The modern method of delivering a ball probably saved game from extinction.

Every sport evolves according to some requirement: force of logic, convenience, the iron imperatives of technological advancement, the whims of serendipity.

The origin of overarm bowling is uncertain, but one thing is sure: it was the most fortunate of all developments in cricket’s evolution. Its adoption was a triumph of foresight over stubborn bureaucratic inaction, and because of it, cricket survived.

Why was it so important? Even the battiest of cricket fanatics could tell you that. Contemplate the unimaginable for a moment: envisage the persistence of cricket played with underarm bowlers, and you’d see something perhaps akin to royal tennis, which happens to occupy an arcane corner in the same universe as its evolved variety. But royal tennis enjoys a certain viability. Underarm cricket would suffer in comparison with its advanced version. You’d see a sport played not in today’s revered arenas, but on sequestered English lawns. You’d hear not the thunder of multitudes but isolated shouts of “mind the divots!”, “bravo – well hit, Fotherington-Smythe!” and “huzzah – the cucumber sandwiches have arrived!” You’d see a game in which bowling overarm, and above a certain pace – even imparting too much turn – is simply not cricket, chap! If the colonies retained this pursuit at all, you’d be talking in hushed tones (in libraries) of the Pastor Blaster, the Ill-tempered Alley Cat of Lahore or Fred “the rather horrid” Spofforth ...

And of course no one would be covering it, save the odd report in Masonic News or The Royal Gazette.

Certain stories around the introduction of overarm bowling are possibly apocryphal. One thing we can state with conviction: early attempts would’ve been given the same treatment Bradman gave the prospect of increased pay; the ACB and ABC gave Packer; English teams gave talk of going all-out to win Test matches in the 1950s. Left to its own devices, cricket would’ve perished long ago. Remember, even the first googly was considered cheating.

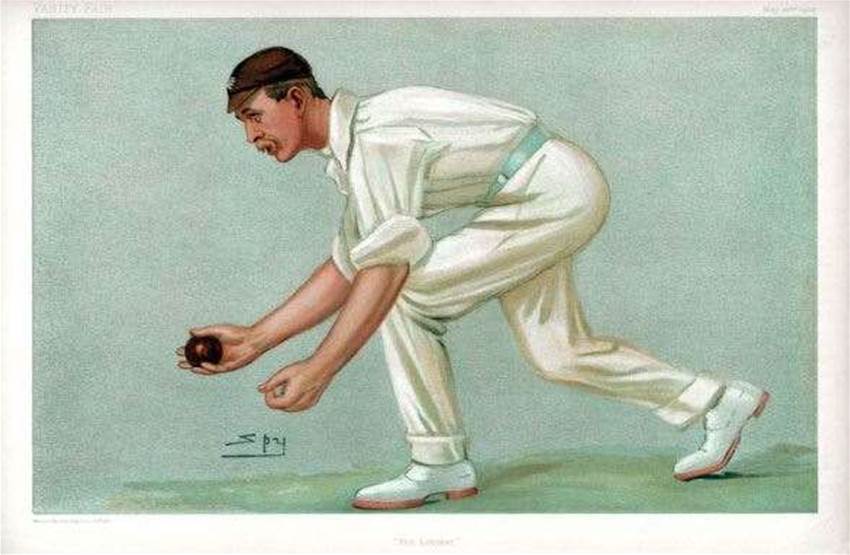

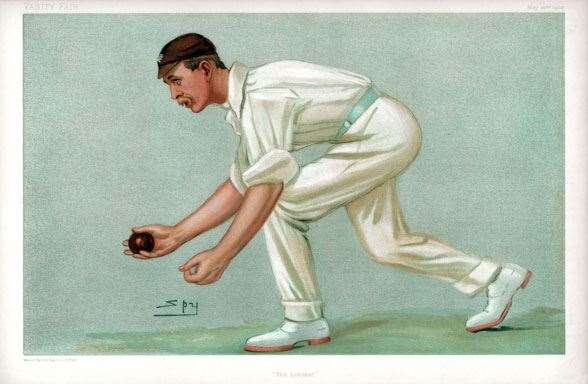

The last of the famous “lob bowling” legends were George Simpson-Hayward and Digby Jephson (pictured). Look, they were good at what they did, no doubt, but from today’s standpoint, the greatest exponent of underarm bowling is something like the bloke who can whisper “Nessun Dorma” the loudest. The game was never going to be considered an athletic pursuit of any sort as long as they delivered the ball the way they did. French cricket would’ve become its most extreme manifestation.

A story has done the rounds – serendipity moves in strange ways – that the first coy move toward bringing the arm above the waist (but not the shoulder) had its genesis during a game of backyard cricket in the early 19th century, when one John Willes, a Kent cricketer, was having a bit of a hit around with his sister Christina. Christina was bedizened in her finest finery just for the occasion, but the great frothing bustles of her dress hindered underarm delivery. This brought her arm outward. It’s doubtful his sister’s roundarm action would’ve conjured visions of lithe thunder-chuckers of the future in Willes’ mind. What he did see, however, was another way of getting one over batsmen, who dominated the game, rather than relying on some helpful caprice of pitch or weather.

There had in fact been earlier controversy about roundarm bowling insinuating its way into cricket, and the action had been banned. Now Willes decided to become its champion. He became, in fact, first martyr to the cause. Four years after he (literally) got on his horse and rode away from the game after being no-balled in 1822, the “roundarm era” was led by Sussex’s William Lillywhite and James Broadbridge, whose increasing success troubled the establishment, which of course got the sympathy of batsmen of the day. By 1835, however, ye olde MCC relented and legalised Lillywhite’s method.

It wasn’t long before the action became more perpendicular, as bowlers noticed overarm bowling seemed suited to a greater variety of deliveries, conveyed with more power, control and subtlety. At first, the ball delivered with the arm above the shoulder was considered a no-ball, but in 1845 the law was altered so this judgement would be left entirely to the umpire. This could easily have been disastrous, but tacit agreement developed over time amongst officials. Lillywhite became a prolific wicket-taker until he was 60.

Certain elements in cricket, some influential, still disputed the action, however. What really established it was a “crisis” which was in all likelihood a conspiracy to have it approved once-and-for-all. This involved Lillywhite’s son. In 1862, when Surrey played All-England, umpire John Lillywhite no-balled Edgar Willsher, who was bowling overarm. The bowler and eight team-mates walked off; play was abandoned for the day. When it resumed, the villainous Lillywhite “diplomatically” stood down. The new umpire allowed play to continue without incident.

Heads spinning in their reforming haste, the MCC drafted Law 10 over a year later. This allowed the bowler to bring his arm over as long it was straight, the action smooth.

After three centuries of birth pangs, the modern game of cricket had at last been safely delivered.

‒ Robert Drane

Related Articles

Luck of the Draw

Harman hails lookalike Ponting as 'handsome fella'

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)