Lewis Hamilton, the overnight success that took eight years to be realised.

IT WAS THE MOMENT that was supposed to be the breaking of Lewis Hamilton. On the second lap of last year’s Belgian Formula One Grand Prix at the venerable Spa-Francorchamps circuit, Mercedes’ Nico Rosberg committed one of motorsport’s cardinal sins – thy shall not crash into thy team-mate – when he ran into the back of Hamilton as the pair squabbled over the lead. Rosberg’s front wing damage was minimal; Hamilton’s left rear tyre was shredded. As he limped back to the pits for new rubber, Hamilton’s championship quest looked done. By the end of the race, where Rosberg recovered to finish second behind Daniel Ricciardo while Hamilton sulked into retirement, Rosberg’s championship advantage over Hamilton had blown out to a season-high 29 points, more than a race win.

Then Rosberg went for the jugular.

Both drivers were summoned to a post-race meeting with Mercedes’ furious management, Rosberg putting his hand up to take blame for the clash, but using his admission to twist the knife further. Sensing his team-mate being sucked into an emotional maelstrom, Rosberg chose to play Hamilton like a puppet. As soon as the meeting finished, Hamilton hurriedly left the Mercedes motorhome, running headlong into a heaving press pack expectant for answers.

“He basically said he did it on purpose,” an agitated Hamilton blurted. “He said he could have avoided it, but he didn’t want to. He basically said, ‘I did it to prove a point.’”

Long-time Hamilton-watchers braced themselves for the fallout. He is emotional and reactionary at the best of times, but Rosberg’s words – true or not – had the potential to send Hamilton off the deep end. But a funny thing happened on the way to his implosion. First he got mad – “I’m going to have to turn this up; this means war,” was his comment afterwards. Then he got away, decamping to Sardinia with friends while shutting the world out. And then he got even, winning six of the final seven races of the year after Belgium to leave Rosberg – and the rest of the field – choking on his exhaust fumes as he became Formula One world champion. It was a turn of events that was as impressive as it was unlikely.

Hamilton’s 2014 title was the second F1 crown his sheer talent suggested would come; the journey from his first in 2008 explained why there were doubts that talent would ever reap the ultimate reward again. British drivers have their fingerprints all over Formula One’s history books, but just four – Sir Jackie Stewart, Jim Clark, Graham Hill and now Hamilton – have won multiple championships. It is an elite group that passes as motorsport royalty, but the circuitous path Hamilton has taken to join it might just redefine the limits of what he could achieve by the time he’s done.

******

In many ways, Hamilton is an overnight success that took eight years to be realised. In 2007, the 22-year-old kicked off his F1 career in Australia in audacious fashion, sweeping past McLaren team-mate and reigning world champion Fernando Alonso at the first corner in Melbourne, en route to finishing on the podium in his F1 debut. He placed second in the next four races, then took his first Grand Prix win in Canada. In just six races he’d exceeded the considerable hype that had followed him from his junior karting days. Inter-team politics with Alonso and McLaren’s futile attempts to control their drivers saw Ferrari’s Kimi Raikkonen steal the 2007 title from Hamilton by a single point in the final race in Brazil. A year later, the same venue played host to arguably the most dramatic title-decider in F1 history, Hamilton taking fifth place on the final corner of the final lap of the final race of the year to score enough points to edge Ferrari’s Felipe Massa for the crown.

Greatness seemingly beckoned, but Hamilton soon became stuck in neutral. He won races in subsequent years, but only once, in 2010, did he figure in the championship picture late in the season. He was good enough to win races with sheer ability, but his enjoyment of the fame, fortune and celebrity trappings of being one of world sport’s most recognisable stars raised questions about his commitment. And then there was the matter of being in the right place at the wrong time. Timing, especially in an environment as unrelenting as Formula One, is everything – and until 2012, Hamilton’s was mostly bad.

When Hamilton won his second Grand Prix at Indianapolis in his rookie season of 2007, a floppy-haired German named Sebastian Vettel made his debut for BMW-Sauber as a fill-in for the injured Robert Kubica, and turned heads as he finished eighth to become the youngest pointscorer in F1 history at just 19. While Vettel marked himself as someone to watch for the future, the present was clearly all about Hamilton. But it wasn’t long before things changed. While Hamilton was living the F1 life, Vettel was emerging as a force. With his childhood hero Michael Schumacher acting as an unofficial mentor, Vettel worked on emulating his compatriot’s razor-sharp technical mind, minimising mistakes to metronomically churn out optimum laps, and largely keeping his own counsel between races, retreating to rural Switzerland with his childhood sweetheart and offering little of himself to the outside world. It was a combination of skill, devotion and discipline that proved to be devastating. When Red Bull Racing produced a car capable of running towards the front in 2009, Vettel won races. Second in that year’s championship, he took off in 2010, taking his first title by a whisker before streeting the field a year later. And in 2012, the German was the immediate beneficiary of a set of circumstances that turned Hamilton’s career around.

