This Aussie is breaking out of the shadows and heading his own assault on cycling's ultimate prize.

Photo by Getty Imagesa, the principality of Monaco seems like an odd place for a Tasmanian cyclist to set up base. The well-heeled, high-rolling, cocktail-sipping, white-shoe brigade isn’t exactly a snug fit with the almost-monastic life of a professional cyclist. But some of the best in the world live there, including a stack of Aussies – Matt Goss, Mark Renshaw, Simon Gerrans et al. Its central location, peerless climate, relaxed fiscal policy and access to some of the world’s most spectacular climbs makes it a no-brainer.

Photo by Getty Imagesa, the principality of Monaco seems like an odd place for a Tasmanian cyclist to set up base. The well-heeled, high-rolling, cocktail-sipping, white-shoe brigade isn’t exactly a snug fit with the almost-monastic life of a professional cyclist. But some of the best in the world live there, including a stack of Aussies – Matt Goss, Mark Renshaw, Simon Gerrans et al. Its central location, peerless climate, relaxed fiscal policy and access to some of the world’s most spectacular climbs makes it a no-brainer.At face value Monaco is a sandpit for the filthy rich, but 15 minutes on your bike and you’re in cycling heaven. Like the Col de Madone. The mythical beast climbs from sea level to almost a kilometre in the sky in no time. The road is far too narrow to have ever formed part of the Tour de France. But cyclists talk about it in hushed tones.

For it is the ultimate test ride. Lance Armstrong would rock up a fortnight before Le Tour. At the top would stand the reptilian Dr Michele Ferrari, armed with a stopwatch, a clipboard and heaven knows what else. If the Texan racked up certain numbers, he knew he would be unbeatable at the Tour. Tim Kerrison, Team Sky’s Australian physiological guru, was on hand last June when Richie Porte and his good mate Chris Froome ascended the mountain as quickly as anyone in recent memory. Kerrison walked away convinced that both were capable of dominating the sport for years to come.

******

THESE TWO inseparable team-mates and iridescent talents are a regular sight in these parts. They are both from regions of the world not often talked about on the French Riviera. When they first met, at the 2008 Herald Sun Tour, they were nobodies. Even today they look as though they could be blown off their bikes if a strong enough gale whipped up off the Mediterranean. Chris Froome is folically fraught, long-limbed, pigeon-chested and polite to a point. Off the bike, he resembles a mild-mannered CPA. Born in Nairobi, educated in Johannesburg, keeper of pet pythons, speaker of Swahili and wearer of Maasai warriors’ dress, he doesn’t cut the most imposing figure (“an X-ray on top of a pair of thighs” one French newspaper called him). But looks can deceive. Depending on who you talk to or what internet forum you log onto, he’s either the most talented, electrifying cyclist in the world, or juiced to the eyeballs.

Similarly, Richie Porte’s pleasant demeanour and lissom gait belies his street-fighter qualities. Not backward in dishing out a mouthful, the Australian can be quite blunt. He’s always good for a quote. In a sport that prefers to play its cards close to its chest, he always speaks his mind, doesn’t talk in code.

His journey to the apartment in Monaco was a rocky one. As a kid, Porte was a handy swimmer. Every morning and afternoon, six days a week, it was the same routine – up and back, up and back, following the black line, braving the Tassie winter chill. It takes a certain sort of personality to persist with that into adulthood. He tossed it in for triathlon, where he enjoyed a modicum of success. But he was no runner. His sporting hero was fellow Tasmanian triathlete Craig Walton, who was pretty much the same. Walton was built completely differently to Porte, but his races followed a similar pattern – go berserk in the swim and on the bike, then hang on for dear life on the run. However, with drafting on the bike legal, triathlon was inherently skewed towards the best runners.

Photo by Getty Images

Photo by Getty ImagesOn the bike, Porte was raw and untapped and definitely the wrong shape. But as soon as he tackled anything vaguely resembling an incline, he was untouchable. He was doing what he could to make ends meet – working as a lifeguard, a spare car parts courier and an Aussie rules boundary umpire. But could he make a living on two wheels? One thing was certain; as much as he loved the place, he had to get off the Apple Isle.

Porte eschewed the increasingly common route of the national institute, instead heading to Europe and tackling the Italian amateur circuit. It was cycling’s school of hard knocks. The culture shock was massive. Everyone was scrapping for a handful of professional spots. The Italian amateur scene was rife with performance-enhancing drugs. He was sleeping under a staircase. He was hit by a car and fractured his hip. He was ready to pack it in and head back home.

