For Inside Sport’s April 1992 edition, respected rugby league writer Neil Cadigan wrote this feature about Peter Sterling. On the field, Sterlo’s act was squeaky clean. Off the field, it had been a different story.

Wednesday at Parramatta Stadium. Physical fitness guru Rowland Smith – the man many Eels believe to be either a maniac or a masochist – calls his troops in for the dreaded eight-lap time trial. The oldest and possibly the smallest of the 50 gathered players, halfback Peter Sterling, winces for a moment, then focuses his mind on the ensuing nightmare. He jokes that he doesn’t sleep for three days before one of these trials. He’s been belted by 100kg front-rowers, suffered the agony of three serious shoulder injuries, and played in five grand finals and 18 Tests – but this moment on the training paddock is as daunting and important to him as any of those games: more important now than last year, and the year before that.

For 14 of his 32 years, Sterling has had a fear: of quitting. He knows that during the time trial he will give himself the choice of dropping back a gear, of saying: "We'll only give it 70 or 80 percent this time and it'll be okay."

What if he gives in? "As soon as something as simple as that happens, it's time for me to retire," he says later. “If I quit at training, I've got a chance of quitting on the weekend. If there were two minutes to go, with us two points ahead and I quit, that could cost us the game. I couldn't live with that."

Friday night on the Gold Coast - pre-season. Peter Sterling stands up in front of more than 100 salesmen and executives from Australian Cash Registers who've been having a jolly time on a week-long seminar at the lavish Kooralbyn Valley Resort. Many have come from Aussie rules territory, many have only a passing interest in sport. But Peter Sterling, sportsman, is not here to be the Friday night entertainment; his address is part of their business training. His message: motivation is something personal, involving discipline, mental rehearsal, sacrifice and goal-setting. Sport and business are similar, he says, in their competitiveness and need for teamwork and planning. But in the end it all boils down to the individual and how much he wants to win. To finish, he recalls the effect of one of those classic one-liners from his old coach Jack Gibson: "Football is the game of life."

The Sterling routine gets a generous response: another win. And he has enjoyed himself. Earlier in the day, he had traversed the 18 holes of Kooralbyn's golf course. Tomorrow he'll go to the races before cranking out another speech at Jupiter's Casino, then back up for another golf date at nearby Royal Pines on Sunday. Not a bad weekend, he reckons - and all expenses paid.

The irony of these few days says much about the man. Football and fun make up the game that is Peter Sterling's life. He admits that it's all just been one big ball, and for years it was to hell with anything that might have stood in the way of that lifestyle. He works bloody hard at his football, has been a model to his peers, and the rewards have followed. Yet he has enjoyed every moment, giving his blood and guts to something he loves to death anyway.

