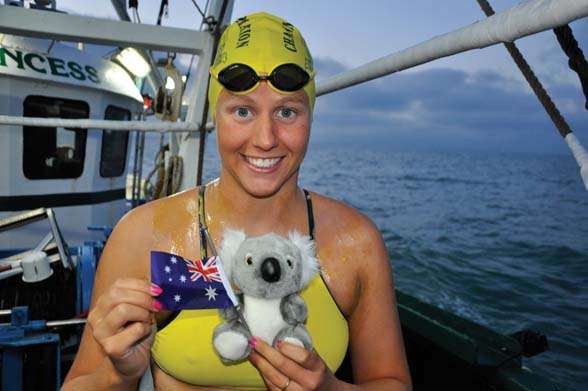

Chloe McCardel sets record for longest unassisted ocean swim.

In October last year, 30-year-old Melbournite Chloë McCardel swam from South Eleuthera Island to Nassau, in the Bahamas. If that sounds like something you do to kill time while you’re holidaying in the Caribbean Islands, think again. It was a new world record for the longest unassisted ocean swim in history: 124.4km. It took her 41 hours and 21 minutes. McCardel had been eyeing off that record because she thought it was actually quite gettable – it didn’t seem ridiculously far to her, especially when the water was warm there. She’s more usually found lapping the frigid waters of the English Channel; she was doing that two months ago, achieving what only three other swimmers in history have ever done: the triple crossing (that’s 34km per lap). It all places McCardel among this country’s greatest ever ultra-endurance athletes. This is a woman determined to rewrite all the record books – with that radiant smile on her face all the way. She told Graem Sims how to swim to hell and back.

BEGINNINGS

“I grew up in Balwyn, in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. When I was in primary school I did a variety of sports like tennis and gymnastics, but I only picked up swimming in grade six when the whole year level went to get swimming lessons. It was then that I realised that swimming was a skill – I couldn’t do anything more than doggie paddle. I was a bit embarrassed and so I asked my mum for lessons. I joined squad the next year and soon started competitive swimming. That soon got me to entry-level national age group standard, which wasn’t that high a level on the elite rankings, but it meant I was training with elite-level swimmers like [Olympian] Matt Welsh; he was in the squad above me and in some sessions we would do the same sets. So by Years Nine and Ten, I was swimming about seven squad sessions a week, doing three dryland weight sessions, plus a lot of different sports through school. I progressed quite quickly; I had a really good feel for the water and I loved that I could express myself when I was swimming – you’re using every muscle, so you really get a chance to be free. I loved that. There’s also a lot of structure, and I really responded to that, too. You’re learning all those swimming drills: you can focus on each individual drill and try to achieve things within each set or stroke that you’re perfecting. I just like all those little challenges.”

PUSHING IT

“I discovered I liked to push myself really hard. I wasn’t winning all the medals, but I got so much from the training, and that was enough. I was basically just going through pain levels – for some reason it really interested me. It was about punishing myself and seeing how hard I could go. Most people run away from pain, but I was like, ‘Bring it on – what can I do next?’ Unfortunately, in the squad I was in, you’re under the direction of your coach and they set the distance and the competition you’re allowed to enter – I was actually specialising in the 200m butterfly, which is a very punishing event. But we weren’t encouraged to do open-water swimming. So when I was 16 I retired in a way from competitive swimming – I was doing like ten sessions a week at that stage. Then when I entered university I did some elite-level triathlon, between the ages of 18 and 22. Again, I loved the fitness side of it, and I had this huge swimming ability, but my bike and run just never caught up with that. But that’s where I found I loved the open-water swimming.”

AMBITION

“I knew I wanted to be an elite level something. I didn’t really care at what. But I had a feeling that distance sport was going to be for me. So in 2006 I entered the Melbourne Marathon. And in 2007 I entered the Bloody Big Swim, which is a swimming marathon – it’s 11.2km. I decided to do both the run and the swim and then see which one works out better. The run was pretty good – I came 80th female. But the swim – I was first female and only one male was ahead of me. That gave me an indication of my ability. All those years going up and down the pool as a teenager, they hadn’t disappeared. That conditioning came back really quickly.”

AWE NATURAL

“I really had a love of the open water – it was sensory overload. It’s salt water, there’s no black line and you can really feel a link to the environment that you don’t get in these artificially created sporting environments. Marathon swimming is more wild like that. It was fun and it was hard. And I thought, ‘What next?’ I knew the pinnacle of marathon swimming was the English Channel, so I set a date for September 2009. I got back doing six or seven sessions a week, week in week out, feeling good, and then I thought maybe I should just go for a double crossing right from the get-go? So I trained up for that. And met my husband along the way. It’s a bit of a Channel love story: he was training up for his own single crossing and we met through a training session and we fell in love – little did we know we’d booked to swim it in the exact same week. He was very supportive, and we travelled over there together. So I did my single crossing, then turned around straight away and got back in, and I was swimming for another 14 hours and was about three-quarters of the way back, but unfortunately it wasn’t to be. The weather turned into force-4 and -5 conditions. Waves were going everywhere, the boat was losing me in the water, it was pitch black, and I’m getting hypothermic. I just had to get out of the water. But I did it the next year, in 2010.”

