Climb aboard for the PNG Hunters' outstanding debut Queensland Cup season.

As each player enters the boardroom, he places a deflated football on the sideboard. It is Friday afternoon and the PNG Hunters have just landed in Brisbane. For weeks the broody-looking head coach and former PNG national player, Michael Marum, has forced the players to carry a football with them everywhere. He says it will teach them a lesson about ball possession, because he’s sick of them “dropping the fucking ball”.

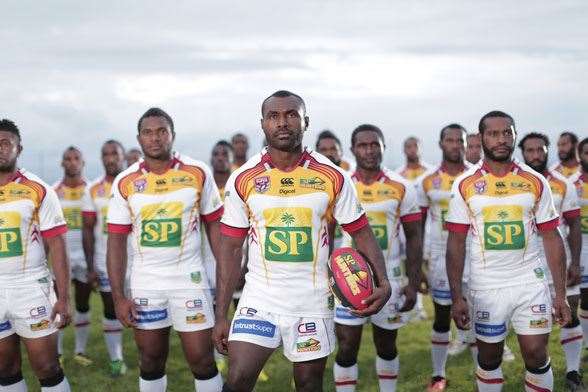

It is week 37 of the Hunters’ continuous training camp. Once all the players are assembled, Marum speaks to them in angry-sounding Pidgin. The gist of his tirade is that there are three rounds left; if they’re to reach the finals, they have to win their next two games. This (2014) is the Hunters’ first year in existence, let alone in the Queensland Rugby League’s Intrust Super Cup – or “Queensland Cup”. To qualify for the playoffs out of 13 teams would be a miracle. And they’re so close ... just one position away on the ladder.

Aussie Brad Tassell, the Hunters’ CEO, speaks to the team next. He has baiting words to motivate them: “Wynnum was the most vocal club about you not being in the cup. I have clear memories about that. Remember this on Sunday – they didn’t want you here. You are playing for your family, your country ... and your right to be here.” Before they leave the boardroom, the final say comes from the team’s strength and conditioning coach, Jason Tassell, Brad’s younger brother. “Remember, it’s not like home. So drink the tap water here, carry water at all times ... and your ball.”

The players begin to file out with their deflated footballs. As they walk past Brad, who is casually sitting on a table near the exit, wearing his runners and a Hunters nylon tracksuit, he slips each player a crisp, green $100 note from a stack in his hand. “Away allowance,” he says. “Don’t spend it all at once.”

Welcome to the Hunters: a mixture of professional rugby league team, boarding school and military camp. The players are paid equivalent to a lawyer in Papua New Guinea and their average age is 23. They come from the highlands, the lowlands, the islands and the coast and have formed a team of brothers, representing their county in a national first. Some are the sons of politicians, some left university to be in the team. Some are yet to finish high school and some have never seen a washing machine before.

For Queenslanders, the Intrust Super Cup is footy at the state level. To Papua New Guineans, it’s the most exciting thing to happen to their beloved game in decades. Papua New Guinea is the only country in the world that considers rugby league its official sport. The Hunters pipped the popularity of PNG’s national team, the Kumuls, who’ve suffered through years of poor performances. The Hunters’ Facebook page is the most followed sports site in the country, with over 27,000 fans, compared to 13,000 on the Kumuls’ page.

General manager of QRL competitions Jamie O’Connor says that in 2014 the “Hunters factor” lifted the QRL’s profile to new heights. The QRL’s social media numbers have never been stronger and crowd attendances set new records. The NRL won a seven-figure contract with a PNG television station to broadcast the Intrust Super Cup in 2015, discrediting past perceptions that PNG has no commercial potential.

The Hunters opened a pathway for Papua New Guinean players to enter the NRL without having to move to Australia at a very young age. In December, when the latest round of contracts was handed out to Hunters players, the South Sydney Rabbitohs signed Wartovo Puara and Thompson Teteh, while Stanton Albert joined his brother Wellington at Penrith (the latter was scouted by the Panthers during the Hunters’ 2014 pre-season). Back in April, Hunters prop Mark Mexico signed with the Cronulla Sharks.

When a Hunters boy is picked up, Brad counts it among his greatest successes, drawing on his impressive connections to make sure it happens. League legends Wally Lewis, Andrew Johns and John Gibbs travelled to the Hunters’ camp in Bomana to launch the team’s 2014 season. As well, Mal Meninga has been involved as a team patron from the beginning. “I think because of the Hunters, in a couple of years’ time we’ll see a flood of PNG players in the NRL,” the Raiders, Maroons and Australian legend beams.

The achievements of the team’s first year were unimaginable, but the real triumph was that the Hunters existed at all. They rose from the ashes of a failed PNG NRL bid and a broken PNG rugby league administration system. The cultural, financial and logistical obstacles the team had to overcome in its own county and in Australia were immense.

