In the rollcall of champions from Australia’s Golden Era of sport in the 1950s and ’60s, the name Ken Rosewall inevitably arises.

In the rollcall of champions from Australia’s Golden Era of sport in the 1950s and ’60s, the name Ken Rosewall inevitably arises: eight Grand Slam tennis titles will do that for you.

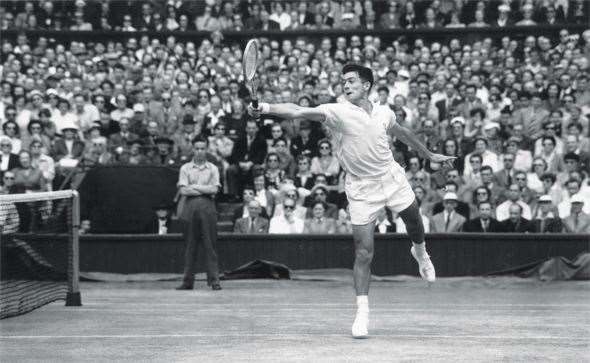

Balls above shoulder height stretched “Muscles”, but it wasn’t just about

Balls above shoulder height stretched “Muscles”, but it wasn’t just aboutpower in his day. Image: Getty Images

Roswell is usually mentioned behind the likes of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad and Roy Emerson: despite reaching the Wimbledon final four times, it was the one grand slam title that eluded him. And 11 years playing on the then-fledgling professional tour, when he was at the peak of his powers, precluded him from competing at the Championships (before the Open era), leaving it the one and only gap on an otherwise stellar resume. But for sheer longevity and consistency, Rosewall probably has no equal: he won his first Australian Open in 1953 at age 18, and his fourth in 1972; he was first a finalist at Wimbledon in 1954 at the age of 19, and appeared in his fourth in 1974 at the age of 39. Tactically he was brilliant at unpicking the games of his opponents, renowned for his metronomic backhand and marvellous court coverage. A new biography, Muscles: The Story Of Ken Rosewall, recounts in fine detail the story of an exceptional player, and a damn decent human being. Now 78, Ken took time out to chat at his Sydney home with Inside Sport about all things tennis.

So Ken, how is your health? You mention in your book the scare you had with a blood clot in your neck last year. Are you back swinging a racquet?

Yeah, I’m all good. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve got busy doing other things. I don’t play as much golf as I’d like and I don’t play as much tennis as I should. I probably play once every couple of weeks.

What sort of racquet do you use when you’re playing these days? From the pictures of you in the book, I can’t shake the idea that you still play with a wooden Slazenger. Or have you moved on to a modern, oversize graphite thing?

Yeah, I’ve moved on a bit. Mainly because they don’t make wooden racquets any more. But I actually switched over to an aluminium racquet in 1971.

Did that make you one of the first to take up the new technology?

There were a few metal racquets around before that, but I was happy playing with the old wooden Slazenger that I started with when I was ten or 11 years of age. But it was a small-headed racquet. It was the big- headed racquets that started making an impact. That’s what really changed the system of playing tennis.

Do you think they might have made the game too easy?

In some ways. It gives you much more margin for error, as you’d expect, and as the metal racquets got better and the strings got better, that’s why we see so much control and pace of the game from the men as well as the ladies. You couldn’t do the variety of top-spin type shots that you see today. When the big racquets first started coming on the market in the late 1970s, it seemed like a bit of a joke, but the official side of the game didn’t really recognise that. They didn’t control the size of the head. There were a lot of people critical of that situation, but now it’s made an impact.

I’d like to test your legendary modesty: I know you’ve received a few honours over the years, but I reckon your achievements are actually under-appreciated by most Australians. What do you think of that statement?

Ah well, I won my few events, and I think I had as many wins against the leading players of the day as losses. But my time was split over a fair number of years, and like some of the other players I played with and against in the earlier pro days, including Rod Laver, we all missed a lot of time on the tennis circuit. I missed 11 years and Rod missed five years. But we thought that we were spreading the word of tennis. We played in most countries around the world and exposed tennis to a lot of people who didn’t know much about the game.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)