Is the FIA’s plan to introduce overhead cockpit protection on Formula 1 cars a long-overdue measure, or is it taking the quest for driver safety into absurd territory?

It seems that Formula 1 has lost its halo. Or to be more correct, next year it won't be getting the halo that it never had in the first place. That’s because enough teams voted against the controversial FIA proposal for 2017 to fit cars with the Ferrari-developed, wishbone-shaped F1 overhead cockpit driver safety enclosure – the so-called Halo.

But that’s not the end of it. According to F1 Race Director Charlie Whiting, the decision not to proceed was merely a 12-months deferment, so that ‘all options’ could be considered. When quizzed, he said that ‘some kind of cockpit defence’ will be adopted in 2018.

Whether that’s the Halo or some other concept (like the Red Bull ‘Aeroscreen’ which was shelved due to it failing the hit-by-a-wheel-at-250km/h test), will depend on further evaluation.

But if, as Whiting says, overhead protection devices in F1 are a fait accompli, hopefully something a little more considered (and perhaps a little less ungainly) will emerge over the next 12 months. The situation was probably best summed up by Red Bull team principal Christian Horner when he described the Halo as an ‘inelegant solution’: “…and I’m not so sure it is a complete solution. Rather than do half a job it’s better to take a bit more time and do it properly.”

Let’s not kid ourselves here, either: what’s being proposed is a very big change. The open cockpit of a racing car is something the sport has always known and accepted as a particular essence of openwheeler racing. It’s the time-honoured delineation between single-seaters and touring/sports cars: as the cliché goes – racing cars do not have roofs and doors.

The Halo may even influence the design evolution of F1 cars because, Whiting asserts, it will be a structural part of the car, a kind of secondary roll structure in addition to the front roll hoop. It’s not going to a thing that’s simply attached to the top of the cockpit.

The push for the Halo concept has come from recent fatalities involving drivers being struck in the head: Henry Surtees’ death in 2010 after being hit by an errant wheel in an F2 race was the catalyst for the Halo concept, but since then in Indycar racing Dan Wheldon and Justin Wilson have each perished in (broadly) similar circumstances. The hope is that the chances of these kinds of fatalities occurring can be eliminated or in the least dramatically reduced.

As for the men whom the Halo is intended to protect, opinion is divided. On social media earlier this year, when the device was first unveiled, Lewis Hamilton described it as no less than the ‘worst looking modification in Formula 1 history’. “I appreciate the quest for safety but this is formula 1,” he posted on Instagram, “and the way it is now is perfectly fine.”

Things have changed since then, however. After watching an FIA submission on the Halo on the eve of the Hungarian Grand Prix, Hamilton is now a believer.

Nico Hulkenberg is one driver who doesn't look like coming around to the FIA’s way of thinking, however: “I don't like how it looks and for me it feels like trying to eliminate every little bit of risk.”

One big concern yet to be addressed is accessibility in a variety of accident situations. For one, it’s hard to see how it wouldn't have hindered Fernando Alonso as he extricated himself from his upside McLaren at Albert Park this year. From what we do know about the design, you wouldn't want to be upside down and on fire with a Halo.

Nor is it likely to prevent an errant small component from entering a cockpit, such as the steel spring which smashed Felipe Massa’s helmet in 2009. That level of safety certainty can only be achieved with a full cockpit shroud, in the style of LMP1 sports cars.

That may well be a bridge too far. In any case, Toyota LMP1 driver Anthony Davidson reckons a full canopy wouldn’t offer full protection: in sportscar racing he’s seen them break.

As an ex-F1 driver, Davidson has strong views on the Halo idea. He’s a fan: for Davidson, the only point of contention is the extent to which the driver’s forward visibility is compromised. The argument about aesthetics, or that it goes against the essential essence of open-style racing cars, just doesn't wash, he told journalist Will Buxton.

“I’ve really thought long and hard about it, and I think it is the best solution for now… No one person has got an ideal solution to the problem. All I know is that the argument for not having one doesn’t hold. ‘It doesn’t look very good’. ‘F1 cars have always been open cockpit’. I’m sorry but that’s not enough for me, for things to carry on this way.”

