Modern professional football's crackdown on the "biff" had to happen. This ain't 1981 anymore ...

Last year, after NSW captain Paul Gallen caused disgust and uproar by king-hitting Nate Myles in front of millions of viewers in State of Origin I, the NRL decreed that any punch was a sin-bin offence. In light of the spate of “coward punches” and subsequent murder charges on the streets of Sydney, the concept of professional athletes managing to control their tempers and keep their fists to themselves during competition shouldn’t have been too much of a stretch in this modern era – and an important step up for the code. There were howls of disapproval that the game was going soft … but guess what? It hasn’t. And as we go to press, we can say that Gallen’s was the punch that dragged rugby league into the 21st century: there's not been a single sin-binning for this offence all season. Let there be no more argument. It had to happen.

Sydney Cricket Ground, 1981. The Newtown Jets vs Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles elimination semi-final is two minutes old when the game’s first scrum erupts into what will forever be referred to as the ugliest all-in brawl in Australian top-grade rugby league. “We didn’t speak about putting the blue on, but the blue happened because of me and Manly and what we were about,” Jets’ then-halfback Tommy Raudonikis would remember later in an interview for a video clip celebrating the sport’s centenary in 2008. “Mark Broadhurst clashed with Steve Bowden after the scrum, who gave Broadhurst the two best head-butts you’ve ever seen,” the feisty stalwart remembered.

Legendary TV commentator Rex Mossop’s call of the all-in brawl sounds like he’s describing a boxing bout rather than a ball sport: “There are three separate groups fighting. Broadhurst handling Bowden, Bowden a left. They’re going about it hammer and tong – like two heavyweight fighters, these two. And on the quarter line, another melee, five or six involved ... What’s going to be the upshot of all this? Is it going to be a scrum, a penalty? It’s a penalty to Newtown ... Well, I don’t know how he gets a penalty out of that lot. And I’ll never know.”

Manly prop Broadhurst ends up with, according to Mossop, “two black eyes, by the look of it”, while Newtown front-rower Bowden and Manly’s Terry Randall are marched off by referee John Gocher for head-butting and kneeing respectively.

Just as cultural, political and sporting figures grow in legend year by year (Ned Kelly, Don Bradman etc.) so too the Newtown/Manly “all-in” will be ever-uglier as the decades tick over. Today, many of us watch this and similar incidents from Australian footy’s (pick your code) 1960s, ’70s and ’80s with a heightened awareness of what physical damage and psychological trauma a punch to the head can cause. Some of us shudder, but there are many who miss the days of landing on the couch, beer in hand and witnessing not just athletic freaks of nature, but some of the gnarliest, toughest men ever to lift their knuckles off the ground.

There will never be another John “Dallas” Donnelly, the Wests Magpies’ larrikin of the ’70s and ’80s who became edgy (epileptic fits and all) whenever he skipped his medication. Likewise, the mould was broken when Leigh Matthews – Hawthorn’s tough, ruthless and physically unparalleled brute of the late ’60s to the mid-’80s – entered the world. People went to the footy to see these guys hurt the same way petrol heads flock to speedways to watch the shrapnel-spreading demolition derby.

Today, it’s important to consider the legalities of delivering people what they paid for (chaotic violence at $36 a ticket) in the sphere of the law of the outside world. Many think law-enforcement stops at the turnstiles, with whatever happening on the field long-forgotten when that first stubby (or these days lolly snake) is consumed after the siren. But the law is everywhere, keeping an eye on everyone, whether they’re the star halfback landing a get-square for that earlier love tap, or some drunk fan ready to hurdle the fence and throttle the opposing full-forward because he hates his guts.

The jury is still out on whether everyone is convinced that this violent, punch-happy era disappeared for good. When the NRL last year banned punches forever, plenty of fans and players vented their frustration on social media and the various footy discussion panels, proclaiming the authorities were taking the “manliness” out of the game, and that “they’re trying to turn the game into netball”. Really? If this is what netball is like, we’re getting tickets ...

THE LAW

Princes Park, 1985. Final term. Hawthorn ahead 115-88 over Geelong. The combatants are about to become involved in one of the ugliest incidents in top-level Australian rules history. On one of those days where the players seem more interested in stirring rather than outplaying one another, you can cut the niggle in the air with a chainsaw. With three Geelong troops already on report for misconduct, Mark “Jacko” Jackson, returning to terra firma after taking a mark, is struck across the top of the face by Hawthorn’s Gary Ayres. Jacko retaliates (he’s been in a goading mood himself all day), whacking Ayres on the nose. A clumsy melee breaks out; jerseys are grabbed and players on both sides are knocked and wrestled to the ground.

