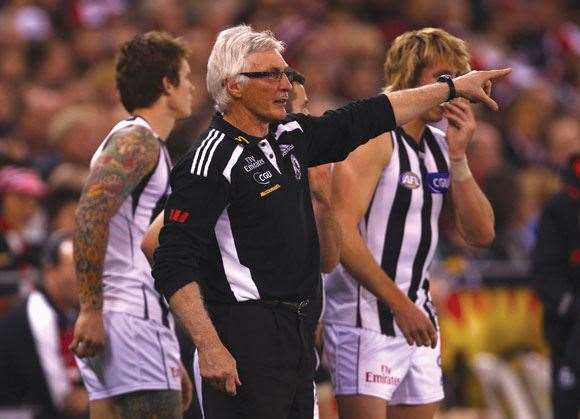

Leonine Mick Malthouse, who, in costume, made the corporate buttoned and badged tacky black-and-white tracky almost debonair.

photos by Getty Images

photos by Getty ImagesLeonine Mick Malthouse, who, in costume, made the corporate buttoned and badged tacky black-and-white tracky almost debonair.

I’ll miss the Malthouse theatre. No, this isn’t to announce the demise of Melbourne’s landmark ham factory, but rather to lament the departure of another institution of the Melbourne stage: Mick the Magpies’ coach.

Leonine Mick, who, in costume, made the corporate buttoned and badged tacky black-and-white tracky almost debonair. Unpretentious Mick – you could almost sense his relief that he didn’t have to find something new to wear every week. Urbane Mick of the post-match pressers, ever-hectoring, always illuminating, irritability a reach away, fronting a phalanx of reporters infiltrated with surly critics, his little private ironies carefully concealed as they writhed on the end of his sarcastic barbs, or a spiky stare. Misunderstood Mick, whose indignation was sometimes mistaken for spite.

Ageless Mick, who’d accepted his crown of white with grace while still a young man, but made it known he’d be making few other concessions to age. For all the intensity, the public wrath, the occasional tears, the press tension that marked his decade in the footlights, Malthouse never overacted. Like a Buckley pass, his soliloquies were long, but nicely-weighted, if at times a little abstruse. Those critics would lampoon him for that, but rarely when he was in the room. His last two years stunned them into silence. Malthouse was, for a decade, the most credible actor in the Magpie melodrama.

His performances were never stagey, like the uptown hokeyness of identities he shared the boards with. One suspects he was never really their favourite. He never wore their scent, for a start – the one called compromise. Malthouse was one who saw the necessity of the cloak, but wasn’t fond of the dagger. This too would draw denunciation, but he bore it with a level crown. He’s a complex man all right, but never a pain-in-the-arse enigmatic. A man in control, a decision-maker, yet free of that harsh pretence of invulnerability, and pained by collateral damage. Arcane, at times, but never impenetrable, he welcomed the loyal, the honest and the dedicated into his sanctum – and his teams – and therefore his coaching was absolutely a reflection of his character.

Over 28 years Malthouse took three lowly sides and gave them self-belief. Success followed – not always in premierships. Yes, there were three of those as well, for good measure, but there were also those great triumphs, Footscray 1987, and Collingwood 2002-3 – relatively unacclaimed performances. He’s particularly proud of those brave Bulldogs and premature ‘Pies. Neither had the right to be there, given their circumstance and cast. Two years ago, some were whispering – those churlish detractors were triumphantly proclaiming – that Malthouse was finished. Three grannies and a premiership later, he exited the stage, having left behind one of the most scarily-effective units in AFL history. Most importantly, though, he left them wanting more.

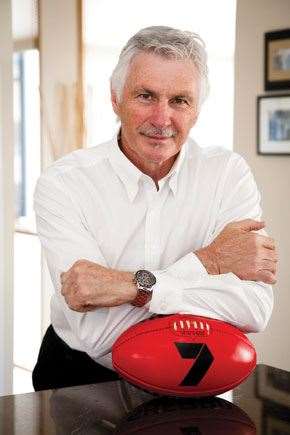

Back in October you said you’d take a few months to decide what you were doing next ... You’re doing commentary at Seven. What else have you decided?

What are you doing there? Leadership and mentoring. My goal is to see it become the number-one sporting university in Australia. When a kid desires to be involved in sport, be it journalism, administration, physiotherapy, I want La Trobe to be first choice. I’ve also accepted an ambassadorial role with Bank West. I’ve been involved with leadership for a number of years. On-the- job training, dealing with parents, coaches, staff, supporters. The whole gamut.

You’ve joined a prestigious commentary team at Seven, including some gun recruits. What do you hope to give commentary?

photos by Getty Images

photos by Getty Images

Where do you find inspiration? What do you read, watch, listen to? As a coach you’ve got to be abreast of things. Nothing stays the same. You’re either part of change or you invent change. I read } history more than anything. I’m reading a history of Jerusalem. It gives me an insight. I’ve always wanted to visit it. I’ve read a fair bit on Afghanistan. I want to know why our troops are there and what they’re up against. I read about great people. History shapes the next phase of our lives.

