Yep, we still have the world’s most determined athletes ‒ and the best metaphor-producing rowers going around.

Photos by Warren Clarke

Photos by Warren ClarkeYep, we still have the world’s most determined athletes ‒ and the best metaphor-producing rowers going around.

Anyone else growing tired of hearing how “great” Great Britain is going to scoop the medal pool at its home Olympics in a few months’ time? Sure, it used the loot from its national lottery to boost its chances in tech-reliant pursuits such as cycling and sailing, but we reckon Australia still has athletes the envy of the world when it comes to the “priceless” virtues of true grit and stamina. Rower Kim Crow is a fine example. Crow, 26, the daughter of Max, a 200-plus gamer for the Bombers, Saints and Bulldogs, is a cert to be picked for Australia in the women’s double scull for London. She’s done us proud at five World Championship regattas, and her efforts at the Beijing Games only confirmed her role as a cornerstone of Australia’s next Olympic assault.

“We have the World Championships as a stop-check as to how we’re going, but our real focus for the entire time is very much on the Olympics,” Crow told Inside Sport before taking us through a training session on a wet ‘n’ wild late summer morning in Canberra. “Even at this point in time, where we don’t have crews finalised for the Games, we’re at a very advanced stage of our Olympic preparation.

“We talk about the first year of Olympic prep as getting together the cake mix; the next year is preparing the cake and putting it in the oven; and now that we have taken the cake out of the oven, we’re just putting the icing on top.”

Yep, we still have the world’s most determined athletes ‒ and the best metaphor-producing rowers going around. Here’s how pure ability and hard work will get our girls over the line against those big-spending Poms in London.

ROWING 101

“Rowing races are conducted over 2000m. There are two different categories: sweep [one oar for each rower] and sculling [two oars each]. Most of us can do both ‒ I raced sweep in Beijing in the pairs, but since 2010, I’ve been sculling. My change was a strategic move by the powers that be. They wanted to strengthen our sculling program and encourage a lot of other girls to come over, rather than dilute the talent across the two disciplines.”

TEAM GAME

“I began my career in the women’s eights. Over time I’ve preferred the smaller boats; I like the dynamic you have of working closely with one other person. You go into a race knowing you’re playing a big role in the outcome. Personally, I feel there’s a better chance of winning a gold medal in the smaller boats, too, which is what I want at this Olympics. The world record for the women’s double scull is six minutes, 38 seconds. We’d be expecting to be somewhere near that depending on the conditions.

Photos By Warren Clarke

Photos By Warren Clarke“In saying all that, when you have a big boat going well, the actual feel of it running across the water is pretty amazing; it’s quite a magical thing to be a part of a bigger crew.”

TALL ORDER

“It helps to be tall as a rower; the leverage you have is an advantage. If you aren’t tall, it doesn’t mean you can’t be successful on the world stage, but you need to compensate for that in other areas: for example, you’d have to be stronger or super-fit.

“Am I tall for a rower? I’m 189cm ... I don’t often notice that I am tall, but then I go out in public and I think, ‘Yeah, I am actually quite tall.’ All the male rowers down here are much taller than I am, and quite a few of the girls are taller than I am.”

JOB DESCRIPTION

“In a double scull, you have a stroke seat and a bow seat. As a stroke, my job is to set the rhythm. I guess I’m the ‘driver’ of the boat. The stroke role is often seen as the more physical of the two, whereas the bow is the more technical. When I’m rowing with one of the girls who’s vying for the other double seat, I’m in the bow. My job there is to make the race calls, communicate, stay perfectly in time with my partner. To match her length, her rhythm, to make sure we’re cutting through the water at the same time.

“The bow is often the more experienced of the two rowers, just because there’s a little bit more responsibility in assessing how a race is going and feeling how the boat is going. Another advantage is that the stroke seat can hear the bow seat. The other way around, it’s a lot more difficult to hear because of the way sound travels and the way the boat is moving.”

RACE STRATEGY

“In rowing, you have quite different race strategies and plans, depending on who you are rowing with and against, and what boat class you’re rowing in. Quite often in the bigger boats, whichever crew completes the opening 1000m first, wins. The smaller boats are a lot more tactical. You have a lot more opportunity to respond to other crews and to actually race. I compare small-boat-rowing to a running race, where you can tactically manoeuvre yourself. Whereas in a bigger boat race you just have to pull as hard as you can for as long as you can

and hope you cross the line first.

“The crew who has been dominating the women’s double sculls for the past few years, the Brits, their strongest part of the race is their first 500m – I don’t think they’ve ever been beaten out of the blocks. That changes what our strategy might be or what other nations’ strategies might be.”

Photos By Warren Clarke

Photos By Warren ClarkeSTROKE, STROKE

“Rowing is one of those sports where we could sit and talk technique all day. We spend a lot of time with biomechanics dissecting force curves, watching videos frame by frame ... But the essence of the stroke is to get the blade in the water as far forward as you can; you want the longest possible stroke. We call that spot the catch; where the blade ‘catches’ the water. You want your catches to be clean and long.

