Late hits on Cowboys and Maroons legend a mark of respect ... sort of.

The best method of stopping a player of Johnathan Thurston’s class is to wait until he has passed or kicked, then charge at his ribcage when he’s off-balance (or tracking the trajectory of the ball with his eyes). If you hit him hard enough, or order one of your bookend forwards to do the dirty work, you won’t injure him permanently, but you just may send him to the showers early, rendering him useless against your one-dimensional game plan. There’s that method, or there’s another one, which is all about trying to actually outplay him in the spirit of sportsmanship. You can purchase coaching manuals on this method from your local bookstore. Just head to the fiction section; it should be sitting there waiting for you next to works like Wuthering Heights and The Great Gatsby.

No rugby league pre-game team talk has ever focussed on physically targeting the opposition’s lesser-known players, besides blokes on debut. Whether ordered to before the match by their coach, or as a collective in the heat of the battle, the Newcastle Knights handed the North Queensland Cowboys’ 200-plus gamer plenty of attention off the ball and in the ruck during their round two clash in Townsville this year. When Knights enforcer Beau Scott aggressively launched himself at Thurston seconds after he’d passed, the phone lines, social media and sports journos erupted, taking a side in the latest round of the “it’s a man’s game vs player welfare” debate.

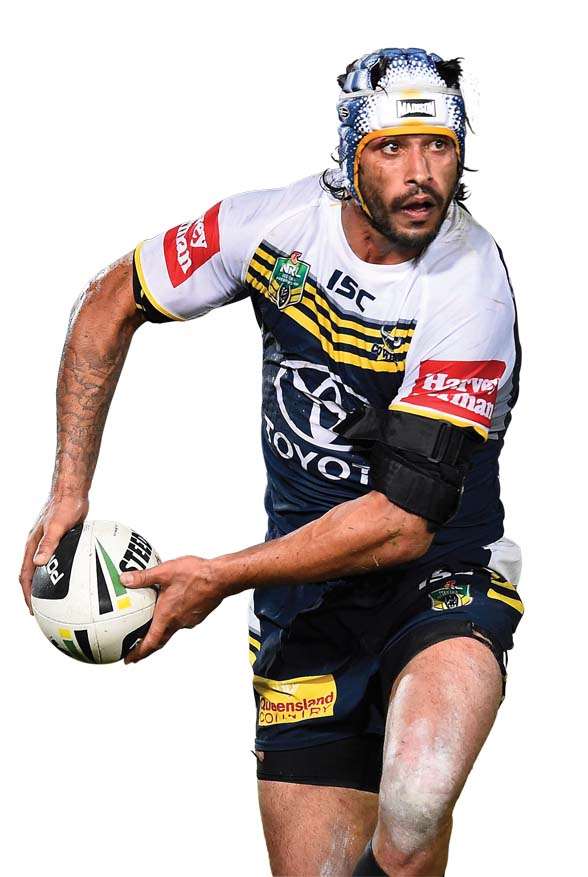

In another tackle during the same match, the 179cm-tall, 85kg Thurston was flipped over onto his head. He even finished the game with a black eye for good measure. In the days following it was argued by some that this kind of treatment has been a part of rugby league since, well ... forever, and that the only reason the issue was back in the news was because Thurston was the victim. Others argued that it’s because this kind of brutality is carried out on the game’s biggest stars that parents are increasingly steering their children away from playing rugby league and pointing them towards soccer or Aussie rules instead. A press snapshot of Thurston’s busted eye at full-time went viral, providing handy evidence for their cause.

Melbourne Storm skipper Cameron Smith, a long-time team-mate of Thurston’s in Queensland and Australian representative sides, argued that tougher action needs to be taken on players who target playmakers with late hits. Smith argued that no one would want to see a shyer, more timid version of Thurston in attack, let alone one sitting on the sidelines with cracked ribs.

It went on. In the days leading up to the Cowboys’ away game against the Brisbane Broncos the following week, Thurston quipped that it was now “open slather” on playmakers after Scott escaped suspension. Broncos coach Wayne Bennett fired back, claiming that the “drama queens are out of the cage”. Bennett argued that halves have been copping treatment like that dished out to Thurston for years, and that JT was considered no different to any other number six or seven in the NRL. (It wasn’t missed by many that Bennett coached Scott during his time at the Knights.)

