Aussie Moto3 maestro Jack Miller is preparing to shift gears up to MotoGP and out of the shadow of Casey Stoner.

In the space of five frantic minutes, Jack Miller had seized upon an opponent’s mistake to win his maiden world championship motorcycle race, embarked on a series of wild celebrations on his lap back to the pits, inadvertently dropped the F-bomb on live international TV and stepped onto a grand prix podium for the first time. And then his mask of bravado splintered.

Related:

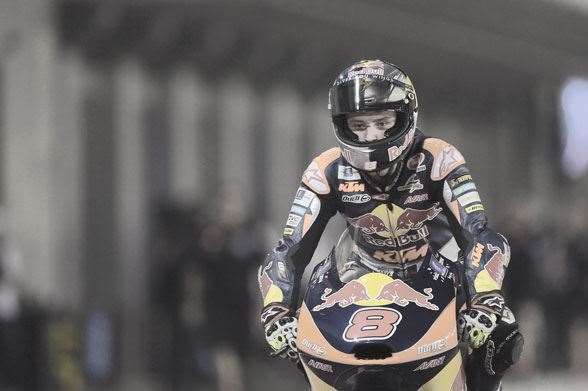

As the Australian national anthem rang out across the Losail Circuit in Qatar, Miller’s 100-watt smile dimmed, giving way to a quivering bottom lip. His eyes briefly met those of his parents Peter and Sonya in the throng below the victory rostrum, and he swallowed hard. The tears finally came, first in a trickle, then faster as he tried to blink them away. The crowd, and the other members of the MotoGP travelling roadshow, roared their approval for a victory that was as popular as it was unlikely.

This was a genuine feel-good story on a global scale; a gregarious Aussie teenager making good on an improbable journey from the outskirts of Townsville to take on – and beat – the best of the next generation of motorcycle racers from all over the world. That the victory came in MotoGP’s entry-level class, Moto3, and happened while most of Australia was asleep on an April morning at 4am mattered little. For when the book about Jack Miller is written, Qatar 2014 will surely be its first chapter – and it’s a story that many believe will end up with Miller’s name being placed alongside those of Gardner, Doohan and Stoner as Australians who conquered the world on two wheels at the highest level.

Success in MotoGP – the domain of Valentino Rossi, Jorge Lorenzo and new wunderkind Marc Marquez – is the long-term goal for the 19-year-old Miller, but compared to where he’s come from, it’s a goal that’s now very much in play. The improbability of a self-taught Australian dirt-track prodigy making his way to the world stage to take on the crack riders from such two-wheel hotbeds as Spain and Italy is one thing; to do it on the back of the passion, belief and financial outlay of a family from far-north Queensland is another entirely. It’s a tale that would be difficult to believe were it not true.

******

THERE'S NOTHING ABOUT the residence located just outside the edge of Townsville’s suburban sprawl that screams out that Peter and Sonya’s second child is the next big thing in international motorcycle racing from this country. A dirt road leads into a driveway, one part branching off to the family home alongside a waterhole, the other towards a giant blue shed, Peter’s workshop where he runs a business that makes drilling equipment for oil and mining companies. The only noise that interrupts the constant hum of cicadas comes at an occasional rush when fighter jets fly over from the nearby RAAF base. Jack Miller’s teenage bedroom sits seemingly untouched from when its former inhabitant last left it, framed photos of his early road-racing exploits on the walls, an old clothes hanger – stringing together slivers of bright ribbon adorning his sporting medals – protruding from the closet.

Peter Miller has a five o’clock shadow, a firm handshake and a salty vocabulary. Like his son, he talks as if there’s a time limit for his words to escape his mouth, racing through sentences, jumping from one topic to the next. A rare cause for pause comes when the flat-screen TV in the family lounge room runs an ad for the upcoming Moto3 race coverage, the voiceover describing Jack as “Australia’s great hope”. “It’s still pretty surreal to see the bugger on the TV,” he laughs.

Peter and Sonya made the move from New Zealand to Australia in search of a new life in the late 1980s. The couple’s first two kids were boys, Fergus preceding Jack, daughter Maggie coming later. When Fergus was five, Peter bought his son the motorbike he never had in his own childhood. But it was three-year-old Jack who was instantly hooked. “Jack just cried his arse off because I didn’t let him have a ride,” Peter remembers. “At some stage when me and Sonya were out, they conned one of the babysitters – ‘Oh yeah, Jack rides it all the time’ – and the next thing you know he was out riding it around the house as a four-year-old.”

One particular Christmas Day was an eye-opener for Peter. Jack was now five and had his own KTM 50 dirt bike to play with. “By the end of Christmas he had the bike with the bars nearly on the ground, power sliding this thing through corners – he just went faster and faster.”

