It's not just his runs and wickets we'll be relying on at the 2015 World Cup.

Dateline: ’Gabba, January last year. England, losers of all five Ashes Tests that summer, has also dropped the first game of the ODI series. At last, the Poms’ fortunes have turned in Brisbane, where they’ve posted 300 batting first, only the eighth time the Australians have conceded trips in a home ODI. The Englishmen have made their total efficiently, in the modern fashion: 50 off a little under ten overs, 150 just into the 33rd over. They’re on 178 when Eoin Morgan is joined by Jos Buttler at the fall of the fifth wicket, 77 balls remaining. The pair, perhaps the two best “finishers” England has, pilots the side to its impressive total, not far off the 316 runs combined it scored in two innings in the ’Gabba Test.

“They got away from us,” says James Faulkner, with a knowing edge. He bore the brunt of Morgan’s closing flourish, clubbed for three sixes by the Dubliner and conceding 35 from his last three overs. Faulkner finally gets him in the 50th over, but Morgan’s 106 has set England up. The Aussie chase stays ahead of the required marks, but the wickets are falling with greater regularity. By the 35th over, it’s seven down, 206 on the board, with Faulkner called to the crease.

“Momentum was back their way,” he says. “I remember Nathan Coulter-Nile got put in ahead of me because of the power play. They wanted me to go in after him, for a bit more structure.” Coulter-Nile and then Mitchell Johnson are dismissed, leaving Faulkner with Clint McKay for a solitary partner, and the daunting equation of 57 off 36. Faulkner understands that it’s on him to get most of the runs, which he decisively resolves by hitting consecutive sixes off Ben Stokes, then taking a single to expose McKay. “It’s about getting the right balance,” says Faulkner of the finisher’s method. “Sometimes, if you face a couple of dots, you tend to choke up a little bit and think you need a big shot. But a lot of the time, it’s better just to get off strike.

“For me, it was about picking who I was going to try and take down, who I was going to score my runs off. There was a little bit shorter boundary to one side, where the players’ boxes were. Anything in my area I went after pretty hard, and from the other end, it was about rotating the strike, get six or seven an over.”

Facing Stokes again two overs later, 37 needed off 20, Faulkner lifts one high to the midwicket boundary, where Joe Root almost pulls off a one-handed all-timer, but can't avoid running over the rope. With that heart-in-throat moment averted, the elusive momentum had seemingly turned. On 44, Faulkner hits one into the mezzanine level and gives the briefest of half-century salutes. There’s still 19 to get off nine, after all. The very next ball is in the top tier, and the ’Gabba is vibrating.

The cold, calculating practice of closing out cricket matches becomes performance art in these moments, feeding off the energy of the crowd. “When you’re playing at home, there’s more adrenaline; you feel like you’ve got some support,” Faulkner enthuses. Do you get a chance to soak it in? “I think you have to. You have to ride the wave with everyone else at the ground. There’s so much emotion when you’re getting close, and that’s when you’ve got to make it happen.”

Last over, 12 off six, Tim Bresnan to bowl. The first delivery is a pretty good slower ball, which Faulkner edges behind. It carries right over the keeper’s head for four. The English players can sense what’s coming. Faulkner thumps the next one through the onside gap for four. In the commentary box, another guy who was pretty good at finishing games for Australia, Mike Hussey, is moved to remark: “He is not panicked at all ... even when Australia was nine down.” The wave finally brings Faulkner in when he beats cover for the winning boundary. Game: closed.

Of Faulkner’s match-winning 69 not out, 55 of those runs came in the last-wicket stand. While the big hits left their mark, he’d also taken 21 singles. He’d pulled off an absolute heist, and left England wondering what they had to do just to win a game. The result was a shock, but not where it came from. Within Australian cricket circles, Faulkner had already established a reputation as a guy you want out there at the end of a match. The Tasmanian, who, with George Bailey, was one of two Aussies named in the ICC’s World One-Day XI for 2014, has that wonderful attribute for an all-rounder beyond ability with both bat and ball – action seems to follow him around. As chairman of selectors John Inverarity noted in naming Faulkner in the 2013 Ashes squad, he was a “cricketer who gets things done”.

This all-action quality serves Faulkner very well when the game reaches its most climactic, pressure-filled stage. “I come in at the end of every innings, and I train for that sort of scenario: the 30 off 20, the 40 off 25 that you need at the end to make a big total to defend, or in a chase. That’s my job,” he says. And when preparation meets opportunity, as the proverb goes, improbabilities like what occurred at the ’Gabba can happen. “Everything aligned at the right time. You’ve got to have a little bit of luck as well as skill, in that sort of situation, to come off.”

