A decade ago, Roz Savage, a 34-year-old London office worker, decided to undergo an odd piece of self-: analysesshe sat down and wrote two versions of her own obituary.

A decade ago, Roz Savage, a 34-year-old London office worker, decided to undergo an odd piece of self-: analysesshe sat down and wrote two versions of her own obituary.

Protective Gloves worn through... Images: Courtesy of Roz Savage

Protective Gloves worn through... Images: Courtesy of Roz SavageThe first was the obituary she wanted read at her funeral – a rollicking yarn of adventures and risks, of spectacular failures and glorious successes. The second was the obituary she was heading towards – a conventional spiel of safety and comfort, of dull achievement and stale ease. When she’d finished writing, she sat at her desk and wondered at the difference between the two. She decided something had to change.

Gradually, she began to slough away the luggage of her old life, the stuff that was anchoring her at bay. “I felt I was getting a few things figured out,” she says. “But I was like a carpenter with a brand-new set of tools, and no wood to work on. I needed a project. And so I decided to row the Atlantic.” In 2005 she pushed off from the Canary Islands and heaved the oars until she nosed into Antigua. After that she shifted her sights to the Pacific. In ’08 she rowed from San Francisco to Hawaii, in ’09 from Hawaii to Tarawa, in ’10 from Tarawa to Papua New Guinea. In numerical terms, the crossing of those oceans equates to 12,800 kilometres of rowing, three million oar strokes, 312 days alone at sea. And she’s not done yet. This month she’ll row from Perth to Mumbai, adding the Indian Ocean to her resume. In 2012 she’ll row from New Jersey to London, completing her circumnavigation of the globe. It’s not all a quest of self-discovery; as a United Nations Climate Hero her voyages are also aimed at raising awareness of the dangerous amount of rubbish that’s emptied into our oceans.

Going Alone

“I’m always being asked: why go solo? Well, there are many reasons. I’m pretty happy in my own company – although when on dry land I love being around people. It’s nice to have the contrast between the solitude and the sociability. I also want to prove to myself that I can do these big challenges on my own. Being a lazy person, I know that if I had a crewmate, I’d end up letting them do the bits I don’t want to do, so going alone forces me into new learning experiences I may avoid otherwise.

“Beyond this, there are a lot of decisions to be made – not just during the row, but about aspects of the boat design, the course to row ... Being alone avoids disagreements and resentments over compromises. I know that when I’m stressed and tired I find it hard to be considerate towards another person. In this respect I find it easier to be alone than to have company. If there’s ever a mutiny on board, I’ve definitely been on my own for too long ... ”

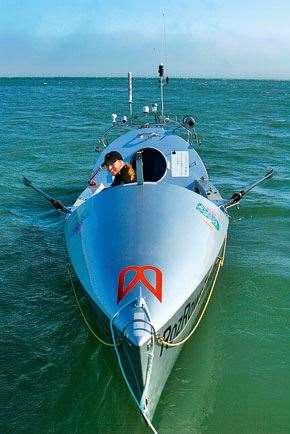

Nothing high-tech about her boat. Especially its engine. Images: Courtesy of Roz Savage

Nothing high-tech about her boat. Especially its engine. Images: Courtesy of Roz SavageStarting Out

“For the Atlantic I trained really, really hard. I was determined there’d be no surprises for my body when I arrived at the start line. So I trained for up to 30 hours a week – a combination of running, cross-training, weight training and many hours on my WaterRower.

“My training peaked two months before I left. For five consecutive Sundays I spent 16 hours on the rowing machine, rowing four shifts of four hours with a one-hour break in between. I’d start at noon on a Sunday and finish around breakfast on a Monday. It was as much about training my boredom threshold as anything else. I passed the time listening to music and visualising what it would be like to row across an ocean.

“Was it a successful strategy? Yes – in that it got me to the start line believing I had the physical stamina to cope with this challenge. No – in that within the first week I developed tendonitis in my shoulders and spent most of the crossing relying on painkillers.

“The problem was due to the fact that the rowing motion on the WaterRower was consistent and regular, while in the open ocean I was lucky if I got both the oars in the water at the same time and those shockwaves were transmitted straight into my shoulders. I found that while a rowing machine stroke derives 80 per cent of its power from the thigh muscles, on the ocean I was using my upper body much more. The rougher the water, the less I was able to use the bigger, stronger thigh muscles, and the more I had to rely on my lats and deltoids.

“For that crossing, it would probably have helped if I’d spent less time on the rowing machine and more time in my boat, but the boat was in the boatyard being fitted out, so this wasn’t an option at the time. There are also significant logistical challenges with getting the boat in the water on a regular basis – having a vehicle with a towbar, finding a boat ramp, having an escort boat in case of a strong headwind. It’s not that easy to get out in the boat whenever I like. Training in an open water sculling boat would’ve been a good alternative.”