Jack couldn’t say yes quickly enough when his dad asked him, aged six, if he wanted to start in junior motocross. In his first flat-track race meeting – the Queensland state dirt track titles, no less – Jack won his age group. “He always wanted to beat everyone in everything; he was an ultra-competitive kid,” Peter says. “There was his natural talent and no fear, but if there was a competition, he was right up for it. Add a competitive element to something and off he goes.”

The obvious progression was road racing, but with riders having to be 14 to compete on tarmac, Jack had to wait. With the lounge room TV cabinet starting to sag under the weight of dirt-track silverware, Peter entered Jack into the Motorcycle Road Race Development Association’s (MRRDA) 125cc category in 2009. The result? A championship win.

By the end of that year, Peter had what he describes now as a “you’ll never know until you try it” moment. Europe, the beating heart of motorcycle racing, was a world away. Was Jack really good enough to mix it with the best? There was one way to find out, a way that involved a giant leap of faith and no shortage of naivete.

“The business was going pretty well at that stage, and we thought we should try our luck in Europe,” Peter says, a matter-of-fact summation of a life-changing decision. “I built a trailer, packed the bike in it, put it in a shipping container and sent the whole lot off to Barcelona. Didn’t have a bloody clue how I was going to get it out of customs.”

The family bought an old motorhome, parked it alongside the beach at Castelldefels near Barcelona Airport and threw themselves headfirst into the Spanish CEV (Campeonato Espanol de Velocidad), the toughest 125cc domestic series in the world. “Jack’s riding and he’s coming 31st, 28th ... and people are wondering why we came all the way from Australia for that,” Peter says.

“We knew the old Honda we had was slow, but it didn’t matter. It was about learning for Jack, learning for us, being seen that we were serious and trying to do it the right way. Jack needed to learn race craft. It was about being on a slower bike and striving to be up there.”

The CEV’s wealthier outfits couldn’t help but be impressed by the family’s determination. One of the rider tutors employed by the category’s biggest team took a liking to Jack’s story, and would save the best tyres discarded by his front-running riders and give them to Peter on the quiet. They gleefully accepted unused fuel, scooped up whatever favours came their way and worked their backsides off.

By the end of 2010, Peter needed to be in two places at once. His business had, as he now puts it, “suffered without me being there to run it”. He wanted to stay, but the dream would be over unless the bottom line picked up. Peter reluctantly went back to Townsville, leaving Sonya and Jack in Europe for 2011. It was a packed year – Jack split time between the CEV, the German 125cc national title (which he won) and made a handful of world championship 125cc appearances, but it was a year that led to a gig in the entry-level MotoGP series rebadged as Moto3 for 2012. Eleven years after he’d first competed in motocross, Jack Miller had a full-time grand prix ride. Now, then, for the hard part: keeping it.

******

CASEY STONER ALWAYS DID things his way, which was to turn up in the MotoGP paddocks of the world, ride the wheels off whatever bike he was given, show little interest in any other part of the business that is international world-class motorsport, and retire at the age of 27 with a CV that contained a pair of world championships that you always felt would have – should have – been more had his career run its natural course. His disdain for every other aspect of the sport besides riding has been well-documented, including in this very magazine in November 2012. In the first race after Stoner’s departure at Qatar in 2013, Autosport columnist Toby Moody described the “lifting of the Stoner fog” from a sport that missed his riding brilliance, if not his prickly personality.

Stoner’s absence from MotoGP has been keenly felt by the sport’s broadcasters and event promoters in Australia, with Channel Ten offloading all but the premier-class races to pay TV this year, and crowds at Phillip Island last season well down on 2012 for Stoner’s swansong. Stoner’s departure created the opportunity for another local to step into the spotlight, and Jack Miller – whose career in the junior international category out-ranks Stoner’s – is on the right path.

Miller’s personality is the polar opposite of his compatriot. He’s loud, gregarious, confident but entirely likeable, and there’s a certain wide-eyed enthusiasm to everything he does that’s infectious. He arrives in the paddock for “work” early, stays late, talks to everyone, zaps around on a scooter and hangs around with his mates. At the end of a day of practice, qualifying or media work at a grand prix, while the other riders head off into the evening, Miller can be found out running the track, burning off energy, visualising lines to take, seeing what he can discover about the circuit at slow speed. Describing him as a fidget is kind. “It’s the only time you get to hang out with people who speak English, so you’ve got to make the most of it while you’re there,” he reasons.

“It’s where I feel at home, especially in Europe. The energy works for me and it’s the place to be so I can get into the right brain space.