“Then you have the drive phase of the stroke. That’s when the oar is in the water; when you’re applying all your force. You want to make sure your force is being applied evenly and not up and down. You want your blade tracking flat.

“Then you have the finish of the stroke, where you pull the blade out of the water. You want that to be as clean as possible. That’s where you get a lot of your boat run. The final part is the recovery, where you’re taking your blades back out to the catch. You want to make sure your blades are clearing the water.”

WATER WORLD

“A typical training row for us would be two hours. As rowers, we get through a lot of work; I think people are surprised at that, seeing as though the actual race time is just six minutes! It’s such a technical sport. There’s such an emphasis on being able to row really well and really efficiently. The best way to learn how to do that is by rowing lots of kays. We go out there and we do various drills, a lot of steady rowing, trying to implement the changes we want to be able to take into major racing meets.

“We do a lot of blade drills; practising how we might be taking the blade out of the water. We might do a double-square drill, where instead of feathering the blade once before putting it in the water, we might feather it twice. We’ll do that to practise what our hands are doing, and to practise our timing as well. We might do other drills, where we’ll slap the blade on the water before we put it in the water; that’s to practise the crew’s timing and our handling around the catch. There are a number of drills we do just to work on very minute segments of the stroke. Often we’ll go out for a row, do a session, come in, watch some video of the session and identify different parts of the stroke that may not be entirely in time or as efficient as possible. Then we’ll go out for another row and work on a particular drill that might help fix that component of the stroke, and start incorporating that.”

GET SET … ROW

“Our start sessions at training get everyone excited. We all love going out there and lining up and starting against each other. At the moment, we have a session on a Wednesday where we do six two-minute pieces, which is pretty much just lining up, side by side, going as fast as we can for two minutes. It’s great fun – just enjoying the buzz you get from racing.”

Photos by Warren Clarke

Photos by Warren ClarkeLEG WORK

“The power generated in our sport comes from the legs – this surprises a lot of people. When you watch rowing as an outsider, it does appear to be quite an upper-body-dominated sport. We often talk about the arms as just the linking rods; their job is to have enough tension to be able to pull the blade through the water, but all the work is actually coming from down in the legs.”

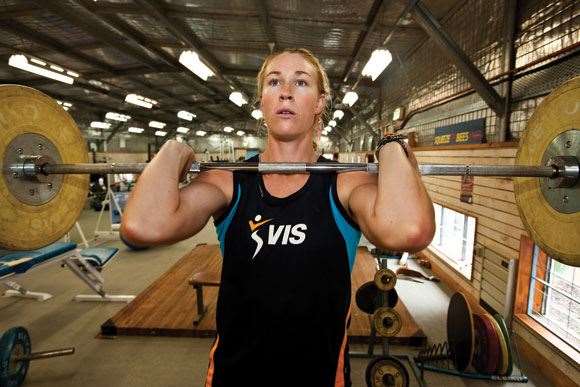

IN THE GYM

“We do a lot of deadlifts and squats in the gym ‒ real exercises to strengthen our glutes, thighs and hammies. Your body is meant to be able to hold the power in rowing. We do need strong-enough upper bodies as well to be able to hold the force going through our legs.

“The number of weekly gym sessions differs throughout the season and between different athletes. I spend a lot of time in the gym; early in a campaign its about five sessions a week for me. Early in the season our sessions are pretty long. Typically, I’ll be in there between two and two-and-a-half hours. Leading into racing, the actual strength component of a session is a bit shorter, but we do tend to have a lot of pre-hab and re-hab exercises in there as well. We use our gym sessions for the dual purpose of getting stronger and making sure we don’t get injured; injury prevention-kind of exercises can take quite a while.

“At the racing time of year, I’d be down to three gym sessions per week. The idea behind that is to put on a bit more muscle bulk, to gain a bit more extra strength. Some of the other stronger rowing girls down here spend extra sessions outdoors on bikes or running, rather than being in the gym.”

BY THE NUMBERS

“We do more work on the Ergometers early in the year. They’re a great tool to really get your fitness up: these machines don’t lie. We call the Ergo the ‘truth machine’. One of them in particular we call ‘The Ergo of Death’. There’s no other way of explaining it.

“At this time of year, we do two sessions a week on the Ergos. The wattage you sit on is chosen according to your physiology and your personal best performances. It’s chosen at a level that you should just be able to keep up with ... or not. You’re really working at a state where you’re short of breath, you’re producing a lot of lactate, your heart rate is at its absolute maximum ‒ really working out how you’re going to get the absolute best out of your body.

“We do six five-minute intervals with one or two minutes’ rest in between. It’s really about going at close to your maximum effort, having a very small break which isn’t long enough to settle your heart-rate or lactate, and then getting back into another piece at the same intensity and holding that, and holding that, and holding that ...

‒ James Smith

Related Articles

Sydney rower heading across the Atlantic

Molenaar's giving back to the sport she loves