In the rollcall of champions from Australia’s Golden Era of sport in the 1950s and ’60s, the name Ken Rosewall inevitably arises.

In the rollcall of champions from Australia’s Golden Era of sport in the 1950s and ’60s, the name Ken Rosewall inevitably arises: eight Grand Slam tennis titles will do that for you.

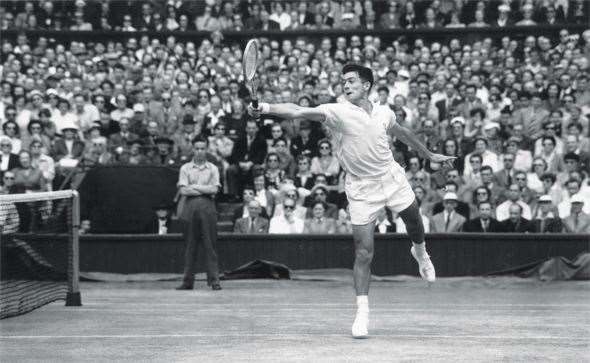

Balls above shoulder height stretched “Muscles”, but it wasn’t just about

Balls above shoulder height stretched “Muscles”, but it wasn’t just aboutpower in his day. Image: Getty Images

Roswell is usually mentioned behind the likes of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad and Roy Emerson: despite reaching the Wimbledon final four times, it was the one grand slam title that eluded him. And 11 years playing on the then-fledgling professional tour, when he was at the peak of his powers, precluded him from competing at the Championships (before the Open era), leaving it the one and only gap on an otherwise stellar resume. But for sheer longevity and consistency, Rosewall probably has no equal: he won his first Australian Open in 1953 at age 18, and his fourth in 1972; he was first a finalist at Wimbledon in 1954 at the age of 19, and appeared in his fourth in 1974 at the age of 39. Tactically he was brilliant at unpicking the games of his opponents, renowned for his metronomic backhand and marvellous court coverage. A new biography, Muscles: The Story Of Ken Rosewall, recounts in fine detail the story of an exceptional player, and a damn decent human being. Now 78, Ken took time out to chat at his Sydney home with Inside Sport about all things tennis.

So Ken, how is your health? You mention in your book the scare you had with a blood clot in your neck last year. Are you back swinging a racquet?

Yeah, I’m all good. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve got busy doing other things. I don’t play as much golf as I’d like and I don’t play as much tennis as I should. I probably play once every couple of weeks.

What sort of racquet do you use when you’re playing these days? From the pictures of you in the book, I can’t shake the idea that you still play with a wooden Slazenger. Or have you moved on to a modern, oversize graphite thing?

Yeah, I’ve moved on a bit. Mainly because they don’t make wooden racquets any more. But I actually switched over to an aluminium racquet in 1971.

Did that make you one of the first to take up the new technology?

There were a few metal racquets around before that, but I was happy playing with the old wooden Slazenger that I started with when I was ten or 11 years of age. But it was a small-headed racquet. It was the big- headed racquets that started making an impact. That’s what really changed the system of playing tennis.

Do you think they might have made the game too easy?

In some ways. It gives you much more margin for error, as you’d expect, and as the metal racquets got better and the strings got better, that’s why we see so much control and pace of the game from the men as well as the ladies. You couldn’t do the variety of top-spin type shots that you see today. When the big racquets first started coming on the market in the late 1970s, it seemed like a bit of a joke, but the official side of the game didn’t really recognise that. They didn’t control the size of the head. There were a lot of people critical of that situation, but now it’s made an impact.

I’d like to test your legendary modesty: I know you’ve received a few honours over the years, but I reckon your achievements are actually under-appreciated by most Australians. What do you think of that statement?

Ah well, I won my few events, and I think I had as many wins against the leading players of the day as losses. But my time was split over a fair number of years, and like some of the other players I played with and against in the earlier pro days, including Rod Laver, we all missed a lot of time on the tennis circuit. I missed 11 years and Rod missed five years. But we thought that we were spreading the word of tennis. We played in most countries around the world and exposed tennis to a lot of people who didn’t know much about the game.

You were a finalist at Wimbledon four times, but it was the one major tournament that eluded you.

Do you reckon that’s the reason? No Wimbledon singles title? Well, that’s always an ambition for any young Australian player, but I felt my record was fairly good there. I was disappointed in the two times I lost at Wimbledon as an amateur.

From left Rod Laver, Rosewall, Tony Roche and Tom Okker act professionally to promote the 1969 BBC World Tennis Championship. Image: Getty Images

From left Rod Laver, Rosewall, Tony Roche and Tom Okker act professionally to promote the 1969 BBC World Tennis Championship. Image: Getty ImagesWere those matches your biggest disappointments?

You were certainly towelling Mr Laver there for a good few years, weren’t you?

You early pros really felt you were part of something back then, didn’t you?

