How did an Australian teenager become the NBA Draft's man of mystery?

Photo by Getty Images.

Photo by Getty Images.AT THE NBA DRAFT, it’s known as the green room. The term is adopted, quite literally, from showbiz parlance – the waiting area for the performers before they take the stage. There was an actual room once, but it now more commonly resembles the floor at an awards night dinner. Very tall young men are clad in what are probably the first suits they have ever owned, and the outlandish sartorial displays speak to the dubious wardrobe choices made by young men chasing their first job. The prospective top picks, flanked by their family and friends, are gathered together to wait and hear their names called, go up to the podium and receive their welcome-to-the-NBA handshake from the commissioner. This is a happy moment, with an occasional sour hint – a staple subplot of the night is watching out for the last, lonely green room invitee waiting to be picked, the look on his face often mirroring his slide down the board.

At its most fundamental, the draft is a television show, a form of entertainment as structured as any three-camera sitcom. American professor Rick Olsen, who has written academic papers about the NBA Draft, says the elaborate ritual surrounding the entry of new players into the Association serves a powerful narrative purpose, encoded with themes of youths pulling themselves up by their high-top laces, as it were, to realise the American dream. It is the starting point for the NBA, perhaps the most star-driven of any league in the world of team sports, to mint its next wave of marquee names. At the same time, the draft provides hope for those starless teams at the other end of the spectrum, their fans’ faith kept alive by the notion that another LeBron or Durant will land in their arena. In basketball, a franchise player is truly that – one transcendent talent can be enough to change the fortunes of the sorriest team.

This year's NBA play-offs shape as one of the most intriguing postseason campaigns in years. But the story on the court has been subsumed by the narrative off it. A conspicuously gifted class of young talent has dominated the hoops discussion this year, across both the pro and collegiate ranks. Half the teams in the NBA were engaged in rather deliberate positioning – the league didn’t want it to be called “tanking”, preferring “bottoming out” – to secure a high spot in the draft, such were the riches on offer.

Befitting the game’s cosmopolitanism, this group hails from all points. The presumptive No.1, Andrew Wiggins, is a Canadian with an ex-NBA player father and former Olympic sprinter mother. The latest product of Chicago’s gushing basketball pipeline, Jabari Parker is the archetypal young guy whose game is advanced beyond his years. Joel Embiid is an uncommonly coordinated seven-footer from Cameroon who only started playing basketball three years ago – and when you apply economic thinking to the draft, good big men are the scarcest, and therefore most valued, resource of all.

Photo by Getty Images.

Photo by Getty Images.These three, along with a handful of others, are already well-known among basketball fans, playing for various high-profile universities and featuring atop the ubiquitous mock draft listings published throughout the year. But high up on those lists, one name has stood out as the exception, the unseen bolter who could be better than the rest of them. Dante Exum, 18, 198cm, by way of Melbourne and the AIS, is a first for Australian basketball – an entirely home-grown teen prospect good enough to go straight from high school into the NBA. But as with any reality TV show, he first has to get through the audition.

********

DANTE EXUM bears a well-known name in Australian basketball circles. His father, Cecil, was an American import who played for the North Melbourne Giants, Melbourne Tigers and Geelong Supercats during the NBL’s late ’80s-early ’90s heyday. Before coming to Australia, he had been part of the 1982 NCAA champions from the University of North Carolina, a team best remembered for a lithe 19-year-old: Michael Jordan, who Cecil knew from Carolina high school circles.

The elder Exum had begun conducting youth basketball clinics during his playing days, and continued in junior development around Melbourne after retiring from the NBL in 1996. Dante began playing at the Keilor Thunder club, and made the Vic Metro representative side. Very much on the radar of the AIS, he headed to Canberra on scholarship a year ahead of the normal two-year program. “Ironically, he was born the year I was coaching his father at Geelong,” recalls then-AIS coach Ian Stacker. “I knew of Dante at that age, but I had no idea of what sort of basketball player he would turn out to be.”

The kid who turned up at the Institute was extremely slight, average height for an elite guard, and shot it kind-of flat, but was already blessed with blazing end-to-end speed. “He could get to the basket with ease,” said Paul Goriss, an assistant coach with the AIS. “You could tell right back then there was definitely talent there, and it was only going to get better. But how good it got was anyone's guess.” There were early signs of promise. At the 2012 Under-17 World Champs in Lithuania, Exum was the Australians’ leading scorer as they claimed silver in the tournament.

