Could Mitch become the best left-arm Aussie quick we’ve ever seen?

His World Cup exploits announced the arrival of our newest pace demon. Since then he’s only gotten better. And faster. They’re really talking him up now ... Could Mitchell Starc become the best left-arm Aussie quick we’ve ever seen?

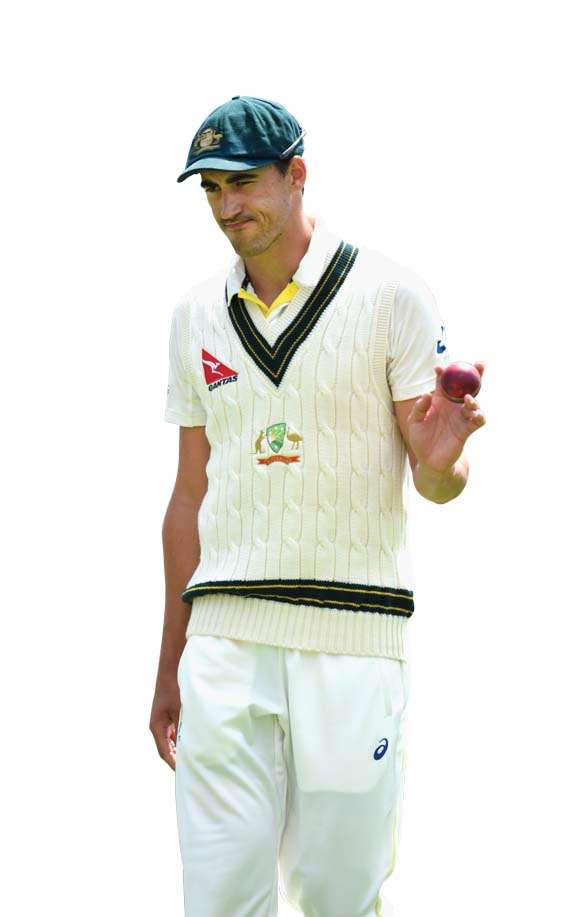

Fast bowlers need good nostrils. Wide, snorting nostrils, incensed and bad. Nostrils like the wings of a frill-necked lizard. Crazy nostrils. Crazy eyes, too, are good (and bad). Eyes that make a batsman think the bowler wants to hurt him. Dennis Lillee had them. Curtly Ambrose and Malcolm Marshall had them. Colin Croft was born with them. Dale Steyn’s biography could be called “Scary Eyes, Snorting Nostrils – The Dale Steyn Story.” Jeff Thomson had the eyes of a bull shark: dead on approach, straining blood in delivery stride, then black and dead again up close. Thommo scared more batters than Whispering Death.

We’re looking into Mitchell Starc’s eyes in a restaurant just off Dee Why Beach on Sydney’s northern beaches. It’s a few days after the mad fun of the pink ball Test in Adelaide (in which he only bowled nine overs) and Starc is wearing a moon boot to rest the foot injury that’s ended his Test and summer.

Yet he’s looking pretty relaxed. There’s a bottle of Mexican pale ale in his mitt and cool, reflective shades on his head. Black eyebrows sit low above long features. There’s an aquiline nose, delicate nostrils, good long chin. It’s a sort of aristocratic face, like the nephew of Camilla Parker-Bowles, the nice one from Buckinghamshire, plays a bit of polo, dates his second cousin, doesn’t appear to have a job.

Starc is not dating his cousin (but rather is engaged to Alyssa Healy, wicket-keeper for Australia’s Southern Stars). And he’s far from a jobless aristocrat, being born and bred in Lidcombe and Baulkham Hills in Sydney’s greater west, the great Aussie ’burbs famous for Canterbury Bulldogs and Parramatta Eels, mega-pubs and super-churches.

During our hour-long chat Starc’s eyes are alternately studious (when considering the question), twinkling (when talking about cricket), or wary (when talking about his injuries). It’s clear that he loves the game, but doesn’t like talking about his body.