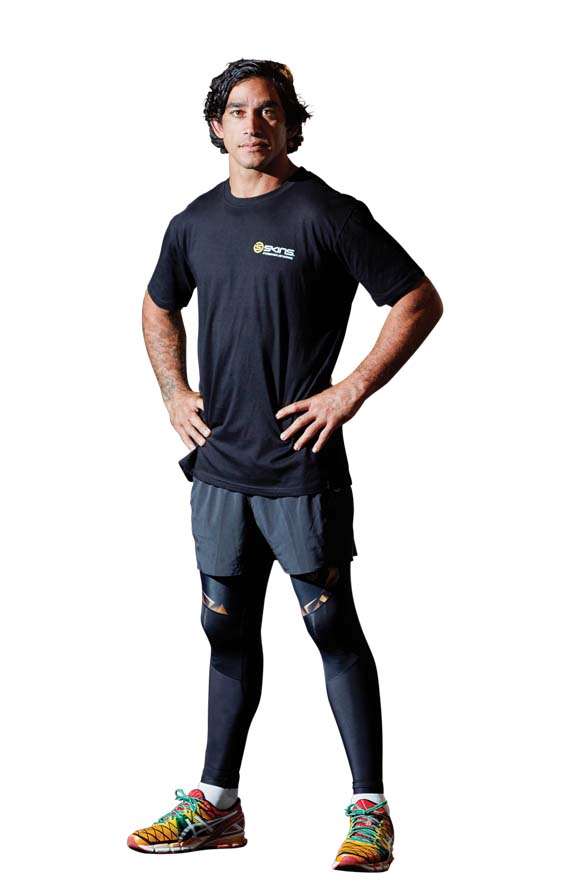

To Thurston, playing rugby league at the elite level is a whirlpool of physical and emotional pain, triumph, heartbreak, glory. For him, each game means an investment of every ounce of determination he can possibly offer. “It’s no doubt a roller coaster; sometimes you just want to jump off it,” the three-time Dally M Player of the Year told Inside Sport at a Skins product launch in Sydney. “You’re constantly going up and down. But that’s what I love about it. I do invest a lot into the game, but I wouldn’t change it for the world. I’m in a privileged position. Rugby league has given me more than I would ever, ever have dreamt of.”

Canberra Raiders coach Ricky Stuart argued in one of the Sydney dailies a week after the Beau Scott controversy that Thurston should take the late hits and the dangerous throws as a mark of rugby league-style respect (cold comfort for Thurston, we’re sure). Stuart offered that rivals are doing this to the Cowboys half because they’re aware of his level of determination and desire to keep going after the hit. According to Stuart, if oppositions thought JT was a diver, an injury-faker, someone who stays down after the hit, they wouldn’t be charging at him the way Scott did.

Maybe Stuart is right in some perverse way. Because the day Thurston finds himself being left alone by defences is the day they’ve found a newer, more dangerous threat in attack – but that time won’t arrive for a while yet. The NRL superstar is considered by an ever-increasing number of fans and experts as the best player in the game. The voice of rugby league, Channel Nine’s Ray Warren, declared as much last year in commentary. Wally Lewis, legendary halfback Allan Langer’s greatest fan, couldn’t resist either after witnessing JT’s heroics last year. “I didn’t think I’d rate anybody above Alf, but boy oh boy, this man has taken the game to a new level,” King Wally told his TV audience.

******

Johnathan Thurston has collected 19 individual playing awards during the course of his career, which began off the bench for the Canterbury Bulldogs back in 2002. He’s been crowned everything from NRL Dally M Player of the Year, to world’s best player, to international halfback of the year and the people’s choice as best in the game. While he will never receive an official award for it, he is rugby league’s best on-field organiser, too – no questions asked. Look at how quickly he can have the Maroons and Australian backlines purring like a kitten after only a few days in camp. His engine rooms, too, always have a definitive direction about them. Expert rugby league on-field organisers aren’t born, they’re perfected over a long period of time. Halfbacks like Thurston know what’s coming up because they’ve seen it happen – and seen it come undone – thousands of times before. Their years of experience can prove as useful as a third eye into a dimension no one else can see.

