The New Year’s Test, 1994. Australia had to win. Couldn’t lose. Until Fanie de Villiers begun hooping the ball about with that awkward, low-slung action.

The New Year’s Test, 1994. Australia had to win. Couldn’t lose. Until Fanie de Villiers begun hooping the ball about with that awkward, low-slung action.

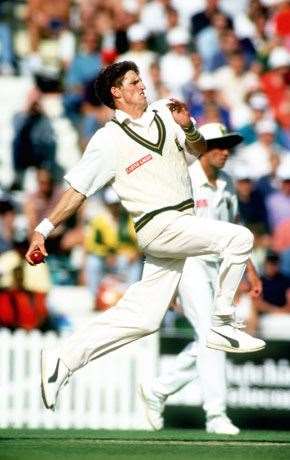

Fanie de Villiers erupts in that Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground in ‘94.

Fanie de Villiers erupts in that Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground in ‘94.Images: Getty Images

Warney had run through the South African batsmen – seven in the first dig, five in the second. Come the fourth innings, Border’s men needed just 117 runs to go one-up in the series. Couldn’t lose. Until Fanie de Villiers begun hooping the ball about with that awkward, low-slung action. He picked up the first four wickets, Donald fractured the middle order, then de Villiers came back to root out the tail. When McGrath spooned one back to the Transvaal quick, the Australians had fallen six runs short. I was 13, sitting in the top tier of the Noble Stand as that carnage unfolded, as the Australian batsmen trudged to and from the sheds. It nearly ruined my summer holidays. So it was under an eerie pall of childhood angst that I sidled up to “Vinnige Fanie” while he was in these parts, taking the new ball for the South Africans in the XXXX Gold Beach Cricket series.

Fanie, I was at the SCG on day five of the 1994 New Year’s Test …

You were there that day? Yes, a lot of Aussies didn’t go. They thought it was a wrapped-up game …

Good memories?

The lasting memories for any sportsperson are to win games from behind. It’s huge. You know, we’ve played at Lord’s, the hallowed ground, and everybody says to win there is the best. If you win a game in three days it’s actually an anticlimax. But when it’s a fightback, when you lose 11 of the 13 sessions in the game but still win, then it’s a lasting memory. When it comes to emotion, that game ranks as number one of all.

Do you still have your remote control car from that tour?

My room-mate that tour was Pat Symcox and he took it. He’s still got it. He told me that when we turn 60 he’ll give it back to me, so we’ve got a fair bit to go before I can get it back! But he claimed it because he said he paid a hell of a lot of money with all the fines we had to pay – we had a deal in our room that any fine we would cut in half – so he reckoned he’d paid for that car 30 or 40 times over.

There seemed to be a lot of animosity between yourselves and the Australians on that tour …

Yeah, it started in the Queensland match, where Allan Border was captain. Obviously we were the new boys on the block and we didn’t have a feel for what we should be expecting, and that day I had a big problem with taking the wicket of Trevor Barsby. I finally got him out on 99, but I think that was the fourth time I got him out. No neutral umpires or anything and I thought there were a couple of dubious LBW decisions not going my way. The last ball before lunch I went up again for an LBW, not out again (the only way we were going to get a decision was if the ball went underneath the wicket), so I walked straight off, didn’t even collect my hat from the umpire. Outside the sheds Kepler Wessels was standing there with Mike Proctor and I said, “These bloody Aussie umpires, they’re all crooks.” Typical young guy who’s a bit emotional. Allan Border overheard and he retaliated by asking who the hell was I to slander the umpires. I was on my way to him, very aggressively, when Kepler got in between us and said to AB, “Listen, if you want to talk to anyone, you talk to me. Leave my players alone.”So that set the base of the tour. And we had a tough tour. If you look back, that’s a tour we should’ve won. The match after that Sydney Test was in Adelaide. I went in as a nightwatchman and batted right up until drinks in the afternoon and when I lost my wicket, six or seven wickets fell in about 20 minutes. The decisions from Darrell Hair and Terry Prue were absolutely ridiculous. So, until this day, we believe, as players, that that’s a Test we should’ve drawn and that’s a series we should’ve won. So, yes, a lot of animosity – quite a mental battle going on behind the scenes.