Talk to Starc’s mates and they’ll tell you he’s the classic “white line fever” man. In the sheds he’s the nice, even, shy kid at school. Out of the dressing shed and down the race and through the white picket fence and he’s a bad-ass. The eyes morph into bad ones. There’s focus and laser-beam intent. He’s still relatively hard to cop as the bully boy, the tough snorting pack animal – there’s enough of the kid left in his skin. But as Tony Montana says, “The eyes, Chico. They never lie.” Starc wants to hit the seam or whatever’s in the way.

“I’m not really that aggressive-natured, James Pattinson-style bowler,” offers Starc about the person he becomes on the field.

“I guess the way I’ve gone about my cricket, I try to let actions do the talking. I just try to take wickets.”

A fast bowler’s “aggression” – and the pantomime nature of blather and skite, and all that stuff about nostrils and eyes and great jutting chins – will “spill over” occasionally. It has before and it will again. Nature of the beast. Lillee toed Javed Miandad in the backside. Curtly Ambrose wasn’t far from bopping Steve Waugh on the head, like Obelix. Craig McDermott, currently Australia’s fast bowling coach, just about pioneered the act of hurling the ball back at the stumps on collecting it on follow-through.

That McDermott only ever hit the stumps once, against the West Indies when he was 19, hasn’t stopped bowlers doing it ever since. McGrath did it. Warne did it. It’s never run anybody out but it’s a “tough”, aggressive play if you’re a fire-breather and leather-flinger. It says to the batter, You get back in there, Puppy, lest I ping this hard rock quite near you. They’re not out there to be nice.

In summer’s first Test in Brisbane, Starc threw the hard red rock close enough to Kiwi No.8 Mark Craig to be fined $7725, half his match fee. Starc said after the match and during our lunch that he didn’t want to hurt the bloke, it was just a dud throw. Yet Starc’s captain, Steve Smith, fresh and slightly insecure, looking to make a mark, told him to stop it. It cost four overthrows. And the run-out wasn’t on. And Australia’s cricketers, again, copped that “Ugly Australian” and “bully-boy” thing because Starc was being too “aggressive” to a Nice New Zealander. You’ll recall it was Starc who threw the ball that caused Ben Stokes to flinch and pop out his hand lest it hit him or the stumps, we may never know.

So how does Starc play the traditional Australian brand of “aggressive” cricket, without upsetting officialdom? He reckons it’s always on his mind. “But at the same time we’re trying to win games for Australia. That’s first and foremost for us. Obviously we’re always in the limelight and we are conscious of what people might think. But we are just trying to win the game for our country.

“So we’ll continue to play aggressive cricket. That’s how we play our best cricket. But it’s important we don’t over step that line. We have in the past and I’m sure we will in the future. And we’ll hear about it.”

But where is this line? I ask. Don’t you only know if you’ve over-stepped it when someone tells you that you have?

“A lot of the time the officials decide where the line is,” admits Starc. “There’s been times in the past when a bit of friendly banter’s been perceived as something different. Other times things have been let go. But as the Australian team we have to know how the public views things. And how we view things ourselves as well.”

Maybe the fine is fair enough. Maybe someone has to think of the children. Maybe the Nice New Zealanders should get more respect. Or maybe you could argue it was a mark of respect for Craig that Starc wanted to work over whoever was in the way, be it inoffensive all-rounder from Auckland or a cock-sure swinging dick like Kevin Pietersen.

Either way it’s clear that Starc, with the retirement of Mitchell Johnson and Ryan Harris, has assumed, at the prime fast-bowling age of 25, the title of chief wild-eyed, flare-nostrilled spear-chucker and crazy man.

Starc’s time is now.

RARE AIR

In a home-made backyard cricket net on his property in Wandering on Western Australia’s wheat belt, former Test opener Geoff Marsh (father of Shaun and Mitchell) would ask his wife Michelle to feed cricket balls into a bowling machine. And towards the end of the hour-long session, for something to do, he’d ask Michelle to crank the machine up to 160km/h, the fabled 100 miles per hour. Crazy speed. Thommo speed. Marsh made sure never to rile Michelle before a net session ...

