While men’s tennis enthralls with its quartet of superstars routinely battling it out for supremacy, the women’s game has got problems. BIG problems. LOUD problems ...

While men’s tennis enthralls with its quartet of superstars routinely battling it out for supremacy, the women’s game has got problems. BIG problems. LOUD problems ...

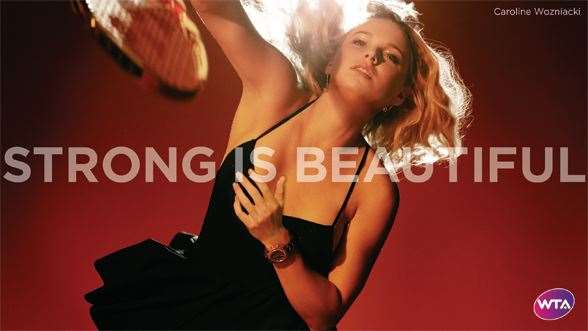

“Strong Is Beautiful”. Only, we don’t see much “strong”. We don’t even see a racquet. But we do see soft-porn lighting, loose blonde hair, shiny eye-shadow, glossy lips and a spaghetti-strap black number that’s clearly not tennis wear.

“Strong Is Beautiful”. Only, we don’t see much “strong”. We don’t even see a racquet. But we do see soft-porn lighting, loose blonde hair, shiny eye-shadow, glossy lips and a spaghetti-strap black number that’s clearly not tennis wear.The double-headed cover of tennis’ 2012 Media Guide said it all for the state of men’s and women’s tennis. This is the shop window for the respective tours to serve up their marketing aces. The men have Novak Djokovic as a modern-day gladiator, chest-out and in full cry, dominating a multi-tiered colosseum under a glowering, gods-are-angry sky. Sparks fly off his bristling frame; his racquet a smouldering sword of Excalibur ... The flip-side women’s cover has a barely recognisable Caroline Wozniacki behind the ghosted words of the WTA’s marketing campaign: “Strong Is Beautiful”. Only, we don’t see much “strong”. We don’t even see a racquet. But we do see soft-porn lighting, loose blonde hair, shiny eye-shadow, glossy lips and a spaghetti-strap black number that’s clearly not tennis wear. A caption is needed to identify Wozniacki and explain her cover-girl status: “2011 Year-End No.1 Singles Player.” Djokovic needs no name tag. Nor a tennis-boffin explanation of his standing in the game. He’s No.1. The Man.

That’s it in a quick serve. The difference between men’s and women’s tennis. Illuminating, too, is how the last year unfolded for the respective No.1s. Djokovic is again on top, the winner of six titles in 2012 and the only man to contest three major finals (winning the Australian Open in a record-setting epic that delivered truth-in-advertising on that Media Guide cover). Wozniacki, meanwhile, was dethroned by the end of January, made one major quarter-final and fell from the top ten.

While men’s tennis basks in a golden era, women’s tennis makes the Eurozone look like a model of stability. The men’s tour boasts the most dominant foursome in the history of the game, the Big Four of Djokovic, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Andy Murray, with 34 Grand Slams between them. Since 2008, only one other man has cracked the Grand Slam club: Juan Martin Del Potro, and he had to beat both Nadal and Federer to do it. In the same period, 20 women’s majors have been divvied up by 11 players.

The tight triumvirate of Federer, Nadal and Djokovic has held the No.1 ranking since February 2004. Over the same time span, the women’s No.1 ranking has changed hands 29 times between 11 players.

In 2012, new No.1 Victoria Azarenka, mercifully free of the Grand Slam gorilla that beleaguered Wozniacki, raised hopes of restoring order to the women’s ranks with a Djokovic-like 26-0 start to the season. But the ball-crushin’ Belarusian went winless from mid-March to October and 0-5 in high-noon showdowns with Serena Williams, who launched her most audacious comeback yet to swoop on Wimbledon, the Olympics, the US Open and the year-end Championship. And so the dissonance continues in women’s tennis. Azarenka held on to top spot, Williams was Player of the Year. For the fourth year in the last five, the No.1 ranking

and the No.1 record belonged to two different women.

How did women’s tennis get in such a spin? Here are ten ways the silverware has been tarnished ...