Like many AIS athletes before him, Exum enrolled at Lake Ginninderra College, the Belconnen school whose sports’ program benefits the most from its proximity (about 4km) to the nation’s athletic incubator. Lake Ginninderra is used to high-level hoops talent passing through its halls: Lauren Jackson, Andrew Bogut and Patrick Mills all attended classes there. Allowed to take two AIS players on his team, Lake Ginninderra coach Jason Denley settled on Exum while he was still completing Year 10. “Not since Patrick had I seen a guard with that quickness,” says Denley, who coached Mills in 2006 and also works for the Institute program. “Dante’s time at the AIS, playing against stronger bodies, it was certainly a rapid growth during those three years.

“I had seen Patrick Mills come back from the various Boomer camps, and I could see Dante was performing at a very similar level. But he was still only 18.”

Exum had been marked out as a target for a major US collegiate program, and likely future Boomer. He talked enthusiastically about the opportunity to play in the spirited environs of college basketball, as his father had done, and visited several campuses in early 2013. The NBA, if it were to happen eventually, was still a few years away. But as the rest of the year unfolded, Exum would find his timetable moving up.

The Nike Hoop Summit, held in Portland, Oregon in April, is an all-star showcase for the best young basketball talent, pitting a United States team against a line-up drawn from the rest of the world. Exum, still a couple of months away from turning 18, was the fourth-youngest of all the players at the game; arrayed behind a bunch of players on the World side who would be NBA draftees two months later, he came off the bench.

All-star games can be most uncharitable – everyone is in it for themselves, not least a bunch of teens who are trying to capture the attention of professional teams. Exum was made to play off the ball, something he hadn’t had to do in years in Australia. With his first touch, he flew in off the wing and beat the defenders to the rim. It was a manoeuvre of supreme athleticism, on a floor full of supreme athletes. At the start of the second quarter, he picked off a pass on his own baseline, then proceeded to go the length of the floor for a fast-break lay-up.

Working on the television broadcast, ESPN’s global hoops guru Fran Fraschilla was utterly taken by Exum's performance. “With all the guys there, Dante took a backseat to none of them,” Fraschilla says. “He was one of the couple of best players, if not the best player, in the game that day. It was a revelation, maybe even a confidence-builder for him.”

The World team took control of the contest, and Exum punctuated it with a final minute that the talent scouts couldn’t forget. After making a circus-shot three-point play, he hit a long-range triple from the corner, then for good effect rejected American star Aaron Gordon’s lay-up off the glass. It was full-spectrum Exum: a combination of speed, length and basketball IQ, an example of the new breed of lead guards who could finish as well as they could distribute, like a Derrick Rose or Michael Carter-Williams.

By game’s end, the drumbeat had begun. Two months later, at the World Under-19s in the Czech Republic, Exum laid on another all-tournament showing, dropping 33 points in the quarter-finals, 21 in the semi and 28 in the bronze medal game. Goriss notes the Australians had encountered a fair heap of adversity leading up to the tournament – one of the key players on the team, Mirko Djeric, had even suffered an accidental gunshot to the leg – and Exum still led them to fourth place. Fraschilla was even more impressed at how he carried his team in Prague, tweeting: “Mark this down: Dante Exum could go in Top 5 next June.”

But while Exum’s peers headed for the harsh glare of bigger basketball stages, he found himself back at Lake Ginninderra. The potential shape of the 2014 draft morphed with every turn of the college basketball season. But one entry on those mock drafts held firm – Exum, away from view, with no bad news to drag him down.

The segment of basketball fandom that obsesses about the draft began hunting for any scrap of information. The Australian Schools Championship, held last December, had never attracted so much notice in the wider basketball world. The Bleacher Report, an American sports website, had sent a video crew to follow Exum during the tournament. The year before, Lake Ginninderra had lost the final of the championship in overtime to Caulfield Grammar. Even as a world of possibilities was opening up to Exum, he was still a high-schooler, motivated to win one with his class-mates.

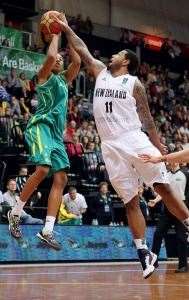

Boom time: Exum's rise earned a call-up to the national side, which beat NZ and qualified for the World Championships. Photo by Getty Images.

Boom time: Exum's rise earned a call-up to the national side, which beat NZ and qualified for the World Championships. Photo by Getty Images.“There were a number of Year 11 team-mates that were disappointed, so he made that decision at the time, unbeknownst to me, to come back,” Denley says. Lake Ginninderra indeed won the gold medal at the championships, as Exum, pretty much able to do whatever he wanted, conjured up a slick 15 assists in the final over Scots College. “After that final game, he found me out and said, ‘That’s why I came back, to help the team win gold,’” Denley says. “It was a knockout moment for me, which spoke volumes for his character.”