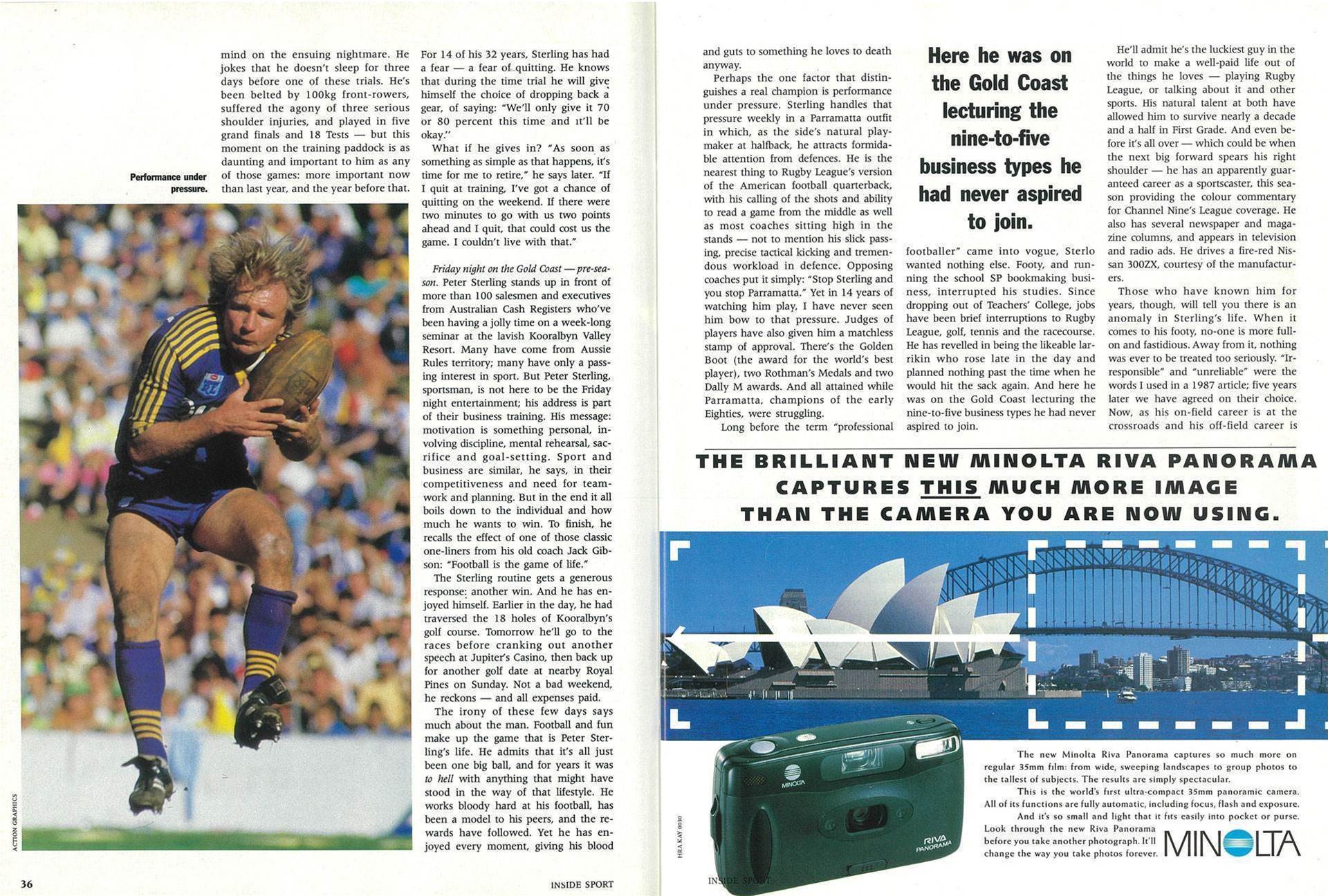

Perhaps the one factor that distinguishes a real champion is performance under pressure. Sterling handles that pressure weekly in a Parramatta outfit in which, as the side's natural playmaker at halfback, he attracts formidable attention from defences. He is the nearest thing to rugby league's version of the American football quarterback, with his calling of the shots and ability to read a game from the middle as well as most coaches sitting high in the stands - not to mention his slick passing, precise tactical kicking and tremendous workload in defence. Opposing coaches put it simply: "Stop Sterling and you stop Parramatta." Yet in 14 years of watching him play, I have never seen him bow to that pressure. Judges of players have also given him a matchless stamp of approval. There's the Golden Boot (the award for the world's best player), two Rothman's Medals and two Dally M awards. And all attained while Parramatta, champions of the early ‘80s, were struggling.

Long before the term "professional footballer" came into vogue, Sterlo wanted nothing else. Footy, and running the school SP bookmaking business, interrupted his studies. Since dropping out of Teachers' College, jobs have been brief interruptions to rugby league, golf, tennis and the racecourse. He has revelled in being the likeable larrikin who rose late in the day and planned nothing past the time when he would hit the sack again. And here he was on the Gold Coast lecturing the nine-to-five business types he had never aspired to join.