Oh yeah. All of the players worked together. There wasn’t really a lotof money in professional tennis. And to some extent, those of us leading the professional players group had to try and make sure the players below us had enough money to keep playing. So sometimes the reports on how much money you made were a little bit out of line because the money was divided more evenly with all the players in the group.

I read in your biography that you were even chipping in to buy yourselves trophies ...

Well, when Jack Kramer moved out of being financially responsible for the pro circuit, we decided that for us to keep going as a players group, we needed to have an event, like a mini Davis Cup, which we called the Kramer Cup. So quite a few of us put money in to have this gold trophy made in France – it was a really beautiful cup.

And I read you gave that trophy away ...

(Laughs) Yes, one of my worst moves, I think. When the Hunt family started the WCT circuit, I was a strong part of it and supported it because I thought it was great for the growth of the game. But they needed a trophy and so Mike Davies phoned me about the trophy and I said, “Yeah, I’ve got it here in my little office with my feet on it.” It would be very valuable now considering that when the trophy was made, it was $39 an ounce for gold. What is it now – $1800 or something? So the WCT has gone by the by, but the trophy is now on show at the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island.

You said Wimbledon was your biggest disappointment. What’s the one title you won that means the most to you?

So, your first Australian championship?

As an 18-year-old, I was pretty excited about that. I think I surprised everyone, including myself, that I played so well and won the tournament. But the events that really stick in a lot of people’s minds were the first two WCT tours. I played Rod in both those finals in ’71 and ’72. The ’72 final was kind of captured on television.

And Rod was obviously at the peak of his powers then ...

Rod was playing well, though that particular match, I thought his game was very up and down – it had a lot of excitement, that match. The way I played was pretty steady all the way through, so I think I deserved to win the match, even though I was probably lucky to win it in the end.

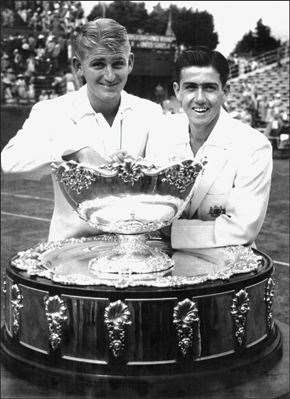

Rosewall and Lew Hoad enjoy the spoils of Davis Cup victory in 1953 over the US. Image: Getty Images

Rosewall and Lew Hoad enjoy the spoils of Davis Cup victory in 1953 over the US. Image: Getty ImagesYou’re well-known for the classy sportsmanship you displayed. Did you ever break a racquet in frustration?

We’ve all had our moments, yeah. Some of the racquets were a little less strong than some of them today ...

I can’t imagine that John McEnroe was the first hothead to come along ...

Well, before John, there was Pancho Gonzales, who was very much his own man; he had a lot of disputes with umpires and linespeople. He was a difficult character in the tennis world – Pancho was a great player, and certainly in my first years as a professional, I found him very difficult to play against, certainly on the fast, indoor-type courts in America.

His gamesmanship too?

Well, gamesmanship to some degree. When he’d get mad, I could lose my momentum or concentration and then he’d come out and play better. I’m not saying he did that deliberately, but that’s the way it worked.

Ever employ that tactic yourself?

No, not really. I was taught by my }father to just get on with the game – you could challenge the linesperson to see if they’d like to change their call, but if they wouldn’t, well, you’d just have to try and get on with it.

You must’ve seen some howling bad calls go against you on some critical points in some big matches. What was the worst call that ever went against you?

Anytime you lost a match, you felt like you got a lot of bad calls. Maybe it was because of me or my attitude, but I think I had my share of good luck with calls.

Do you watch much tennis on television these days?

I pick my matches. I enjoy watching Roger Federer because I think he’s been fantastic for the game both on and off the court; if any young player wanted to have an idol, he’s the man. When you think of what he’s done over a long period of time ... I mean, Roger’s 31 now, maybe 32, and his performances have been good for years. He’s still very hard to beat, and he’s been at the top of the game more or less for ten years. His record is fantastic.

Any women players you make a point of watching?

Well, you can’t go past the Williams sisters – they’re just unbelievable. Their record of what they’ve done – not just in the United States, but around the world. They’re head and shoulders above most of the other women players. Some of them have caught up, but on her day Serena Williams just seems to be so much stronger than the other players at the moment. From an Australian point of view, there’s a bit of pressure on Samantha Stosur, but she doesn’t have as good a technique and overall game as someone like Serena Williams. On her day, Samantha can be good – she is a very aggressive type of player ...

She admits she struggles with home town nerves a bit ...

Yeah, well, some people are like that. I think maybe I went through a little bit of that. In the ’54 Davis Cup, we played in front of a record 25,000 people at White City. For both Lew (Hoad) and I, that was our home town and our home club, friends and family were all watching, and I think I was a little bit overawed that particular day. Lew and I were both very disappointed in the way we played that first day when we lost our singles.

But you didn’t take yourself off to see a shrink the next day?

(Laughs) Ah well, the next day we lost the doubles as well. But I think Samantha might be a little bit like that. Some players perform better overseas – I mean, I won my share of tournaments here in Australia and I won my share overseas, but sometimes my performances here in Australia in those early days were a bit disappointing.