Slamless No.1s

Nothing has damaged the brand more than Slamless No.1s. Once upon a time, you had to win a Grand Slam title ‒ or multiple Slams ‒ to get to No.1. These days, the road to the top ranking can bypass the majors. It’s a credibility crisis the men don’t have. Nobody questions whether Novak Djokovic deserves top-dog status. The men have had one majorless No.1 ‒ Marcelo Rios in 1998. The women have had three in the last five years ‒ Jelena Jankovic, Dinara Safina and Wozniacki.

Most problematic was the curious case of Caroline Wozniacki, who not only failed to win a Grand Slam, but didn’t even reach a final during her 15-month reign. The bouncy Dane barely set foot in Australia for her first major as world No.1 in January, 2011 when the broken-record line of questioning began: “Do you deserve your No.1 ranking?” Yes, it was tiresome. It was also valid. Even former No.1 Chris Evert, calling herself “Chris from Florida”, phoned in to ESPN to pose the question. The besieged 20-year-old, looking to deflect the negative focus and inject her Little Miss Sunshine persona, lobbed a spurious kangaroo-attack story that required a separate press conference and 41 questions to put the kanga in the clear, so to speak.

Wozniacki’s woes had less to do with a rogue kangaroo than a “cat’s away, mice will play” scenario. She made the most of Serena Williams’ year-long absence from mid-2010 and Kim Clijsters’ cameo 30-match season in 2011. As world number-one, Wozniacki scarcely crossed paths with top-five opponents, winning two of six matches.

No less anomalous was the reign of the hapless Safina, thrashed 6-0 6-3 by Serena in the 2009 Australian Open final and promoted to top spot soon after. Even a train-wreck 6-1 6-0 semi against Venus Williams at Wimbledon didn’t displace her. Serena won the Big W, but Safina stayed No.1. “I think if you hold three Grand Slam titles, maybe you should be No.1 ... but not on the WTA Tour,” Serena seethed.

Safina recently came out in defence of Victoria Azarenka as a legit No.1, in a thinly veiled reference to her own experience. “The No.1 is not the player who selectively plays major tournaments, even winning them, but the one who is stable over the full season,” said the Russian. “Let the younger Williams play a full season, and then we’ll see who will be the No.1.” Safina copped a raw deal in many ways ‒ not least the likely end of her career at age 25 ‒ but self-interest is trumping logic here. So Serena would be ranked lower if she played more? She rolls through Wimbledon, the Olympics and the US Open ‒ but let’s see her win Tokyo, Toronto and Tashkent!

In the men’s game, the ascension of a new No.1 has logically followed a seismic win on the court. So Roger Federer first rose to No.1 as the Wimbledon, year-end Masters and Australian Open champion. Rafael Nadal dethroned Federer in the classic Wimbledon final of 2008. Djokovic displaced Nadal after beating him in the 2011 Wimbledon final. Federer took back No.1 after defeating Djokovic and going on to win Wimbledon last July. Increasingly on the women’s tour, the rankings seem the product of a mysterious mathematical formula rather than “game, set and match” on centre court.

The players don’t design the rankings system? Well, yes. And no. The ranking system is the product of negotiation with the players. On both tours, the rankings formulae have been tweaked over the years ‒ mostly to induce the stars to play more.

A concession the top players won was the scrapping of bonus points, a sliding scale of bounty points that weighted quality wins according to calibre of opponent. So a player who reached a final by beating Serena earned more points than a fellow finalist who beat a qualifier. The top players felt this bounty on their heads advantaged lower-ranked players, who could swing from the heels and advance faster up the rankings at their expense. The upshot is that wins are counted all the same. The ranking system today is a far blunter instrument for slicing and dicing the numbers. It essentially measures quantity over quality. Ironically, a system that was supposed to benefit top players has robbed the No.1 gong of its legitimacy and lustre. Even the reigning No.1 ranks majors success above the top ranking. “It’s just a number,” Azarenka said at the US Open. “It’s a great achievement, but it’s nothing like lifting a [Grand Slam] trophy.”

If bonus points were still in play, the No.1 player of 2011 would likely have been Petra Kvitova, the Wimbledon, WTA Championships and Fed Cup winner ‒ and the WTA’s own (media-voted) Player of the Year. In ten of the past 15 years, the Player of the Year has not been the No.1-ranked player.

