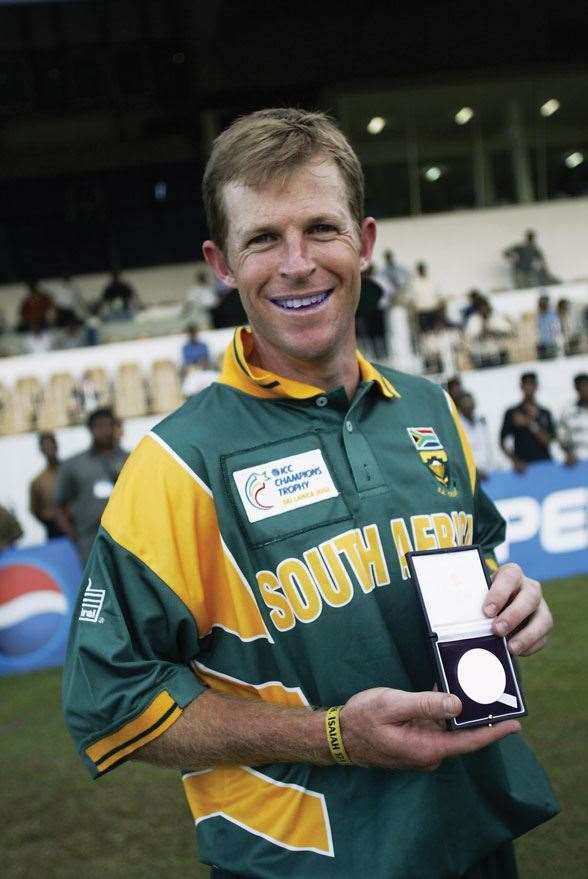

South African magician changed cricket forever.

Sometimes sportspeople become innovators by sheer force of their pioneering passion for a particular aspect of their sport. South African cricketer Jonty Rhodes was taken with the idea of studying and mastering every aspect of fielding, from anticipating a ball, through to the way he landed and everything in-between. He forced the cricket world to understand things about his art – and he came to own it like no one before or since – that it had previously never considered, single-handedly setting the standard for today’s fieldsmen.

It’s not as though fielding didn’t exist before Rhodes. In fact, the first of the renowned “specialist” fieldsmen was compatriot Colin Bland. Bland was known to have the deadliest pick-up and throw in the game’s history to that point, and was the first to draw people to matches just by virtue of his fielding.

Unlike Bland, Rhodes wasn’t a tall man, and he was nowhere near the batsman, but he provided fans with some of the most spectacular and improbable fielding moments ever witnessed. It was more than mere spectacle. He won Man-of-the-Match awards just for fielding.

Today, we see players hit stumps more often than they miss. Commentators now criticise a near-miss, whereas once it would have been a praiseworthy effort. Rhodes has a lot to do with that. He delved so deeply into the art and science of fielding a cricket ball, he seemed to only reluctantly emerge to concentrate on batting. To his credit, though, when he did emerge, he would obsess about batting as well, to the extent that he averaged 50 later in his Test career, atoning for a mediocre start (his overall average was 35).

So fixated was he on fielding well, Rhodes had every aspect covered. If it was humanly possible to get to a ball, he would. If he made ground to a bullet, he stopped it. If he stopped it, he threw in the same motion. If he threw, he hit the stumps more often than not. If he hit the stumps, a batsman was often out. If he wasn’t out, he was in two minds. If it got to hand on the full, he caught it. Rhodes guarded a vast arc of ground, normally between gully and cover, and was probably the first fieldsman to render the entire zone he patrolled out of bounds if the batsman was serious about scoring runs and wanted to increase his chances of staying in.

Rhodes was nippy, explosive, elastic, lively. He had a quick eye and safe hands. He stopped the most powerfully struck ball with one clean touch. His range of skills saw to it the batsman had no chance. His anticipation, honed as an elite hockey player, was so developed, it entered the realm of premonition, and was superior to anyone’s by tenths of a second.

Rhodes took some of the most outstanding catches, of all varieties, cricket has seen, and many would not have been taken by anyone but Rhodes. In 1993, he singlehandedly destroyed the entire West Indies team at Brabourne Stadium, Bombay, with five catches. Three in particular, which dismissed Brian Lara, Phil Simmons and Anderson Cummins, were as near-impossible as catches get.

Lara mistimed and popped one harmlessly into the air a metre. An airborne ball couldn’t be passed up by Rhodes. He sprinted in from backward point. A tumble of arms and legs, a five-metre slide. Mystified, Lara looked down at the whole catastrophe. There amongst it all, in a hand, was the ball. Simmons was victim of an inconceivable one-handed reflex take at short midwicket. Then, as if to impress us with his repertoire, with a gymnastic leap and a lightning-fast pluck as it passed him, he intercepted a powerful Cummins cut off Allan Donald.

The man was a fielding Ninja.

His ability to conjure run-out dismissals was magical. When South Africa came back into international cricket at the 1992 World Cup, only they knew what Rhodes could, and would, do. Team manager Mike Proctor warned us in a press conference. We all thought, “So what? Every team has great fieldsmen.” Proctor meant they had a fieldsman worth at least one bowler with his ability to dismiss batsmen, and one batsman as he stopped a handy innings-worth of runs.

Pakistan’s Inzamam Ul-Haq, one of the players of the tournament, found out along with the rest of us. Inzy – never a speedster – went for a run and was immediately sent back by Imran. When he took off, Rhodes was 30 metres away. By the time Inzy turned and grounded his bat, the stumps were flattened, with a horizontal, airborne Rhodes still attached to the ball. In that split-second, Rhodes had computed that the quickest and surest way to the stumps would be to run and hurl himself, ball in hand. It won South Africa the match.

In the dressing room, Proctor laughed knowingly.

Jonty Rhodes had arrived. That moment, and his subsequent exploits, inspired coaches around the world to ensure fieldsmen would commit to fielding as never before. It changed the game forever.

– Robert Drane

Related Articles

Luck of the Draw

Harman hails lookalike Ponting as 'handsome fella'