If you had a chance to sit with Samantha, is there any sort of advice you’d offer her?

Well, you’ve really just got to encourage the players. I don’t think there’s anything specific. I mean, she’s ranked highly, but there’s still a lot of girls who think they can beat Samantha because they know some days she’s not as good as she is some other days. She’s either on or a bit off.

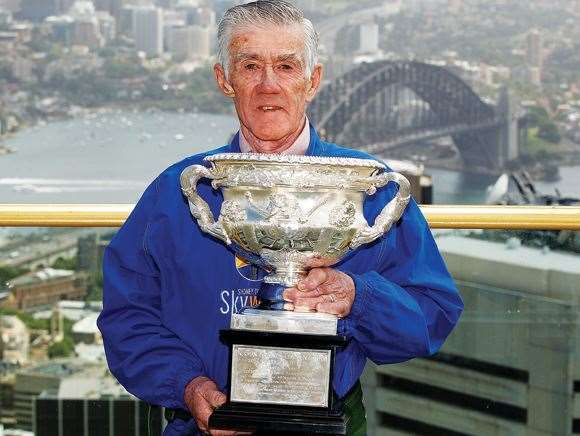

A new biography, Muscles: The Story Of Ken Rosewall, recounts in fine detail the story of an exceptional player, and a damn decent human being. Now 78, Ken took time out to chat at his Sydney home with Inside Sport about all things tennis.

A new biography, Muscles: The Story Of Ken Rosewall, recounts in fine detail the story of an exceptional player, and a damn decent human being. Now 78, Ken took time out to chat at his Sydney home with Inside Sport about all things tennis.Is there any advice you’d like to give Bernard Tomic?

What do you think of the shrieking and grunting that emanates from so many of the top players today? Should there be a law against it? I think an occasional grunt or something like that is alright, but not a continuous screech. Some of the men are making some of the noise as well, but not as much as some of the ladies. But I don’t know whether they can do much about it – they might try to. A few years ago you might remember Monica Seles went through turmoil when they were trying to get her because supposedly she was making a lot of noise, but not compared to some of the girls of today. Whether they can introduce some kind of limit ...

If you’re watching an Aussie Open final and two gals are testing out your eardrums, it takes away your enjoyment of the match as a spectator, doesn’t it?

Well, I think so. Especially if the match is played indoors with the roof closed. I’ve lost count of the number of people who’ve said to me that if they’re watching on television they just turn the volume down.

Do you like the appeal system?

The new technology on line calls? I think people have found that interesting. The players might not have liked it in the beginning, but they’ve adapted to it. The only thing, I suppose, is that it’s unfair for some of the players who don’t get on to the centre court or the number one court very much – if they’re outside and then all of a sudden they’re got to play a match inside, they might get a little bit overawed with that kind of situation. But most of the leading players have adapted to it fairly well.

You suggest in your book that you don’t think someone of your physical stature would cut it in the modern game. Isn’t that a shame about the way tennis has gone?

I don’t think so. But personally, I don’t think I’d be big enough today. Certainly I’d need a lot more physical work to be a bit more muscley. It just seems that with the surfaces they play on, more often than not the balls are bouncing higher, so therefore you’re seeing a lot of shots played at shoulder height. That’s why the two-handed shot on the backhand side is pretty much a dominant shot and you have to use that ... There are a few exceptions, and Roger Federer is one of those. But you have to be an exceptional talent to have a one-handed backhand today.

But you had a famous one of those ...

Yeah, but one of my weaknesses was any shot above the shoulder – either forehand or backhand. And certainly with the older wooden racquet you couldn’t create the power on that high-type shot. In the early days the two-handed shot wasn’t accepted; when my father was talking to me about how I should play, he said, “Well, maybe you should be a one-handed player – you’re giving up a bit of reach being a two-handed player.” Though we had some of the great two-handed players. My idol was John Bromwich in the early days.

Do you think it’s a bit of a shame that some of the subtlety and finesse has given way to the power game?

Yeah, I think you’re seeing too much of the same thing. Once again, you can’t deny the ability of the players, but there’s a lot of power in the game, and that’s changed the strategies of the game to some degree, compared to what some of us oldies played in the early days. Like now, you cannot play a defensive shot, because the ball bounces high as a rule, and the players can move in and just hit it away with their pace. But in the earlier days, maybe you mis-hit a ball and it would go over the net low; especially on the grass courts, it wouldn’t bounce too high, so you’d get a lot more variation in some of the points. But all those things have changed with the hard court surfaces that are pretty much the dominant surface.

Does it sadden you a bit that Australia has slipped so far down the ladder in world tennis?

It does, because tennis has been such a great sport of Australia. And Australians have a great reputation for the record that was created over the years with Davis Cup and winning major events. But those days might never come back because there’s so many good players coming from all over the world. Which is only good for the game.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Feature Story: Moving the Needle