After a few more stoppages for silly roughhousing, the ball makes its way deep into Geelong's territory, then back up towards the centre of the field. Twenty metres off the play, Hawks stalwart Leigh Matthews king hits Geelong’s blond-locked Neville Bruns across the head with a stiff arm, the Cats’ rover unaware what was coming (silly fellah had his eyes directed towards the play).

After copping a broken nose and concussion caused by a vengeful Steven Hocking strike, Matthews is led from the ground, his melon covered in claret, a charging Jacko bounding his way over to give him a verbal send-off. Bruns is being supported by trainers Weekend At Bernie’s-style, his head collapsing backwards again and again as if his character’s puppeteer is distracted.

It was revealed later that Bruns had suffered a broken jaw. After being charged by the VFL commission, Matthews had his playing permit cancelled for a month. The Hawthorn skipper was also charged by police and fined $1000, later reduced to a 12-month good behaviour bond on an assault charge.

The Matthews/Bruns incident resulted in much debate over the role of the law in sporting incidents, actually raising more questions than it answered, such as: what role does the law play in sports violence? When does “whatever happens on the field, stays on the field” not apply? And: could the law (specifically police) ever intervene mid-match where officials have lost control?

Sport and the law have danced numerous times during many of our readership’s careers in either playing or watching our favourite footballs. You may recall the Wests Tigers’ Jarrod McCracken successfully suing the Storm and two of its players, Marcus Bai and Stephen Kearney, over a spear tackle in 2000 which ended McCracken’s career. Cronulla's Steve Rogers sued the Bulldogs’ Mark Bugden over a swinging arm in a 1985 match that broke Rogers’ jaw. And in 1999, Tigers’ legendary fullback Garry Jack took legal action against hardman Ian Roberts over a fight in a Balmain-Manly match in 1991. More gruesome stories abound in other codes, such as the tragic case of Riaan Loots, a rugby union player in South Africa who died after sustaining injuries during a match. Loots, 24, was felled by a stiff arm and then kicked in the head during an ill-tempered game between his team, Rawsonville, and the Delicious club of Ceres. He died in hospital two days later. Delicious’ Benjamin Zimri, who was convicted of culpable homicide for assaulting Loots during the 2006 match, was finally told he had to serve jail time after a full bench of the Western Cape High Court dismissed his appeal only last year.

Deborah Healey is an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of New South Wales, where she teaches and researches on issues relating to competition law and commercial aspects of sport and law. Her 2009 book, the fourth edition of Sport And The Law, discusses issues concerning the legalities of heavy physical contact sports. “Those in sport should not assume they’re immune from prosecution just because a particular incident takes place in a ‘game’,” Sport And The Law states. “In the area of assault, context is everything. A very minor contact, causing no physical injury, may constitute an assault if the actor possesses a certain state of mind [such as intention to frighten]. On the other hand, injury [even serious injury] may be caused without the actor being criminally liable. For example, where the injury is caused ‘accidentally’, or where the ‘victim’ has validly consented to the contact, such as in the course of a sporting contest.”

The elite professional stage isn’t the only arena where the law has had to intervene in cases of physical assault on the playing field. In the amateur realm, which more often than not involves younger athletes, assault cases may not just involve participants in a match, but also parents and spectators who have much easier access to the playing area than onlookers at a pro-level venue.

One example of an horrific all-in brawl was the fight which took place last year at the end of the Penrith District Junior Rugby League Under-19s match between the Penrith Waratahs and Western City Tigers at Turnbull Oval, North Richmond. Up to 40 players and spectators were involved in the brawl. Eight players were eventually suspended by the PDJRL, ranging from six-game suspensions to 25 years for their parts in the brawl (all suspended players were from the Western City Tigers club). Two teenagers received 20-year bans; one of them was photographed by the print media at the time with his foot in the air in a stomping pose above the head of the player who kicked the winning penalty goal in extra-time to win the match. This victim took civil action, with this assailant charged with assault occasioning actual bodily harm. His matter was heard by Magistrate Joanne Keogh at the Children’s Crime Court in Parramatta in May this year. A minor at the time of the incident, he pleaded guilty and escaped with a six-month good-behaviour bond. According to Sport And The Law, the type of assault where a player hits another out of frustration or anger must be contrasted with the type of assault caused by forceful play. The first type is no different from an assault occurring anywhere else, and will be treated as such by the courts.