Do you feel potential was lost - that a lot more could’ve been done - when you left coaching? That was the contract. It wasn’t going to change. Move on. Once you’re a coach, you’re always a coach. Barassi will always be a coach. Allan Jeans died a coach. I won’t say I don’t miss it, but you’ve got to take the great times – I’ve been able to represent five clubs as a player and coach. I’ll take those times and redesign the rest of my life, use some of those components – discipline, structure, teamwork.

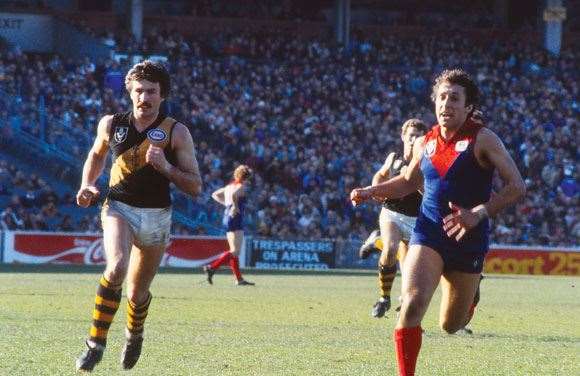

You’ve been around long enough for your coaching career to be described as an epic. What chapters stand out? I got sacked first game I played, for St Kilda, the last practice match. Told I wasn’t going to make it. Sent back to Ballarat. If you accept what sometimes seems inevitable ... I wouldn’t be sitting here, for a start. I was invited back to play reserves and by the end of the year I’d played three seniors finals. It started with luck, but I started to play okay. I could’ve got more out of myself, looking back. I could’ve worked harder. But I know that when I was done, I didn’t have one game left in me. So, to go and coach Footscray... again, how that came about was a mystery. Well, it turned out the preparation I did as a player helped. Then West Coast gave me an opportunity. Then Collingwood. To go from St Kilda to Richmond - Paddy Guinane and Alan Schwab gave me an opportunity. It’s what you do with it. Grab it, work hard and you never know what’s around the corner. Wasn’t all beer and skittles; Collingwood were bottom, West Coast 11th, Bulldogs hadn’t been in finals for years. You haven’t coached until you’ve coached a bottom side, under massive pressure. Don’t rate yourself until your fourth or fifth year. The first couple are honeymoon, the third year they’re starting to sort you out, fourth you’d have to show something to get that side in a good position. On the other hand, the moment you start to think you’re the reason those things have occurred – one, you’ve got a big head, and two, it’s incorrect.

So, going against popular belief, premierships are not the measure of a sporting coach? In 1985, Footscray made the finals. In ‘86, we were under financial pressure. In ’87, we were forced to sell players, we had a lot of under 19s kids in the seniors, no seconds, we lost the first three games by 42 goals and played the reigning premiers in round four. We won, and made the finals by half a game. That was one of my better years. I suppose it’s what you do with a club. Do you leave it in a position to be defended? Is it financially set? Is it player-sound? Has it got credibility? Has a good supporter base been taken on a good ride? There’s a lot of ways to look at a coach. Brad Scott’s done a wonderful job at North. I see a stable organisation. Only one side’s going to win a premiership. Success is measured in many ways.

So what about 2002-3? Fantastic. Brisbane were a fantastic side. To get where we got from 1999 was a wonderful achievement for all the people at the club.

Who are the heroes of your story? People who think they’re on the periphery, but the club can’t do without them. Rain or sun, good years, bad years. Successful players sometimes become successful people. Stephen Wallace Andrew Purser, Dougie Hawkins in his own way. Brian Royal, Glen Jakovich, Guy McKenna, John Worsfold. Rob Wiley. Many are heroes in my eyes. Paul Licuria, Anthony Rocca, Scott Burns, Jimmy Clements - outstanding people, outstanding family men, outstanding individuals.

In 2010 and 2011, elements of the media would’ve given anything to see cracks in the Collingwood plan to hand over to Buckley. Did you guys feel any pressure? You’ve got to ignore things that don’t relate to your job. I’ve never viewed coaching as a right. It’s a privilege. I was always part of a team, not an individual. You’re the most visible. I did the job I thought was best for the club and respected everyone’s position, because certain jobs are not easy. The club itself, the supporters and players, are too important to get embroiled in petty things that could destabilise it. I thought we lost momentum in 2011. It’s a credit to the players that they stayed as focused as they did. If you had that year again, you’d like to see it flipped over. We had momentum early. If we had injuries and suspensions early, we’d have lost a few, but we’d have recaptured momentum and gone into the finals with better preparation.

What personal philosophy helped you to balance it all and still come out a success? Part of my job is to ensure what players do as individuals is good for the team. You’ve got to feed the egos enough, but we only succeed with a common goal. If at times I haven’t liked the attitude of certain people, you have to make a decision. Some have moved on. Football clubs are not about being everyone’s best mate. You’ve got to balance it all, respect one another. I respect Eddie and his role, the administrators and their roles, the players and their roles. When they break from those roles and make parts of the organisation crumble, you’ve got to make sure it doesn’t permeate. That’s the first sign that the organisation will fail.