Another Aussie, Brett Lancaster, was a mentor and father figure of sorts during those lonely years. So too was the Italian Andrea Tafi, who was later caught in the net of retrospective testing from the 1998 Tour. Both recognised Porte’s immense talent and convinced him not to throw in the towel. His technical and tactical nous were decidedly amateur, but his V02 Max was in rarefied air. He was a quick learner. He was obviously going places.

Team Saxo Bank, under the auspices of the tainted Dane Bjarne Riis, liked what it saw at the 2009 Baby Giro. “You’re a good little rider and I’m going to give you a contract,” he said. But Riis took a tough-love approach. “You are too fat to be a bike rider,” he told Porte after the 2010 Paris-Nice. American Bobby Julich remembers a “lost puppy dog in the peloton ... always at the back”.

Porte shed the requisite kilograms, finally learnt how to descend and began to come out of his shell. When he won the time-trial at the Tour of Romandie, no one could believe it. “Do you think there was some sort of problem with the timing?” Riis asked. A fortnight later, he wore the maglia rosa at the Giro for three days. Suddenly he was the hunted. It was a typically lung-busting, mud-caked, drama-filled Giro. Bedevilled by diarrhoea and gastro, Porte was eventually reined in. But he had arrived.

The bourgeoning Team Sky came calling and his stocks continued to grow. Last March, Porte became the first Australian to win Paris-Nice, the iconic “Race to the Sun”. Runner-up in the Criterium du Dauphine, Criterium International and Tour of Basque Country, he has proved himself a pivotal part of what they call “The Sky Train”.

Right from the get-go, Sky’s ambition was as lofty as its budget. It wanted to steer a clean, British rider to victory in the Tour de France within five years. It realised its dream quicker than it could’ve ... dreamt. But the team wasn’t always popular. Too clinical, too calculated and too smug, the naysayers said. Sky was called the Manchester City of cycling. Like the infamous US Postal team, it would head straight to the front of the peloton and seek to control everything. It purported to be staunchly anti-drugs. Coaches, doctors and directors were given the boot after being implicated. On internet forums, in the press room and on the mountains, Sky was the subject of opprobrium and approbation in equal measure.

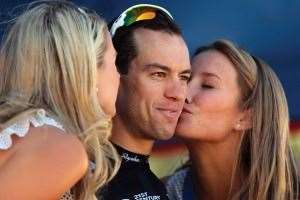

Best part of the job. Photo by Getty Images

Best part of the job. Photo by Getty ImagesTeam Sky’s generalissimo is Sir Dave Brailsford. The hard-nosed knight has masterminded the last two Tour de France victories, as well as 16 gold medals from the Beijing and London Olympic Games. Not a man to be trifled with, his mantra is “the aggregation of marginal gains”. At first, he and the team were ridiculed for their pettifogging ways. They would bring custom-made bedding to races. They would lay out non-slip matting on time trial stages. They would use fancy weather-modelling devices to locate appropriate training bases. There was meeting upon meeting. Everything, from the aerodynamics of their bikes to the way the cyclists washed their hands, was factored in.

When Bradley Wiggins won in 2012, Brailsford and Team Sky were criticised for being too robotic and too formulaic. With the aid of computer- modelling, team management plotted exactly what power numbers Wiggins and his wingmen needed at specific times. Bradley relied on being infinitely faster than everyone else on the time trials and being cuddled up by Froome and Porte in the mountains. A complex man and occasionally high-maintenance team-mate, Wiggins’ highs have invariably been followed by great lows. Beleaguered by poor form and knee injuries, his 2013 was a write-off. Kept on a leash the year before and hampered by years of lingering bilharzia (a blood parasite contracted during his childhood in Africa), Froome was ready to assume top billing. His little Australian mate would be the man to propel him to the mountaintop.

The 2013 Tour de France was a strange, compelling, altogether unprecedented race. It certainly seemed to signal a seismic shift. Whether this related to matters chemical or the lack thereof remains a matter of conjecture. The peloton would splinter in the blink of an eye. Champions were losing huge chunks of time, something we hadn’t seen in decades. For Sky, Froome and Porte, it was full of ups and downs. They were spat on, had urine thrown over them and had giant fake syringes thrust in their faces. They were constantly at the mercy of a rabid and once-bitten press. On the bike, they turned in some stinkers, as well as some hitherto unthinkable team and solo performances.

As the race headed into its second week, on the tarmacked slopes of Ax 3 Domaines, Froome unleashed one of the most astonishing rides in the history of the event.

