelong Falcons consisting of The Dux, Hodge, The Deluxe, Ablett, future Brownlow medallist Bartel, future premiership captain Maxwell. The urchin had a ball upmarket – plenty of ball, in fact.

Collingwood’s recruiter back then, Noel Judkins, was curious, despite word abroad concerning that work ethic. “Athletically, you thought, ‘Oh shit!’ But he didn’t fall over. He had that ducky running style, but knew where to go and what to do with it.” Judkins also commented that he was “not exceptionally fast”.

Yes, Collingwood knew their history, yet they baulked at the draft, taking three other picks. It looked as though the door had slid shut. Then, after other teams, exercising the new wisdom of recruitment and evaluating Swan “holistically”, passed him up, the ’Pies picked him at 58. Hawthorn were passingly interested before taking a young bloke driven with desire, Sam Mitchell.

He was drafted, but back then he didn’t see it as a lifeline. He was always destined for a good time. A football career was another matter. The draft camp was something else he missed for schoolies. The draft camp! For an aspiring AFL player, the draft camp is the first glow of privilege, singularity, specialness. It’s the Vienna Boy’s Choir; the Rhodes Scholarship, NIDA. He made it clear it wasn’t a priority. The only thing selective about him was his attention.

The feeling of privilege came slowly. He understands it now, after a deluge of mostly unwanted awards, but still doesn’t feel entitlement, or even pride, at his astonishing achievement over the past few years. It’s just as well he missed that camp anyway. There’s barely a test he’d have passed, and he’s in good company there – mostly the company of historical figures. Footballers, not athletes. “I must admit,” he says, “it’s easier to run for an incentive, when you know there’s going to be a footy at the end of it. Running around a track doesn’t really do it for me.”

It sounds way too straightforward. Dane Swan had something unsubtle, but it was large. There had to be subtleties in there to make it work, like the first gathering zephyrs of a hurricane.

Some saw a gathering force of nature. There were those who suspected it would stay confined. When Swan arrived at Collingwood, Nathan Buckley, a walking skillset still voracious for a premiership, still finding it hard to reconcile his newfound leadership attributes with an old intolerance for mediocrity and failure, wasn’t excited. Imagine Shane Warne, 1991 version – no achievements and a mostly untried talent that might turn out to be mere rumour – shambling into the Australian team Waugh captained eight years later.

To say Swan is almost habitually philosophical about anything that happens to him, for good or ill, is to attribute to him way too much introspection. He says it exactly as he feels it, and that’s easy, because feelings rarely come into it. “I’m sure [Bucks] didn’t like me much,” he said in 2010. “I was this kid who just wanted to get out and party with his friends and thought he could use AFL football as a way to have a good social life.”

For most of his first three seasons, he didn’t look like holding down a senior spot. He was considered a reprobate, a delinquent, not worth the trouble. Even Magpies fans wondered. While the scrubbed boys of the 2001 draft were all coming along nicely uptown – Judd, a Brownlow, Hodge, trump card in a great team, Ablett, on his ascent, Ball, an extraordinary influence, Pavlich, Dal Santo, Bartel, high achievers all – a more sensitive man than Dane Swan might have been mortified, paralysed, by the feeling of down-at-heel inferiority.

None of this was helped by an incident in 2003 that changed his life in many ways when it could have changed his life in many other ways. Out with his cousin Aaron Ramsey, and Wayne Carey’s nephew, Kade, he was involved in a fray with bouncers. It was accepted by the court that he and Ramsey merely joined the fight to aid Carey, but the incident permanently affected one of the bouncers.

Now it seemed he matched the caricature. He was a cleanskin then, not a tatt in sight, yet he was depicted as a thug. That hard, thin-lipped Glaswegian stare and larrikin manner now took on a more sinister aspect. But it wasn’t him at all. Swan had never been in trouble with the law, and had never really been a fighter.

His form hadn’t been great at this time. The board wanted to sack him. Still, his advocates stepped in. Malthouse was forgiving, if stern. Whether it was manic denial, a sudden maturity, an existential moment, no one knows. Swan just knows “the penny dropped”, and every year after that was a noticeable improvement on the year before. “I just tried to repay the faith he had in me. I worked as hard as I could, and tried and tried. I still wasn’t any good as a footballer, I just tried a lot harder.”