Right across last year the North Queensland Cowboys were absolutely lethal within striking distance of the opposition’s stripe, running simple patterns in attack, all the while glued together by Thurston’s flat, fast and accurate passes. But as the great head-geared one told us, this kind of fluidity with the ball isn’t perfected overnight. “It takes many hours of practice, working on the structures that the coaching staff have put in place,” he says. “It’s my job to execute those structures. It helps when everyone knows their role in your team; you can execute your structures when you get in those certain areas. The last 12 months have been great for the club and hopefully we can take our game to another level.

“The work is continual, but in saying that, it’s about not getting bored of the same old skills and the same old drills. You need to be at your best on the training paddock. That’s what we’re trying to drive at – being your best every day and making sure you’re the best when it comes to training. What you practise during the week, you’ll put into practice on the footy field come game night. If you’re practising bad habits and teaching yourself bad habits, they’re going to surface in matches and that’s what we’re trying to eradicate from our game.”

Any rugby league player can throw a dummy pass. But not everyone buys one ... except when Johnathan Thurston is the salesman. The dummy he sells opponents is the most deceptive in the game. On the run, he doesn’t just position his arms to throw the ball, he’ll morph his entire body into a shape that says “I’m about to throw it – but where?” His ability to maintain his running speed when reforming after faking to pass keeps the attack fluent and the opposition resetting on the run.

As it has been for years, Thurston’s passing game was clinical, intelligent and accurate throughout 2014. His ball-receivers start off each play as part of the background scenery. Defenders don’t notice them until they’ve hit a yawning gap which Thurston has seen them running towards. According to the old rugby league adage, attacking players should run at spaces, not faces. With this in mind, one of Thurston’s greatest attributes is his ability to detect when his team-mates are about to spot a clear corridor to the try line. How do you defend against that?

Thurston’s kicking game across the face of goal to his outside centres and wingers is second to none. His kick-receivers usually catch his high balls in the opposition’s in-goal area, negating their need to make further metres once they’ve made their catch. His kicks in goal, whether grubbers, bombs or cross-field punts, resulted in 21 forced drop-outs in 2014, the most by any half.

In general play, Thurston’s change in direction is among the quickest in the competition. His acceleration off the mark from a standing start, too, belies his 32 years. Witness the end of the Cowboys’ season last year. Their game against the Roosters was cloaked in controversy after a Cowboys' spilt ball was ruled to have gone forward before being picked up by Thurston, who sprinted away to score a “try” after the siren. There’s no technical way of describing his instincts that night. He tucked his head forward and bolted towards the vacant try line. “I remember looking around and one of the refs was going to blow his whistle and call it back, and the other one just let the play keep going. If I had’ve got tackled, would they have called it a knock-on, or would they have let play go on? We don’t know. I just went for that line and thought it was a try. This year we need to be better in certain areas of the game so that we don’t let ourselves get in those situations; those positions where, at the end of the day, the referees are doing their best, but decide our fate at the end of a game. We put ourselves in that position that night and we need to be better than that, so we don’t have to come back from 30-0 down to try to win a semi-final. You’re pushing shit uphill when you’re 30-0 down after 30 minutes. We showed an enormous amount of courage that night, but we weren’t good enough.

“That’s what’s driving us now. I believe it’s probably the best squad the club has assembled over the last two-three years. We just need to be better in certain areas of the game. We’ve been slow starters over the last three-four years, which has hurt us. We’ve had to win a lot of games over the back end of the year to scrape into the eight or into the four. We understand there’s a good opportunity there for us, but with that comes hard work.”

******

Beau Scott and his Newcastle Knights team-mates escaped suspension for their treatment of Johnathan Thurston at 1300 Smiles Stadium earlier this year, but it could’ve gone horribly wrong for them. A late hit is a late hit, and if a player is severely injured after copping one, the league’s judiciary can open its hearts up wide to victims by serving out harsh penalties to perpetrators.

Knock a popular player like Thurston to the ground in a late hit and you’re also faced with a PR war that’s impossible to win. Put simply, Thurston is one of rugby league’s greatest assets. He is grassroots, king of the kids. He is admired by grown men for that bravery ... and he and partner Samantha Lynch have just welcomed Charlie Grace into the world as a sister for first daughter Frankie, so the mums love him, too.