Normally the first foray into the mountains sees a little bit of sparring but nothing too serious. However, Porte had played the consummate domestique’s role, chipping away at and breaking the challengers one by one. “They’re dropped!” Froome screamed with five kilometres to go and away he powered, evoking memories of Contador on Verbier in 2009 and a host of lab rats in the preceding decade. “I haven’t seen a day like this at the Tour for a long time now,” a clearly ailing Cadel Evans said afterwards. “That was a strange situation, a bizarre situation for the yellow jersey.” It was typical of half-muttered, pursed-lipped, asterisk-laden sentences of professional cycling. The inference was clear. Something was rotten in The Pyrenees.

More drama was to follow. High on Mont Ventoux, near a huddle of ski lodgings just before you enter the barren, exposed, lunar-like terrain, Froome unleashed another controversial and career-defining attack. The sheer violence of the move could only be fully appreciated by witnessing the sorry state of the field straggling in. Many of the premier Grand Tour riders of their generation had been blown off the mountain, losing ten, 15 and in some cases 20 minutes. Cadel’s Tour was now over. Contador had been reduced to a quivering wreck. The Colombian star Nairo Quintana, who had pushed as hard as anyone, appeared on the verge of hospitalisation.

Richie Porte (left), Chris Froome (middle) and Team Sky manager Dave Brailsford face the media before the 2013 Tour. Photo by Getty Images

Richie Porte (left), Chris Froome (middle) and Team Sky manager Dave Brailsford face the media before the 2013 Tour. Photo by Getty ImagesNot surprisingly, the press smelt a rat. It asked all the questions of Froome that it had baulked at with Armstrong. The French TV anchor, the preposterously coiffed figure of Gerard Holtz, shoved a microphone in his face and said, “Can you look me in the eyes, Chris Froome, and tell me you are clean?” The respected French coach Antoine Vayer calculated his power output and declared the result not merely suspicious or exceptional, but “almost mutant”.

At the following morning’s press conference, two-thirds of the questions pertained to doping. In contrast to Wiggins, who had gone off his head when posed similar questions 12-months earlier, Froome swigged from his water bottle and betrayed little emotion. But right towards the end, for one fleeting moment, he became irritable. “We’ve slept on volcanoes to prepare, we’ve been away from home for months, training together, just working our asses off to get here and here I am, basically being accused of being a cheat and a liar. That’s not cool.”

The problem was, we’d heard it all before. We heard it from Armstrong for years. We heard it from Stuart O’Grady, one of the most popular cyclists Australia has produced. We heard it from all sorts of sportspeople. In Marion Jones’ 2004 autobiography, she saw fit to spell it out in giant, red, capital letters: I AM AGAINST PERFORMANCE-ENHANCING DRUGS. I HAVE NEVER TAKEN THEM AND I NEVER WILL TAKE THEM. Just months after Armstrong had sought absolution with Oprah Winfrey, it was always going to be a horrible year to win the Tour de France. It was an even worse year to turn in a freak performance like that. The press had largely sleepwalked through the Armstrong era and was desperate to make amends. Team Sky was constantly obliged to prove a negative. Asked for the umpteenth time what he would say to embittered fans, Froome would sigh. “Believe me,” he said.

The truth is, no one really knows what to believe. But here’s a few sweeping statements. Tackling a Grand Tour is possibly the most arduous thing you can do in elite sport. If ever drugs could make a difference to your performance it would be in this sport. For years, professional cycling was a pharmacy on wheels. There are men currently riding and working on teams who have done dodgy things in the past. There are certain teams and individuals who will continue to transgress. But cycling’s governing body finally has a skerrick of credibility about it. The bio passport, the ADAMS database and the no-needle policy have all heralded significant change. When it comes to performance-enhancing drugs, cyclists are the most tested and scrutinised of all sportspeople, as they should be.

Most importantly, during the Armstrong epoch, there was evidence. There was the world’s most respected blood-doping expert insisting that the Texan had taken drugs. All around him there were cars packed with syringes, mass arrests at the border, whistle-blowers ostracised from the peloton, disgruntled former employees pointing at him and ostensibly fit young men dropping dead at 35. Right now, there is none of that.

So if they’re not doping, what exactly is going on here? Sky’s adherence to “reverse periodisation” training, which turns the standard preparation for endurance athletes on its head, is often touted. Cyclists, swimmers and distance runners have traditionally focussed on their aerobic base early in the season, before moving onto more high-intensity training. Much like the golden generation of Australian swimmers from a decade ago, Sky instead does an abnormally high volume of power and speed work, gradually increasing its duration. The upshot is that its athletes train at a frightening intensity. Froome and Porte both say the same thing – no Tour de France stage is as tough as a standard session in the hills beyond Monaco or one of their training camps on volcanic Spanish islands. It’s why, they say, they can spin a markedly higher cadence than any of the other teams. In Froome’s case, even on a hors categorie climb, he breaks away in a seated position, thus not compromising aerodynamics. You don’t need big muscles to spin a bike like that. But you need gills. And you need balls.

