Our politicians struggle to find ways to deradicalise Muslim youth ... Maybe they should talk sport.

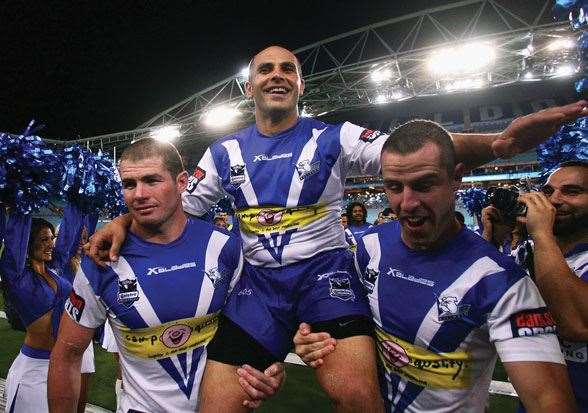

It’s been two decades since Hazem El Masri arrived on the rugby league scene, making his first-grade debut in 1996 for the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs. By the time he retired in 2009 he held the record for the most points scored in the NRL competition. And he also held the distinction of being the first Muslim to play the code at this elite level.

It’s debatable which is the more significant achievement. For many Australians, this country’s Muslim population remains largely hidden from everyday view, except in the context of news reports. When playing for the Bulldogs, El Masri was one of the few Muslims seen by the wider population doing “ordinary” things – though there was nothing ordinary about his footballing ability. El Masri was indeed, as his nickname suggested, “magic”.

El Masri knows what he did. “Mainstream Aussies got to see my honesty,” he says. “Any questions that they had, I was always happy to answer. To get to know each other removes ignorance towards Islam, and once people know the wisdom behind Islam, they get behind us. The fact that I was in first grade encouraged my community to learn about other beliefs as well. I am learning new things all the time about the Polynesian and Indigenous cultures.”

But the simple fact remains: there hasn’t been a practising Muslim playing rugby league at the top level in Australia since his retirement. What could be the reason behind the absence of players progressing? “I ask that question too,” says El Masri. “We need more Muslims out there. Times are changing as Muslim parents are becoming more dedicated towards their children’s sporting goals. Hopefully the next Muslim NRL player is on the way.”

As the 39-year-old points out, the Muslim community themselves have a duty: “To assimilate correctly, you must be honest, work hard and give respect, which would then allow us to remove misconceptions about Muslims. And working hard is more than applying yourself for two years, it is for a lifetime. For example, rather than complain about fasting and training, which I see some boys do, they must instead use this challenge to their advantage. And the higher the profile Muslims achieve, the better it is for everyone because it reminds Aussies that we also contribute to society. When that happens, everybody wins.”

The NRL has already set a precedent in prioritising pathways for certain communities. In its Reconciliation Action Plan, the NRL has pledged to increase the participation rate of Indigenous players from 12 percent to 15 percent at an elite level by 2017. It is a laudable ambition, of course, but astoundingly there is no comparable roadmap for Muslims, even though there are 476,300 Muslims in Australia, just short of the number of Indigenous Australians.

It doesn’t add up. And in some cases, the consequences can be disastrous.

Taha El Baf was a promising young league player, a 17-year-old with a deep passion for the NRL, and considered to have the potential to make a career out of the game. However his drive and energy was diverted by online radicals who recently lured the young teen overseas. Last November, the tall centre fled his home in Yagoona, in Sydney’s west, along with two of his brothers, to fight in Syria, much to the anguish of his parents.

Why would a footy-loving product of the public school system feel so detached that he would abscond to the dangers of Damascus? According to Taha’s older brother, Mouhamed, the issue involved discrimination. “Taha was a very good player for the Regents Park Pumas, but the problem was there was no one there to see him,” he says. “There’s no development in the area, because all the scouts go to areas with different cultures. In all our years there, not even one scout ever turned up! It doesn’t suit them to watch us. I guess they prefer to go watch players closer to the city from different backgrounds.”

