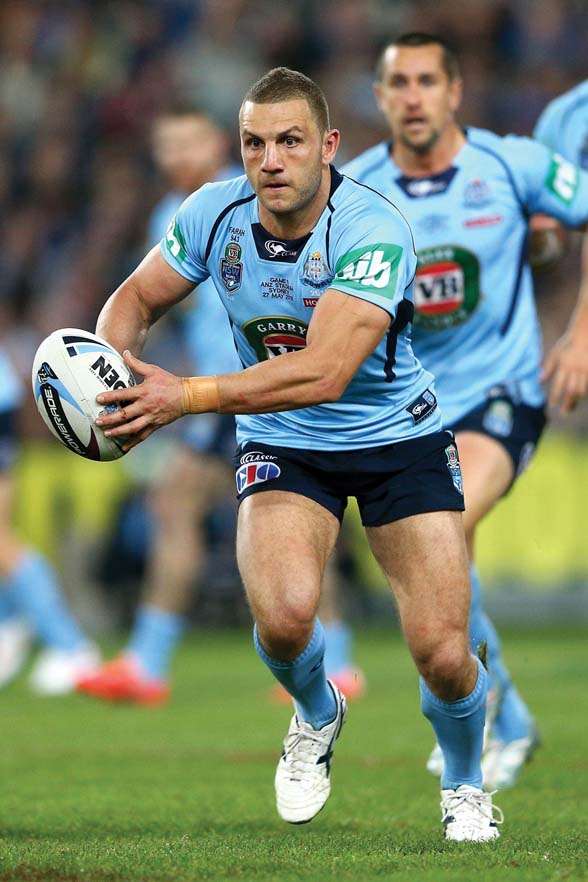

Robbie Farah has evolved into a leader of men, on-field and off.

Farah's day job, away from Origin, is inspiring his black and gold army to great things. (Photo by Getty Images)

Farah's day job, away from Origin, is inspiring his black and gold army to great things. (Photo by Getty Images)By Matt Cleary

Robbie Farah has evolved into a leader of men, on-field and off, at the highest level of the game of rugby league. But who does he follow?

In days just before mobile phones, a dozen or so kids from the streets of Campsie would gather every day after school for a game of footy on an unused green of the South Campsie Bowling Club. It was full-on tackle rugby league. Farahs versus the rest. And it was the furnace that forged Robbie Farah.

They called their ground "The BOC" and they still aren't sure why - where the "O" came from ... it's one of those things. But it was rock-hard and fast, and the boys broke bones, split heads, lost a heap of skin. They were furious games with street rules, played until they could no longer see.

And always in amongst it was Robbie Farah - two, four, even five years younger than the rest - mixing it up. With three older brothers and a couple of cousins giving it to him, he'd head home crying occasionally. But he'd always be back. The kid loved it.

He was skillful, nippy and creative. He had a chip-and-chase in him. But his talent was never writ so large that it screamed Future First Grader. He was no prodigy. But he was ultra-competitive. Tell him he couldn't do something, he was a bull terrier savaging a tennis ball.

His brother David would stir him up, knowing it'd drive the kid. No way you'll make first grade. No bloody way. Robbie would fume and declare that he bloody would so play first grade. One day he bet his brother a thousand bucks. Another day, when Robbie got a call from Tim Sheens, David got a call soon after - head to the bank, bro!

First cousin Charlie Farah was a BOC boy, grew up in the same street. He remembers stinking hot summer days, 35 degrees, and there was Robbie, sitting front seat of his old man's Kingswood, windows wound up. The kid was creating his own sauna.

Charlie chuckles at the memory. "He might've put on a couple of kilos in the school holidays and because he didn't want to lose anything to other guys, he'd sit there in the sweatbox trying to sculpt his physique. We'd be going to the pool or the beach, and he'd be locked away in the Kingswood, sweating it out. [Laughs] Who'd even think of that? He's 13 years old!

"But that's him: when he gets his mind set on something, he just does everything he can to get there.

"But then we never thought - none of the boys did - that he'd scale the heights that he did."

"His commitment and dedication took him where he is, even then you could see it in him," says BOC regular and close mate Frank Samia. "There were always bigger, faster, more skillful kids. But Robbie was the most disciplined. That's what sticks with you: he was focused on making it from a young age."

LEBANON

Inside Sport meets Robbie Farah on the Friday after Origin One in the Leichhardt office of his long-time manager Sam Ayoub. His arm is in a fresh sling after Justin Hodges' horizontal slam-tackle. He's in discomfort, certainly, probably a bit of pain. You'd have forgiven him for brushing us. His mate Tim Moltzen copped the same injury a week before, went off to suck on a morphine whistle. Farah stayed on, made 60 tackles.

