With the NBA’s players and owners unable to agree on the division of money, the possibility of a lost 2011-12 season has become very real.

With the NBA’s players and owners unable to agree on the division of ‒ who would’ve guessed it ‒ money, the possibility of a lost 2011-12 season has become very real.

Photo by Getty Images

Photo by Getty Images

Another cultural artefact of the Great Recession: the planet’s best basketball players having to seriously contemplate spending a season in the prime of their careers in locales from Anatolia to the Antipodes. It makes you wonder what the legendary Michael Jordan, who did all his world-dominating from his base in Chicago, would think of this.

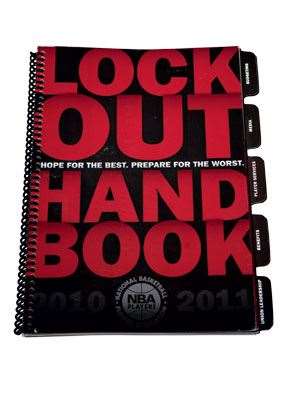

But we do know what MJ, who will be in Australia for the first time this month, thinks. He’s an owner of an NBA team and, accordingly, is arrayed on the side of management locking out the players and ‒ at time of writing ‒ likely endangering the 2011-12 NBA season that begins this month. Jordan offered his comments to an Australian newspaper in August, calling the league’s economic model “broken”, and received a US$100,000 fine for it (the NBA prohibits teams from making public comments on the labour dispute).

The crux of the clash is altogether common – it’s a battle over the division of money, but the dimensions of the disagreement are otherwise more complex. The players are good to go and play, and would readily accept the status quo in how they are paid. The team owners, however, have seen their chance to rearrange the NBA’s financial structure, which sees 57 percent of the league’s US$2.1 billion revenue go back to the players in salary.

Players and owners have not been able to bridge the divide over the dollars, and the nuclear option – loss of the season – has become very real. The league claims that two-thirds of its teams lost money last year, hit hard by downturn, and would stand to lose less money if no games are played than if they went ahead.

Jordan’s team, the Charlotte Bobcats, is a prime case of the battle lines drawn in this lockout. It’s a small-market club and can’t either generate the revenue or spend up to the level of a New York or Los Angeles. The NBA has a salary cap, but it’s “soft” – teams can exceed the cap through various mechanisms, but once they cross another payroll threshold, they pay a “luxury tax” back into a league-wide pool.

Throw in a maximum individual salary limit and it would seem more than enough to rein player payments in. The reality, though, has shown that the big clubs will spend their way into tax territory without a care, while the rest are chilled out of it, widening further the gap to the have-nots. In seeking the new division of revenue, the owners are also figuring ways to harden the cap, shorten player contracts and create greater profit certainty for each team.

It’s a reasonable case – a more level financial playing field to create a more competitive league, otherwise the game’s on the path to European soccer, which the NBA players will surely learn about during their various sojourns. The issue is, though, that the owners are trying to do it off the backs of the players, who rightly argue that teams are able to make money within the current structure – and what competitive business isn’t entitled to certain profits?

The players’ killer line is basically this – if badly overpaying players is what ails most teams, that’s the fault of the owners giving out bad contracts. Last year the NBA’s second-highest paid player, Rashard Lewis, was traded for its fifth-highest, Gilbert Arenas. Although, both made nary an impact on their teams and they were moved for each other because they couldn’t be moved for anyone else.

The owners, ultimately, are seeking protection from their own bad decision-making. Author Malcolm Gladwell wrote that these owners – billionaire successes in other fields of commerce – were somehow being defeated by the business of running a basketball team. His conclusion is that NBA teams aren’t businesses at all, but akin to a high-priced piece of art, a rare luxury good to be enjoyed for something other than monetary value.

The recently premiered film version of the book Moneyball, starring Brad Pitt, is a cinematic paean to the notion that sports teams have become smarter over the years and have all these sophisticated ways of making more informed decisions about how to put together winning teams. That, of course, is not Michael Jordan’s movie – his one had Bugs Bunny.

‒ Jeff Centenera

Related Articles

Jordan, Min Woo and fans helping Block avoid reality a little longer

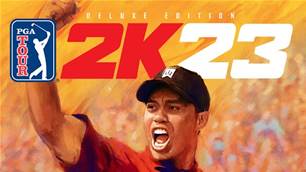

PGA TOUR 2K23 signals return of virtual Tiger Woods