The man he was born to be rose up. He always knew where a ball was going, but he developed something – ability or willingness or fitness – that enabled him to be there to meet it. Much of it had to do with that “work ethic” business he’d heard so much about. Suddenly there were believers at every turn. If it was a conspiracy, it fulfilled its aims. “Benny Johnson grabbed me in the pre-season and said, ‘Look, I know you’re not as fit as me, but just try to hang in with me as long as you can.’ That’s what I did for as long as I could until I’d drop off. Taz [Chris Tarrant] got hold of me in the weights room and said, ‘Just try to keep up with me.’ It sort of went from there, just trying to keep up with those two and their work ethic.”

Johnson says, “We never knew how good he was going to be back then.” Meantime, he struggled until he found a way to engage. The moment he realised he cared didn’t escape Malthouse’s notice. It happened after a game in mid-2005, during which Swan was given a bath by Melbourne’s Adam Yze. When Swan dissolved into tears, Mick saw another self-activating switch, and moved in. After all, sitting around having bad times is not Swan’s thing. That was it. No more back-pocket flounderings. They played the eventual premiers, Sydney Swans, the next week, he thrashed forward star Ryan O’Keefe, and was never the same again.

Considering those limbo seasons, the fact that he now sits second only to Greg Williams on the list of all-time career disposals, averaging a slim 0.01 fewer than the immortal centreman, is astounding.

Swan is now the circle turned; the tipping point; such a complete throwback as to be the most modern of footballers; a child of interchange. He can be durable when the occasion demands, but he’s most effective as a burst player. No one’s rotated more. It suits him. It helps him defeat taggers. Because of his recuperative powers, he’s often off the field for mere seconds. Swan is quick over ten metres. He’s effective because he’s deceptively so, like a boxer who keeps clopping opponents’ chops because his reach is longer than they realise it is.

Like Warne, but without the affectations of mystery, he’ll tell you why he’s effective, leaving it to opponents to do something about it, and sometimes the absence of mystery is enough to make them second-guess.

“I’m not a natural athlete by any stretch of the imagination. I’m not a great endurance runner. That’s why you see me on interchange a lot. I can hold my pace and recover reasonably well. The way the game has gone has helped me. If they restrict the number of interchanges, I probably won’t get a game.”

The merry prankster’s troubles didn’t end with that 2003 incident. In 2010, the premiership year, he walked away without retaliating after being punched square in the face in a nightclub. He was admired for it. But there have been bans for drinking in the week before a game, fines for unauthorised appearances on The Footy Show; public utterances from his coach, Buckley, that he’s “a handful”. For small social peccadilloes, he’s both contrite and unapologetic. What else? Besides, the club loves Swanny.

Every year, the Brownlow, the last place on Earth he wants to be, tells us where Swanny’s at. The 2007 count was where he burst into our consciousness – and he wasn’t invited. He led most of the night and threatened to win the thing. The cameras couldn’t find him, our memories tried to bring him into focus. The little highlights packages accompanying each round’s votes presented a cumulative picture of an under-the-radar ace. Meanwhile, at Alan Didak’s place, decked in a Spiderman suit, Swan flippantly fielded calls from his manager who begged him to suit up more conventionally, in case he won. No dice. It was mad Monday. He’d been bigging it up all day, and was about to go out. He came fifth, management and club were relieved, and viewers were left with an unexpected impression of sustained brilliance.

He had a woeful 2014 by his standards, and posted an Instagram shot of himself in jocks and a bowtie, evidently headed for the Brownlow count. He was invited, but chose not to attend, spending the night having Sam Newman’s face tattooed on his backside – a lost bet.

He was favourite in 2010, lost, and showed little strain. He won it in 2011 and gave every impression he’d rather have been somewhere else. He’s learned that personal awards just don’t do it for him. Three Copelands, five All-Australians, Leigh Matthews Awards for MVP. The accolades have flowed like mead in a mediaeval feast hall. He doesn’t care much for them.

In his Brownlow year, 2011, Swan demonstrated his voracious appetite for oxygen. He streeted most other players in almost everything, statistically and in the esteem of anyone in a position to judge. Then, around the halfway-mark, he sustained a quad injury. His form spiralled. The club gave him time off to train at altitude in Arizona, and he returned bursting. He averaged over 35 possessions per game, and despite missing a match, won the Brownlow by a record number of votes.

The class of 2001 have hit their 30s. Not many are left. Most of those picked above Swan sank from view or enjoyed a brief prime. Hodge endures. Ablett is rightly proclaimed the greatest of centremen. Mitchell is a surprising Hawthorn immortal. But it’s Swan, the man with no secrets, who continues to surprise and mystify. Is it ironic that the closer he comes to respectability, the more ink his skin acquires? It’s not unexpected. A few years ago, he was publicly making no promises about playing beyond 30. Now he’s 31, as good as ever, and his team is better off for it this year. Time has flown. He must be having fun.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)