THE RETURN OF CRICKET'S WORLD CUP to our shores after a 23-year interim – roughly the lifespan of the 24-year-old James Faulkner – underscores how the nature of the limited-overs game has changed. In its first two decades, 50-over cricket hewed to a logic influenced by the older form of the game: start deliberately, build up wickets in hand and hit out in the last ten overs, with a strong total in the area up to 250 runs.

Perhaps because the Cup pulls together the disparate elements of the cricketing planet, the event has historically been something of a seedbed for innovation in the game. In 1992, the New Zealanders fully adopted the then-novel ploy of pinch hitters at the top of the order, with Mark Greatbatch becoming the symbol for the Kiwis’ surprise success. The idea had been circulating since the late 1980s. A 1988 paper by Swinburne University mathematician Stephen Clarke recommended that teams try to score faster from the outset – in a statistical sense, a dot ball late in the innings was no worse in value than a dot ball early in the dig. As Clarke put it, the prevailing logic of ODI was akin to a runner walking in the early part of a race to preserve energy for a sprint at the end. It didn’t make sense to conserve wickets at the expense of run rate; the maths suggested that a team try to score faster early on than its expected rate over the entire innings.

Theory is rarely validated so neatly as this one. At the next World Cup, on the sub-continent in 1996, Sri Lanka stormed to victory on the back of cavalier spirit. Its soon-to-be-famed opening pair of Sanath Jayasuriya and Romesh Kaluwitharana attacked the first 15 overs, when the field was in, in a manner usually reserved for the last ten overs. While Australia was still opening with Mark Taylor (career ODI strike rate: 59.46), Sri Lanka’s flying starts made a huge psychological impact, as well as being statistically sound. Curiously, their impact looms larger in the memory – Jayasuriya was named player of the Cup, but he was only 17th in the tournament in runs scored. He had faced 168 balls total in six matches, and with Kalu, had only two opening stands of more than 50. In the final against the Aussies, neither reached double figures; instead, it was some classic middle-order play from Aravinda de Silva that delivered the Cup.

But after ’96, there was a great inversion in the one-day game – every big bopper and elegant stroke-player could now be found in the top three of the order. The Aussies, heeding the lessons of their loss, would replace Taylor with Adam Gilchrist, a rather definite statement of going in a different direction. But while the focus was on the start of the innings, the new line-up construction in ODIs had a side effect: it created the space in the middle order for the type of batsman who would evolve into the role of finisher.

For Australia, the archetype of this specialist had been in the XI in the ’96 Cup final. Michael Bevan had made his name in the area of late-game heroics earlier that year, when in a New Year’s Day match against the West Indies at the SCG, his scrambling 78 not out had salvaged his team’s innings, then he struck the winning boundary from the last ball of the match. In the following years, Bevan became a cornerstone of the one-day side at number six, his specialisation becoming ever more pronounced as his Test career never achieved the same lift-off. The record was unmistakable, though – Bevan earned widespread acclaim as the world’s best one-day batsman, and still owns the highest career average in the form among the major cricket nations, thanks largely to the fact that a third of his 196 innings ended up not-out. More than that, it was his method that intrigued. Unlike the last-ten belters of old, Bevan was crafty, working the ball into gaps and using his superior speed between wickets to find extra runs and apply pressure to harried fieldsmen.

So while every team had re-cast its top order ahead of the 1999 World Cup in England, the tournament came down to some high-level exercises in finishing. Australia’s two encounters against South Africa went down in lore, with Steve Waugh and Shane Warne authoring some of the finest moments of their grand careers. But the two teams were also geared for the final overs – where Australia had the cool-handed Bevan, the Proteas were riding Lance Klusener, a classic late-game mauler. The South African all-rounder had scared people in ’99 the way that Jayasuriya had done three years earlier, and was similarly honoured, as Klusener was named player of the tournament. In the Edgbaston semi, Bevan had come in at the 17th over and lasted until the tenth wicket, posting 65. In the South African chase, Klusener had come in with 39 needed off 31 balls, and went about getting it. Needing nine off the final over, with only one wicket in hand, Klusener hit boundaries off the first two balls, but then partner Allan Donald was run out in an epic mix-up. The tied result sent the Australians through. The one-sided final against Pakistan needed no great finishing.