THE PLAYERS

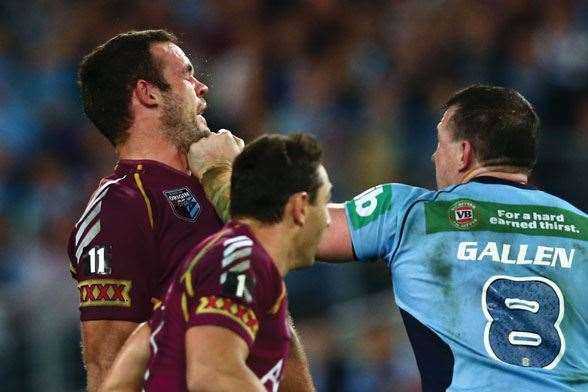

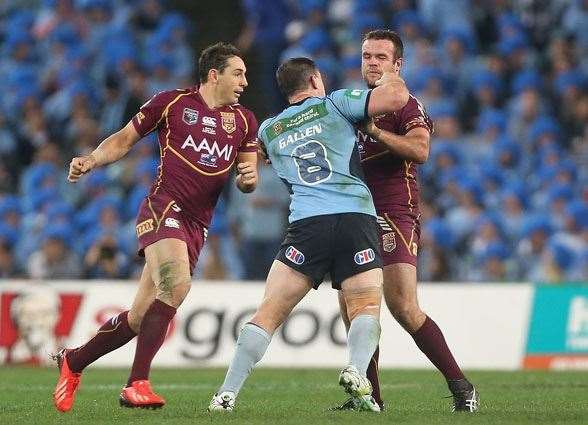

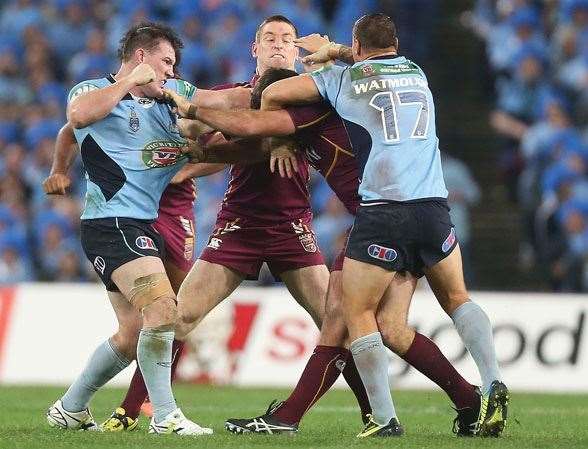

Stadium Australia, 2013. State Of Origin I. Thirty seconds before half-time, New South Wales holds a handy 14-0 advantage. Of all the punches ever thrown in rugby league over the years, tonight’s crowd is about to witness one of the last. Queensland backrower Nate Myles carts the ball forward before being halted by Anthony Watmough and Luke Lewis. Their skipper Paul Gallen is third man in, “helping” with a heavy swinging arm/hidden upper cut to Myles’ head. On the ground with Myles and on his way out of the tackle, Gallen applies his elbow to the face and throat of the second rower none-too subtly, which Myles thanks him for with a solid push after he climbs to his feet to play the ball. The play having moved on, Gallen responds with two solid punches to Myles’ head: a heavy left to his jaw and a right to the cheek which would’ve felled a drunken George Street-reveller, but not Queensland’s toughest staffer, who stands stunned for a few seconds before throwing some back Gallen’s way.

Gallen was livid about the one-match ban he received over the incident, airing his grievance that of all the fights to have marred Origin’s often-violent history, his particular sequence of blows on Myles was the one the league had chosen to finally make an example of. A few weeks later, the game’s authorities announced a strict no-punch stance (applying to NRL weekly matches as well as Origin) that would result in perpetrators being sent to the sin-bin for ten minutes whatever the circumstances. With the threat of a judiciary charge thrown in on top of that, players have been fist-shy ever since, with Gallen's Blues team-mate, Trent Merrin (Origin II, 2013) the only player to be sin-binned for punching since “Gallen Gate”.

The NRL's announcement last year met – and is still meeting – much opposition, the strongest reaction ironically coming from the group standing to benefit the most from the commonsense safety measures, the players. Veteran enforcer Willie Mason argues that cracking down on punching will only increase the niggle: stray elbows and the like. The Newcastle Knights forward told Fox Sports’ panel show, NRL 360, that he “didn’t really enjoy watching Origin II” [this year].

“The niggle has sort've slowed the game down a bit,” he said. “All this stuff, it turns it into AFL.”

We'd buy tickets to that, too.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)