Ayoub was manager of Lebanon's rugby league team and with coach John Elias made the call to give 18-year-old Farah a crack at halfback in the 2002 Mediterranean Cup Test against France. He hadn't trialled because of a Tigers development tour to New Zealand. But Elias and Ayoub had seen a highlights reel and took a punt. Farah says the international match in Tripoli, playing alongside Hazem El Masri, cousin Charlie and old Frankie Samia from the BOC, was the making of him. "I'd been playing junior grades here and had a decent season," says Farah. "But Johnny still took a punt, saw something in me. And I started halfback against France. We got a great reception. Lot of locals there, lot of family of the boys. It was a great occasion."

Driving to the ground, the team's security was tanks from the Lebanese Army. After Farah scored the first try ten minutes in, the stadium lights went out. "We were all panicking," smiles Farah. "But they came back on and we won 36-6. And I took a lot of confidence out of it."

Back in Sydney there was the World Sevens, again playing for Lebanon, again playing against grown men. This time NRL first graders. Back in Jersey Flegg (Under-20s) there was a trial match against the Roosters. Farah was captain. Ten minutes in he thought, How easy is this? He'd been playing against men and found the age-group game slow. At half-time the Tigers were up by 40 and he'd scored three tries. Watching on was a good man to be watching on: Tim Sheens, the coach in his first year at the club. "It was the first game Sheensy had seen me play," says Farah. "I got out of the shower and he said, 'Well played.' And from that day, things started to move pretty quickly."

And thus on June 8, 2003, Farah became Wests Tigers player No.67 when he ran off the bench against Manly at Leichhardt Oval. And for the boys from The BOC, watching from the stands and on the hill, it was as if a part of themselves was running out there with him. "I had goosebumps," says Charlie Farah. "We were all rugby league fanatics and to see one of your own on such hallowed ground, it was very special." Frank Medina agrees: "He did us proud, 100 per cent."

Dene Halatau debuted same game. He was 20, Farah 19. Both had been called up the day before by Sheens. "I remember he was wearing white boots at training," smiles Halatau. "Sheensy told him to colour them in black. Coloured boots weren't a thing back then." Farah went home and coloured his boots with black texta.

Yet his confidence remained. Halatau remembers Farah's first touch. "That first set, he got out of dummy-half, kicked early in the tackle count, put it into touch. It was a nod to his confidence. Usually a young kid's dishing to the halfback. But Robbie saw the space, backed himself to make a good kick, and thumped it into touch 20 out."

Farah says he's always had confidence. "I've always backed myself. But it's come from working hard. When you know youíve put the work in, you can have confidence."

Farah would play four games of first grade off the bench in 2003, another three in 2004 before his knee needed reconstruction. And then came 2005, a season Wests Tigers are still celebrating today.

2005

Robbie Farah began 2005 in reserve grade and sat on the bench to watch first grade's whacking by Parramatta. In the sheds afterwards he had a yarn with Todd Payten. The big prop shook his head and said, "Mate, we are going to win the wooden spoon." But halfway through the season, "something clicked" says Farah. Tim Sheens' investment in youth began to bear fruit. And the young Tigers, given their head and a little license, began to play. And to believe. And to win.

They beat everyone, these babies, these skilful, skittish, two-year-old racehorses. Farah, Halatau, Benji Marshall, Bryce Gibbs, Liam Fulton, Bronson Harrison, Chris Heighington, all 19, 20, 21. "We all felt comfortable and encouraged to bring our talents," says Farah. "Kids can be overawed and play not to make mistakes. But we were encouraged to play the way that got us there. And the older players grew a leg off that. And we became this team that was unbeatable. By the end of the season, the finals, I knew, I truly believed, that if we played how we could play, then no one could beat us. It was a special feeling."

Farah remembers the Round 22 game in Canberra, a hard place to win. The Tigers were down 14-nil, scored 22 unanswered points. On the bus on the way back up the Hume, Farah was telling all the boys: We can do this. We can win the whole thing.

Guaranteed a top-four spot, they dropped their last two games. But the Monday morning first week of the finals "everyone was just buzzing," according to Farah. "We put 50 on the Cowboys. Everyone talks about our attack and we had a good combination in Scott Prince, Brett Hodgson, Benji and myself. But our defence was underestimated. In four games we only gave up 30 points. It was remarkable."