He'll admit he's the luckiest guy in the world to make a well-paid life out of the things he loves - playing rugby league, or talking about it and other sports. His natural talent at both have allowed him to survive nearly a decade and a half in first grade. And even before it's all over, which could be when the next big forward spears his right shoulder, he has an apparently guaranteed career as a sportscaster, this season providing the colour commentary for Channel Nine's league coverage. He also has several newspaper and magazine columns, and appears in television and radio ads. He drives a fire-red Nissan 300ZX, courtesy of the manufacturers.

Those who have known him for years, though, will tell you there is an anomaly in Sterling's life. When it comes to his footy, no one is more full on and fastidious. Away from it, nothing was ever to be treated too seriously. "Irresponsible" and "unreliable" were the words I used in a 1987 article; five years later we have agreed on their choice. Now, as his on-field career is at the crossroads and his off-field career is waiting to blossom, he has matured. A year out of the game, public doubts about his future in football, a blossoming relationship with Olympic hockey player Sharon Buchanan that required him to spend a fortune crossing the continent before she moved to Sydney (where was compass then?), an understanding of the need for commitment away from rugby league - all these factors have added wisdom to Sterling's make-up.

The relationship between Peter and Sharon is based largely on mutual respect for each other's devotion to sport. Although Sharon, 28, has been in the national side since she was 16 and is the first Australian woman hockey player to make 150 international appearances, she remains a little-known champion — this despite the Australian hockey side being world champs and winners of Olympic gold. These sportswomen stagger Sterlo with their professionalism.

"The thoroughness of their preparation is amazing," he says. “Before Seoul they went to Darwin to prepare themselves. They played matches against teams wearing the uniforms of their scheduled opponents, had authentic crowd noise over the loudspeakers, and even had the team bus arrive late so they wouldn't panic if it happened in Seoul. Sharon is an incredible competitor and a great athlete. We often train together, but she's much tougher than me. She'll do 30 100-metre sprints without much recovery time; I couldn't do half that."

Sharon has quietly helped create order in Sterlo's life. Little adjustments - like making sure he has a diary next to the phone, and reminding him of appointments. Take-away meals and the local laundromat are things of the past.

Times have changed since the decade when Sterling lived according to daily whims. He can't remember particular instances where he abused commitments for a chance to go to the track or to practise his golf - but he was dumped by radio station 2WS because of his unreliability. He can't say exactly why … but I vaguely recall an unscheduled visit to Grafton for the annual two-day race meeting without asking the boss first. He became first grade captain of Parramatta in 1987, but Peter Wynn was given the club captaincy role for fear of Sterlo forgetting an important engagement. Messengers have often chased him all over golf courses to get his columns in on time.

Lack of punctuality or the failure to keep an appointment must, of course, be kept in perspective. In many other ways Sterling has been a model sportsman in the public eye. His is a clean-cut image with never a whiff of scandal about his private life; most times he is willing to give back to the sport that has brought him fame and reasonable wealth. Hell, he's just a fun-loving guy who occasionally surrendered to his penchant for a good time when everyone wanted a piece of him. But it was annoying.

That's all behind him, he reckons. "I don't consider myself unreliable or irresponsible any more. Maybe I've finally matured. Channel Nine, and Ten before that, offered me something attractive and guided me. I also see things in a different way now. Before, I saw things from a young footballer's point of view. Now I can see things through the eyes of others — including the club which I love greatly. What disappoints me most about those past misdemeanours are the people I let down — people I respected. By not turning up, I failed to show that respect. It was always, ‘They'll understand, they know what I'm like.’ Now I realise that's just not good enough. I do work for 2WS now and I am very conscientious about never letting them down. Maybe I'm looking for redemption."

Sydney Football Stadium, July 9, 1988. Third Test, Australia v Great Britain. Sterling runs from a scrum in the opposition half and steps inside. Leeds second-rower Roy Powell breaks quickly and powers into Sterling on the right side just as another Pom sandwiches him from the left. Together they send him earthbound and, without a free left hand to soften the fall, Sterling lands directly on his right shoulder. It's the end of Sterling's 1988 season and, with his retirement from representative football the next year, his Test career as well. Was this the beginning of the end?