Whatever anyone thinks about the Halo (or whatever type of overhead cockpit device we end up with), what we’re discussing here could prove to be a landmark point for safety in the sport. It could be that we have arrived at the logical, inevitable end-point of the long evolution of safety in F1. That’s not to say that risk will ever be eliminated, but the cars, the circuits, the driver apparel, the HANS devices, the administrative systems in place such the Safety Car and Virtual Safety Car – in so many areas F1 and motor racing overall is so much safer than it’s ever been. Recent history suggests that helmet impacts now represent the single most dangerous aspect of openwheeler racing – and now it is being addressed.

Over the past half-century there’s been enormous progress made in the area of safety. Anyone of the view that motor racing is in danger of sanitising itself should first remind themselves that this sport has a gruesome history.

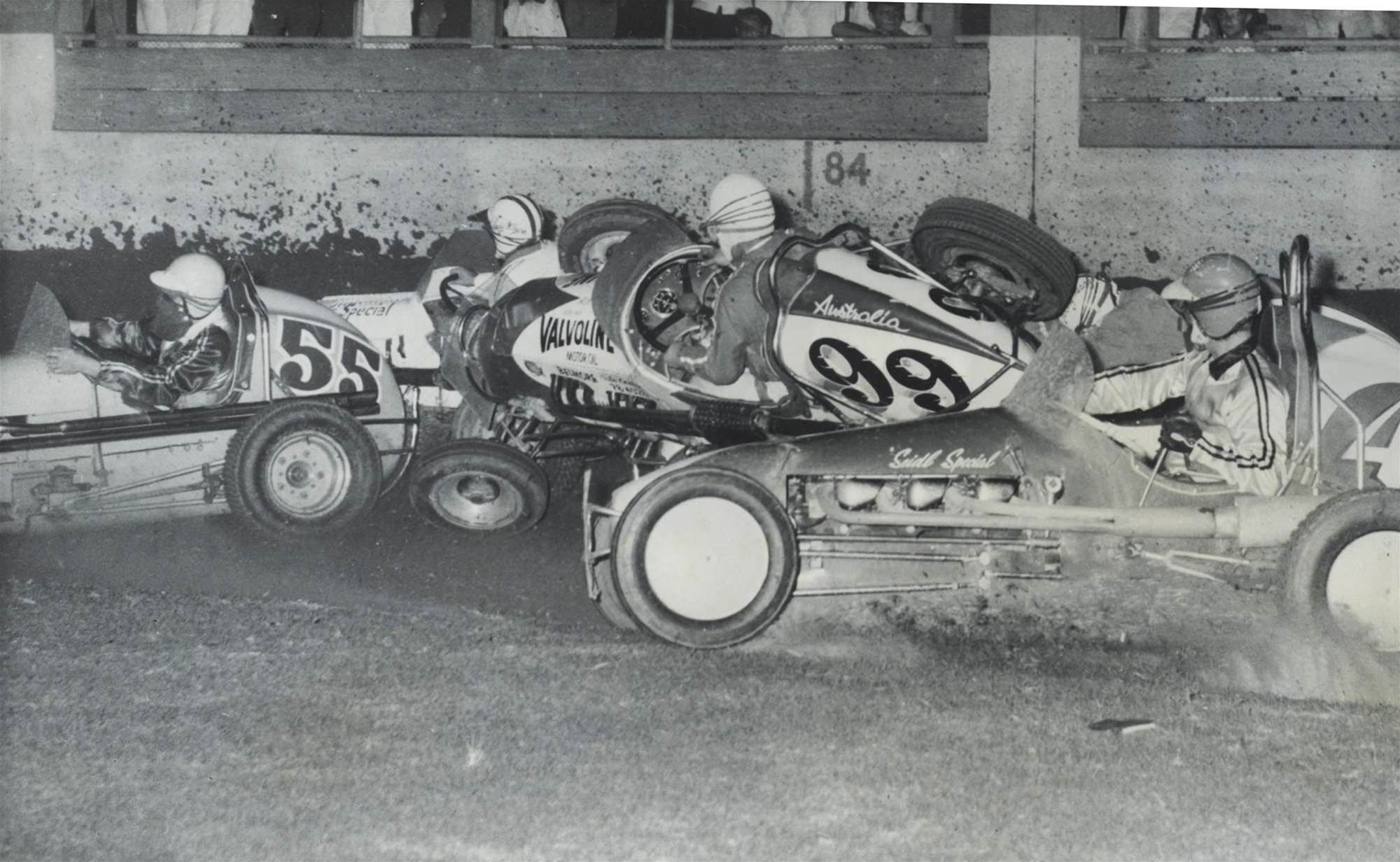

Consider what used to happen in speedway racing in the 1960s. Speedway at the time was probably more dangerous than anything else in the world of four-wheeled motorsport. Death and serious injury were often week-to-week occurrences. Speedcars did not have proper rollbars (nor did the road racing openwheelers of the day, for that matter), much less rollcages. In NSW, a well-meaning but horrendously misguided act of parliament (the 1957 Speedway Act) allowed speedway racing to be run at showgrounds that used traditional country-style fencing with exposed upright posts with wire cabling running through them. Most of the speedway venues of the era were of this type. Year after year, drivers and riders were routinely skewered on these fencing uprights (this inconceivably sorry state of affairs went on for years and was only rectified after Mike Raymond pressured the government into action through his daily newspaper speedway column).

Yet even then, when it was proposed that the sport mandate full rollcages in an attempt to reduce the carnage, many drivers were vociferous in their disapproval.

The arguments back then have a familiar ring today. Cages would spoil the look of the cars, they said. Midget Speedcars had never been fitted with cages in 50-odd years of speedway, so why start now? Then there was the question of bravery: that to race with a cage was the coward’s way.

In the end the pro-cage lobby won. The adoption of cages has proven to be probably the biggest single change in the history of speedway.

