Malawi-born world champion Cate Campbell will be on our side at the Comm Games.

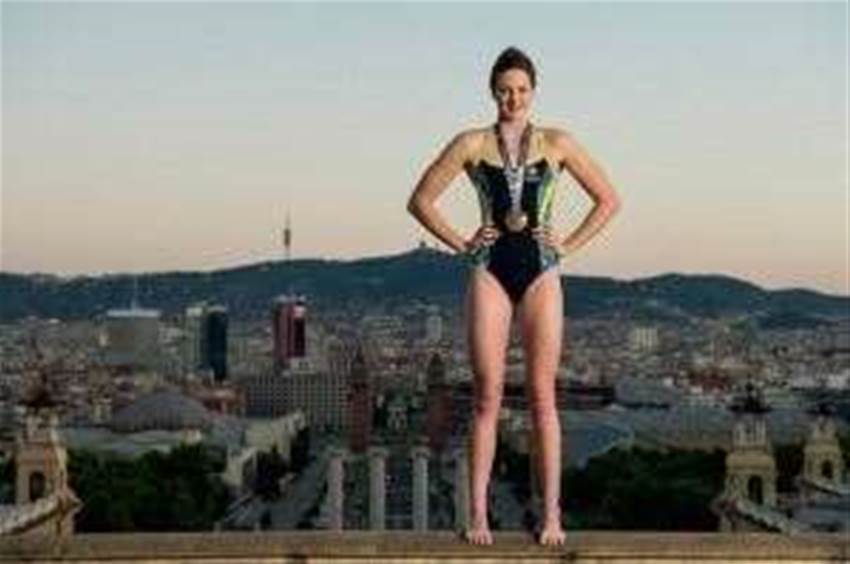

Cate Campbell conquered Barcelona, and the rest of the swimming globe, at the Worlds in 2013. Photo: Getty Images.

Cate Campbell conquered Barcelona, and the rest of the swimming globe, at the Worlds in 2013. Photo: Getty Images.IT’S LATE FEBRUARY, and the world’s fastest woman in the water is transfixed by the speed and skill to be found in her counterparts on the ice. “I’m obsessed with the Winter Olympics,” replies Cate Campbell, close to bubbling. Early-morning pool schedules allowing, the dual Olympian has been taking in as much of Sochi’s various slopestyles and slaloms as she can. Every triumph resonates, every slip elicits sympathy, all amplified by the four years of toil that Games competitors are made to wait. “That’s just what is so nerve-wracking about watching these events,” Campbell observes. “Fortunately for us, if we make a mistake, we don’t have to fall ten metres and land on some icy snow.”

There is, undoubtedly, a collegial spirit at work, a vision of her own moment to come. “It’s one of the most amazing things to see someone’s dream achieved. How often do you get to witness that moment in someone’s life? It’s so inspiring, so exciting, so nail-biting.” She laughs. “It’s stressing me out.”

It’s hard to fault Campbell for being excitable as she looks to her season ahead, or to even fast-forward the next couple of years to Rio. She stands tall, rather literally, among the swimming world’s elite in the sprints, the current world champion in the 100m freestyle and no.2 in the 50m free, accomplished last year in Barcelona. With James Magnussen’s corresponding win, Australia claims both of the leading figures in the pool’s blue-ribbon event, a first since the era of Dawn Fraser and John Devitt’s victories at the 1960 Olympics. Last February, Campbell was named Swimming Australia’s swimmer of the year.

It’s a status that seemed foreordained when she first emerged at the 2008 Olympic trials as a 16-year-old, finishing second in both sprint swims to a world record-setting Libby Trickett. In Beijing, Campbell beat Trickett to claim bronze in the 50m, and the hand-off from one generation’s star to the next appeared complete.

What happened next was rather unexpected. In one respect, it had the attributes of a 100m race: a flying start, an immersion, a tumble, a turn ... and then what? Campbell is talking technique, but could be speaking metaphor: “You don’t want to get up behind the block when you’re fully tapered and dive in the water, and be like ‘this is amazing’ – and take it out way too fast. “You want to know how fast you can go out, and still be able to come home at a respectable pace.”

**********

ONE ENTRY in the Cate Campbell bio immediately jumps out: Malawi. The landlocked nation at the southern end of the East African Rift is one that doesn’t figure too often in the origin stories of Olympic champions. A longitudinal sliver wedged between Tanzania, Zambia and Mozambique, a fifth of the country is covered by a lake known either as Malawi or Nyasa, and is one of the great lakes found in the Rift Valley: only Victoria and Tanganyika are larger, and the latter is the only one deeper.