“It’s no fun if you’re not with friends, and I don’t see the point of being here if you’re not having fun. Then it becomes too much like work. It’s a serious job, but it’s a fun job as well.”

******

ON A WARM FRENCH SUMMER'S day in May this year, Jack Miller was on top of the world. The Moto3 race at Le Mans had been a breathless bare-knuckle stoush between a dozen riders, places changing corner by corner for seemingly all 24 laps. It was the type of no-holds-barred race where reputations can be made, where bones can be broken, where egos can be irreparably bruised.

Miller came into the fifth round of the season off the back of that breakthrough win in Qatar and a subsequent success in the next round at Austin in the United States, but both of those rides were a Sunday stroll in comparison to Le Mans. From second on the grid, Miller found himself as low as seventh as the laps ticked down. It was a situation that called for something special. Miller sharpened his elbows, muscled his way towards the front, made a daring dive on the brakes past the Honda of Spanish rider Efren Vazquez on the last lap and held on to win by nine one-hundredths of a second. The top nine finishers were separated by one-and-a-half seconds – as long as it took you to read the first five words of this sentence. Even by Moto3 standards, where grids of 35 mostly teenage riders fight like their lives depend on the result, this was a race for the ages. It elicited a Miller celebration from the top shelf, the ecstatic Aussie climbing up the trackside fence to throw the bulk of his riding kit into the crowd before some impromptu breakdancing in a nearby gravel trap. His post-race debrief after retaining his championship lead contained less profanity than his Qatar reaction, but was just as memorable.

“In other races I was too much of a pussy in the fight with these guys,” he said.

“There’s fingernails, there’s hair-pulling, everything goes. Today was just an all-out brawl and I was lucky enough to come out on top and actually stay on the bike.”

In the post-race euphoria, it was easy to forget that the Le Mans win, and the ones that preceded it, don’t happen but for one wet Sunday in Germany in 2012 and the sequence of events that followed. In his first full season for the lowly Caretta Technology Team, Miller had finished just two of the year’s first seven races, as the realities of competing in the world championship bit hard. “I basically felt like I’d been kicked in the nuts over and over,” he remembers. “You walk away really sore and you think ‘fuck, is this really what I want to be doing?’ because the results were no good.”

But then came the race at the Sachsenring – a track he knew from his days on the German domestic scene – and a summer’s weekend when the heavens opened and soaked the undulating circuit just outside of Chemnitz. In conditions that are often the great leveller for underpowered and underfunded bikes being ridden by promising new talent, Miller finished a remarkable fourth. In a season where he could manage no better than 13th in any other race, it was an outlier of a result, but one that was noticed by someone who mattered.

Emilio Alzamora won the 1999 125cc world championship for Honda with an approach based on stealth; he remains the only rider in world championship history to win a title without a single race victory in a season. After his retirement in 2003, Alzamora developed into a key player behind the scenes with the Monlau operation in Spain, becoming a mentor to an up-and-coming talent by the name of Marc Marquez and running the Estrella Galicia team in the entry-level Moto3 class. Alzamora had seen what Miller could do through the Spanish domestic series, and knew results like Miller’s in Germany could only be achieved by a rider with immense, if untapped, talent.

Peter Miller attended just one overseas race in 2012, in Japan, and it was at Motegi that he had a conversation which proved to be a watershed moment in his son’s career. “Emilio said Monlau and the Estrella Galicia team would like Jack to ride for them, but that I would need to pay for it, and that they wanted him to drop back to the Spanish championship until a ride opened up in grand prix,” Peter says.

“They’re one of the best teams going round, but we’d come too far, so I said no. I was humbled that he wanted us, but at the same time I was miffed that he wanted us to step back to the Spanish championship, because I thought Jack had earned his stripes.”

Peter sniffed around for other options for Jack, but the end appeared nigh. “Our money was done by then,” Peter remembers. “That was it. The mining game back at home was crap, and things were running down.”

The Millers’ saviour came from a most unlikely source. At that year’s Australian grand prix at Phillip Island – a sun-soaked celebration for Stoner as he won his sixth-straight home GP before his retirement – Miller endured a disastrous Moto3 race, getting penalised for jumping the start and finishing a despondent 21st. But away from the record crowds that descended on the Island that weekend, Miller’s future took an unexpected twist.

Peter met with Mike Trimby, the secretary of IRTA, the International Road Racing Teams Association, and Javier Alonso, managing director of Dorna, MotoGP’s series promoter. Stoner was on the way out, Australia was a key market for the championship with a history of riders stretching back to its beginnings in 1949, and, well ... did Peter need some financial help to keep Jack in Moto3 for 2013? It was a conversation Peter could barely believe he was having.