TRIPLE TREAT

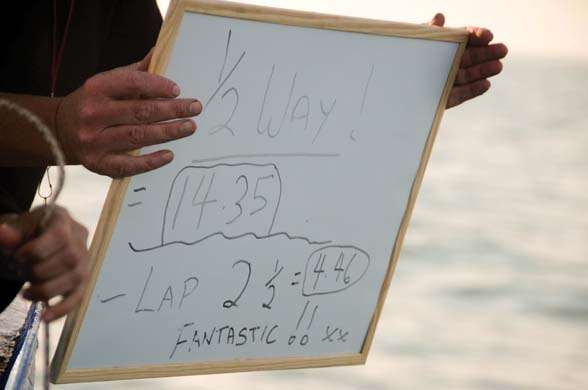

“I love incredible challenges, so after that I’m going, ‘Where’s next for me?’ I originally chose the English Channel because of its profile and its history and how difficult it is, so I decided to do a triple crossing in 2011, but it wasn’t until this year that I was able to complete it, because the difficulty is OFF the scale. They say a double crossing is eight times more difficult than a single crossing, and I would say doing a triple is 50 times harder than doing a single. There is absolutely no comparison. There’s only three people in history who have ever completed it. Four now! I was unsuccessful at the triple in 2011 and again in 2012. And I was over it by then – I needed a break from that intensity, because the training, especially the coldwater training, is really intense. So then in 2013 I tried to swim between Cuba and the USA, but I was foiled by venomous jellyfish. They nailed me. I felt like I was being burnt from the inside. Fireballs. I was paralysed – they had to drag me out of the water. That was horrific. But I wasn’t going to let that beat me. I decided to go back and find somewhere where there weren’t these crazy jellyfish and get the longest swim in history. It was set at 108km. I was like, ‘That’s a record I can get, I should go for that one.’ So last year I swam between two islands in the Bahamas. That ended up being 124.4km, and I got the world record – I was stoked with that. But it punished me. What it did to my body was horrific. That was 41 hours in the water – the longest unassisted ocean swim, meaning no shark cage or stinger suit or wetsuit, or snorkel or flippers. Once you start adding all these unofficial aids it’s not really that true anymore because they’re assisting tools; it just starts becoming another swimming event. I might use a shark cage in the future, but I don’t feel they really embody the true spirit of marathon swimming. A wetsuit gives you buoyancy and insulation – even a shark cage pushes you forward.”

THE ELEMENTS

“If a fisherman fell off the side of a boat in the English Channel, they would probably last just five to eight hours and then they’d die. And that’s in summer – not even winter. So anyone trying even a single crossing of the Channel needs to do a lot of cold-water training just so they can survive, and beyond that make forward progress. So physiologically, they’ve morphed into some half-cold/half-warm-blooded animal to be able to make it to the finish. Hypothermia will set in at different times for different people depending on how much training they’ve done, how healthy they are, and how exhausted they are, because you need energy to keep warm. If they’re not that fit, they’ve got no energy to keep them warm. Some people will get hypothermia within two or three hours of starting their swim. For me it started at night time at the end of the second lap, after around 20 hours. The air temp drops at night, and then the water temperature gets colder to reflect that, and you don’t have the sun hitting your back to provide warmth. Psychologically it’s tough when you lose the sun.”

DESIRE

“I have a strong desire – when I was a child I was very stubborn and no one could talk me out of anything if I had my heart set on it. So I’ve always been very focused and driven and for some reason marathon swimming allows me to take this stubbornness and mould it into something really special. The English Channel is such an incredible place. This is our Olympics. You don’t just give up because it’s too hard or too cold.”

FUEL FOR THOUGHT

“You have to be able to fuel yourself on these crossings. I have a combination of sports-specific energy gels – I use Gu. I have three Gus an hour and one of them is Roctane – it’s a style of Gu, customised for eight-ten-hour-plus marathon events. I find it gives me something extra – it reduces that perception of pain; I can push harder and not feel like I’m fatiguing. I don’t even try anything else anymore. I don’t need to trial a new nutrition system. I also have the equivalent of about one cup of caffeine every hour, contained in these gels. Surprisingly I don’t have much liquid – only about 200-300ml per hour. I’m immersed in very, very cold water so I’m not sweating. Because you get so cold during a big marathon swim I usually try to put weight on beforehand. That means I have to change my diet, so I go for a high-fat [good fat], high-carb diet. And I try to stick to the brown: brown flour, brown rice etc. I start trying to put on weight about three or four months out, which might sound a bit extreme, but by then I’m already training in cold water. To buffer that as much as possible I put weight on.”

DANGERS

“Even the word ‘jellyfish’ sounds so innocent – no one has nightmares about jellyfish. But these are like the little dark horses of scary marine creatures. If you swim into these things in northern Australia they are deadly. In Cuba there were box jellyfish: not quite as bad as ours but still extremely painful. Each time a tentacle hit me it felt like someone picked up a hot iron and stuck it into my arm. But in the Bahamas, about 20 minutes later the pain turned down about two levels, so for me that’s a good outcome for a Caribbean swim. I was being smashed by these things on my first night, but then I was really happy – I mean, I screamed a few times in pain, but then I realised, ‘Hey, this is liveable, I can keep swimming, so this is a good outcome.’ After that Bahamas swim I was hospitalised for five days because I had these huge welts over my body from sunburn that had all swollen up into large blisters. Your legs swell up and you can’t walk. That’s the most horrible swim I finished.”

HEY COACH

“I’m a coach now – I get to share my journey with so many others. I had 43 athletes swim the English Channel when I was over there this season. It’s pretty special when you’ve got these people on this high doing these amazing things. I’m now quite thoroughly addicted to the whole thing. You won’t be able to get rid of me!”

NEXT?

“No one’s done four crossings. That’s crazy. I’m not planning to do that. Next I’d love to do a big swim in Asia. I’d love to connect with people from that region, and I’m really curious. I would love to be able to bridge two points of land by swimming and bring in a whole community with me on another exciting journey.”

Chloë thanks her two sponsors: The Pool Enclosure Company (TPEC), and Lo-Chlor (AquaFresh and AquaSpa).

Related Articles

Training with the Cronulla Sharks' Michael Ennis

Training with the Cronulla Sharks' Michael Ennis