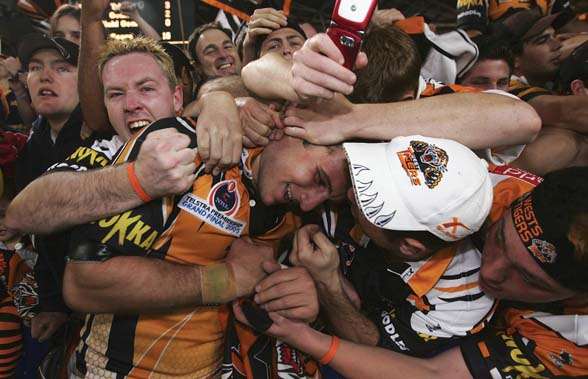

Farah, Benji Marshall and their fellow Wests Tigers pups were too young to know they weren't supposed to win the 2005 premiership. (Photo by Getty Images)

Farah, Benji Marshall and their fellow Wests Tigers pups were too young to know they weren't supposed to win the 2005 premiership. (Photo by Getty Images)AUSTRALIAN STORY

Peter Farah left the mountain village of Bhairet in the early '70s to seek his fortune in faraway Australia. He had little education, very little money and no English. In Sydney he took jobs in factories, menial stuff, saving enough to head back home and find a wife. Soon enough he did - Sonia. The couple married after a six-month courtship then headed to Australia to raise a family. Four sons and a daughter followed. Peter drove a cab, woke at 2am every day.

The youngest, Robbie, says the old man's work ethic rubbed off early. And it was because the old man did the rubbing. "He wanted us to have something he didn't, so he pushed us, drove us, when it came to schooling," says Farah. "He was adamant we went to school, went to uni.

"For him and mum to move to a new country without a word of English, without education, without a dollar to their name, you look back and really appreciate it. They raised a family of five children who are all educated and doing well. It's testament to their hard work."

Sonia Farah saw each of her sons earn a university degree. Robbie graduated in 2011 with an economics degree from Sydney University. She passed away in the middle of 2013, a crushing blow for the family. Robbie was bereft. He was still living at home. His mum treated him like her little boy. Her passing, knowing she was crook, were the worst days of Farah's life.

But if something good can come from something so tragic and sad as the passing of a parent, it's the realisation, or at least the reinforcing, of what's important. Farah found new appreciation for his family and friends. They rallied, turned up at his house. Blokes, doing their best to offer condolences. Blokes don't do that stuff well. But the boys had a go, did their best for their mate. It meant plenty.

After the World Cup in 2013 Farah travelled to the old country to visit family. His mother was one of 11 children. Farah has eight aunties. His grandmother is still alive and healthy. "It was emotional but it was also great," says Farah. "It is a beautiful country, beautiful people. Every time I visited an aunty's house they'd have a feast waiting. And they wouldn't take no for an answer if you said you were full. I put on four kilos in a week."

Farah connected with cousins, all his age. Spent time in Beirut at nightclubs and bars, and late in cafes drinking coffee among blokes smoking hookah pipes - "the bubblies," as Farah calls them. His cousins don't really understand rugby league but with the internet, YouTube and even live streaming State of Origin, they're starting to appreciate that rugby league - and their famous cousin - is kind of a big deal.

ORIGIN PLAYER

Like all dominant play-makers, Robbie Farah has options, and moves he can rip off at speed. With the ball in two hands, moving out of dummy-half in that nicely balanced way of his, Farah can hit runners short or long, he can go himself, he can hoof one of his manifold varieties of kick. He's a dangerous man. He's the go-to man on clutch plays. And he has the best one-handed scoop-and-scoot since Benny Elias. "He'll always have a crack," says Dene Halatau. "It doesn't always come off, but that's the nature of football. When you're playing against him it's about giving him the respect knowing he can create but not standing off so much that he can do what he wants. He's very good at assessing his options and picking the right one. As an opponent, it's about limiting options."

Justin Hodges tried to limit Farah's options in Origin I by slamming him into the ANZ Stadium turf and roaring "concussion!" Farah would stay on - he pretty much had to. Before kick-off he'd given his men one final, passionate rev-up: "It doesn't matter how fucking tired you are, you get up and get back in that line! Your mates need you! It doesn't matter if you've got a fucking broken arm!" Farah recalled the speech as he lay nursing what he suspected could be a broken arm. "I was thinking, 'Oh shit, that bloody speech. I can't go off!" He made 1000 tackles with a bung shoulder instead.

Queensland enforcer Justin Hodges slammed Farah to the ANZ Stadium turf in Origin 1... (Photo by Getty Images)

Queensland enforcer Justin Hodges slammed Farah to the ANZ Stadium turf in Origin 1... (Photo by Getty Images)In the 72nd minute, the scores locked 10-all, Farah and his halves, Mitch Pearce and Trent Hodkinson, had a "communication breakdown", according to Farah. "We had a penalty and myself and the halves got together, spoke about the set. We'd run our structure then work back towards the posts. Which we did. If you look at the set we went right, shifted it back. Play-the-ball was under the posts.

