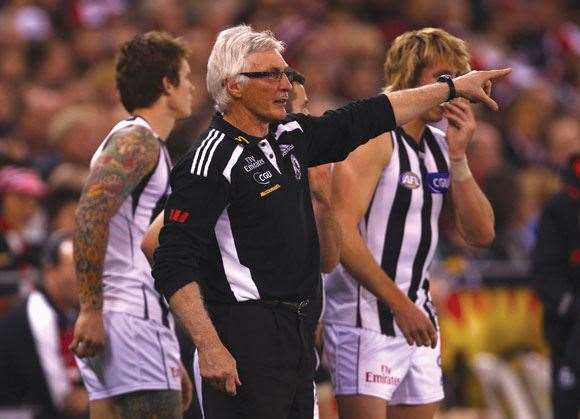

Leonine Mick Malthouse, who, in costume, made the corporate buttoned and badged tacky black-and-white tracky almost debonair.

photos by Getty Images

photos by Getty ImagesTeams you coached played different brands of footy. What were the common things each had – the non-negotiables? Solid defence. To use a soccerism, good strikers; people who can score. But that’s peripheral to discipline and unity. Eighteen blokes with one goal and one method. Loyalty. Then you’ve got hope. Then you put in strategies, game structures. They come about because of changes in the state of the game. You’ve never won successive premierships, but you did get right back up there.

What are the main challenges a premiership-winning side faces? Expectation. It’s been 75 years since Collingwood won a premiership and actually played off the next year. We did it in 2010-11. That shows how hard it is at Collingwood. Expectation is an entity in itself. Hunger. You can measure how fast you can run, how high you can jump, but you can’t measure hunger. You’ve got to rotate players till you find the hungriest, and inspire the rest. Clearly an individual’s got more chance to be regularly successful, because a team has so many components. Ten might stay hungry, ten are hungry in their first year, but have this fraction of “it doesn’t matter now, I’ve won”, and they contaminate the others. Blokes like Federer are driven to be number one, then driven to be number one again, and again. But what if Federer was playing doubles? The more numbers you add, the more parts to the machine, the more complex it gets.

When you made that handover agreement with Eddie and Bucks, you were undergoing some bad times. All good now? Your mother doesn’t get resurrected. Your daughter’s baby doesn’t come back.

How did you feel about Ben Cousins? Very sad. When I coached him I enjoyed the way he played. He’s a terrific bloke. It looked as though he was over certain areas of drugs, but you could see he might go backwards at first. To see such a young, energetic, enthusiastic person affected like that – I feel terrible for Ben and his family. I know his family. Chris Mainwaring’s passed. You reflect a lot about your time in football and who’s got up and who’s suffered.

What’s the best coaching achievement you’ve seen in football? Who’s the best coach, or who coached the best side? That’s what you’ve got to ask.

Paul Roos? That doesn’t stand out more than Worsfold the following year. Or Matthews’ three-peat. Or Chris Scott’s 2011. It’s hard enough to win them. It would take too much away from anyone who’s won one to say.

In your pantheon of inspiring or remarkable human beings, are there any footballers or football people? No. The AFL is no more than a pimple on a rhinoceros’ backside. Mandela is significant. What Thatcher did in Great Britain, Ghandi – world significance. Gorbachev. What Ferguson does for soccer, what individuals do at AFL level – it’s sport. There are far bigger matters. When did you decide you weren’t up for the director of coaching role at Collingwood? It’s not that I wasn’t up for it. It wasn’t going to fit. That was very evident.

When did you realise that Collingwood couldn’t win the 2011 Premiership? Twelve minutes to go. But I knew it was going to be tough, leading into the finals. Momentum is one of the greatest things on Earth. We’d lost momentum, and to beat West Coast in that first final was unbelievably satisfying. With players injured and suspended, we went in against a side running hot. To beat Hawthorn in the preliminary final was outstanding. We had no right to win.

Is that why you were so visibly affected that day? You get caught up. It was 75 years since the club had played off, and I could understand why, and I thought all our plans ... I knew we had to hold Hawthorn and not let them get their game together, because we were underdone. To see those plans start to take effect, hold on, just make sure they don’t get away, and we forced that issue about six or seven minutes before three-quarter time. I noticed a shift. Their frustration started to show. Once that happened we were a real chance. Then to get the lead and lose the lead and get it back ... if you’re not emotional in sport, you’re not emotional about anything. Hawthorn knew they hit us with their biggest shots and couldn’t put us down.

One thing you share with Sheeds is you see people in terms of time and life and where they are on that cycle. Where did you get that? I try to understand where people are, so I can give them resources to be better. People have a right to feel special. When you give an opportunity to someone, they want to feel like a contributor. So when their time comes, they think they’re needed. When you think you’re needed, you have ownership. When you have ownership, you surrender last, and you’ll go to the death. James Clements was a bit unsure of himself, but with surety he was one of the outstanding players I’ve coached. Anthony Rocca was sadly devalued by many. We needed him out there.

You’ve said you don’t try to be anything but what you are. What are you, Mick? You’ve got flaws, acknowledge them. Address it. I tried to give people a chance. I believe in doing it together. If you think you’re the most important person, you rob others of their importance. I’d like to think these things transfer to other areas of life.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Socceroo star's message to kids: Don't be an AFL player