In September 2013, the Hunters finally got the go-ahead from a cautious QRL. Brad and his team would have three months to pull a professional football team together for the 2014 season. Convincing the QRL to admit a PNG team to its all-Queensland league took years. Some of the established clubs were uncomfortable with how an international team would function. Funding was a hurdle, too. The Hunters’ budget has to cover flights, accommodation and security for all the Queensland teams travelling to PNG for Hunters’ home games. This is on top of the club’s own travel expenses arising from regularly playing in Queensland, and of course housing, feeding, training and paying players and staff. The PNG Government and a host of mostly PNG private sponsors came together to help meet the significant expenses.

“Brad and I reckon we could write a book about what we’ve been through with the Hunters,” reflects Jason – in between squabbling with his brother over directions from their conflicting GPS devices, as Brad drives in the pouring rain to the team’s first coaching session since landing in Brisbane. Both in their late 40s, they have no clue how to navigate through the city. They were raised in Mt Isa and Cairns before following their own football careers to Sydney. Brad and Jason speak with a hint of North Queensland drawl in their vowels. Brad often begins his sentences with “mate ... ” They’re unpolished, but polite. Brad can turn on a sheeny sport’s management persona when needed. The Hunters is the third club he’s helped build from the ground-up along with Northern Pride and the Cairns Taipans. Jason and Brad joke with each other like chums on an adventure. And they are. They’ve left Australia, neither knows for how long, on a legacy-building mission in the thing that’s consumed their entire lives – footy.

The Tassells are among the most respected rugby league families in Australia. Brad, Jason and their other brother Kris all made it to national and international sides in their own playing careers. In 2013 their Dad, Tom, received a by-nomination award from the NRL for 40 years of service to local clubs. (There’s a junior trophy competition named after the family in Cairns.) “Our work ethic we learnt from our Mum and Dad,” declares Brad. “Our parents have been involved in local rugby league ever since I can remember ... secretary, vice-president, president ... You just can’t learn that in a book.”

Brad lives and works from the Holiday Inn in Port Moresby, Jason lives with the team. In January 2014 the Hunters set up camp at a run-down, mouldy police college in Bomana on the outskirts of Port Moresby. Jason and the rest of the coaching staff, all Papua New Guineans, lived in close quarters with the players. Establishing a regular food routine for 23 professional footballers was the biggest challenge of all. “If we let our hired cooks do the shopping, we’d be eating white rice and a tiny bit of meat, breakfast lunch and dinner,” says Jason. “We couldn’t train our guys twice a day on a diet like that. We’d end up killing them.”

So the coaching staff took turns going to market and cooking for the team. Jason also doubled as an electrician and a security guard, keeping watch over the players at night. Mid-season, the Hunters moved camp to the sleepy island village of Kokopo in New Britain, a large island province 500km from the mainland. They had to start the whole set-up process again.

While Jason was in the thick of material difficulties, Brad was tackling a culture change and a vocal group of Papua New Guinean critics. “Both Jason and I have received death threats,” claims Brad. Why? “Because we have proven that the people who ran rugby league before were incompetent. They have been shown up for what they are and they don’t like it.”

Most of the criticism is from former league officials, some of who were disposed of during Brad’s appointment to CEO of the PNG Rugby Football League, which includes his role as CEO of the Hunters. The motives for the conflict are vexing and complicated for all involved, but what’s certain is Brad’s approach is succeeding in a way PNG has never seen before. “Ninety per cent of the country loves what we’re doing and supports us because they can see the good work,” says Brad. “There’s a minority who have their blinkers on and use every means possible to undermine anything we do.”

Brad came to PNG in 2011 to work on the country’s NRL bid, a consortium set up to achieve PNG entry into the NRL – the ultimate honour for the league-fanatical nation. When Brad got there, the bid had been a slowly sinking ship for years. He began turning the focus away from the NRL to the QRL. But underlying problems prevailed; PNG’s rugby league administration was rotten with corruption and power struggles, which affected the sport from a junior level right up to the national team. When PNG Minister for Sport, Hon. Justin Tkatchenko, took over the ministry in 2012, his directive was a demolition and reconstruction of the country’s national rugby league governance. The Hunters would be key to the rebirth of the sport in PNG.

So much raw talent ... You hear it said over and over again about PNG and rugby league. But this rawness can sometimes translate as immaturity. The first morning in the hotel, some of the players didn’t show up for their routine “piss piss”, a urine test taken by head trainer Solomon Kulianasi for dehydration monitoring. “Solo” voices his disappointment at the morning team meeting: “You know the schedule. You don’t do this back home, why do you do it here?” One player slept in and has missed the entire morning program.

Head coach Michael Marum erupts: “It’s not a fucking holiday! This is an important game. Stop fucking around! If your room-mate doesn’t wake up, wake him up!”

Coaching staff are aware of Brisbane-based fan girls staying in the dive-hotel next door. They suspect this is why one boy is a no-show. Late-night rendezvous are strictly forbidden. Drinking and chewing betel nut are banned, too. The penalty is usually game disqualification. “We’ve probably dropped our best players for discipline issues four or five times and still won games,” says Jason. “You have to show the boys everyone is the same when it comes to discipline.”