It certainly changed the way the cars looked – those who warned cages would spoil the appearance of the cars sadly were proven all-too correct. As the caged era took hold in the 1970s, and designers started to integrate cages into the chassis structure rather than treat them as bolt-on safety bars, speedway openwheelers gradually shed their classic svelte roadster lines and morphed into stumpy, box-like structures on wheels.

But the trade-off was a dramatic and immediate fall in the death and injury toll.

As for the ‘cowardice’ issue, not even the bravest, or most foolhardy of today’s drivers would even think of racing a speedway openwheeler without a cage.

One thing that we have learned from history is that, over time, attitudes can shift dramatically. Over the last four or five decades, the level of what’s considered acceptable risk in sport – in the eyes of both the public and the participants – has reduced substantially. Any mainstream sport today to incur the kind of death and injury which motor racing did in the 1960s would be the subject of widespread public outcry – and would likely be shut down for good.

So, how will the next decade and beyond look? In 10 years’ time will we look back, shake our heads and wonder how we ever allowed openwheelers to race with drivers dangerously exposed in open cockpits? Or will we rue the day they fitted overhead cockpit safety bars to F1 cars, and yearn for the bygone era of the classic, uncluttered lines of traditional open cockpit racing cars?

Or might we reach the same conclusion that so many fans, commentators and past drivers did when they watched this year’s British Grand Prix start behind the Safety Car (and then continued to watch in mounting frustration and incredulity as the cars trundled around behind the Safety Car for so long that the track began to dry and half the field were in the pits for intermediates before the authorities were bold enough to allow the drivers to actually race their cars), that motor racing has lost the plot?

“If they are afraid, they should go and race touring cars”

During his time in F1, Jacques Villeneuve more than once expressed annoyance over attempts to make motor racing safer by introducing longer runoff areas and other measures.

He famously criticised safety improvements at Spa-Francorchamps, saying that F1 was being sanitised and gradually being stripped of what he saw as an essential part of the sport, the element of danger. It was a stance he maintained consistently throughout his career and beyond, in spite of the fact that his famous father, Gilles, met a violent death at the wheel of an F1 car.

No prizes for guessing what Jacques thinks about the Halo, then.