It’s advice you’d give anyone facing bowling that quick. Those who’ve been timed at such supersonic speeds are a select group: Jeff Thomson, Shoaib Akhtar, Brett Lee, Shaun Tait and, of course, Mitchell Starc, who flung down the fastest ball ever recorded in Test cricket. Consider those not among this rare air: Dennis Lillee, Dale Steyn. Andy Roberts clocked 159.5 in 1975 and Michael “Whispering Death” Holding did not (though he bowled as quick as Thommo on occasion, according to plenty of old lags). Others who never clocked the ton include Malcolm Marshall, Bob Willis, John Snow, Mike Proctor, Stuart Broad, Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram and Allan Donald.

Starc’s fireball came on a WACA pitch flatter than the Canning Highway. Ross Taylor, on his way to 290, defended it quite easily. Yet after the day’s play he and Brendon McCullum acknowledged that Starc’s spell was blindingly quick. It broke McCullum’s bat. And no one likes it blinding quick.

“That whole spell felt pretty good,” says Starc. “Breeze over the shoulder. Had it swinging a little bit. The spell was definitely faster than anything I’d done in the match. In that situation, friendly batter’s wicket, you’re just trying to create something. And I was in a good space and the ball came out faster and faster. Had a laugh about it after the game with Ross and Brendon. They said it was pretty quick as well.”

A few years ago Starc had a session with the great Wasim Akram, who told him to relax his wrist to make the ball swing. Starc keeps it in mind for his entire body. “Rhythm is the biggest thing. There’s times when you’re trying too hard; it doesn’t come out right. There’s times

when it seems easy. It mightn’t even feel fast, but everything’s working nicely; your body is upright, you load up at the crease and everything comes out perfect. That’s when it comes out quickest. Those times don’t come along every day.”

MILD CHILD

The Hussey brothers, Michael and David, would play “murderous” matches on the concrete slab of their beachside home in northern Perth. There were tears and shouting and fighting. David would refuse to bowl ... and lock himself in the car. There were similar scenes of competitive tension in the Chappells’ backyard, the Waughs’, the Warnes’.

The Starcs’? Not so much. Mitchell’s brother, Brandon, an Australian high jump medal hope for the Rio Olympics, is four years younger. The pair were competitive but in the main good mates. And they just played. In the cul-de-sac, in a car park of a warehouse nearby. Heap of games, heap of mates. Roofs full of tennis balls. The odd broken window. And they did all sports.

But cricket had Mitchell. He presented at Green Shield (U/16s) trials with Sydney clubs UTS-Balmain, Parramatta and Western Suburbs as an all-rounder who kept wicket. But it was only the latter who saw potential. It was there that Wests head coach Neil D’Costa, mentor of Michael Clarke and Phillip Hughes, told Starc that he was a bowler.

“I was head coach of the club, the seniors,” says D’Costa. “But I’d always go down and see what was happening in Green Shield. And I saw him throw the ball from the boundary. And he threw it hard and long and flat, and I thought he must be a fast bowler. Usually the guys that throw hard bowl fast. And he was tall.

“At training I said, ‘Mate, you’re a bowler.’ And he said, ‘I don’t like bowling.’ And he’s arguing with me. And I said, ‘Mate, for fuck’s sake, I’m the head coach here, so bowl the ball.’ Begrudgingly he bowled.

“So I invited him to the high-performance camp and I remember his Dad [Paul] said, ‘Why is he here as a bowler?’ And I said, ‘Bear with me.’ And I taught Mitchell his action over one step, two steps. And we went from there.”

Starc remembers “arriving at Wests where Neil said, ‘You’re not a wicket-keeper, here’s a ball.’ At the indoor nets he gave me a bucket of balls and said, ‘Go and bowl off one step.’ That’s what I did for two hours. The next week it was two steps, then three steps. And I got better. And I think that’s why I’ve stayed pretty natural and not too mechanical.”

Soon enough he played second grade, then first grade. In a match against St George at Hurstville Oval he took seven wickets, bowling poorly. “It was some of the worst bowling I’ve ever seen,” says D’Costa. “Full tosses, wides. We presented him the ball and I said, ‘Remember this, you’ll never get seven wickets with that again!’ But what it told me was that good players in first grade were worried about his good balls. It was fear of the good one. He was playing for New South Wales not long after that.” And for Australia not long after that ...

