The race is on to build a better wave.

ELEVEN-TIME WORLD CHAMPION KELLY SLATER has been on the professional surfing tour since 1990 – so when he called the closing day of this year’s Billabong Pro Tahiti back in August the “greatest day of competitive surfing in my life”, it was quite a statement. The break at Teahupoo was at its heaving, massive, tubular, pristine best – and the level of surfing had everyone agog at the athletes’ skill and courage. Slater surfed three times on the one day, racking up near-perfect scores all the way through, until he was bested by just three one-hundredths of a point in the final against Brazil’s Gabriel Medina. Onlookers were unanimous: this was epic. Even, in surfspeak, “all-time”.

But it wasn’t epic a few stops back when the tour landed in Brazil for the Billabong Rio Pro. This contest was held in waist-high crumbling mush – a beachbreak torn up by strong onshore winds. The world’s best surfers are always astounding, but these waves were like inviting the world’s best F1 drivers to an event, then handing them the keys to a fleet of Barinas. For a country that was about to host soccer’s World Cup, then the Olympics in two years, and maybe see its first surfing world champion crowned, it was a fizzer.

It has forever been the bane of surf competition organisers: they can micro-manage every aspect of a tournament these days, right down to jet-ski assists to save paddling time, and live on-line broadcasts of every event on tour. But if the waves don’t turn up during the two-week competition window, it’s a dud. They’ll still run the comp – even if it’s puny. Which can be embarrassing.

But now another surf competition is underway: in secret labs around the world it’s the race to produce the first fabulous artificial wave. In a pool. And, crucially, a wave that will, at last, see us determine who really IS the best surfer – and not just the person who catches the best waves ...

Back in the early ’60s, when the sport was riding the wave of popularity post-Gidget, surfers dreamed of an “endless summer” – travelling the globe in pursuit of warm water and long, peeling walls. These days the sport’s visionaries are taking over water research laboratories and building scale models of endless waves.

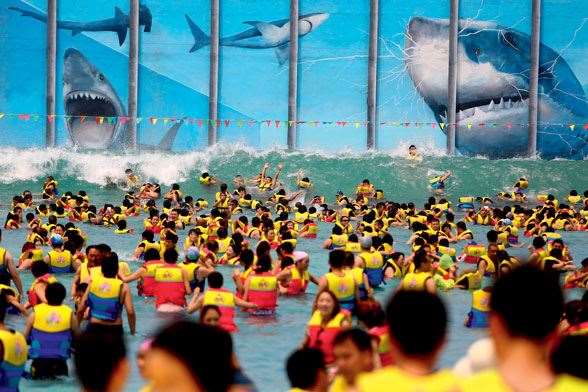

A consistent, repeatable, artificial wave? What’s so hard about that? Just get yourself along to a Wet ’n’ Wild these days and you’ll find a pretend beach with pretend waves dribbling towards the shore – they churn out “repeatable” mush all day long. Or get along to Dreamworld and check out the Flow Rider; they even install these on cruise ships. Flow Riders simply project a carpet of water across a moulded surface at speed. Riders can manoeuvre finless boards (or boogie boards), simulating certain surfing moves. But aesthetically the Flow Riders leave a lot to be desired: the “wave”, such as it is, is never smooth, and the engines used to blast the water are loud and use a lot of power. They look like fun – for a while. For a sport like surfing, where adjusting to the changing conditions of a wave in a natural environment is a big part of the beauty and challenge of the sport, the novelty soon wears off.

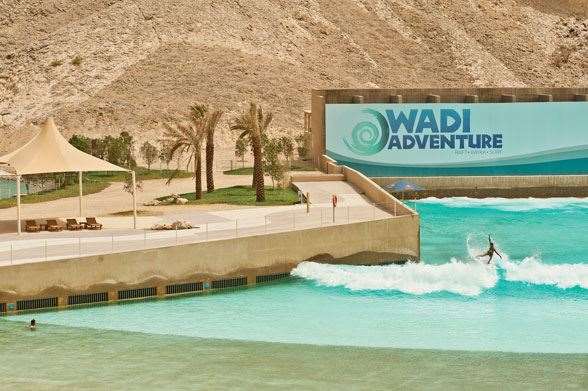

No, surfers want a wave that unwinds and tubes like a point break. In the desert of the United Arab Emirates, they’ve produced one that got everyone in the sport excited – for a while there. In a pool about 100 metres in length, it generates a surging swell that rolls forward onto an artificial beach, with a workable wall crumbling into closeout foam as it hits the shallower water. Since the Wadi Adventure Pool opened three years ago, it has hosted a succession of the world’s best surfers keen to test it out. It definitely tends to suit the sport’s “new school” – those who can gather enough speed to launch their boards into aerial manoeuvres at the wave’s end. And their performances are impressive enough to have surfers salivating. But the wave is barely a metre tall, and the riders say the break lacks power and shape – the speed and amplitude of their manoeuvres is severely restricted. And the energy required to produce the wave is massive: the swell is manufactured by displacement – using a hydraulic system. Water is banked up, then released suddenly. You’d have to be an oil sheikh to be able to pay the electricity bill. For a wave pool to be deemed commercially viable, it must be able to satisfy (and exhaust) a host of riders – not just a handful.

Strangely, the world’s best artificial surfing wave can be found in the Basque region of northern Spain. Welcome to the Wave Garden. Here, we can glimpse the }feasible future of the wave pool – and its secret all comes down to the generation of the swell. This wave isn’t produced by any single, sudden release of energy; while its technology is soundly protected by patents, we do know that the wave is generated by dragging a “hull” down the length of the pool, beneath the surface. As this “dozer” displaces water, the wave is created, then breaks along the moulded bottom of the pool – much in the way that some surfers are known to ride the wakes of large vessels in closed river systems; on the north coast of NSW, for example, some surfers wait for the passage of fishing trawlers and ride their wakes as they break along river banks – small, but perfectly formed. In Texas, they ride the wakes of oil tankers as they break on sandy shoals.

The Wave Garden follows the same principle – making it markedly less energy-intensive than other systems, and producing two peeling breaks down the length of an artificial lagoon.

It’s only a prototype, and the wave isn’t big enough to create a rideable tube or produce big manoeuvres, but it does allow surfers to throw their boards about – and it is all about potential. There are currently plans for Wave Gardens to be built in several locations around the world on a larger scale.

But this is no “endless” wave ... For that to happen, boffins like renowned Australian surfboard shaper Greg Webber have been thinking outside the square ... in the shape of a circle. His vision has been tested for the last six or so years in the water research laboratory of the University of Tasmania: an endless circular wave, with its swell also created by a patented underwater “dozer” displacement system. Webber and his colleagues presented their plan to last year’s Surf Park Summit – yes, there is such a thing: a meeting of minds, and entrepreneurs, held in California. You can see the “artist impressions” of his vision on this page – a surf arena, if you will, complete with ticketed seating, where the world’s greatest surfers will gather to ride waves well overhead in size, with the speed and power of the wave controlled by the touch of buttons.

They’re confident in the theory – it has been tested for countless hours in the lab. Now all they need is someone with the cash to get behind their vision and build one.

Any takers?

Kelly Slater himself is also associated with another outfit planning a new-school wave pool, though the mechanics of his technology is shrouded in mystery, while plans to build one in the hinterland of our own Queensland Gold Coast came a cropper two years ago as the developer wiped out.

Slater is a thoughtful visionary on the future of surfing, and sees the sport’s potential in such a pool. But as he admits, he wants to see one built mainly so he gets to ride it first. If it ever happens, the rest of the world’s surfers will be forming a very long line behind him.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.jpg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)