********

HIGH-SCHOOLERS can no longer go straight to the NBA. They did in the period between 1995 and 2005, among them names such as Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant and LeBron James. But for every star there was a bust, and the league, seeking to protect its teams from having to gamble on guys who had just attended their prom, put in a rule requiring eligible players to turn 19 in his draft year, and be one year removed from his high school class.

There is an exception for international players who have not played for a school in the US (Australia’s other bright prospect, Ben Simmons, will be subject to the rule because he is finishing high school in Florida). Exum, who will turn 19 a month after the draft, will be the closest thing to a high-schooler going into the league.

No previous Australian hoops prospect compares – all of them had multiple years of US college or professional experience before entering the NBA. Eleven Australians have been selected in the draft, starting with Luc Longley, the seventh overall selection in 1990. Andrew Bogut was picked right at the top of the 2005 draft, while Patrick Mills went near the bottom – the 55th of 60 – in ’09. Illustrating that the draft is not a be-all and end-all, the two other Australians currently in the NBA, Matthew Dellavedova and Aron Baynes, were not drafted at all.

The 1997 draft was a momentous one, with four Aussies chosen, led by Chris Anstey as the 18th pick to Dallas. As a seven-footer who could run the floor, Anstey had prized potential, but he was raw – he’d only been playing basketball for five years when he was drafted. For him, the draft happened at something of a remove; he was in the middle of an NBL season, which kept him from going to the US for the lead-up or draft night itself.

The pressure was still on. “Every game that I played for a period of three or four months, there was a row of NBA folders sitting there,” he says. “It felt like every single little thing I did was being evaluated: a missed shot, or jogging a lane, or if my body language was bad.

“The best game I had was the very next game after the draft, because it felt like a massive weight off my shoulders. I’ll never forget that game, against the Sydney Kings – it became fun again. I don’t think anyone enjoys being evaluated, trying to be someone they’re looking for. You certainly do feel like you’re under the microscope. With Dante expected to go a lot higher than I did, that microscope is looked through by more people.”

The Australian Boomers had heard about his physical skills - it was how he carried himself OFF the court that earned raves. Photo by Getty Images.

The Australian Boomers had heard about his physical skills - it was how he carried himself OFF the court that earned raves. Photo by Getty Images.Anstey is a keen observer of the Exum situation. He’s the coach of the Caulfield Grammar side that beat Lake Ginninderra; in his better-known sideline job with the Melbourne Tigers, he made an offer to Exum to train full-time with the NBL team, if he needed the option leading up to the draft. The Exum camp, which now includes the established NBA player agency Landmark Sports, representative of Kobe among others, decided instead to make the regulation play and keep a low profile. Exum is in Los Angeles, working with the trainer Tim Grover, known within basketball as the man who changed the shape of Michael Jordan’s body over the course of his career.

Once the college season ends in April, players who have declared for the draft go through a process of evaluations and workouts, some public and others quite private. Teams already have a solid idea of players from watching their games. These sessions usually are about trying to confirm or change impressions – for example, a player who didn’t shoot much from the outside for his college team, but would have to in the pros, will do shooting drills.

For lesser-exposed international players, the pre-draft process has traditionally had added weight. From initially looking down on prospects from outside the US, international players became something of a fad early in the 2000s. A good workout was sometimes enough to get NBA teams salivating.

One of the best-known is that of Yi Jianlian, the Chinese seven-footer considered one of the bright prospects of the 2007 draft. His agents invited representatives of NBA teams to watch his private workouts, which became notorious as Yi would demonstrate his impressive skills playing against a chair. After observing the workout, Boston general manager Danny Ainge quipped, “The chair played good defence a couple of times.” Yi was selected sixth overall, but was out of the NBA five years later.

“For awhile after Pau Gasol and Dirk Nowitzki started to play so well, we thought everybody coming over was going to be the next Gasol or Nowitzki,” Fraschilla says. “That’s changed: there’s much more thorough scouting of international prospects.

“There’s also a sense that playing in the NBA is very hard. Regardless of whether you come from Kentucky or Serbia, to eventually find an NBA player is never easy. It’s a hit-or-miss process. NBA teams are now trying to evaluate the international player in the same way they evaluate the US college player – see them as many times as possible, then get to know them.”

But as Fraschilla notes, Exum has been less seen than other draft prospects of his ilk. “Because nobody has seen much of him since last July, he’s still the mystery man. The agent’s job is to get Dante drafted as high as possible ... Dante has certain strengths and weaknesses, that if you haven’t done your homework on him, it will be awfully difficult to ascertain what they are. Dante’s in a position of strength.”