By October 2010, aged 20, Starc was informed he’d be on the plane to India. He’d been chosen in the one-day squad but was travelling with the Test guys. Learning from the training regimen of senior Test men was invaluable. Discovering they were normal people was, too.

“It was my first time in India and it was all new. It was a huge eye-opener culturally,” says Starc. “I was in a hotel lobby early on and we’re waiting for the bus to training. And I’m kneeling over my kit bag to sort something and Ricky Ponting came over and just pushed me over. [Laughs] And made a big joke of it.

“I’d been watching this bloke on television play cricket for years, and here he is, nudging me over and laughing about it. It was funny. And it was fantastic. As a new kid coming in, whether you’d played no games or a hundred Tests, it was like a family.”

Two summers later he was playing for Australia A when the word came: he’d made the Test squad. “They named a squad of 15 or so,” recalls Starc. “It was an interesting time. New coach [Mickey Arthur], new setup. A few injuries. The night before the game I was told I was in the team.”

Who told him? Starc can’t remember if it was Arthur or selector John Inverarity.

“It’s a blur. I didn’t sleep too well.” He was able to get his mum to the game and his fiance Alyssa Healy was already there. He was delighted for fellow debutants James Pattinson and David Warner. Delighted when his cap was presented by the great man Richie Benaud. And he was further delighted with his first Test wicket – McCullum c Warner b Starc. “Never forget it,” says Starc. “It was a very special few days.” More would follow.

AKRAM

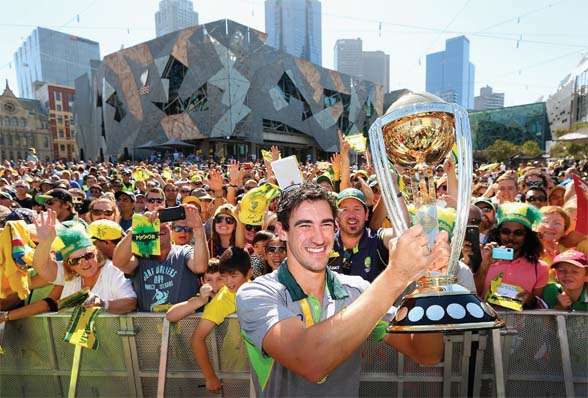

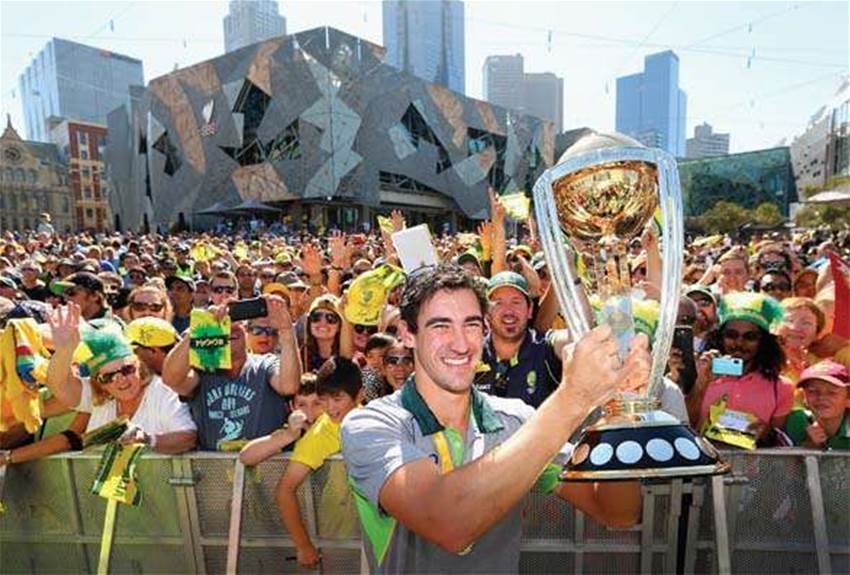

From ball one Mitchell Starc owned New Zealand in the World Cup final, owned them like Donald Trump owns things made of gold. Starc owned everybody. From over the wicket or around, wide out or close to the stumps, his yorkers were devil-balls. He was unplayable. In eight matches he took 22 wickets at 10.18. In a modern game of thick-edged bats and massive attack, his economy rate was 3.50. He took a wicket every 17 balls. He was unarguably Player of the Tournament. And he was afforded the ultimate accolade for the left-handed leather man: comparison with Wasim Akram.