Would more involvement from the NRL possibly have prevented his brother from fleeing overseas? “It could have been a totally different story,” Mouhamed says. “It might have made him feel attached, but despite his performances there were never any development officers watching. He really wanted to make the NRL as he was a big Bulldogs fan like the rest of the family. The fact is that he felt ignored.”

Brother Mouhamed points out that Taha’s frame of around 190cm and 90kg certainly ensured he had the physical requirements. “He had the size, great ball-handling and a strong step giving him many man-of-the-match awards. He wasn’t Benji Marshall, but with some kind of development his talent might not have been wasted.”

The rugby league adage of course goes that “if you’re good enough you’ll get there”. Wouldn’t traditional selection paths ensure the fairest approach? To that, the 30-year-old brother Mouhamed retorts: “Hazem El Masri was the last player to make it all those years ago, and there have been none since. Our community is a large one and there are heaps playing the game. Are you seriously telling me there are no talented Muslim boys? Not even one player? None? Is that logical? Tell me how that can be possible?”

In the competition between the major football codes for the allegiances of Australians, the AFL has a far better record for establishing elite pathways programs directed at multicultural players. The Bachar Houli Program, for instance, targets around 5000 players from Islamic schools across Australia. The very best players are identified, then given leadership courses as well as opportunities to train with Houli’s Richmond Tigers with a view to getting an AFL contract. This high-performance group will soon be expanded from 25 to 35 players. The program has received a $200,000 grant through the federal Attorney-General’s department.

Bachar Houli is one of just a handful of Muslims playing in the AFL; the Tigers midfielder is more than happy to put his name and energy behind the program. “We’ve had really positive feedback about the inclusiveness of our program,” he says. “There’s a place in our game for all cultures and backgrounds, and our program supports and encourages diversity in AFL and sport in general. The program has helped participants with their football abilities, but also reminds them to feel proud to be Muslim.

“I’m really proud and humbled with the encouragement and positive feedback I’ve received from all levels of the community about my program. It’s rewarding to know that this program, which has so much support from the AFL, the federal government, Australia Post and the Richmond Football Club, is making a positive difference to both the Muslim and broader Australian community. I’ve been fortunate to see it grow to a national level in a short amount of time.”

Besides the Houli program, the AFL also holds annual Ramadan dinners in Sydney and Melbourne allowing administrators to network and better connect with the Muslim community. Elsewhere in Sydney, the Greater Western Sydney Giants employ two Muslim community engagement officers.

One major obstacle preventing Muslims from attending football fixtures relates to the requirement for adherents to pray five times a day at specified times. Consequently, the AFL now insists all of its major venues provide prayer rooms, ensuring community engagement has the potential to develop to its fullest potential.

The AFL’s head office makes its stance on the issue clear: “Fundamental to the AFL’s diversity strategy, the Bachar Houli Program aims to strengthen leadership, promote values and provide unique football development opportunities for young Muslim men aspiring to play AFL football. The program uses sport as a vehicle for social cohesion and we are excited to see it grow in 2015, particularly in Western Sydney, the multicultural hub of Australia.”

Australia’s Muslim community has recently been at the centre of heated political debate regarding national security. Yet amid the mass media hype and the millions spent by Government on counter-terrorism measures, very little dialogue has centred on the role that sport can play in order to better connect with this sometimes disengaged group.

Events across the globe have resulted in Australia facing perhaps its greatest test of social harmony. Amongst this backdrop, an auspicious change has transpired; the Muslim community’s desire to build bridges and better connect with Australian sport has grown.

Dr Anne Azza Aly is an expert in the field of countering violent extremism. But the Associate Professor at Curtin University points out that sport, and in particular the NRL, has not done all it can to engage minority groups.