Revolving-door No.1s

No.1-ranked women are becoming like buses on Broadway: there’ll be another one in a minute. Blame it on Justine Henin. Since the last dominant No.1 abdicated in May 2008, the keys to the penthouse have gone back and forth 17 times among eight women: Maria Sharapova, Ana Ivanovic, Jelena Jankovic, Serena Williams, Dinara Safina, Caroline Wozniacki, Kim Clijsters and incumbent Victoria Azarenka. In 2008 alone, five women held the top spot.

Playing hot-potato with the No.1 ranking, for whatever reason, is like minority government: it’s tolerated, but not indefinitely. Top players have to prove why they’re up there, or they lose credibility and fans lose interest.

Where are the rivalries?

The most damning stat for women’s tennis emerged from the final between Victoria Azarenka and Maria Sharapova at Indian Wells, California, last March. This was the first final showdown between the No.1 and No.2 women in four years. Between 2005 and 2011, the top two women faced off a grand total of three times. In seven years! A far cry from the Chrissie-Martina glory days. And inconceivable on the men’s tour.

Top rivalries are the lifeblood of the sport. Yet for whatever reason, the top women don’t clash often enough. Intriguing match-ups abound, but the output is anaemic, certainly compared with the meaty match-ups on the men’s tour.

The last Grand Slam final between the top two women? Rewind to the 2004 Australian Open between Justine Henin and Kim Clijsters. Since then, the top two men have faced off in 13 Grand Slam finals ‒ seven of them Federer-Nadal blockbusters.

The “Real” No.1s

The other side of the net from Slamless No.1s are the “real” No.1s who couldn’t extend their dominance beyond the majors. When Justine Henin handed over to Maria Sharapova, the Russian was already struggling with an injured shoulder that would require surgery. Kim Clijsters wouldn’t compromise her family-friendly schedule at the end of 2010 for the trifle of the No.1 ranking. But it’s Serena Williams who personifies the disconnect between No.1 ranking and de facto No.1. The greatest player of her generation is yet to rule for an entire year as No.1.

In 2012, the powerhouse Californian pulled off her best comeback yet ‒ from multiple foot surgeries, a haematoma and life-threatening blood clots in the lungs, not to mention a drop to almost 200 in the rankings ‒ to once again stamp herself the true No.1. The WTA’s Player of the Year. The greatest of all-time, according to current No.1 Victoria Azarenka. But No.3 on the computer.

For Williams is about winning majors rather than chasing ranking points. “Gosh, I want to pick up [an extra] tournament because I did so awful here,” Serena lamented after her shock loss to Ekaterina Makarova at Melbourne Park last January. “But there’s no tournaments.” Acapulco was coming up, and not far from her LA home. “Yeah? I’m not that desperate,” quipped Her Sereneness.

Who can argue with the winner of 15 Grand Slams?

Not-so-Grand Slammers

Shooting stars have blazed across the Grand Slam firmament, only to fizzle just as quickly. Glamazon Ana Ivanovic bagged the 2008 French Open and No.1 ranking and never got within cooee of both again. Svetlana Kuznetsova has fallen off the radar since winning Roland Garros in 2009. Tattooed trailblazer Li Na may have touched off a tennis boom in China by sweeping the 2011 French Open, but needed 14 months to win another event and hasn’t been back to the quarters of a major. Wimbledon 2011 winner Petra Kvitova likewise went a year before her next tournament win. And Sam Stosur is titleless since her shock straight-sets defeat of Serena Williams in the US Open final.

Glamour overkill

We’ve come a long way since Justine Henin posed with her 2003 French Open trophy in faded jeans and black T-shirt. Probably too far ... into red-carpet “look what they did to my face, ma!” territory. Yes, women’s tennis is blessed with a bevy of stunners who wouldn’t be out of place on a catwalk. Yes, we like to see the stars (not just WAGs) frock up occasionally. But the glamming up of the women’s game is relentless. Not every player relishes being poured into a designer gown, shoe-horned into Jimmy Choos and paraded before the cameras.