Bevan played in another World Cup winner, in 2003, before his ODI retirement, and he’s been followed since in the role by the capable likes of Hussey and Bailey. Faulkner is the presumptive heir in this line, although there are options in Australia’s deep 50-over deck ahead of the World Cup – Steve Smith, for one, has the kind of inventive stroke play and energetic mien in the middle to be an ideal player to hold the fort. But after watching Faulkner seal the November one-day series against South Africa with 34 off 19 at the MCG, Smith made it known who had claim on the spot. “We call him ‘Bevo’ in the sheds,” Smith told a Sydney newspaper. “He comes in from ball one and looks like he’s been out here for about an hour.”

James Faulkner has another interesting characteristic as a closer – he does it with both bat and ball, often tossed the rock in the last few overs to try and stop the opposition doing what Faulkner does to them with the bat. It’s definitely a tougher deal; there’s been a run-scoring explosion in one-day cricket, driven by an increase in boundary hitting from better-armed, less-inhibited batsmen. Few teams will blink at a target of 250 at this World Cup.

In Faulkner’s view, it’s about managing momentum. “If you get off to a flyer, you’ve got to make sure you capitalise. That’s how you get big totals. And likewise with the ball; if you get early wickets, you’ve got to make sure you maintain the pressure. There’s no point getting early wickets and you’re still going for seven or eight an over. If they form a partnership, it can easily swing back to their favour.

“For us, we have a massive focus on taking wickets. If you continue to take wickets, that’s the way to really break the game open. I know that’s stating the obvious – instead of restricting at the end, we’re looking to take wickets, because we feel that’s the main way to stop teams getting over 300 ... you still try to bowl for dots, but at the same time, every now and again, you’ve got to be ballsy enough to be able to throw a ball out there to take a wicket. We see a lot of teams stall toward the end purely because of wickets.”

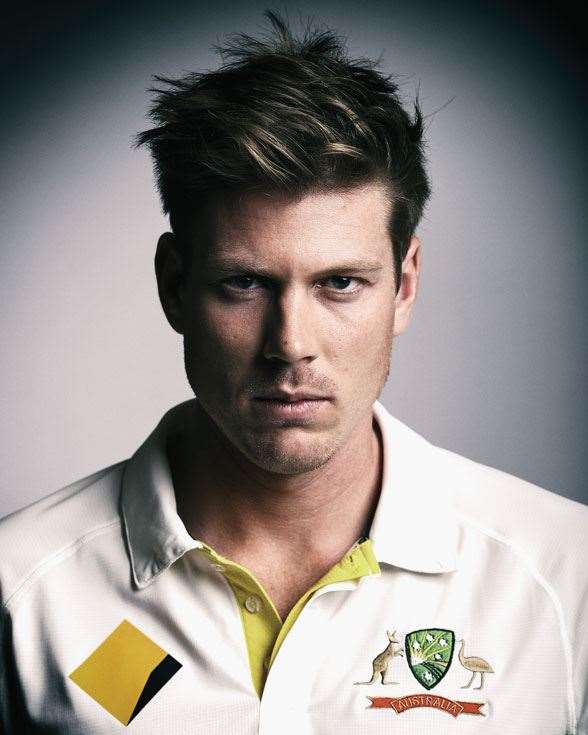

Faulkner and Clint McKay needed 57 off 36 against the Poms at the 'Gabba last summer. Job done. (Photo by Getty Images)

Faulkner and Clint McKay needed 57 off 36 against the Poms at the 'Gabba last summer. Job done. (Photo by Getty Images)Faulkner was involved in the epic series in India at the end of 2013 that encapsulated the nature of contemporary one-day cricket. The five completed games stood out for the near-surreal number of runs scored, even by the standards of the sub-continent’s amenable pitches and short boundaries – only once was there a total less than 300, and those gaudy figures were successfully chased three times. The third match, in Mohali, was where Faulkner first flashed his finishing kick for his country. He had been savaged by MS Dhoni at the end of the Indian innings, conceding 32 runs while bowling the 48th and 50th overs (he had given up 33 in his previous eight). In the Australian innings, Faulkner came in with his team still 91 runs short of the target 304. They were still 44 runs away with 18 balls left, when Faulkner went nuts, hitting four sixes in one Ishant Sharma over. For good measure, Faulkner ended the game, with six runs required, with another one over the rope. He had made 62 off 29 balls.