Thurston’s a rare case in that he’s a star who is 100-percent aware of the role of the role model in rugby league. Wide-eyed with amazement whenever in the presence of rugby league stardom when he was knee-high, he knows very little has changed since. He knows that young fans of the game don’t care how much money a player is worth, or how important an NRL star considers himself. If nothing is given back to the fan, less love will be exchanged in return. “I was probably about 12,” Thurston shared with Inside Sport. “Me and three mates went and watched the Broncos play someone at the old ANZ stadium, QEII. After that game had finished, I remember playing footy on the actual field in the in-goal area; we ended up sneaking on there and played for about half an hour. I also remember how the players used to come out into a function room to sign autographs, meet the fans, things like that. I remember getting Dell’s [ex-Broncos, Dragons and Wallabies player Wendell Sailor] autograph. I suppose moments like that resonate with me with what I do now; handing my headgears and kicking tees out. Maddison gives me two headgears for every game; I can hand one out at half-time and one at full-time. The kicking tees as well, I get a heap of those and sign them throughout the year and after every kick I get the ball boy to hand it to a young supporter in the crowd. Those kinds of things, kids never forget; just like I never forgot meeting Dell.”

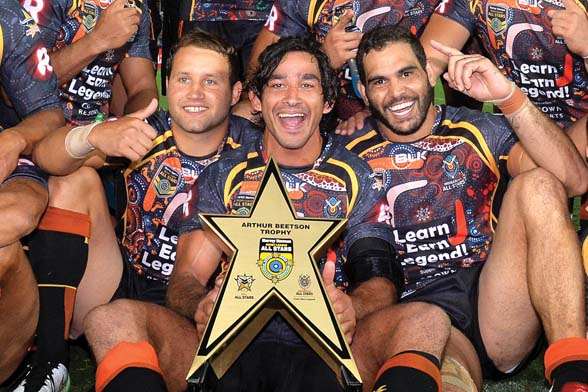

It is impossible to overestimate the inspirational value to Aboriginal children of a pumped up and proud JT playing in the Indigenous All-Stars jersey each pre-season. To his people, he’s a god; absolute representation of what can be achieved through hard work and pure passion. “The game of rugby league is very important to Indigenous kids,” Thurston says. “We’re using our game to break down the barriers that were previously there. I know the NRL has a reconciliation action plan that they’re implementing. They have some numbers that they want to employ with the Indigenous peoples in the NRL; they have a plan in place.

“I remember as a kid, we’d get home from school and kick the footy around in the back and front yard pretending to be Laurie Daley, Mal Meninga, you know, Kenny Nagas, Ricky Walford. No doubt that’s what kids are doing now. They’re out in the backyard thinking they’re GI, Justin Hodges and Sam Thaiday. So we understand the role that we play and understand how big it is within our culture as well.”

What struck a particularly raw nerve about that late hit and flip tackle by the Knights was that this is a player who has dominated at the highest level of the sport for so long, he is considered family by most north of the Tweed. The only player to have appeared in every single game for Queensland during its eight-straight State Of Origin series wins, it pains Queenslanders to see one of their bravest flat on his back after a cheap shot.

One of the only other times his worshippers would’ve seen him as physically damaged on the field was back in Game 3 of the 2011 Origin series. With the Maroons ahead 24-10 in the series-deciding encounter, which history shows they would ultimately take out, Thurston was wounded by friendly fire when his team-mate Ashley Harrison smothered JT’s leg like a roller moving over the nearby Gabba pitch. The pair was in pursuit of Blues enforcer Anthony Watmough. The injury not only floored Thurston for the rest of the game, it seriously wounded any chance the Cowboys had of holding onto their spot in the NRL’s top four. Hearing the sounds of celebration of another series victory from within the confines of the Lang Park sheds, Thurston planned on awaiting the arrival of his winning co-Maroons after they had completed their parade lap (this was veteran skipper Darren Lockyer’s final Origin game, after all). But Thurston’s coach, Mal Meninga, had other ideas. When JT was pushed out onto the field in a wheelchair minutes after full-time – an ice pack which would have sunk the Titanic attached to his knee – Suncorp Stadium erupted in wild appreciation of its wounded hero.

Friendly fire it may have been, but Thurston was brought down as part of the battle that night, the way it should be for all players, in an ideal world. He wasn't taken out of play an eternity after he’d passed the ball, like he was against the Knights.

Yep, it has to be a serious slam to take Thurston out. He just keeps getting back up. That’s why he’s so often targeted. Indeed, that bravery of his has proven his Achilles’ heel time and time again. Just about his only one, though.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.jpg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)