Criteria seems out of step with realities of today's game.

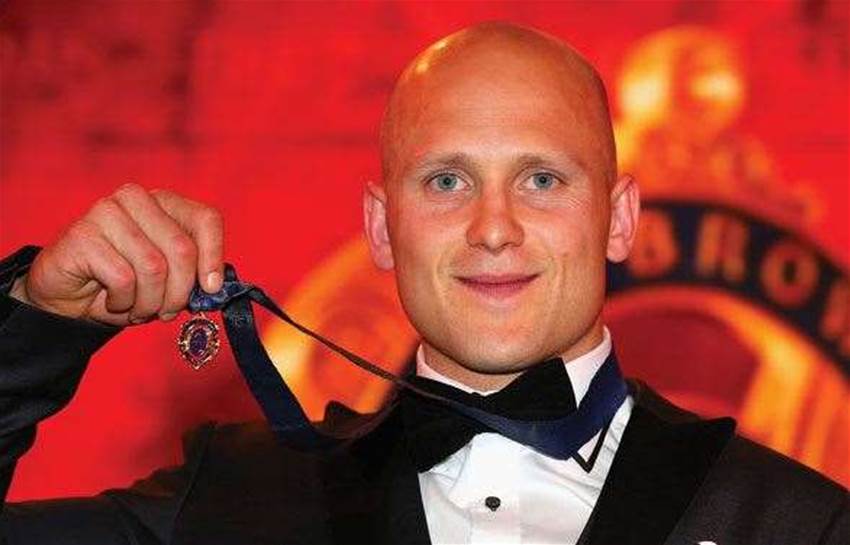

Gary Ablett Jr might win the Brownlow even after being out injured for the final seven rounds. (Photo by Getty Images)

Gary Ablett Jr might win the Brownlow even after being out injured for the final seven rounds. (Photo by Getty Images)The first Brownlow-medallist, Carji Greeves of Geelong, seemed to have the honour well and truly sized up. “Carji always used to say,” his late widow Alma recalled in the book The Brownlow, “the fairest side of it was the hardest.”

It could be taken as commentary on the rugged nature of Australian football. Or perhaps a meditation on the true essence of sporting class. Either way, the spirit set forth in the Brownlow’s citation – for the “fairest and best”, and note the order of priority – has shaped the ideal of the champion footballer since. It is not enough to be the outstanding performer afield; one also has to be a prince among men (or, at least, someone who can be a gun and avoid getting reported at the same time).

Best-and-fairest has become a distinct piece of Australiana. Look at other nations’ sporting cultures, with their various men-of-the-matches and MVPs, and you see a different viewpoint at work. Recognition of individual brilliance is much more mechanistic: the best or most well-regarded player, as measured by the stats and the ratings. The idea that a person’s character should factor into deciding these awards is as old-fashioned as, well, something that originated 90 years ago.

In the context of a modern, forward-looking sports league, the AFL’s most esteemed individual honour – and, by extension, one of the biggest in all of Australian sport – is showing signs of conceptual strain. Its foibles and biases are well-known: that umpires still do the voting, that the ever-more elaborate tribunal process can rule a worthy player ineligible, how talented sets of team-mates steal votes from each other, the over-representation of on-ballers among the winners, and perhaps worst of all, the list of genuine greats (Whitten, Matthews, Ablett the elder, Carey) missing from the roll.

This season could present the most convincing case yet for Brownlow reform. Gary Ablett Jr, perfectly placed in his Gold Coast set-up for a historic chase at a third then possibly a record fourth Brownlow, might be able to win despite missing the last seven rounds to injury. This was only after he was cleared of elbowing the Bulldogs’ Liam Picken, an incident that was immediately framed in terms of Ablett’s Brownlow chances. Fremantle’s Nat Fyfe, a classic polling machine of a player, has also had a superb year but is already disqualified because of a two-match suspension, which stemmed not from some act of malice, but that most present-day transgression, the high-contact bump gone wrong. Both situations, and the chatter that surrounded them, highlighted how the Brownlow’s criteria seemed so out of step with the realities of today’s game.

Consider, however, the proposition that the Brownlow has survived as long as it has because it is an anachronism, and a charming one at that. That it has become a focal point for a breathless footy media, and the ceremony itself Melbourne’s ersatz Oscar night, are window dressing. It has remained relevant because the count itself has all the best qualities of a great footy match: tension, surprises and great names emerging at the end. It might not be the most appropriate way of recognising the finest player in the AFL, but once you can accept that premise, it becomes easy to see the Brownlow for what it is – an historic and prestigious, but not necessarily foremost, prize. And there’s nothing unfair about that.

He didn't win a Brownlow, but Leigh Matthews did get a statue at the MCG ... (Photo by Getty Images)

He didn't win a Brownlow, but Leigh Matthews did get a statue at the MCG ... (Photo by Getty Images)THE ALTERNATIVE BROWNLOW ...

In a 1999 newspaper poll to determine Australian football’s player of the century, Leigh Matthews emerged as the leading figure, and as footy doyen Mike Sheahan observed, the acclaim gained near-universal acceptance. But it’s part of the hard-edged Matthews’ legend that he could never win over the umpires during his brilliant career, with third-place finishes in 1973 and 1982 the best he ever did on Brownlow night.

Fittingly, Matthews’ name has become attached to the alternative Brownlow. The Players Association has given a most valuable player award since 1982, and its first winner was none other than Matthews. In 2002, the award was renamed in his honour. While similar in concept to MVPs in other pro sports leagues, which are determined by a select group of media, the Matthews Trophy differs in who votes for it – it’s decided by AFLPA members, who each cast a vote (as always, three-two-one) from a shortlist of 51 players, three from every team excluding their own.

The MVP, perhaps as reflex to that other medal, has recognised the key-position likes of Jason Dunstall, Gary Ablett Sr, Wayne Carey and Nick Riewoldt. Its own stature within the game is building, even if there is a growing realisation that players are as guilty of their own kind of groupthink as the umpires – the younger Ablett has now won five of these, including last year’s by more than a thousand votes.

About the only issue with it is the name – where “the Brownlow” sounds venerable, “the Matthews” is somewhat flat. Academy Awards came to be known as Oscars because a noted Hollywood columnist used that name to mock them. Anyone for calling the MVP “the Lethal”?

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open