“Any organisation has a social responsibility to be inclusive,” Dr Azza Aly explains. “They have an obligation as a socially responsible organisation to look at gifted and talented pathways. Identifying and engaging the Muslim community through training camps and specific programs in Islamic schools is necessary, just as the AFL has done so successfully. If they were to be leaders and do that, the community will respond. Without outreach, nothing will change.”

Counter-terrorism is top of the government’s agenda, yet according to Dr Azza Aly: “There is a tangible benefit in preventing radicalism. These youths are being targeted and there is a need to engage them in the quintessential Aussie game. This would develop a bond and allow them to feel Australian.”

Muslim community leader Dr Jamal Rifi has attempted to foster that NRL-Muslim relationship. “I have spoken with Raelene Castle [Canterbury Bulldogs CEO] about involving the Bulldogs club in targeting the disaffected youth in the area,” says Dr Rifi. “We need another rugby league ambassador.”

For her part, Castle says her club is developing a new program explicitly targeting Muslims. “It’s something we are in the process of finalising. It’s twofold. It is to encourage young people to make good decisions. The second part is as a pathway into becoming high-performance athletes.”

Sydney’s south-west is rugby league’s heartland; more than 44,000 Muslims reside in the catchment assigned to the Canterbury Bulldogs. According to Castle, her contact with the community has been a great experience. “There are absolute positives about working with the Muslim community. While on one hand Muslims need to integrate, we also need to educate mainstream Australia. If we get Muslims playing league at the top level, they will become the norm.”

******

One shining example of success has been taking the field this winter in Sydney’s west. In 2011, Amna Karra Hassan decided to form the Auburn Tigers women’s AFL team, managing to attract a predominantly Muslim playing list, fusing the iconic AFL vest with the traditional Muslim hijab headscarf. Her initiative attracted the commercial sector, with Harvey Norman’s director, Katie Page, deciding to sponsor the women’s team.

An employee of the Australian Federal Police, Karra Hassan beams with pride as she speaks of her team. “I am a big dreamer – and dreams do come true. We now have the support to groom athletic girls.”

Around three-quarters of the club’s players are from Islamic background. Can having a team so concentrated with one religion be advantageous? Karra Hassan thinks so: “The conversations we have around religion, culture and contemporary news allows us to share our beliefs with mainstream Aussies and challenge each other’s stereotypes and assumptions. Regardless of background, questions are coming from curiosity, not bigotry or racism, and there is something very powerful in that. For women who haven’t interacted with Muslims, having just one positive experience is more powerful than any negative media exposure,” explains the 26-year-old.

Part of the advisory board for Multicultural NSW, Karra Hassan also believes Muslims might increase the value they place on sport. “In the past, a lot of our girls never engaged in sport. Education was their priority, as the migrant mentality is to earn money, whereas to broader Aussies sport is much more critical. So Muslims need to embrace that view, and over time it has progressed. Our Islamic beliefs and Aussie Rules football share the same values of fairness.”

In fact Islam has a deep-rooted connection and respect for sport; in one of Islam’s most important texts, The Hadith, swimming, archery and horse-riding are stated to be encouraged by the most esteemed figure in Islam, the Prophet Muhummad (peace be upon him). Such explicit references to sport debunk any theory of incompatibility. In fact, sport is one quintessentially Australian past-time that is in total harmony with Islamic doctrine.

But along with the successful participation of Muslims come the associated complications of managing religious sensitivities. The United States, for example, has had a long and proud history of elite Muslim athletes, most notably in the NFL and NBA. But when Kansas City Chiefs safety Husain Abdullah lay down face first after scoring a touchdown in 2014, he was penalised for violating the code’s celebration rules; in fact, Abdullah was re-enacting the Sajdah, a religious prayer – akin to a Christian’s raised eyes to the heavens in celebrations, or in the case of Tim Tebow, dropping to one knee and bowing his head before a game.

No doubt we have a way to go before our religious differences are celebrated rather than sanctioned. But sport is one way Australians can pick up the ball. And some sports are slow on the uptake ...

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open