******

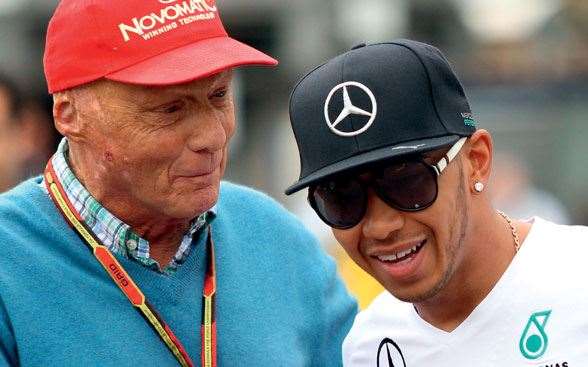

With his body still showing the scars of the 1976 German Grand Prix accident that nearly killed him, and his trademark red cap, three-time F1 world champion Niki Lauda stands out in a crowd at any time, but the loquacious Austrian was trying to be as anonymous as possible as he strode through a Singapore hotel lobby in the wee hours of a September Sunday morning in 2012. Qualifying for the night race around the city’s floodlit streets had taken place a few hours before, and Hamilton had planted his McLaren on pole with a mesmerising lap that showcased his brilliance on street circuits. Now, as the clock ticked past 3am, Lauda tapped on Hamilton’s hotel room door for a clandestine meeting. As non-executive director of Mercedes, Lauda needed a replacement for Michael Schumacher, who was doing little more than making up the numbers at the age of 43. As unlikely as it sounded, might Hamilton be the man to step into the cockpit vacated by the most successful F1 driver of all?

“I remember the discussion because he was on pole position with McLaren; he was basically winning everything and I asked him, ‘Would you consider going over to Mercedes?’” Lauda later recalled. “He said, ‘Why should I go? This car is winning, all I want to do is win, and your car is not winning.’ I said, ‘Shit, he’s right.’”

But fate was to play its hand. The next night, Hamilton made a strong start from pole and was cruising towards victory when the gearbox in his McLaren broke, gifting Vettel a win that should’ve been his. It was Hamilton’s third non-finish in five races. He fell 52 points behind Ferrari’s Alonso in the title race, his hopes of that elusive second crown dashed again. That night, Lauda revisited Hamilton to ask the same question. Just five days after the Singapore race, Hamilton stunned the F1 world by dumping McLaren, a proven race-winner, for Mercedes, which had won just a single Grand Prix since 2010. The numbers were mind-boggling – a reported $100 million salary for three years.

It was a huge risk for Hamilton, one that seemed impulsive on the surface, but perhaps a decision that wasn’t a surprise given the way his career had evolved. From the moment he’d approached McLaren team boss Ron Dennis at a motorsport awards night at the age of ten, and told Dennis he’d like to drive for his team one day, Hamilton’s career had been intertwined with the British powerhouse team. Dennis was intrigued by Hamilton’s talent, not to mention the marketability of employing the sport’s first black driver. As Hamilton rose through the ranks with McLaren’s support, Dennis became an enormous influence in Hamilton’s life. It was a strong bond. When Alonso approached Dennis in the fractious 2007 season to demand he be made the priority in the team over Hamilton as tensions between the drivers rose, Dennis didn’t budge, backing the rookie in whom he’d invested so much. At the end of the season, Alonso left for Renault, and at 23, McLaren was now Hamilton’s team.

After Hamilton’s 2008 title, Dennis stepped sideways from the McLaren team principal role in April the following year, and the peaks and troughs of Hamilton’s results, not coincidentally, became more dramatic. Hamilton’s father, Anthony, who had juggled multiple jobs to fund his son’s earliest karting days, acted as Lewis’ manager until 2010, when he was abruptly cut loose in favour of the XIX agency run by former Spice Girls manager Simon Fuller, which counted David Beckham and Andy Murray amongst its clientele. With seismic changes off-track, Hamilton’s efforts on it continued to confound. The 2011-12 seasons were punctuated by several spellbinding performances that resulted in wins, and occasionally questionable decisions that seemed more bone-headed than the one preceding it.