This kind of control on the players’ lives isn’t normal in the Intrust Super Cup. Other clubs let their players live as they please: go home every night, eat what they want, get drunk when they want, see who they want when they want ... Most have full-time jobs and train twice a week, not twice a day like the Hunters. It might seem like the Hunters have an unfair advantage, but they’re playing decades of catch-up against teams who’ve had years of playing together, professional coaching and working systems in place.

The team is scheduled back in the boardroom for a video session run by Michael and Jason at 9am the morning before game day. Jason has spent the last two hours chopping and syncing video of the opposing team’s last game for the presentation. The players trickle in and weigh themselves before sitting down. Baby-faced Hunters captain Israel Eliab, or “Izzy”, sits front and centre, his team draped around him. He is 23 years old but looks much younger than the other players. Early in the season he contracted the measles. The whole team had to be immunised, just one example of a uniquely Hunters-type of problem.

Eliab plays guitar every Thursday night for the team’s Christian fellowship, which all boys attend. He speaks in the tranquil tones of an island boy: “We come from different backgrounds, some fortunate, some not so fortunate, but we come together for the love of footy ... We live like a family in a house together. It’s shaped us to become brothers.”

Sitting to Izzy’s left is shy Stanton Albert, from a small village in the Southern Highlands. Albert’s front-rower physique dwarfs his captain’s. He is 19 years old. Or so he thinks; some of the players from remote parts of PNG aren’t too sure of their birth years. Stanton’s full beard does make him look much older than 19, but when he’s interviewed, his soft voice becomes strangled, making him sound like a nervous boy. Stanton’s confidence as a young man, however, is on full display on the football field. In June last year he was named Player of the Tournament at the Under-19s Commonwealth Championship in Glasgow, a two-day, eight-nation Nines event involving the likes of Australia. After his Hunters commitments in 2014 are over, he’ll begin a two-year deal with the Penrith Panthers in the NRL. “My family tells me to listen to the trainers and coaching staff and do what they say,” he says, “so I listen and follow them. I want to play my best.”

Wynnum-Manly Seagulls Club is located on the fringes of the eastern suburbs of Brisbane. The crowd this Sunday is a sea of the Hunters’ yellow, red and black. And double the usual attendance, which has become the norm wherever the Hunters are in town. As the team runs on to the field, Brad, Michael, Jason and the rest of the coaching staff sit tense, hunched over in their small row of plastic chairs on the sideline. At half-time the Hunters are down 14-4.

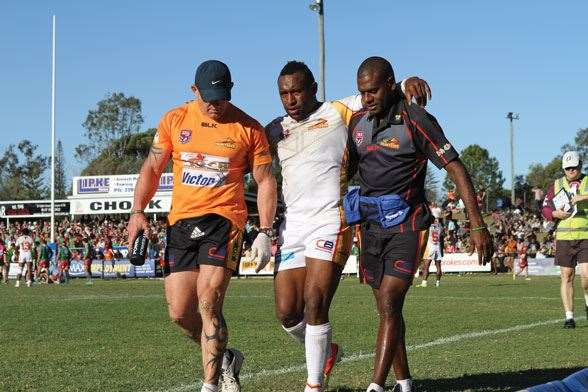

A Papua New Guinean man behind the fenced-off drinking area near the sideline clutches at the barrier’s metal bars. He cries out in Pidgin, a murderous, haunting bawl, over and over again. Tears are streaming down his cheeks. The Hunters lose 28 to 10. When the final siren blares, the Hunters slowly move off-field, carrying the weight of their loss with each heavy step. Silence hangs in the air as they gather on the sideline ... but only for a second before thrilled supporters run out to embrace them. Mostly Papua New Guineans – grandmothers, small children, entire families, and young women holding out their phones.

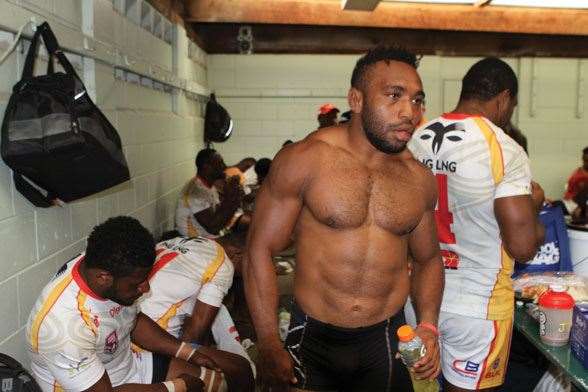

Once back in the change rooms, the Hunters players are held there for what seems like an eternity; the winning team nowhere to be seen for an hour. Once released, a white Aussie kid who plays under-12s poses for a photograph with their halfback Noel Zemming. He’s asked why he follows the Hunters. “Because I like to go for the underdog.”

- Ali Winters

Postscript: The Hunters needed one more competition point (a draw would’ve done) to reach the five-team Intrust Super Cup finals. They eventually finished 6th: 14 wins, 1 draw and 9 losses.

******

(Just days after the magazine containing this story went to print, CEO Brad Tassell announced his resignation from the Hunters, citing continual death threats against himself and his family, and a continual campaign to slur, undermine and tarnish his image.)

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open