What was that rocky relationship with the media all about? You get painted as a person with no media friends. That’s not the case. The game can’t exist without media, and the football media can’t exist without the game. I like to think they’ve done their homework, listen, respond to the answers, and respect the fact that the interview’s often not long after the game. The thing about me and journalists is bizarre; you have one argument and you’re tarred that you don’t get on with anyone.

photos by Getty Images

photos by Getty ImagesTeams you coached played different brands of footy. What were the common things each had – the non-negotiables? Solid defence. To use a soccerism, good strikers; people who can score. But that’s peripheral to discipline and unity. Eighteen blokes with one goal and one method. Loyalty. Then you’ve got hope. Then you put in strategies, game structures. They come about because of changes in the state of the game. You’ve never won successive premierships, but you did get right back up there.

What are the main challenges a premiership-winning side faces? Expectation. It’s been 75 years since Collingwood won a premiership and actually played off the next year. We did it in 2010-11. That shows how hard it is at Collingwood. Expectation is an entity in itself. Hunger. You can measure how fast you can run, how high you can jump, but you can’t measure hunger. You’ve got to rotate players till you find the hungriest, and inspire the rest. Clearly an individual’s got more chance to be regularly successful, because a team has so many components. Ten might stay hungry, ten are hungry in their first year, but have this fraction of “it doesn’t matter now, I’ve won”, and they contaminate the others. Blokes like Federer are driven to be number one, then driven to be number one again, and again. But what if Federer was playing doubles? The more numbers you add, the more parts to the machine, the more complex it gets.

When you made that handover agreement with Eddie and Bucks, you were undergoing some bad times. All good now? Your mother doesn’t get resurrected. Your daughter’s baby doesn’t come back.

How did you feel about Ben Cousins? Very sad. When I coached him I enjoyed the way he played. He’s a terrific bloke. It looked as though he was over certain areas of drugs, but you could see he might go backwards at first. To see such a young, energetic, enthusiastic person affected like that – I feel terrible for Ben and his family. I know his family. Chris Mainwaring’s passed. You reflect a lot about your time in football and who’s got up and who’s suffered.

What’s the best coaching achievement you’ve seen in football? Who’s the best coach, or who coached the best side? That’s what you’ve got to ask.

Paul Roos? That doesn’t stand out more than Worsfold the following year. Or Matthews’ three-peat. Or Chris Scott’s 2011. It’s hard enough to win them. It would take too much away from anyone who’s won one to say.

In your pantheon of inspiring or remarkable human beings, are there any footballers or football people? No. The AFL is no more than a pimple on a rhinoceros’ backside. Mandela is significant. What Thatcher did in Great Britain, Ghandi – world significance. Gorbachev. What Ferguson does for soccer, what individuals do at AFL level – it’s sport. There are far bigger matters. When did you decide you weren’t up for the director of coaching role at Collingwood? It’s not that I wasn’t up for it. It wasn’t going to fit. That was very evident.

When did you realise that Collingwood couldn’t win the 2011 Premiership? Twelve minutes to go. But I knew it was going to be tough, leading into the finals. Momentum is one of the greatest things on Earth. We’d lost momentum, and to beat West Coast in that first final was unbelievably satisfying. With players injured and suspended, we went in against a side running hot. To beat Hawthorn in the preliminary final was outstanding. We had no right to win.

Is that why you were so visibly affected that day? You get caught up. It was 75 years since the club had played off, and I could understand why, and I thought all our plans ... I knew we had to hold Hawthorn and not let them get their game together, because we were underdone. To see those plans start to take effect, hold on, just make sure they don’t get away, and we forced that issue about six or seven minutes before three-quarter time. I noticed a shift. Their frustration started to show. Once that happened we were a real chance. Then to get the lead and lose the lead and get it back ... if you’re not emotional in sport, you’re not emotional about anything. Hawthorn knew they hit us with their biggest shots and couldn’t put us down.

One thing you share with Sheeds is you see people in terms of time and life and where they are on that cycle. Where did you get that? I try to understand where people are, so I can give them resources to be better. People have a right to feel special. When you give an opportunity to someone, they want to feel like a contributor. So when their time comes, they think they’re needed. When you think you’re needed, you have ownership. When you have ownership, you surrender last, and you’ll go to the death. James Clements was a bit unsure of himself, but with surety he was one of the outstanding players I’ve coached. Anthony Rocca was sadly devalued by many. We needed him out there.

You’ve said you don’t try to be anything but what you are. What are you, Mick? You’ve got flaws, acknowledge them. Address it. I tried to give people a chance. I believe in doing it together. If you think you’re the most important person, you rob others of their importance. I’d like to think these things transfer to other areas of life.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Socceroo star's message to kids: Don't be an AFL player