The “Strong Is Beautiful” campaign is artfully shot, but there’s nary an intimidating muscle or a bead of sweat in sight, which calls into question whether the WTA believes its own marketing. It’s hard-selling beauty above strength, glamour over game. (See also Media Guide rant above.)

God-awful grunting

Never mind that John Newcombe, for one, long ago declared grunting “legalised cheating”. The women’s tour finally got the message via fan polling in 2012 that told us the (ear) bleedingly obvious: grunting is a major turn-off for many fans.

Far from being as natural as breathing (as the shriekers claim), it’s a blight on the game that’s been tolerated for far too long. As Maria “Shriekapova” archly put it, “No one important enough has told me to change.” Moves are finally afoot to curb the farmyard stereophonics, though the changes will be imposed on aspiring juniors, not the scream queens. So keep those ear-plugs handy.

Ridiculous gesticulating

Victoria Azarenka and co pull more fist-pumps in one match than Roger Federer has in his whole career. Ana Ivanovic starts with the “Ajde!” in the warm-up. Recently I watched an Evert-Navratilova final via the miracle of YouTube. They hit a bazillion winners. Zero fist-pumps. Let’s dial down the emotional volume, ladies. It’s the tennis equivalent of Spinal Tap turning it up to 11.

5-1 down in the third

Feigning and exaggerating injury, or retiring at 5-1 down in the third set, are this decade’s version of the strategic bathroom break. You always want to give an athlete the benefit of the doubt, but some scorelines make you wonder whether it’s about avoiding further injury or robbing an opponent of the winning moment.

At Doha last February, Victoria Azarenka and world No.3 Agnieszka Radwanska got into a spat after the Pole accused her friend of playing up a rolled ankle. “I was angry because I don’t think this is the great image for the women’s tennis,” charged Radwanska, who lost both the match and “a lot of respect” for the new No.1. Azarenka also copped a sly serve from Maria Sharapova after the Russian beat her in the final at Stuttgart. This match also featured an Azarenka medical time-out, with Sharapova sarcastically telling the crowd it was a pity that “Vika was extremely injured today”.

Yet another contentious time-out by Azarenka came at Beijing in 2009 when Sharapova asked the umpire: “Is her last name Jankovic?” A not-so-subtle shot at former No.1 Jelena, a self-confessed drama llama who reflexively called for the trainer.

Never-ending end

You would think the season-ending finale for the top eight players, the WTA Championships in Istanbul, is the way to end the year with a bang. You would be wrong. The year-end Championships is followed by the Tournament of Champions ‒ in the tennis backwater of Sofia, Bulgaria ‒ for players (the Champions of the title) who didn’t qualify for the Championships. The WTA calendar blocked out eight-ten weeks of off-season, but belatedly added lower-level events in Taipei and India. During the off-season. A messy and confusing end to the year.

For all the women’s issues, there’s also hypocrisy at play. Not so long ago, women’s tennis was derided for being predictable and lacking in depth – “Steffi and the Seven Dwarfs” cracked Martina Navratilova – but the men are lauded for their predictability; the Big Four takes its semi-final slots as if set in cement, and that’s a good thing ...

Women players were once dismissed as powder-puffs and moonballers who couldn’t muscle the ball away. Now that the game is grunt-physical enough to make an SAS commando dry-retch, critics lament the loss of variety and touch.

After years of headline rivalries, the women’s game is in a turbulent, transitional phase, while the men bask in an era of excellence. The Dunlop Volley is on the other foot. At the tail-end of the Pete Sampras-Andre Agassi era, it was the men who were in flux, with No.1s including Thomas Muster, Marcelo Rios, Carlos Moya, Marat Safin, Juan Carlos Ferrero and our own Pat Rafter for one week. From 2000-03, the 16 Grand Slam titles were divvied up by 11 men. No man would ever dominate the game again, it was believed. Parity was the new normal. A decade on, that changed paradigm has become reality not in the men’s game, but the women’s.

Yet, if women’s tennis is not basking in a belle epoque to compare with the men, tennis is still clearly the No.1 women’s sport ‒ tougher, more telegenic and more global than ever. The women of tennis will take up their positions on the baseline and no doubt play out another saga at this year’s Australian Open ‒ just not the plotlines we were expecting.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open