Champion represented everything we wanted to believe was great about Aussie sport.

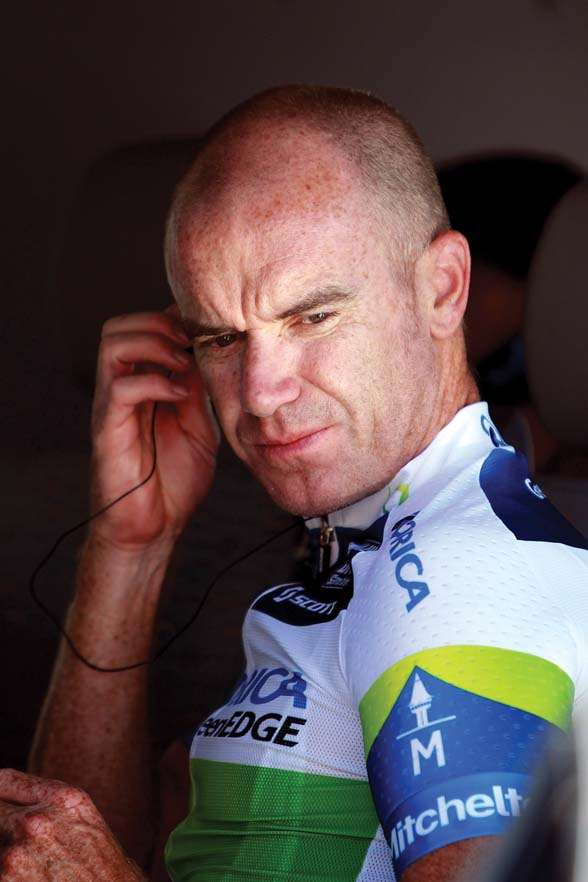

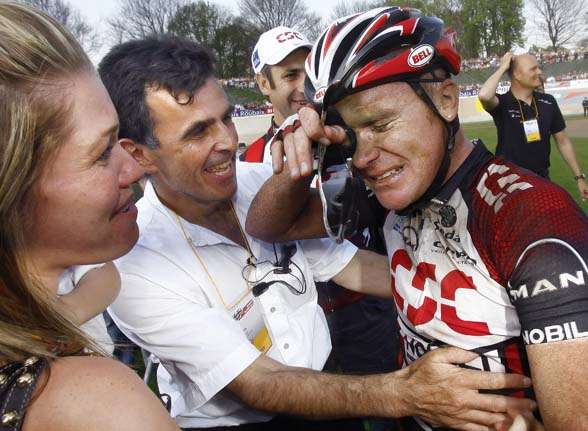

For more than two decades, since taking silver as a youngster in the team pursuit at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, Stuart O'Grady represented everything we want to believe is great about Australian sport. He wore Tour de France yellow jerseys, numerous rainbow jerseys, Commonwealth and Olympic gold medals (he attended six Olympics), and won probably the most famous brick in sport when in 2007 he took out Paris-Roubaix. But apart from those individual honours, there was also the impression of him as the devout team man, the guy at the pointy end of the peloton controlling the traffic, protecting his team's number one, guarding their interests like a doberman on wheels. But then came the fall. In 2013, Stuart O'Grady admitted that he had doped. He said it only happened during one brief period, in the lead-up to the Tour de France back in 1998, when he self-administered a course of the blood-booster EPO. He says the Festina raids and arrests during that race scared him, and he never doped again. He asks us to believe him, even though the admission only came in the face of imminent exposure. And yes, we want to believe him, too. Because Stuart O'Grady did represent everything we want to believe is great about Australian sport.

For anyone who doesn’t follow you on Twitter, what’s life look like for you now after all those decades' training and competing?

It’s looking very good, actually, quite normal. Whatever a normal life is ... Being home for a start. My life’s been pretty different to the average one, I guess. I’ve been following an almost military training regime for 20 to 25 years. And my bike was almost a part of me, you could say: everything I did in my life, I was always thinking about the bike. If I was having a barbecue with friends, you’d be worried about the next day’s training. It was just part of your life. So yeah, it’s been nice to hang the bike up on the wall and go out and just have a look at it ... It’s been a symbol of pain and suffering when I look at it, so I’m kind of happy to be home for the kids and the wife ...

All those hours during the day where you were once training, they’d be pretty handy for your golf game, wouldn’t they?

I like the thought of playing golf, but I’m very average. Back in the day when I was training a lot, I’d use golf as a getaway – you just turn the phone off and chase a silly ball around for four hours and not think about anything else. It was a good mental break. But now when I play golf, it’s a little bit more stressful because I realise I’m not that good.