"Mitch was out to my right, Trent was to my left. We'd trained for it: in case Mitch was pressured he could pass to Trent. For some reason, I don't know why, we didn't take the shot. Between the three of us there was communication breakdown. Not sure what they saw but I was expecting them to take the field goal. And we buggered the set-up, kicked it dead on the last.

"Then Queensland went down and kicked the goal. And then we stuffed it up again. I passed it to the wrong person, 'Duges' [Josh Dugan] got a shot away, struck it well, but ... "

Yet Farah's message at full-time was "heads up". "There were a lot of positives. The way we defended was outstanding. So many sets on our line, we held them out. They threw everything in the second half, and to give up only one try gives me a lot of confidence.

"We should've executed better. But the way we dominated in the first half, it's nowhere near over yet. We can tie it up in Melbourne and, like we did last year, we can win at Suncorp."

... but he remembered his passionate pre-game speech to his troops and stayed on he field, doing hat inspiration thing he's so good at. (Photo by Getty Images)

... but he remembered his passionate pre-game speech to his troops and stayed on he field, doing hat inspiration thing he's so good at. (Photo by Getty Images)POWER PLAY

Last year Gorden Tallis took a morsel of gossip Farah had proffered in-confidence 18 months previously and told the world (of rugby league) that it was evidence Farah was behind the putsch to have coach Mick Potter removed. That Farah had told Tigers management that he wanted himself and his players removed from the decision process was lost in the white noise. Such is the perception of Robbie Farah's influence at Wests Tigers.

"Robbie was very disappointed with Gordie," says a team-mate. "It was a bad time for the club, the team, what was happening with our coach. And Robbie was trying to distance himself and the players from whatever decisions were going on in the boardroom. But it didn't come out that way. Gordie saying what he did, it added fuel to the fire and it was unfair.

"Robbie loves Wests Tigers, he's a career man, and that's the way it'll stay, I've no doubt. He took it to heart. All he cared about was the club and looking out for the boys. And this stuff was all misdirected at him and it was poor form from Gorden."

Last time Farah spoke to Tallis was on the field after a match when he upped Tallis for the rent. Farah doesn't want to talk about the spat, doesn't want to fuel any more fires. And then he does talk about it. "I always put players first and what's best for the club first. I'm a passionate bloke. But to be painted as the person who had that influence [over Potter's sacking] was completely wrong."

Yet it's there, undoubtedly, a perception that he's the most powerful man at Wests Tigers Inc. Farah jokes that if that were true he should be paid commensurately. "Hire me as the CEO, as a board member. I don't know what the other guys are doing. They can pay me to do all that stuff."

He shakes his head. "Mate, seriously - as a captain I'm the voice of the players. CEOs, board room guys, they do talk to you, they ask your opinion. After 13 years of service I think I'm entitled to an opinion. It's up to them what they do with it. I don't do the hiring and firing."

Sometimes he does the re-hiring, however. When James Tedesco (also a client of Ayoub's) was "forced out" to take Canberra's offer, Farah got involved. "If I have power and influence, I see it as helping the players. James Tedesco, I felt I needed to get involved. The coaching situation last year, I tried to stay out of it. Contrary to what was being said. There's times when I can get involved and others where I shouldn't."

Says Ayoub: "Nobody was questioning his influence when he did everything to keep James Tedesco at the club. And everyone at the club's happy: we kept James Tedesco. It was because of Robbie. He got involved and he got people to the table when others at the club couldn't.

"Now, only James Tedesco, his family and I know what happened at the time. James didn't want to go. I don't dictate to players where they should go but he was put in a position whereby he had no other option. Robbie was filthy, not only with me but more so with the club. However when he understood James' situation he went about trying to ensure that James could stay. That is what you want of your captain. He always has his players' interests at heart."

In 2008 Farah thought he had to go to the Gold Coast. He'd made up his mind. "When it came to the crunch, I couldn't bring myself to leave. I've been here since I was 12 in the local district, spent two-thirds of my life with the club. It's where I'll finish. Well, unless I get forced out!

"But no mate, I still enjoy my footy, I enjoy doing my best for the club, leading the boys, and trying to get better. I still enjoy giving it everything on the field and at training."

Farah has two years left in his current contract and will see how his body and mind goes. He is aged 33. "I'd love to be part of a successful club. We owe it to our fans. We have great kids, the nucleus of a good side. And mate, when we win another comp, I'll retire on the spot. Regardless of the money, I'm not fussed. It would be very special to captain the winning Tigers side and lift that trophy in front of 80,000 in your last game of footy. Wouldn't mind going out like that."

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)