In Canada in 2011, Hamilton needlessly crashed with team-mate Jenson Button in the early laps in a clash that was slammed by the sport’s insiders. That same weekend, Hamilton invited his friend, the rapper Ice-T, into the McLaren garage, his guest recording a home movie that became a profanity-laden YouTube must-see, much to McLaren’s deep embarrassment. In Belgium in 2012, Hamilton tweeted top-secret team telemetry as a petulant response to being out-qualified by Button, which was gleefully gobbled up by gobsmacked engineers at rival teams. Two races after that came Singapore, that broken gearbox, and Lauda’s late-night shot in the dark that hit the target.

Hamilton revelled in the new-found freedom of being his own man in an unfamiliar environment at Mercedes, and a side to him that had been muted by McLaren’s corporate stuffiness began to emerge in 2013. Tattoos sprouted on seemingly every available patch of skin. A $35 million private plane was purchased to jet back and forth to Los Angeles to be with on-again, off-again girlfriend, Pussycat Dolls singer Nicole Scherzinger. The letters H-A-M, urban slang for “hard as a motherfucker”, appeared on his crash helmet. The oversized gold chains and insistence on bringing bulldog Roscoe to race weekends completed the picture. Quite what the fastidious Dennis thought of his former driver bringing a pet with its own Twitter handle to the track can only be imagined …

******

While Hamilton looked more comfortable in his own skin after joining Mercedes, the move, early on, seemed ill-timed. In 2013, Hamilton had the most barren season of his career, winning just once, as Sebastian Vettel’s four-year reign reached its zenith with 13 victories, including the last nine Grands Prix of the year.

Hamilton was nowhere in his first season for Mercedes, finishing fourth in the championship, with less than half of Vettel’s record 397-point haul. But behind the scenes, Mercedes was working feverishly to shake up the sport’s pecking order; the biggest regulatory revolution in three decades was scheduled for 2014, and the German automotive giant had been hatching a three-year plan to be ready for F1’s brave new world.

That era debuted in Melbourne last March to lukewarm reviews; the rib-clattering shriek of the sport’s signature V8 tune had been muted by the change to V6 turbos, changes to the front nose regulations left the cars looking disturbingly phallic, and with cars restricted to 100kg of fuel, F1 was criticised for becoming a glorified economy run on fragile Pirelli tyres rather than the flat-out, hairy-chested blast its fans had become accustomed to. The difference in lap times to the previous year in the early races, and the reduced sensory overload offered by the new machines, was the source of much amusement to the critics, but nobody was laughing at Mercedes, who had focused its considerable resources on producing a car that redefined dominance. Of 19 races last year, Mercedes won 16. Only Ricciardo’s three victories stopped a complete whitewash, and they were aided to some degree by rare Mercedes’ misfortunes or unreliability.

This wasn’t Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost at McLaren in 1988, Schumacher running red rings around the rest in the early 2000s, or Vettel’s Red Bull rush in 2013; this was better, the most dominant season by one team in F1 history. Every pole position bar one, and 11 one-two finishes, turned the sport upside-down.

With the championship quickly turning into a two-horse race and Mercedes sticking with a pre-season pact not to impose team orders on its drivers, Rosberg saw the chance to nab a title that history suggested was beyond him. While he overshadowed Schumacher over their three-year stint together at Mercedes from 2010, that was a 40-something Schumacher far removed from his Ferrari pomp. Hamilton had Rosberg covered in their first year as team-mates in 2013, but with a championship-winning car at his disposal, Rosberg raised his game – and his gamesmanship – to new levels.

The concept of “team-mates” in Formula One is one of the great misnomers in sport; feuds between the likes of Senna and Prost, Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet at Williams, and Vettel and Mark Webber at Red Bull can see drivers hell-bent on beating the man on the other side of the garage more than anyone else on the grid. Rosberg knew Hamilton well – they’d been karting team-mates as kids – and used that knowledge of Hamilton’s instinctively emotional response to adversity to fire a psychological volley across Hamilton’s bows in Monaco.