What are you doing for a quid these days? Or does 20 years in professional cycling set you up for early retirement?

I’ve had a nice break: I came back and had a good year off. Now we’ve leased a heritage building in the Victoria Parklands in Adelaide and we’re creating a cycling hub. It’s going to be called the Velo Precinct – it’s underneath the old Victoria Park grandstand. We’re going to make that into a cycling centre, spin coaching classes, cafe and kids' playworld. So yeah, we’ve got a lot going on at the moment.

All based on your name?

Yeah, well, cycling in Adelaide is just getting stronger and stronger – you can’t believe the amount of people out riding these days. The Tour Down Under has had such a massive impact on this state.

Your career has pretty much run in parallel with the massive boom in cycling in this country over the last 25 years. What sort of differences do you see in the sport between then and now in Australia? Besides a lot more lycra on the roads ...

The whole sport has changed. It’s developed so much – 20 years ago when I was riding around here if you saw another person riding on the street you knew who they were, you know? Walk into a cafe in lycra and you got a lot of very weird looks. But these days it’s just absolutely amazing, and it has gone down through the ranks – there’s a lot better development squads, we have our own national road series which didn’t exist when I started, there’s team racing in Adelaide like there is in every major city. It’s progressed to a fantastic level, and we’re really getting some great bike riders: we’ve got junior world champions, girls and boys ... It’s just non-stop winning rainbow jerseys every year and that slowly filters down through the schools. We’ve got some fantastic riders coming through the ranks from South Australia.

So Adelaide’s looking like your future home? At one point in your autobiography you gave the impression that you’d like to go on to become a team director or something like that ...

If I’d stayed in Europe that would have been the obvious step, and I did have an opportunity to join a team before I left. But I kind of realised that would have meant even more travelling because directors still have to go to every race. Already I’d been doing 200 days a year on the road, and the more I thought about it, I was happy to get everyone back in Australia.

You were also a senior figure among athletes in the Olympic movement, and it looked like you might have had a future there in some way – but you’ve been forced to resign from the AOC Athletes' Commission. What else has your doping admission cost you?

I may have lost a few things – but that was about the only thing that was taken away from me. All the other organisations and people in the sport have been very supportive and kind of understanding to an extent. They’re not saying what I did was right – absolutely not. What I did was wrong – that’s the main fact. But I learnt from my mistake. Instead of going down that path again, I chose to make sure that no one around me ever went down that path – so I kind of just educated the guys and tried to show by example.

I think most people are pretty forgiving, once someone comes clean and just tells the truth about what they've done. But I imagine John Coates had to stand up for the principle.

Well, I did email John Coates and we had quite a good correspondence. I understood his points and he understands mine. Most people I’ve met haven’t been perfect human beings for their entire lives. There’s usually one stage when they were younger when they did something foolish which they haven’t told everyone about either. So I haven’t met too many perfect people. What I did was a mistake, I was stupid, and I won’t ever do that again, and that’s how I try and educate my kids and I think most normal people would do the same. You forgive, you move on and you try to teach people the right thing to do.

How do you feel, then, about those years after 1998 when you say you were riding clean when you were inevitably being cheated out of wins and medals by dopers?

To be honest, you just can’t base your thinking like that. You’ve got to hope that the organisations, the anti-doping organisations and the UCI, in our case, are doing the job. If you start doing any kind of sport thinking, “Man, I wonder if the others are cheating,” you’re going to do your head in. You’d go insane. So you just train, you do the best you can within your natural ability, and just hope and pray that everyone around you is doing the same.

Regarding forgiveness, should we forgive Lance Armstrong? He’s been banned from all competitive sport. Do you think his life ban was justified?

Yeah, I do. Yeah. I do. There are different levels of ... how do you say it? Different levels of cheating.

Industrial-scale cheating in his case ...

Yeah, you know, he had plenty of time to think about it. If he’d shown any kind of remorse or some kind of sorrow along the way ... but him just wanting to come out and compete in whatever event now, and the fact that he can’t do it, fires him up even more. But I think that the blatant, arrogant and bullyish behaviour that he showed to not only his team-mates but to his sport, yeah, personally I don’t think he should be welcomed back into the sport.

Were you ever friends with him?

Oh, he was friendly when he came to Adelaide and he needed someone to show him around. But it’s just another way that he kind of used people. He comes into their city, makes them feel special, and he was a legend of our sport, don’t forget. When the knock came on your door you answered it – that’s how it was.

Back to the bike, most of us inexpert viewers can work out who the best climbers are when we watch the big Tours, but we can’t really tell who are the best descenders. How much time can the best and gutsiest riders make on their rivals going downhill? Is it as important as going uphill?

