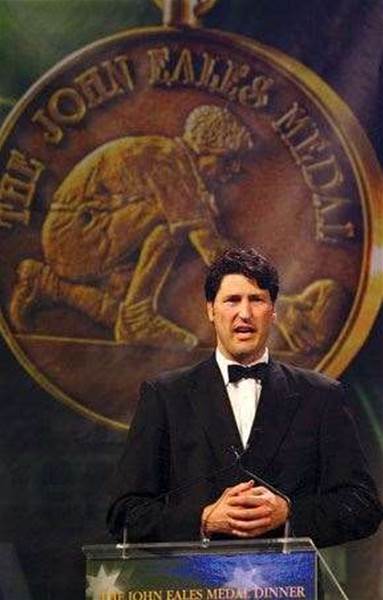

Eales’ reputation is arguably the most unblemished of any sportsperson in Australia in the last two decades.

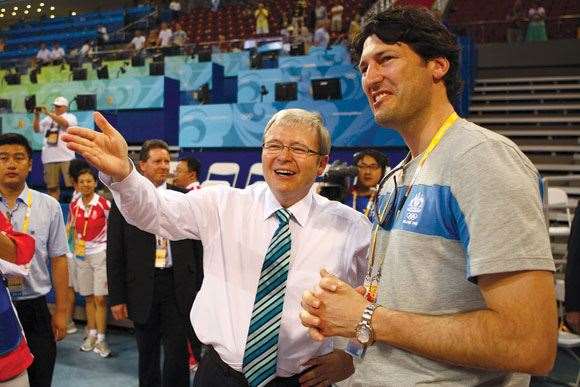

photos by Getty Images

photos by Getty ImagesDo teams have to like each other to play well?

Not really, funnily enough. I think there can be a lot of competitive tension – there can even be quite open dislike between people – as long as they’re united in a cause. So liking is not important, but uniting is. I think any team’s like that, whether it’s business or sport. There are some more natural bonds that do develop when you do like each other; if I think of the great teams I was a part of, most people at least liked each other. Some teams have a lot more good feeling, but I don’t think it’s a prerequisite.

That’d be a message you could take into the business world, too, wouldn’t it?

Oh yeah. There’s an awful amount of selfishness in business, as there is in sport. People do think from their own perspectives first, but what you do need to do is fight to make sure the selfishness that we all have – ambition, call it what you will, it can have many different titles – doesn’t overtake the selflessness you need to be a part of a team.

Sport has been used for a while now to educate the business world, but now it seems to be coming back the other way a lot, with corporate thinking governing the organisation of footy teams. Is that always a positive thing?

Rod Macqueen was very big about bringing business principles into the (Wallaby) team, and there’s no doubt that what took us ahead were some of the rigours that he introduced. But they’re just different terms for some of these things. There are similar foundations in sport and business or in life. And the terms you use for them go through fashions ...

What is it about the term “composure” and the sport of rugby union? It’s a concept rather heavily worked over in the lexicon of the game ... As if the only reason a team wins is because they have composure, or lose if they don’t have it ... What does it actually mean? Is it just an absence of panic at pressure points in a game?

Composure is the result of getting a lot of things right – you can’t just declare that we’re going to be a composed team. I think it’s clarity in the moment, but you don’t get that clarity unless you’ve gone through the routine. A lot of people will say, “Oh, he’s a great instinctive player and creates a lot of things.” Now, a sport like rugby lends itself to individual brilliance. But unless there’s structures there to give a chance for that individual brilliance to shine, it won’t happen, and part of being able to capitalise on those big moments is being composed. It’s about having a routine you can go back to.

Like a mental routine? ... Like what went through your head before a kick?

Ben Perkins was my kicking coach. I created my routine myself, but he would reinforce the importance of being yourself in those moments,

and so for me it was about having a routine in which I could be myself. So you could actually retreat to the sanctuary of that routine when you had the pressure moments. And for me it was just place the ball, make the decision of where you’re going to aim for, three steps back, three steps across, head down, slow, and follow through to the posts.

And you’d say those things in your head?

I’d say head down, and I would actually pick a specific stitch on the ball to look at. Slow – I’d just remind myself to go slowly through the kick instead of rushing it. Follow through to the posts ... And then I’d say to myself: “The only thing that matters is the ball.” And so that routine would cut out all the pressure of the situation. I mean, you still feel excited and tense, but it would just bring you back to what’s important. So that to me is composure. And so you can train it. You build your routines – you can train it through your preparation, not being surprised by a situation. Even though you come across new things in sport, the more you can be excellent at the routines that repeat themselves, the more you’re going to react better to the things that are different.

Your career straddled the progression from amateur to fully professional. Did football become less fun once it became moneyball?

Not at all – in some ways it became more fun. Some people look back lovingly at the amateur era, but I don’t. I say they were equally as enjoyable. But the great thing about the professional era was that it gave you the opportunity to devote yourself to something you love doing. Like, I came through the time where you would go to the gym at 6am in the morning, go straight from there to the office, leave the office at 5.30pm so you could be at Ballymore at 6pm, and you’d leave Ballymore at 8.30pm or so at night, go home and get a feed (lucky I was living at home), then do it all again the next day, and that was really hard. And I wasn’t supporting anyone through that time. The tours were great, but it definitely became easier when it became professional. A lot of people will say that the personalities have disappeared from the game – the personalities are still in the game, they just express themselves differently ...

How did the body hold up after your career? Can you get out of bed without pain these days?

I probably have more aches and pains than if I didn’t play rugby, but then I might be diabetic or something like that. The shoulder I am aware of, because I had two full reconstructions – I can’t do heavy weights above my shoulders. But I don’t seek to really do heavy weights above the shoulder. But it doesn’t stop me doing anything, really ...

But you could’ve played longer, couldn’t you?

Physically I could’ve, yeah. I’d just had enough, really. I still enjoyed the playing, but I just wanted to do other things.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Wallabies looking for inspired performance in RWC quarter-finals