Fanie de Villers in full flight. Images: Getty Images

Fanie de Villers in full flight. Images: Getty ImagesGiven that, were you surprised by the atmosphere of goodwill on this recent tour?

Not really. I think the moment you trust yourself and your game, you’re more relaxed. I must admit that on the tours after our tour in ’94, the bowlers weren’t good enough to win games. Over the past decade, every single tour that came our way, myself and a couple of guys would analyse how many wickets certain players were worth. And we never could get past 14 or 15 wickets. We knew we were going to get a hiding in Australia because the bowlers weren’t there; Shaun Pollock didn’t have the back-up he should’ve had. And that made it hard. When a team comes touring knowing they have a 20 per cent chance – perhaps less – of taking 20 wickets, it creates pressure. But the moment you’re a good team, and you know you can win a series – because you’ve got the bowlers, the batsmen, everything – you’ll play a better game of cricket when it comes to the social side of it. And that’s what the boys have got now.And yes, also there’s the factor of county cricket and the IPL, where the boys know each other so much better, they’ve got a couple of mates playing on the other side. That plays a big role, too. When we started we didn’t know anything. We’d never even said hello to these guys.

Were you surprised at how toothless the Australian bowling attack was?

Not really, and I’m not even saying that tongue-in-cheek, because I’m a firm believer that you guys had a 50-60 per cent advantage before every match started purely because of Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath. The Aussie public, the Aussie selectors, the Aussie system have been spoilt tremendously to have two players like that. And I’m telling you now, without those two, 50-60 per cent of your team is not there. That’s a fact. I can prove it to you with stats, I can prove it to you with attitude, I can prove it with anything you want. You guys have carried players over the years because those two have won you Test matches. Without them, everybody has to pull their weight, everybody’s under pressure to take the wickets. For example, remember how we used to carry Jacques Kallis? In his 14th Test match he made his first 50. So we carried him for a long time. The poor bloke was nearly in tears sometimes, but we kept telling him, “My boy, you’ve got the potential, you’ve got the shots, you know what you look like in the nets. Just keep going. You’re going to get runs.” But we could only look after him because we were winning Test matches. I would like to know how many players the likes of Warne and McGrath looked after in the system, and gave them more games than they would otherwise get because the team was winning. It’s amazing the influence those two guys have had on your system – I would’ve taken on you guys anytime without Warne and McGrath. It would’ve been a walk in the park when it came to attitude.

Dale Steyn took a swag of wickets over here with his late swing, and yet there doesn’t appear to be a fast bowler in the Aussie team capable of swinging the new ball. Why?

Swinging is an art, and the art comes in if you’re lucky enough to be born with a wrist that is cocked just before delivery. You get two types of swing bowlers. One who changes the ball in his hands, seam towards the slips so the ball can swing; and the other one who holds the ball right on the seam but cocks his wrist to the left and so delivers the ball pointing to second slip. But often, with pace, that wrist cock goes. So you get, say, Allan Donald, who could bowl outswing when he was trotting in, but the moment he started bowling quick, his head fell away and everything else, including his wrist, pointed towards middle stump. So he lost that swing. Dale Steyn has the ability to keep that wrist position and swing the ball late. He’s a cock-wrist swing bowler. And that makes a huge difference. It’s just luck of the draw to find a guy like that, then you need clever selectors to target that guy and say, “We’re going to make you part of our system at any cost.” So you can’t point fingers. Cock-wrist swing bowling is a special commodity. If it comes your way, you’re lucky.

Fanie De Villiers. Images: Getty Images

Fanie De Villiers. Images: Getty ImagesWhat were your thoughts on Graeme Smith’s captaincy in Australia?