Brookvale Oval, the last game of the 1989 season. It's announced that Peter Sterling will abort his Australian career to play two seasons for Leeds in England. As he runs out in his last match for Parramatta, the Manly ground announcer asks for a salute to the champion from the Manly fans - the Eels' arch-rival club. Less than 15 minutes into the game, as Manly hooker Mal Cochrane is about to kick downfield, Sterling breaks from the ruck to pressure him. Cochrane steps clear, Sterling tumbles into a virtual sand bunker and rips the ligaments from his left ankle. Two days later Sterling is scheduled to fly to England, but the injury will sideline him at least until Christmas — halfway through the English season. He and Leeds decide to call the whole deal off and his biggest career change becomes an about-face. He's back to Parramatta for another season - or three or four.

April 1, 1990, North Sydney Oval. Peter Sterling is fearful he will become an April Fool. His right shoulder has never been 100 percent since the 1988 Test. He's aggravated it during the off-season and is a late starter in the premiership. This match is his long-awaited return. Minutes into the game, he dives into a tackle and emerges gingerly clutching the shoulder. Just a small tear of the ligament, they think, and the Eels' skipper rejoins his mates for most of the rest of the match which, as is becoming familiar, they lose. But further inspection shows that cutting and tying the ligament for the third time won't solve the problem. He needs a complete shoulder reconstruction. 1991 had come and gone in one frustrating match.

Over the ensuing six months, the "experts" will tell Sterling to retire. They're scared that an unsuccessful comeback will taint the memory of a marvellous career that saw him play a major role in the transformation of dead-beat Parramatta into the champions of the ‘80s, and overshadow his achievement in winning every award, team and individual, available to a player. Remember Langlands and the white boots? But never, never did he countenance the idea.

"It seemed to enter everyone else's mind but mine," he says. "The thing is that I believe, even if no one else does, that my best football is still to come. And if I stop believing that, why should I want to keep playing? Overall my game is not much affected by the years except in a good way - the longer I play, the more experienced I get and the better player I become. The nicest thing anyone's said about me was when [Western Suburbs coach] Warren Ryan said that I'm quick between the ears. As long as I don't lose that, I can compete."

If the shoulder packs in on him again, surely that would be the end? "It's not black and white. I'd be guided by medical staff. But I admit that for the first time in my life I'd have to contemplate retirement."

In the months of recuperation, Sterling has had time to study his life. He is something of a philosopher, and a fatalist. But he does realise how different the past three or four years could have been. Let's face it, if not for that day at Brookvale he would have been in England now – and may never have met Sharon. If not for that Roy Powell tackle he would not be confronting his third comeback. If not for the recurrence at North Sydney and the wasted year, he would not have had to contemplate so much of his life away from the game. He knows that this year could well be the most important of his life.

Back at Parramatta Stadium, the unrelenting Rowland Smith says Sterling has never done better times in the much-maligned time trials. He has no fear of the man capitulating. "I've been at Parramatta nine years and I've never seen him quit at anything. If he had two broken legs he wouldn't quit. He's never been keener or trained harder than since he's come back from the shoulder injury. It's as if he wants to prove something to those people stupid enough to write him off. I know Sterlo has a laidback attitude to life, but when it comes to rugby league, no one works harder, even though he is such a natural. And off the field, too, I've noticed he's finally grown up."

Max Sterling, who became more of a friend than an iron-fisted father after the death of his wife when Peter was nine, also sees the changes in his only son following the Sharon Buchanan connection. "About two years ago," Max recalls. "I said to his sister Chris how anaemic and scrawny he looked - as if he wasn't looking after himself. Now he's great - looks strong, is so keen and happy. Like a new bloke."

As he nears his 33rd year, Sterling's mind is utterly focused on redeeming himself. As a player, as a media man, and as a man with more commitments in life than he's ever had to face.

Related Articles

Viva Las Vegas: Join Golf Australia magazine's Matt Cleary on a golf and rugby league spectacular

19 Holes With ... Chad Townsend and Val Holmes