Akram is the greatest left-arm quick there’s ever been. Kapil Dev reckons greatest ever, “left-arm, right-arm, all arm.” Akram would hustle to the crease, little steps, then muscle the ball, fast, with a shoulder action that was almost pneumatic. He could do you from everywhere, over or around, near in or wide out. And that late swing, both ways, conventionally, Irish ... incredible skill. As Kapil says, “He was a magician with the ball.”

They reckon another Pakistani great, Sarfraz Nawaz, first dallied with “reverse” swing (though didn’t share it with anybody, team-mates included). Terry Alderman reckons he had it going “Irish” a couple of times by mistake. But Wasim and his partner Waqar Younis, those guys made the thing sing.

Now, we’re not saying Mitchell Starc is the New Wasim Akram, because there’ll be only one Wasim Akram. He was a freak. But when Starc has that white pill hooping about at speed, and zapping into the toes at high speed, well, you can’t rattle bails better.

Australia’s best left-hander? In the pantheon of left-arm leather men there’s Alan Davidson, who took 186 wickets at 20.53. There’s Bill Johnston, who played third fiddle to Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, but not by much. Then of course there’s the frightening, if enigmatic Johnson. “Caviar” ran so hot in 2013/14 against the Poms he was DK redux. He was DK with Thommo’s fear factor. He was unbelievable. Other summers he was on the verge of giving it up. Tremendous bloke. And he also had plenty of white line fever. But he’d agree he could run a little cold, and skittish.

And there was gangling, death-from-above Bruce Reid. Never the fastest, but Reid’s height and proximity to the wicket at delivery gave him bounce and odd angles. Problem was there was nothing of Bruce Reid – his limbs were held together by gossamer-sinew.

Starc’s body has not been without rebellion. There’s ankle spurs. The stress fracture in his foot. Bummer of an injury for a quick, your foot-bone injury. He went under the knife in the second week of December. Smart money is on four months out of all cricket and loading up for the Sri Lanka Test series in July and August. Then multiple Tests against South Africa in Australia, more against Pakistan. And then we’ll see that red ball sing.

Starc says he doesn’t think the colour of the ball matters. “It’s more a tactical thing, about what’s required at the time. With the white ball you’ve got four or ten overs. I’ve played consistent cricket with the white ball. But I could be inconsistent with the red ball. But the last six months I’ve played consistent, back-to-back cricket. The last six months have been fantastic.”

Plenty agree. Indeed if you do the mathematics on Starc’s contract against his contributions in the 2015 Indian Premier League, in which he played 13 matches for the exotically-named Royal Challengers Bangalore (no Delhi Daredevils, but still), you’ll find he was paid $3848 per ball. That’s right: each delivery Starc sent down in IPL Version 8, all 258 of them, was worth $3848. Each over was worth $20,906. Every over, boom – another 20 grand. His 20 wickets were worth $44,950 a piece.

For five weeks of steamy T20 big whack action, Starc was paid $899,000, the price of a fancy Brisbane four-bedder. And all for 24 balls a game, some throwing from the boundary, and the odd bit of late whacking if he’s lucky (he scored 11 runs – you do the maths). Fun cricket, stupid money. Sick money.

For in this mixed-up world of Kolkata Knight Riders and Caribbean mercenaries and Warney and Sachin playing cricket in New York City, whatever that was, this is the coin the world’s premier white ball fast bowler can command. Starc, following his irrepressible and just about unplayable fast bowling in the World Cup, is a hotter property than Balmoral beachfront (where he has not coincidentally purchased a place, and for quite a bit more than $900k).

That he’s injured is a bummer for the cover of this magazine. There were questions about his “relevance” if his summer’s gone and the T20 World Cup is doubtful. But he still gets the cover because Mitchell Starc, at 25 years old, is the man. He’s a global superstar. The fastest and best bowler in the land.

And we just could, people, be looking at Australia’s greatest ever left-arm quick.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open