It’s incredibly important. It’s a real skill and a real art. I mean, you’ve got guys who are absolutely incredible at it and then you’ve got guys who are brilliant at climbing, but then useless at going down. You’ve got to be really confident – it’s like downhill skiing: you attack the corners, you brake at the last minute, you don’t brake through the corner. The way I did it, you were 70 percent on the front brake and probably 30 percent back brake – the last thing you want to do is lock up your back wheel, because that means you’re skidding, and that means you’re going to go straight over the cliff. These are things you pick up as you go. But I’ve certainly had team-mates who were hopeless; you’ve really got to guide them down and get them right behind you and hopefully they have complete faith and confidence in you and follow you. But when you start getting wheels skipping around the corner sideways – for me I thought that was awesome, a lot of fun. But it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

And you can definitely crack open a field going downhill, right?

Absolutely. Though normally in the big races what’ll happen is that the team on the front with the yellow jersey will actually do the descent only as fast as their leader is comfortable. We actually went downhill a hell of a lot slower when we had the yellow jersey because obviously the last thing you want to do is cause a crash; it’s one of the unwritten rules in the peloton that you try not to break it up on the downhill unless that’s your objective. But there have been plenty of occasions where you might get to the top of a hill and you go “right, let’s put some stress on the peloton”, and you wind it up a bit.

In your book Jens Voight says about you: “I’m still trying to work out if he is a gifted descender or just a daredevil. I still haven’t worked out if he really does know what he is doing or if he just goes, ‘I don’t care – I just go.’” What’s the answer to that?

You know, I loved it. I really did love it. One thing I do miss in cycling is going down a mountain fast, like coming down one of the big mountains in the Pyrenees or the Alps and you’re doing 80 to 95 k an hour and you’ve got the whole road and there’s no traffic – it’s just the best feeling.

Where will you be watching this year’s Tour?

From my couch, hopefully. I’ve ridden the race 17 times and will be happy to be home watching it from the couch with a glass of red. I actually went over to the Tour de France last year as a spectator and to be honest, I couldn’t get home quick enough. It was worse than riding it. You’re driving and travelling and hotel rooms ... after a couple of weeks I packed up and came home. I went with a group of guys from Melbourne who go over every year. For them it was like their highlight of the year, but for me, it was like going back to school.

Tell us about Richie Porte? How good is he? Does he have a win in him, you reckon?

I know Richie really well. I actually got him his first pro contract with Bjarne Riis back in the day. I’ve known Richie for his entire professional career and he’s an absolutely incredible rider. He started late in his life, coming from triathlon, but he’s got massive potential. Though, I still think he’ll probably find that because he isn’t a seasoned three-week tour rider; he’s still going to have that one or two bad days in the big mountains. There is a big difference between seven-ten day tours and a three-week tour, and that’s something you train for, obviously. You can be incredible at one-week tours but three-week tours are just another special type of breed. I do think Richie will win one, but he might just take a couple of years to harden up his body that little bit more.

What sort of bloke is he?

Good guy. Typical little Aussie, Tasmanian. He’s good fun, good laughs. I caught up with him in Adelaide when they came down for the Tour Down Under and you can tell he’s changed – he’s a lot more focused, and obviously being with Sky brings a lot more responsibility. The bigger the pay cheque, the bigger the responsibility. I think he’s really enjoying the environment there and the pressure and hopefully he can crack a grand tour in the next few years.

But you’ll be rooting for Orica GreenEdge, right?

Yeah, I guess those guys have got most of my support. But I’m going for all the Aussies: Heinrich Haussler and Mark Renshaw and Adam Hansen and all the other guys – it’s just great that they’re up there and mixing it with them.

So about a dozen Aussies riding in the Tour de France this year?

Yeah, probably around the 12 mark, now that we do have so many Aussies with Orica. The more the better.

I’m sure you keep an eye on the young riders coming through. Any of them remind you of yourself when you were their age?

Well, you’ve already got a guy like Michael Matthews. I guess he reminds me of myself in a way – though he’s probably a lot faster than I was, he’s a tenacious character and has got to the podium in a couple of classics already, which is just a massive step. But a young guy coming through? Alex Edmondson from Adelaide. He has won the Under 23 Tour of Flanders. That’s a massive, massive win and shows huge potential for the future. There are just no races any more that Australians can’t win. Gone are the days where it’s like, “Ah, it’s too hard for an Aussie, because we don’t have cobbles or we don’t have 3000-metre mountains.” ... These days, nothing is impossible.

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Michael O'Connor still an asset to Aussie 7s squads

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)