Learning the Craft

“Probably one of the best things I did during my preparations for the Atlantic was to spend a total of six weeks at sea in relatively small sailing boats. For four weeks I sailed on a Sigma 38 in the Eastern Atlantic, from Cape Verde to the Azores. The plan was then to sail back to the UK, but the weather was too hostile, so we just did a two-week loop to the north of the Azores. These six weeks gave me invaluable experience in a whole range of things: using marine instruments, developing navigation skills, keeping watch overnight, the psychological impact of being out of sight of land. And, of course, it gave me a good taste of sea-sickness and how to survive it.”

San Fransciso To Hawaii Images: Courtesy of Roz Savage

San Fransciso To Hawaii Images: Courtesy of Roz SavageSettling In

“Since then I’ve adopted a much more relaxed attitude to training. Now I spend between 30 and 90 minutes a day in the gym, depending on my other commitments. It’s pretty much a ‘fitness for life’ philosophy; the kind of training that any person would do to keep their body relatively fit and lean.

“In a routine week I’ll do a cardio session each day. In those sessions I like to break it up by doing intervals – between 30 seconds and 5 minutes at higher intensity, before taking it back down for a recovery period. I use a heart-rate monitor to track my effort level, aiming to get into the 140-170bpm range for the higher intensity intervals. Each of those sessions normally lasts between 40

to 60 minutes.

“As well, I’ll also do six weight training sessions a week, focussing on different sections of the body each session: legs and abs one day, back and shoulders the next, and so on. I typically do 12 different exercises, one set of 15 reps each, at the maximum weight I can manage for this many reps.

“Of course, there’s rarely a ‘routine’ week. I try to do my workout first thing in the morning, before I log onto email and get overtaken by distractions. If I have an early start, I try to do at least something – a quick cardio workout, a few push-ups, a few crunches ... Just something to make my body feel challenged.”

Beating Boredom

“The main challenge in my training is boredom. I’ve run a couple of marathons and the biggest challenge is your mind. I find negative thoughts just bubble up – like when you’re ten minutes into a three-hour training run, and you’re already thinking, ‘Bored, bored, bored.’ The psychological aspect is just huge. You just have to believe that the determination to succeed can overcome physical shortcomings.

“If all else fails, podcasts, audiobooks and good music all help distract the mind. Recently I’ve also enjoyed using some iPhone apps to help motivate me – CrunchFu, PushupFu and SquatFu set me targets, count my reps, tell me if I’m falling off full range, and give me a grade at the end. If I’m struggling for motivation, having a robot tell me what to do somehow eliminates the option to wimp out early.”

Roz Savage Portrait Images: Courtesy of Roz Savage

Roz Savage Portrait Images: Courtesy of Roz SavageMoulding the Mind

“I use a variety of techniques to deal with the mental stress of rowing long distances. Firstly, I find it important to properly define my motivation. I need to understand exactly why I’m undertaking this challenge, and what rewards it will bring me when I succeed. Secondly, reading about people who’ve had really tough times in the wild – Ernest Shackleton, Aron Ralston, Ranulph Fiennes, Joe Simpson – helps me to remember there’s always someone worse off than myself!

“But probably the most important technique I use is to ‘focus on the process’, to know what needs to be done today to bring me closer to my goal. So I’ll have a very vivid image in my mind of the goal itself – how it’ll feel to arrive at the end of the journey, how this fits into the bigger picture of my life direction – and I know what needs to be done in the here and now to reach that goal. I refuse to contemplate tomorrow and all the other days that will pass between where I am now and where I want to be. I just find that too overwhelming. I concentrate on taking it one day, one stroke at a time.”

Fuelling the Engine

“I eat really healthily at sea – unlike on dry land, unfortunately! And I try to keep my environmental footprint small by using unprocessed foods as much as possible. Foods also have to be long-lasting, uncrushable, light, compact, and full of calories. So I eat wholefood nut and seed bars, nuts, dried fruit and occasionally freeze-dried expedition meals. I also grow my own beansprouts onboard, using peas, beans and lentils in an Easy-Sprout pot. These are real superfoods, full of vitamins, enzymes and fibre. I mix them up with some tahini, almonds and nama shoyu sauce and eat them with crackers. Yum! But despite all this good food I still tend to lose 11kg on each ocean crossing – then regain 14 on dry land ...

“Water-wise, I have a Spectra water-maker that converts saltwater into freshwater by forcing it through a series of increasingly fine filters. I also take 75L of freshwater which serves a double purpose as emergency supplies and ballast to help keep my boat upright.”

The Trusty Steed

“It makes me wince when people describe Sedna [my boat] as a ‘high-tech rowboat’. She’s really just a basic boat, with an extremely low-tech engine – me. I do have technology on board, sure, but it doesn’t make the boat go any faster. Recently I actually decided to change the colour of my boat. My theory is that you can make anything appear high-tech if you paint it silver. So I’m going for the reverse effect – a nice, low-tech, highly spiritual purple.

“I communicate with shore by satellite phone. I also use the phone, connected to a laptop, to send emails and post blogs. On the Atlantic the phone stopped working 24 days before the end of my journey, so I lost all communication. No weather forecasts, no blog posts, no calls to my mother. Strangely, though, I loved it. Not many people have the opportunity to experience such complete isolation, peace and quiet.”

Related Articles

Morri: Golf at Riviera is golf worth watching

Review: Titirangi Golf Club