Word has been floating around that the Los Angeles Lakers, who will have a high pick after a rare down season, have guaranteed Exum that they will select him, if they are in position to do so. This is one of the draft’s side games – a player has no choice but to go wherever he’s picked, but he can influence where he goes by being selective before draft night. “It sounds like to me he’s getting a guarantee,” says Anstey, who received a guarantee from Chicago with the last pick in the first round (which he ultimately didn't need).

“When I got drafted, I knew being a one-on-one player wasn’t a strength. That’s what a lot of these workouts with different clubs look like. I steered clear of that.

“What he’s doing is smart. There’s conversation around him being a top-three pick, and if that’s the case, you almost shelter him from as much as you can.”

********

SHOULD THE MOCK DRAFTS play out as forecast in late June, expect the first set of headlines in Australia about Dante Exum to fixate on one thing: the money. In an instant, he will become one of the 15 richest sportsmen in the country. The fifth pick is guaranteed a first-year salary of about $3.5 million, with another three years after that worth a total $12 million. A No.1 pick, such as the Melbourne-born American Kyrie Irving in 2011, starts on $5 million, and collects another $17 million.

If this sounds excessive, bear in mind the NBA suppresses the salaries of players in their first four years. Once players become free to negotiate their contract in their fifth season, the numbers really get obscene – this is the territory of five-year deals worth upwards of $20 million a season.

There’s a tendency to view drafting players like picking stocks, as each club tries to build a portfolio of blue-chip shares. But the analogy doesn’t quite hold – the success or failure of a draft pick is often not about whether the judgment of innate talent was correct, but how that talent is cultivated by the team. A great example is Mills, who had the fortune, and took advantage of it, to land with San Antonio, widely admired as the best organisation in the league for player development.

Anstey, who lasted three seasons in the NBA, calls it the biggest difference between the culture of Australian and American basketball. In a shallower talent pool, you tend to take care of what you have. “Players over there to a large extent are commodities,” he says. “For me, you don’t have as much support from team-mates and staff because they know if you don’t do well, they’ll bring someone else in.

It's the fate of top draft picks to go to bad teams. Anstey hopes Exum finds a good fit: “Sometimes, by going to a successful team, there’s a greater sense of security in the playing group and they can take the time to make sure the kid coming in is not expected to be a superstar from day one. I saw how hard it was for Dirk Nowitzki early on; he didn’t set the world on fire when he stepped into Dallas – it took him a good year and a half. Steve Nash had high expectations placed on him. I’ll never forget 15,000 home fans booing him every time he touched the ball because he was struggling.”

On solely a physical level, Exum will need time. His development will be of critical interest to Australian basketball, as the national team forms around a new core. To the delight of the program, Exum has stated his commitment to the Boomers, who head to the FIBA Worlds in Spain in September. Exum was in the line-up during Oceania qualifying against New Zealand last year.

Just as it will be in the NBA, Exum was joining a team full of experienced pros. They had heard about his physical skills – it was how he carried himself off the court that earned raves. He roomed with veteran Joe Ingles (yet another Lake Ginninderra kid), and soaked up knowledge from the dual Olympian. Boomers coach Andrej Lemanis was impressed at how grounded this much-hyped young man was. “He came in and understood how to fit into a team environment. He was respectful to the older guys, listened, didn’t put himself above anybody. And one of the interesting things about that is when you say that about somebody, you often think they’re not a competitor. Yet when he got onto the court,” Lemanis chuckles, “he tried to kick everybody’s arse.”

Lemanis recently went on a trip around the US to touch base with Exum as well as other Australian players based there. “He is mature for his age. But there are times when he’s still an 18-year-old kid, as he should be. When I was in LA, he was excited about going to Knott’s Berry Farm on his day off.”

When this year's big board is filled with names, Exum won't have to wait too long. Photo by Getty Images.

When this year's big board is filled with names, Exum won't have to wait too long. Photo by Getty Images.The question of character always looms large at draft time. Every team swears that they’re looking for “high character”, which is something of a code word. It implies positive traits, but the league isn’t looking for “nice”. A high-character guy is good, or as good as a guy can be, when he’s also a cutthroat competitor.

It's the kind of character that drives players to keep improving. While watching him develop at the AIS, Ian Stacker thought Exum had reaped the biggest benefit from being the son of a former pro – that he understood the level of commitment was day-to-day. Denley agrees: “The amazing thing I saw during my time with him was a lack of ego. I call it a cool confidence – he knew he could play, but afterwards was all smiles. I’ll be interested to see how he’ll survive in the NBA with that attitude.”

In the NBA draft, players are chosen for what they might become rather than what they are. Basketball is one of the sports where the signs of potential can be spotted at a really young age, but how a player turns out often hinges on mentality as much as ability. For Dante Exum, that might be the most important factor of all.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open