Beyond geography, the lake is the dominant feature in the cultural life of Malawi: source of commerce and recreation, common point of reference, vital resource to the storehouse of scientific knowledge. Like the Galapagos Islands, the lake is one of the prime locations in the world for studying evolutionary development – the diversity of Malawi’s cichlid fish is an example of how species adapt to differing environments. The colourful fish have become central to the lake’s character – seen from space, Lake Malawi even looks like a flapping fish.

The highlands south of the lake, just below the fish’s tail, have been an area of European settlement since the 19th century. The famed explorer David Livingstone helped establish a British presence – the main centre of Blantyre was named after Livingstone’s birthplace in Scotland. Malawi became independent with the end of Britain’s African colonies in 1964 and distinct from its neighbours was the only African country to maintain diplomatic relations with South Africa during the apartheid period. The two countries have a history of exchange, which included Campbell’s parents, Eric and Jenny, who left South Africa after Eric took a job with a bank in Blantyre.

That teenage prodigy is now one of the most intimidating presences in the pool. Photo: Getty Images.

That teenage prodigy is now one of the most intimidating presences in the pool. Photo: Getty Images.Cate was the eldest of five siblings born in Malawi, and bears memories of a place both strikingly different yet supremely bucolic. “Growing up in Africa, it’s the funnest place to be a kid,” Campbell says. “I almost want to go back and have my kids in Africa, because I had so much fun.

“I have very fond memories. It’s definitely given me an appreciation for what I have now. I’ve seen what people with nothing look like, and how happy they can be. I think I’ve been given so much and been blessed in so many ways, I have no right to be upset.”

The Campbell kids enjoyed an upbringing that was appealingly rustic: surrounded by pets, they spent their time collecting the eggs from their chickens and chasing their guinea pigs. Cate devoured books: classics, historical fiction, Jane Austen and the Brontes. Family trips were spent at cottages by the lake, and the Campbells’ connection to the water ran deep – Eric was a sailor, while Jenny had competed in synchronised swimming, and was the one who would encourage her children to dive in. Where Australian youths take to the surf hearing cautionary tales of great white sharks, Cate and her siblings were raised on warnings about hippos.

“Some of my earliest swimming memories are paddling in the shallows there; most of the photographs of me are when I’m holding mum’s hands and paddling in the lake,” says Campbell, recalling how her dad would participate in Lake Malawi’s Marathon, the noted week-long sailing race. “All the sailors would sail the length of the lake. Mum, being the wonderful, selfless woman she is, would let Dad gallivant out on the lake while she drove the pothole-ridden roads with the trailers and three or four kids in the back.”

Campbell was nine years old when her family made the decision to move to Australia, settling in Brisbane. The culture shock was a given; what’s more, she notes, moving to this new country was also her first experience of going to school, having previously been homeschooled. “Until we moved to Australia, I’d only been to Malawi and South Africa. I came from a town where there was one traffic light, and you were lucky if that worked. My earliest memory of Australia was walking around saying, ‘It is so clean.’ The roads were all tarred. The lack of poverty struck me. I thought this was a wonderful place.”

Suggest to Campbell that her situation sounded a bit like the plot of the Lindsay Lohan movie Mean Girls, and she laughs.

“At first, it was tough; I was this tall, skinny, pale girl with a strong South African accent” – the lilt of which is still distinct. “Very awkward social skills. It took me a while to find my feet, but I found my niche, found friends I could relate to. Fortunately I didn’t have to contend with the mean girls ... ”

Swimming would prove to be a place where the young Campbells could speed their assimilation. Cate, with sister Bronte, found her way to Simon Cusack at the local club in Indooroopilly, and he remains their coach to this day at Brisbane’s Commercial Club. Cusack couldn’t help but notice the different provenance of this pair, once remarking that they were just more resilient than the typical Australian kid beginning the hard slog that leads to glory in the pool.

Like other Australian sports suffering recent downturns, swimming has been caught up in a rather sweeping critique of Gen-Y shortcomings. The case of the Campbell sisters certainly provides more fodder – the material for the classic, hard-going Aussie swimming champion had to be sourced out of Africa. Campbell admits to a bit of mystery in her relationship to her sport. Her own evolution as a swimmer has been as random, as subject to external forces and factors both large and small, as the fish in Lake Malawi.

“When people ask me what I love about swimming, I’m not exactly sure,” she says. “Being good at it definitely plays a role; you usually love what you’re good at. But even as a youngster, I remember spending hours in the pool. When I was 12 or 13, I would ask my coach if I could do some more sessions.

“When you compete, you get to see, hopefully, the fruits of your labour, that direct correlation between hard work and outcome. I love that correlation.”