In qualifying on the twisty streets of Monte Carlo, Rosberg had the better of Hamilton in a shootout for pole that all but guarantees a race win on a circuit where overtaking is close to impossible; with his name atop the timesheets but Hamilton behind him on-circuit and on a faster lap, Rosberg, at first glance at least, clumsily out-braked himself into the tight right-hander at Mirabeau, sailing down the escape road before reversing back towards the circuit. With a car off track and in a dangerous positon, the trackside marshals had little choice but to neutralise the corner by waving yellow flags, meaning all drivers behind Rosberg – including Hamilton – were forced to back off, their chances at pole ruined. Hamilton smelled a rat and was apoplectic afterwards; Rosberg donned his best poker face and tried to sound contrite for his “mistake”. When he won the race the next day ahead of Hamilton, the Briton’s rage only grew.

Rosberg’s victory snapped a four-race run of Hamilton wins, saw him regain the championship lead, and sent Hamilton into a tailspin that saw him win just one of the next six Grands Prix. Then came Belgium and that clash that threatened to change the shape of the title race; unfortunately for Rosberg, the change wasn’t the one he wanted. With every chance of capitulating, Hamilton did the exact opposite.

At the next race in Italy, Hamilton recovered from a poor start to harry Rosberg into two mistakes under braking at the first corner, capitalising on the second of them to take a lead he wouldn’t relinquish. Engine software issues ended Rosberg’s hopes in Singapore, Hamilton swept past his team-mate for the lead in a downpour in Japan, won convincingly in Russia, and stalked Rosberg again in the United States, again making the most of a Rosberg error under pressure to take the lead and win his fifth-straight race. Rosberg ensured the title fight would go down to the controversial double-points decider in Abu Dhabi by edging Hamilton in the penultimate race in Brazil, but Hamilton made a brilliant start in the UAE finale to blast past his team-mate into the first turn and take an 11th win for the year – one that secured the crown. From the lowest of lows, Hamilton’s steel after his declaration of “war” impressed as much as his speed.

******

With a second title in his keeping, what might Hamilton’s ceiling be? He is now 30, an old-timer on the grid compared to the likes of 17-year-old debutant Max Verstappen at Toro Rosso, and the man who replaced Vettel at Red Bull in the off-season, pimply faced 20-year-old Russian Daniil Kvyat. But the all-action driving style that has been the bedrock of his career from his earliest days remains.

The body language of a Mercedes being bossed by Hamilton is different to every other car on the grid, a flurry of reflexive hand movements on the steering wheel dealing with any instability at the rear of the car as it temporarily breaks traction in the corners. Add to that his improved and under-rated ability to manage tyre usage and fuel consumption, and you have – when motivated and the stars in his life off the track are aligned – a world-beater. Hamilton lacks Vettel’s Teutonic consistency, Alonso’s sheer bloody-mindedness to bend a car to his will, and Ricciardo’s laser-like ability to spot a gap and mug an unsuspecting rival into a corner. When the Hamilton emotional rollercoaster bottoms out, he’s prone to lapses of judgement, pursuing car set-up options that leave him lost, making questionable decisions in wheel-to-wheel combat. But his high points are so high that they’re worth the wait. Just four drivers in F1 history – Schumacher (91), Prost (51), Senna (41) and Vettel (39) have more victories than Hamilton’s 33; no less of a judge than Sir Stirling Moss believes Hamilton could wind up with six world titles, while Mansell, always economical with his praise, says Prost’s win tally is comfortably within reach.

He’s not everyone’s cup of tea – elements of the British press moaned about the globetrotting Hamilton not paying tax in the UK late last year, a criticism that wasn’t levelled at compatriot Button after his world title in 2009 – but there’s no denying Hamilton’s results, nor his quality.

The 2015 season, which again starts in Melbourne, comes after an off-season that turned what was a stable driver market on its head. Hamilton, Vettel and Alonso are thought by most astute judges to be Formula One’s three kingpins; that two of them – Vettel to Ferrari, Alonso back to McLaren – have changed colours for 2015 says much for the chaos behind the scenes that was a direct result of Mercedes’ dominance last season. With so much change in the driver ranks but very little in the sport’s technical and sporting regulations, stability and continuity will be more critical than ever. While they’re two words you wouldn’t usually associate with the reigning world champion, the 2015 version of Hamilton is clearly a different animal.

He’s already won more races than any British driver in F1 history; joining Stewart with three titles at the end of 2015 is a goal very much within reach. It won’t be smooth sailing, without drama and free of twists and turns – nothing with Hamilton ever is – but it is very probable, and it will be compelling. As the past eight years have shown, Hamilton knows no other way.

- Matthew Clayton

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.jpg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)