You also need a man like Porte. In Paris, he had the honour of leading the team onto the Champs Elysees. Froome paid tribute to his Aussie mate, saying he was probably the second best General Classification rider in the world. “Richie put all his ambitions aside in this race to keep the jersey on my shoulders,” he said. He certainly saved his bacon on a number of occasions. Porte had days when his legs felt like dog food, rough patches where more experienced riders tested his mettle. But he held his nerve. On the Col de Manse he was dropped on numerous occasions after thwarting more than a dozen attacks. On the descent, Contador crashed and very nearly took Froome out with him. Porte was there, ushered him back to the lead GC group and helped shore up his overall victory.

******

Richie Porte in front in the '08 Tour Down Under. Photo by Getty Images

Richie Porte in front in the '08 Tour Down Under. Photo by Getty ImagesLATER, ON Alpe d’Huez, Richie Porte proved his weight in gold. It was a hot day and the route was lined with drunks. They were pelting eggs at the Sky car. “Froome Dope” read one sign. Two men, each brandishing a giant “syringe”, ran alongside } Froome and Porte and squirted the contents into their faces. Then the unthinkable occurred. Froome bonked. It’s the word that cyclists fear most. “Sugar, sugar, I need sugar!” he gasped. Porte dropped back, securing the sugar-rich gels his team-mate needed. He incurred a minor penalty, but helped save Froome’s Tour. His adaptability and selflessness were obvious. Like Froome the year before, he looked like a man cut out for greater things than mere support roles.

But how long will he defer his ambitions? Closing down attacks, bridging gaps, fetching gels and carting the chosen one back into the race following crashes are all well and good, but you suspect he aspires to more than that now. So far he’s catapulted Froome to the Tour de France and a host of other races. But his time is nigh. His Sky contract winds up at the end of 2015, whereupon he will almost certainly go out on his own.

When he does, he’ll be under fire on multiple fronts. For this is the post-Armstrong sporting landscape now. These are cynical sporting times. Never again will we worship at the altar the way we did with Lance. When Porte becomes a team leader and if he secures a Grand Tour victory, they’ll be waiting for him – the French TV hosts, the drug-testers, the fans lobbing grenades on social media under the protection of nom de plumes.

Like Froome, you suspect he’s suitably unflappable and unaffected to let it all wash over him. The overwhelming impression, after all, is of a Launceston lifeguard living the dream. Running with that, if perchance you were travelling around Tasmania late in January, you may have caught sight of Porte whipping around the island with a big grin on his face. He and his mate clocked up 400km that day. Fuelled by Mars Bars, iced coffees and cheese scrolls, the pair set off at dawn and proceeded to circumnavigate Northern Tasmania. Afterwards, they cracked open a case of James Boags. It was Porte’s 29th birthday.

Pro cycling isn’t usually like that. The default expression on any cyclist is the grimace. Cycling is suffering. There are few things that can compare with ascending a hors categorie mountain at the tail end of a Grand Tour. Armstrong, or perhaps his ghost-writer, summed it up best. “Cycling is so hard, the suffering is so intense, that it’s absolutely cleansing. The pain is so deep and strong that a curtain descends over your brain.”

We know one thing, Porte is driven by what's good for the team. Photo by Getty Images

We know one thing, Porte is driven by what's good for the team. Photo by Getty ImagesFor some riders, Armstrong chief among them, one suspects it’s almost a form of self-punishment. With Porte, who clocks upwards of 40,000km a year on his bike, you suspect that it’s more a labour of love. Just five years into a professional career, it could just be that he is indicative of a cleaner generation. It could just be, in a sport where everyone stands accused, that he doesn’t give a stuff what people say about him. It could just be that he becomes the most heralded Grand Tour cyclist Australia has produced.

We really don’t know. But to see Richie Porte grinning wildly in the French Alps, while all around him capitulate, elicits a similar response as Usain Bolt larking about at the 60m mark of an Olympic Final. It’s akin to Froome raising an eyebrow as if to say, “Righto, let’s blow these chumps off the Alps.” It’s why we keep coming back, however tentatively. It’s the joyous brutality of what they do. We are right to be cynical. But believing is good for us. It’s cathartic. It helps keep us young.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open