In the deciding game of the series in Bangalore, Rohit Sharma, owner of the ODI-record 264, hit his other one-day double ton. Set a beyond-daunting 384, the Aussies slumped to 4/74. It looked surely lost, but part of the closer’s creed is to believe that no total is beyond reach. “By the end, we were a chance,” Faulkner says, after Glenn Maxwell and Shane Watson, both facing 22 deliveries, made 60 and 49 respectively. But it was Faulkner who dragged the game back into the balance, striking the fastest ODI century ever by an Australian, off 57 balls. At the end with Clint McKay, in a bit of foreshadowing, the pair added 115. The chase, however, fell 58 runs short. “We just kept losing wickets throughout. It was the only thing that was stopping us. I have no doubt if Watson or Maxwell were there a little bit longer, and someone was there to hang around with me, the three of us were going really well. We were a fair chance of getting it, and I could tell by looking at the Indian players’ eyes. They thought we were a chance as well.”

It’s another – and perhaps the key – tenet of the closer’s mindset: you win some, you lose some. Being there at the decisive moment means having to live with the random nature of results, something that certain personality types are better equipped to handle. A big part of Faulkner’s make-up is his competitive spirit and pugnacious carriage, which led to at least one notable on-field exchange with West Indies’ star Chris Gayle. Faulkner admits that a healthy dose of confidence is almost an occupational necessity. “You’ve got to be bulletproof, but you’ve also got to think about how you’re going to do it,” he says. “There’s no point saying, ‘I’m going to go do it.’ That’s probably the hardest thing. You have to figure out a strategy and back yourself to do it; there’s no point just swinging every now and then.

“I’ve said it heaps of times: it’s alright to be getting praise when you’re doing well, but at the same time, there’s been lots of times when I’ve stuffed it up. And it’s a shocking feeling when you let your team down at the end of an innings.

“You have to learn from that, and I suppose some people don’t come back from it. It’s a matter of trying to improve and sort it out as quick as you can, and when it does happen, it might only happen two out of ten times rather than six out of ten times. And purely that’s a confidence thing.”

And from their own confidence, cricket’s best closers will be counted upon to steady their teams’ nerves during World Cup crunch time. If Bevan was acknowledged as the first of the master finishers, the mantle has since passed to MS Dhoni. The Indian captain has a similar capacity for keeping the endgame equation in his head, and adjusting how he bats accordingly. After the last World Cup, Dhoni owns the most prized trophy a finisher could have – he hit the clinching runs in the 2011 final.

Similarly, England has a wicket-keeper-batsman to see it through to the end in Jos Buttler. The 24-year-old was acclaimed earlier this year by no less a figure than Viv Richards for his finishing skills, a quick-fire scorer with all the shots. By contrast, those free-swinging Sri Lankans have cultivated a technical classicist in Lahiru Thirimanne to be a steadying hand at no.6 behind the likes of Sangakkara and Dilshan. And while big-hitting David Miller is the recognised finisher for South Africa, it’s a previous holder of the role that will have the Proteas’ opponents worried if they see him at the end. Even Faulkner concurs: “The best by far is AB de Villiers. He’s phenomenal. He’s the one that really stands out.

“The way he scores all around the wicket, the way he controls the innings, he has a huge presence on the ground. He’s so disruptive, he can hit any bowler; no matter if they’re going 150km/h or if they’re an off-spinner, he’ll hit them wherever he wants to.” De Villiers is a prime case of a player almost overqualified to be just a finisher – as great a batsman as he is, it’s no surprise that he’ll excel at whichever point of the innings he comes in. That’s also the case, on the bowling side, for his team-mate Dale Steyn, who has become just as formidable bowling the final overs as the opening ones.

But bowling at the “death” has also proven to be a place for the idiosyncratic. Ian Harvey carved out a one-day niche as a late-overs specialist, with his dot-inducing repertoire of slower balls. As T20 has also shown, awkward spinners such as the West Indies’ Sunil Narine are very effective in disrupting the rhythm of batsmen looking to make every delivery pay off. In the realms of awkwardness, few bowlers can match Lasith Malinga, who Sri Lanka is hoping makes an on-schedule return from injury for the World Cup. “When he’s fit and firing, with his action and everything, he’s so hard to get a hold of,” Faulkner says of his Big Bash League team-mate. “He’s got a different action, if you haven’t seen it as much as other blokes, it’s so unique. All of sudden the ball’s past you. He’s got a different skill and he’s very good at it.”

The skills of these fast-finishing stars will be stress-tested when the cricket world gathers here in February and March. To paraphrase the line from Glengarry Glen Ross, the Cup is for closers.

By Jeff Centenera

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)