Will the game ever encounter a man like him again?

Never before had cricket encountered a man who thought about the game the way Richie Benaud did ... Will it ever again?

Richie Benaud? Innovator?” anyone from Gen X onwards might ask. “The cricket commentator? Best known to non-cricket people by his alter-ego, Billy Birmingham? Chew for chwenty chew and all that?”

For those who witnessed his days as an outstanding – at times match and series-winning – all-rounder, the assumption that the way people play Test cricket today can be attributed largely to the influence of Richie Benaud is reasonable. First as a player, then as arguably the most accomplished captain the Australian cricket team ever had, Benaud ushered in a revolution of cricket consciousness in three phases.

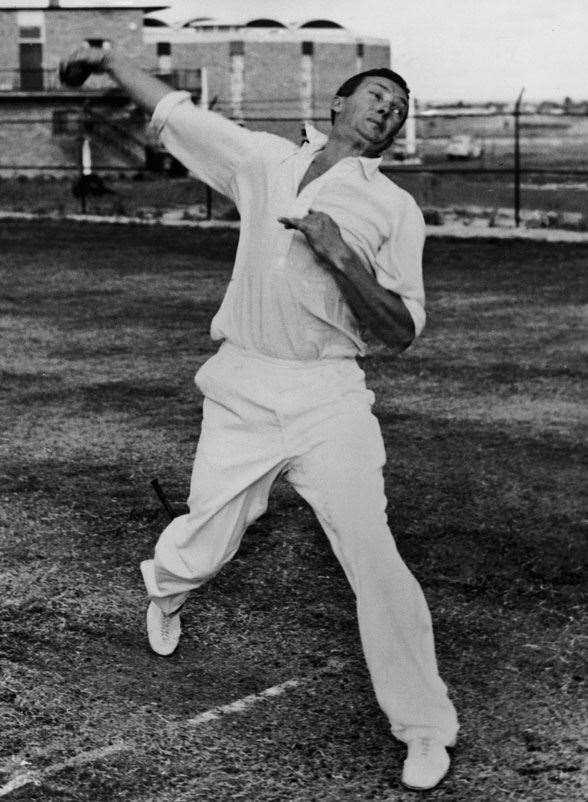

In the first, he was a “rebel” just by virtue of his enthusiasm, his dashing persona, shirt unbuttoned to chest adorned with pendant, collar upturned. Every wicket he celebrated joyously, never disrespectfully. As a tactful, quiet revolutionary, he’d be as unique today as he was then. More so. There’s no such creature in most areas of life.

In phase two, he was Australia’s captain, and introduced a bright era of positive leadership, never losing a series. There was never talk of “mental disintegration”. He no doubt allowed for clever sledging, related to happenings on the field as they unfolded. But he demonstrated – a lesson that should be taken on board today – that a winning disposition needn’t be confused with “killer instinct”. He was the inspiration for another – more forthright – revolutionary, Ian Chappell.

Then came the West Indian tour of Australia, 1960-61. Motivated by love for the game, acutely aware of the opportunity he’d been given to free cricket from the dead hand of the 1950s, he made a contract with West Indian skipper, Frank Worrell, to bring crowds back with exciting, progressive cricket. His Caribbean counterpart was only too willing to collaborate, and together they steered their sides through one of the most exhilarating series ever played up to that time, in front of record crowds. It felt like a revolution; a paradigm shift. It was the first real break from the notion that the Ashes was cricket’s apogee. The tied Test in Brisbane was the perfect dawn, brought about by Benaud’s resolve to snatch an unlikely victory even if the attempt failed.

It didn’t end for Richie when he handed the captaincy to Bob Simpson in 1963-64. As a player, he’d used his skill as a trained journalist to bring the public closer, interviewing opposing players and his own for newspaper columns and books. His account of the tied Test is still one of the best – probably the best, as it was a first-hand account. His brilliant cricket mind wasn’t just confined to on-field tactics. He loved cricket and greatly respected everyone involved. When he saw opportunities to enrich the game, he grabbed them.

Now, as a full-time journalist, his motives hadn’t changed at all. Quietly incensed by the throwing accusations that ended Ian Meckiff’s career (rumours that he meekly submitted by not questioning umpire Colin Egar, who no-balled the Aussie quick, were untrue), he took a camera to the Caribbean in 1965 to film the action of the West Indian quick Charlie Griffith.

In 1976, convinced that punishing sportspeople was not the way to end apartheid in South Africa, he gladly managed a “rebel” team. Whether they agree or disagree, even the most one-dimensional thinker could never dream of pasting the “racist” label on Richie. It would be like calling Billy Graham an atheist. While over there, he took advantage of his proximity to insist that coloured players be selected in opposition teams.

When Kerry Packer threatened to take the game out of Establishment hands, Richie was there, and became the face of World Series Cricket, which began its two-season life in 1977-78. He became an Australian summer institution.

Richie was all about change for the better. He showed the world what rebellion and revolution can achieve done with the right heart; with love. He conducted his insurrection with dignity, calm, courage and vision, over a whole career.

Benaud wasn’t afraid of personal cost if a principle was involved. His actions were carried out in the interests of the game and its players, politics be damned. He had the mind of a mediator, a facilitator in everything he did.

As a commentator, he was inimitable (despite Birmingham’s efforts). He chose words carefully and made astute judgements, without judgementalism. Many stories have been told, most revolving around what he didn’t say. But Richie did more than let the action speak. His signature silences were true pauses which sharpened our anticipation of sometimes-sharp words.

A gem of commentary I remember came about 20 years ago. A batsman, unhappy at getting out, turned and smashed the stumps. It was a wicket, therefore an opportune time to hear from the sponsors. Richie said nothing, and the longer he said nothing, the more his displeasure filled the air. It seemed he’d allow the moment to hang there, without comment. Then he spoke, in the flattest of tones: “Take a lot of punishment, these modern bats.” Ad break. It was priceless, poetic, subtle and trenchant. That beautifully timed, perfectly aimed remark said everything about what had occurred, and so much more.

Richie was cricket’s highest advocate ... a cricketer of real influence, the finest of captains, the supreme leader, a humble man, a great man – and, of course, an innovator at every turn.

Related Articles

Luck of the Draw

Harman hails lookalike Ponting as 'handsome fella'

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)