**********

THAT LOVE would be tested in the period after the Beijing Olympics. After another bronze at the Worlds in Rome in 2009, Campbell’s next two years were derailed by illness. Glandular fever, which led to chronic fatigue syndrome in the aftermath, caused a serious drop in Campbell’s form. The girl known throughout school as the swimming champion began to question her identity. “I couldn’t understand why I could go low 24s as a 15-16-year-old, and then as an 18-19-year-old really struggle to break the 25-second barrier,” Campbell says. “Was it a fluke? Was I just one of those child wonders that flared briefly?

Cate and Bronte's sister act is getting rave reviews. Photo: Getty Images.

Cate and Bronte's sister act is getting rave reviews. Photo: Getty Images.“All I knew was that swimming was what I was good at. And suddenly, I wasn’t good at it anymore, and it was very frustrating and confusing. But in saying that, I learned so much about myself, and became closer to my friends, my family, my coach. I discovered I could exist quite happily without swimming, and I think it’s given me good perspective. Now I think, ‘This is what I love to do, just enjoy it because it’s not going to be around forever. You know you can survive without it, but life’s a whole lot better when you’re swimming, competing and enjoying it.’

“I don’t think there was ever one moment when I realised how much swimming meant to me, or that ‘yes, I’m better now’. I was gradually getting better, it took patience.” She laughs again, although more ruefully. “They say patience is a virtue, and I’m very virtuous. It taught me a lot. I wouldn’t recommend it; maybe learn off my experience rather than going in and experiencing it yourself.”

The 2012 Olympic selection trials in Adelaide were dominated by the narrative of big-name comebacks: Thorpe, Trickett, Huegill, among others, seeking one last splash. Campbell was devising a return of her own, and had to contend with a sprint field that had filled with contenders during her two years away. She ended up qualifying for both of her events, though, and came away from the trials at the centre of another neat and irresistible storyline – with Bronte finishing just behind her in the 50m, the Campbells became the first sisters to compete in the same Olympic swimming event for Australia.

The London Games hit depths of infamy that inspired all manner of navel-gazing, soul-searching and official-reviewing for the nation’s swim team. Campbell, however, didn’t have much time for other peoples’ problems; she had her own to deal with. The program started ideally – on the very first night she won gold as part of the victorious 4x100m free team, swimming the third-fastest split of the final.

Two days out from the 100m, Campbell woke up at 5am feeling nauseated and went to see the team doctor, who diagnosed her with food poisoning. Campbell went back to bed, then woke up again “with the most excruciating pain radiating from my stomach and lower back”. “I staggered out to the bathroom thinking I needed to vomit again. Turns out I didn’t, and I just passed out on the floor. Woke my sister up with a loud bang, because there’s a lot of me to hit the ground. She came staggering in and found me lying on the floor.”

It turned out to be pancreatitis, although it wasn’t confirmed for another couple of days. The cause was viral, just one of those things that can happen when you cram 10,000 people from around the world into the same space. Campbell missed the 100m, and had the doctors known about the pancreatitis sooner, she would’ve been held out of the 50m, too. Having already qualified for the semis, she went ahead and raced, missing out on the final. “The two weeks of the year I needed to stay healthy, I contracted this virus. It was devastating.”

Photo: Getty Images.

Photo: Getty Images.Campbell remained one of the swimming world’s most tantalising cases of if-only. With her 186cm frame and long pull through the water, she has the physical tools that set her apart. At top speed, she’s the type of racer who can leave her peers gushing. Campbell’s focus in training has been to add strength, which would allow her to use her long levers to full effect – able to swim freestyle, as she has explained it, more like a man would.

Free from her maladies, she had an ideal preparation before arriving at the 2013 Worlds in Barcelona. There were early signs at the Palau St Jordi, which was the venue for gymnastics and basketball – and not swimming – during the 1992 Olympics. On the opening leg of the 4x100m relay, Campbell recorded a 52.33 split, the second-fastest time in history. The mark of 52.07, held by Germany’s Britta Steffen, was set in 2009 when the super-suit was shredding the record book.

Taking care to avoid any unhealthy situations over the following week, Campbell qualified second for the 100m behind Swede Sarah Sjostrom. In the final, she went out at a cracking pace, 0.61sec ahead of the world record. She held on to finish in 52.34, just in front of the fast-finishing Sjostrom, as well as Olympic champ Ranomi Kromowidjojo and American star Missy Franklin. Steffen’s time, once thought to be safely beyond reach in the textile suits, now seemed a realistic target.

For her part, Campbell was thinking less about the time and more about hitting the wall first. The plan for a major meet had finally gone off. “It went as close to perfection as you can get,” she says. “It was a fun meet, there was a great environment in a beautiful city, it was a great place to be a spectator as well as a competitor.”