I was very anti-Smith when he first got picked. I’m a firm believer you’ve got three tiers to Test captaincy. The first is the most important one: in your own country you must have a captain the people love and look up to and respect and adore. That gives you more bums on seats back home because he is literally the link between the public and their cricket. So you want a captain who’s been around, who’s grown on the people, who can then take the game of cricket to the next level in the public eye. Then the second tier: will the senior players take all their knowledge, all their seasons of experience, and push that through the captain and into the system? The senior players must want him to be captain, because if that doesn’t happen, the poor bloke’s out there on his own. And the third tier is the knowledge, the man-management, the savvy, the handling of the media. Now when Graeme started at 22 years of age, he probably didn’t even have one of the three. But over the past five or six years, he’s grown on the people and he’s grown on his own players and he’s become knowledgeable, played enough years to make important decisions. He’s now out there to impress, and that’s what he’s done. He’s grown in stature, it’s wonderful to see, and hopefully he’s going to be around for the next five years.

Inside Sport recently ran a story (A Captain’s Knocks, #205) where the South African author suggested that Smith wasn’t loved at home because the South African cricket public were still wounded by the Cronje scandal. Is there truth to this?

That’s bullshit. What Hansie has done, he’s set a standard for the loveable captain, a guts-and-glory captain. And he didn’t have that at the start. Yes, he was respected and he was a good-looking guy, so the chicks loved him. But he grew on the people and within two years everybody loved him. So he set a serious standard of what a captain should look like and how the people should perceive a captain. He earned that. And Graeme Smith has now earned his time in the spotlight. He’s worked up from a nobody, to an arrogant little guy, to somebody who knows things and is respected. He’s done his time.And to get back to the South African public being jaded with the gambling thing, that’s nonsense. Really analyse Cronje’s career – year by year, all the good that he’s done, the impact he’s had with the players, with the public, all the betterment he’s done. Yes, at the end of the day he stuffed up, and the poor guy’s not here anymore, but that can’t overshadow the good that he’s done. It’s impossible to overshadow what he’s done.

Do you think South African cricket can now dominate like Australia has done for the past 15 years?

I don’t think so. I’m going to stick my neck out here and say I can’t see it because we haven’t got a normal society back home. Our society has not normalised. A lot of hassles are there, taking place now, that influence the quality of the game. A lot of players get picked who shouldn’t be picked, a lot of coaches aren’t of a standard they should be. It’s taken us 12 years of cricket to get quality – right through from the players, to the coaches, to the selectors – but you’ve got to

have a real strong society, a good system out there, to dominate for a long period of time. You guys have had it. Yes, you had Warne and McGrath, but you would’ve been top two anyway with the quality of cricket you play here. If you really want to know what the quality of our cricket is, you should play your state teams against our state teams and you’ll be very surprised to see the difference. Our system back home is not solid yet. It’s heading toward it and we all support it, but there are huge gaps. So until that’s sorted, we’ll compete in the top three for a long time, but we can’t dominate like you guys have.

Is cricket making headway in South Africa’s black population?

We’re doing a hell of a lot for development. But if you’ve got 34,000 black schools in the country and only 300 to 400 of those play cricket, then you’re not really finding all the talent you should find. We’ve got 20,000 white schools and every one of those plays cricket. That makes a huge difference. So our cricket players of colour come through the white schools. They don’t come from the development program, unless you find, say, a Makhaya Ntini and put him in a top cricketing school where you have top coaches nurturing him. So just out of our development show, I’m afraid to say, not too much will happen. But you will find a bit of flair here and there, and that flair needs to be nurtured and taken into proper cricketing schools.

– Aaron Scott

Related Articles

Playing From The Tips Ep.100: Webex Sydney, Honda LPGA, Mexico & Kenyan Opens

Burmester claims LIV Golf Chicago in three-way playoff