Even modern golf courses are influenced by this great man in one way or another.

THE SCOTS, who enjoy having one over the detestable Sassenachs, can always claim they invented golf – and produced C.B. Macdonald. Old St Andrews dates back to the 1300s. Musselburgh Old Links, we know, was a fully functioning course in 1672, when a lawyer named Sir John Foulis made a diary entry about losing a match there. Apparently, if rumour is correct, Mary, Queen of Scots played there almost a century earlier, in 1568.

Courses like those at Musselburgh and St Andrews weren’t designed in the sense we know them now, simply because the nuances of the game had not yet developed. “Environment”, while a consideration, was not viewed in today’s sustainable, conservationist way, and the technology that enables modern golfers to hit balls further and with greater accuracy, like titanium heads, hybrid clubs, perimeter weighting and cavity design, was still a long way off. These courses “evolved” out of the dunes, and even the fairways “emerged” with wear.

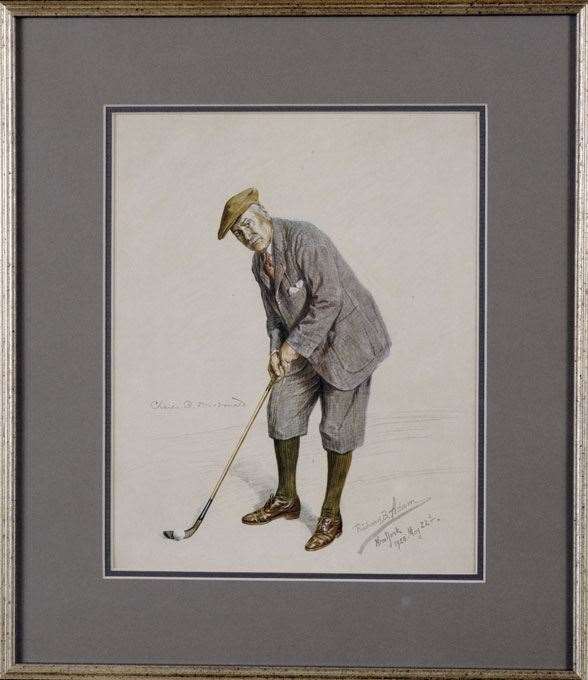

But it still took a man of Scottish heritage on his father’s side to pioneer course design as we know it. This intelligent, restless, opinionated and irascible father of American golf course “architecture”, as it’s called, was really the father of the science and art of course design. Charles Blair Macdonald constructed the USA’s first 18-hole course (there were a few rudimentary nine-holers around) in Chicago in 1892.

Macdonald was uninterested in golf until, at 16, he was sent from Chicago to St Andrews, where his grandfather lived, to be educated. Macdonald was captivated by the game’s challenges and the fascinating courses it was played on. He took it up and was soon playing against some of the best of the era, like Old and Young Tom Morris, the Dunn brothers and David Strath.

In 1908 he founded what is today called “the snootiest golf club in America”, the National Golf Links of America on Long Island. His design was pure imitation, but, after surveying the best British players of the era to find out the “best and most difficult” holes they’d played, he created a course that compared favourably with, and in some cases even exceeded, the originals.

Being a pioneer, he was learning about design as he went. In the end, he was able to develop measurable criteria for laying out a championship course, assigning “merit” point percentages to certain “essential characteristics”, which helped his thinking about the length and sequence of holes. His challenge was to ensure his imported holes still suited the terrain on Long Island. The National soon became known as the best, and toughest, course in America.

Macdonald repeated this formula as he went on to design numerous other courses, but The National was his pet project; he would continue to make loving tweaks to its layout for the rest of his life. Even today, the course, which hosted the inaugural Walker Cup in 1922, is considered a benchmark of golf architecture. Macdonald set the scene for future designers such as Tillinghast, Mackenzie, Ross, Jones and others, right through to the giants of design today: Nicklaus, Dye, Fazio, Doak and the duo of Coore and Crenshaw.

After WWII, heavy earth-moving equipment enabled designers such as the legendary Robert Trent Jones to create water hazards that were once only a feature if they occurred naturally. The most spectacular examples are hazards like the 4th at Baltusrol Lower and the 16th at Oaklands Hills. Or the island green on the 16th at the Golden Horseshoe.

Course design has developed to such an extent that it even has its own controversies. Today, opinion is split as to whether one should have a “signature” designer or a course architect design their course. Nicklaus, Palmer and Player are businesses now, and the golfing world is dotted with their creations. But purists will tell you the architects do all the work. As with the many engineers involved in the innovations we have covered in this column, these architects often remain anonymous. It’s that classic confrontation between commercialism and pure merit. Jack Nicklaus has been an exception. The Golden Bear is a member of the Golf Course Architects Society of America, which requires a demanding application process. He has three courses in Golf Digest’s Top 100. The only other tour pro to challenge him is Ben Crenshaw, widely regarded as a great architect following his partnership with Bill Coore. The best pro golfers-turned-designers are those who work with architects, leaving the maths, the art and often the science to them, while they apply their practical knowledge to design once they see it.

As with any pursuit, design has occasionally gone too far and allowed for the incursion of a phenomenon commonly referred to as the Artistic Wanker. We’ve had courses that are almost impossible for the golfer to figure out, let alone play, as Freudian, postmodernist and even surrealist influences have affected design.

Some of the best architects today create courses comparable in aesthetics to the great works of famous 18th-Century landscape artists, like Capability Brown. Like any artist, the modern designer has benefitted from technology and the possibilities it’s opened up. No 19th-Century designer would have wandered out into the most inhospitable desert on Earth with a millionaire, as Tom Fazio did with casino mogul Steve Wynn to build Shadow Creek in Nevada in 1989. They moved in the graders and dozers, had the soil analysed, dug a hole 20 metres deep and one kilometre square, and created a facsimile of the North Carolina Sand Hills, complete with swamps and alien vegetation.

Even the humble, idyllic golf course has come a long way since C.B.

Related Articles

Morri: Golf at Riviera is golf worth watching

Review: Titirangi Golf Club