It also happened to be Campbell’s first time visiting Europe. Fittingly, for a new world champion, she was able to take advantage of it. “Bronte and I stayed over for an extra two weeks and did a little backpacking tour. We stayed in Barcelona for an extra few days, then we went to Madrid, then a tour of Italy down to the Amalfi coast. We kind of figured that we wanted to do that, thinking why fly all the way home then all the way back?”

**********

CATE CAMPBELL began her return to Europe – as did Bronte – in April at the qualification meet for the Commonwealth Games team (Cate pipped her sister in both the 50m and 100m freestyle finals at the 2014 Australian swimming titles in Brisbane). By the standards of sisters engaged in an intensely competitive pursuit, they’re uncommonly close – they live together, even hang out together because, as Cate says, all their friends are at uni during the day.

Sport has long been a useful niche in the study of birth-order dynamics. The most popular theory goes that older siblings turn out more conservative, while the younger ones rebel against the existing structures. In sports, the effects are interesting. A joint Australian-Canadian research project, Pathways to the Podium, found that elite athletes tended to be later-born, motivated by the achievements of their older siblings. (However, it also found that those older siblings often participated in a different sport – part of the younger child’s rebellion was to pick another pursuit.)

In something of an inversion of the theory, Cate has attributed her motivation to Bronte: “It was always Bronte’s dream to go to the Olympics. She was the driven one, she was the one who would get me out of bed in the morning and drag me off to training.

“Then we went to our first swimming carnival. She came away with four gold medals and an age championship trophy. I won a little bronze medal. That’s fine in itself if you don’t have a sister who parades around with the medals around her neck and takes the trophy to the dinner table, and really just rubbed it in my face, let’s be honest here.

“After I had a little meltdown, Mum sat me down and said, ‘You know, Cate, Bronte won those because she works hard. You do not work hard. If you want what Bronte has, you need to work hard.’

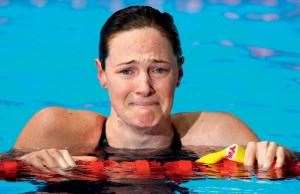

You would cry too ... if you'd just won gold at a Worlds, like Campbell did in Barcelona last year. Photo: Getty Images.

You would cry too ... if you'd just won gold at a Worlds, like Campbell did in Barcelona last year. Photo: Getty Images.“I look back and still remember that moment. I really have Bronte to thank for that. We’re what, now, 12 years on, and she’s still pushing me in training. She’s supporting me, and we’re supporting each other. It’s weird when people ask about sibling rivalry because there isn’t very much between us, at least in swimming.”

In other respects, Campbell describes herself as a typical older sister – she has three other teen siblings, Jessica, Hamish and Abigail, who apparently might be the one to match her in height. “I manage to push the boundaries with my Mum. My younger sister gets away with so much more than I ever could have,” she says. “I was the first, Mum was new to it, I was new to it, and I was a bit of an experiment. But I think I turned out all right.”

With Australian swimming’s new diktat for better internal leadership, Campbell will be counted on to serve as older sister to the team for years to come. As a sprinter, she has a lengthy prime ahead, able to mature over time like competitors such as Dara Torres and Natalie Coughlin. As a face of the team, Campbell will find herself bearing something of the scrutiny that James Magnussen encountered coming into London. Australian swimming will likely figure out that the most effective kind of internal leadership comes from those who are leading at the end of their races.

“What the public often doesn’t realise is just how competitive swimming has become,” Campbell says. “It used to be Australia, America, a little bit of Britain and China. Now we have all of Europe to deal with. And as swimming has evolved into a professional sport, more people are able to concentrate solely on training. Therefore, they’re faster – we’re seeing times that are just crazy.

“It was interesting in London; no single person was the fastest over the 100m and the 200m in any stroke. It goes to show how specialised swimming has become. European countries have more facilities now. We trained at the equivalent of the AIS in Spain before the Worlds last year – it was as good as ours. It’s a country where unemployment is nearly 30 percent, but their facilities rival our own. This just didn’t exist five or ten years ago.”

The new face of the Australian swim team. Photo: Getty Images.

The new face of the Australian swim team. Photo: Getty Images.For a non-Olympic, non-Worlds year, 2014 is shaping up as very full campaign. There’s a Pan Pacs in August, to be held on the Gold Coast, not an hour from where Campbell lives. “To have the home crowd, I’ve never experienced that before,” she says. Before then, the Comm Games will be a key checkpoint for Australian swimming on its bounce-back from the London malaise. By her name alone, the Malawian-born Aussie should find some support among the Scots. “I do know a bit of history around the Campbell clan, and the rivalry that went on with the MacDonalds. My parents toured Scotland on their honeymoon. They went into a bar that said, ‘No Campbells allowed.’” That won’t be likely, one suspects, with the pool in Glasgow.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)