"If they are afraid, they should go and race touring cars," the 1997 world champion told French newspaper Le Figaro earlier this year when quizzed about the Halo concept. "Yes, we must strive for safety, but there are limits we should not exceed. Risk-taking is inherent in F1. It's part of the beauty of the sport…

“I see it that these drivers earn millions and yet they do not want to take any chances. Too bad.

"Do the MotoGP riders ask to ride inside a bubble? This is why they are increasingly respected and admired compared to Formula One drivers."

Remove the element of danger from motor racing, according to the likes of Villeneuve, and you are left with nothing. It’s the notion that the challenge of facing up to real danger is fundamental to being a racing driver – to be not merely the fastest and most skilful, but also the bravest. It’s this aspect that sets motorsport apart from most other sports: the idea that a racing driver is closer in nature to, say, an aircraft fighter pilot than a participant in a sport.

It’s a romantic, old-world view of the sport which was given expression by literary giant Ernest Hemmingway in this famous quote: “There are only three sports: bullfighting, motor racing, and mountaineering; all the rest are merely games.”

Perhaps the question motor racing needs to ask itself is this: should there be an acceptable level of risk? And if so, what is it? And does it matter whether motor racing today is a sport, according to Hemmingway’s definition, or merely a game?

Safety first

On Friday at the Hungaroring on the weekend of the Hungarian GP, one week out from when the top teams were set to vote on the Halo, F1 drivers were given a presentation from the FIA on the Halo concept.

The presentation examined past accidents in F1, GP2 and GP3 and put the case as to how the Halo might have behaved in each situation.

After viewing what were reportedly ‘shocking’ images, some F1 drivers previously opposed to the Halo concept have changed their views.

For Lewis Hamilton, whose initial responses to the Halo included ‘Please no!’ and ‘if it does come in then l hope that we will be given the option of not using it because l will not be using it on my car’, the Hungary presentation has been something akin to a Road to Damascus experience.

"I take safety very seriously and I think the interesting thing,” he said, “while it doesn't look great and doesn't look in the racing spirit, you can't ignore the fact that the chances are 17 percent better of saving a driver's life in the incidents that have happened in the past.

"However, we still have to continue to improve and at some stage we would have to close the canopy completely because that would be 100 percent. There were still some examples, like Felipe [Massa]'s accident here in Hungary in 2009, where it wouldn't have stopped him from being injured. I think with Justin [Wilson's Indycar accident], I believe they said it wouldn't have saved him because it was a pointy object from above, but a closed canopy would have perhaps.

"You can't completely ignore it. If there is any way to make it look a little bit better then fine, but if not then it's a safety thing which we have to accept."

Whatever the relevance of the aesthetics argument, this is one area where the Halo seems utterly friendless (outside of perhaps its creator and the FIA).

Aesthetically no one likes it,” Carlos Sainz said, “so we need to balance how much is worth it to save a life per five or 10 years against how bad the repercussion against Formula 1 is.”

Sainz’s Toro Rosso team-mate Daniil Kvyat remained unconvinced after the safety presentation.

"The arguments they gave us regarding safety were strong. They gave us cases of when the wheel comes off, when you do this or do that. Obviously if you really want we can make F1 completely sterile and completely safe – but the question mark is where we need to stop.

"I don't know if it is already a step too far or we have just reached the borderline with the Halo. I might be playing with the devil and I have said many times that when I come to the race track, I know that it might be my last day in the office.

"…I am not trying to be a hero or anything but in the end we are also racing for other people and in the end F1 is a show. But that is why it is so popular."

Related Articles

Norris tops day one in Bahrain as Red Bull’s straight-line edge draws attention

Gallery: McLaren MCL40

McLaren's 2026 livery launch

Latest News

Gallery: 2026 TCM Sydney Motorsport Park

How the 2026 Bathurst 12 Hour will be remembered

Norris tops day one in Bahrain as Red Bull’s straight-line edge draws attention

Most Read

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)

New F1 magazine launches in Australia for 2026

How the 2026 Bathurst 12 Hour will be remembered

Checo Pérez and Valtteri Bottas return to the grid with Cadillac for 2026