“Dorna wanted to have an Australian up there, and they said Jack was seen as being the next big prospect, so it was in their interest to help keep him in the game,” Peter says.

“To get some help from Dorna after everything we’d been through was pretty special.”

After finishing 23rd overall in 2012, Miller moved to the Racing Team Germany set-up, riding a Honda for the team run by ex-racer Dirk Heidolf. Invigorated by his career coming off life support, it was a breakout campaign on machinery that didn’t have the grunt to match the all-conquering KTM machines at the front of the field. All of that race craft honed from scratching around towards the back when he first came to Europe started to pay dividends. KTM riders won all 17 races, but Miller managed to overcome a noticeable speed deficit on the straights by being a demon on the brakes, and rode smarter than he’d ever ridden before. By the end of the season, he’d finished fifth in two grands prix and was a heady seventh in the standings, the second-best rider not on a KTM.

Miller’s increasing maturity wasn’t solely restricted to when he was on track. Finishing hot on the heels of the best bikes in the category week after week was satisfying, but he wanted more.

The Red Bull-backed KTM outfit, run by former Finnish racer Aki Ajo, has been the team to be with in the smallest world championship class in recent years; Marquez won the title riding for Ajo’s team in 2010. Miller wanted in. “I went to Aki and said, ‘I want to ride for you,’” he says.

“I had bigger offers on the table but I wanted the one that I liked, a team that had the results. Sometimes you’ve got to go with the heart. There’s not much money to be made in Moto3 anyway. It’s really just enough to keep me going and put some food on the table. MotoGP’s where the money’s made, so you’re better off having a decent team now than a bigger wallet and a shit bike.”

Once the deal was done, Jack fessed up. “As soon as Aki said ‘yes’, Jack then told me what he’d been up to,” Peter grins.

“That’s ballsy, but I’m not that surprised. Jack’s pretty good at taking control of his own destiny.”

******

TWO YEARS AFTER a meeting at the Australian grand prix changed Miller’s career, the 19-year-old returns to Phillip Island this October as a genuine world championship chance. But regardless of whether he wins the Moto3 championship or not, Miller is moving on – and moving up – in 2015.

When the world’s premier two-wheel championship reconvened after its mid-season break at Indianapolis in August, Miller’s name was the talk of the paddock. A move straight from Moto3 (where the bikes weigh 80kg and produce just 56 horsepower, straight to MotoGP, where the 160kg, 1000cc million-dollar brutes pump out 230-plus horsepower and nudge 350km/h) was being discussed as a risky, but realistic proposition. As media followed Miller up and down the vast Indianapolis paddock and Repsol Honda team principal Livio Suppo went from one closed-door meeting to another with Honda’s other teams, the likelihood of Miller becoming the first rider to jump from the sport’s smallest class to its biggest since fellow Aussie Garry McCoy in 1998 became increasingly likely. And some of MotoGP’s biggest names were quick to offer their endorsement of his talents, turning the pre-event press conference – much to the chagrin of the local media – into a Miller love-in.

American Nicky Hayden, the 2006 world champion, believes a MotoGP bike could really show what Miller is made of. “I think his talent will only come out more on a bigger bike where he has more power and can maybe get away with more, maybe like Marc [Marquez] does and like Casey [Stoner] did,” Hayden said.

“He’s wild a little bit, but normally on the track he doesn’t make many mistakes, so he’s got a really bright future if he stays healthy and keeps everything together.”

Ducati’s Cal Crutchlow also invoked the name of Australia’s most recent MotoGP star when discussing the rider many believe will be our next. “He’s absolutely a special talent,” the Briton said. “Hopefully soon he can start to come up and show us his true talent on a bigger bike. People are already comparing him to Casey. He’s going to be there, and he’s going to be a fast guy at the front of MotoGP in years to come.” High praise indeed.

Australia has a rich history in the premier class of two-wheeled motorsport, with an Australian rider featuring on the grid for the past 31 years. But while the likes of Bryan Staring and Broc Parkes have merely made up the numbers on uncompetitive machinery for the last two years, Miller is our next chance to be a genuine world-beater, a realistic candidate to fill the gaping hole left by Stoner. The fire he first showed as a five-year-old that Christmas Day, his dirt bike sideways, his knuckles inches from the ground, burns as fiercely as ever. “Being at the front is what I expect from myself and it’s what I’ve been working towards for the last three years; what I’ve been trying to do,” he says.

“I put more pressure on myself to do well than any pressure I get from the outside – it’s always going to be like that. I’m happy if people want to have big expectations for me, but I haven’t really done anything yet.

“But it is pretty cool to be in that conversation. If I can be close to any of those other guys before me, I’d be happy.”

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)