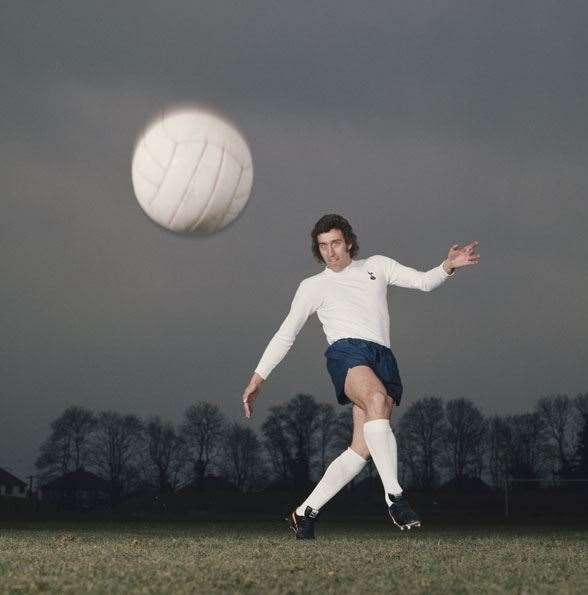

Whatever the code, the modern football is a marvel of science and technology.

WHERE WOULD MODERN TEAM SPORT be without a lightweight, inflatable, spherical, ovoid or prolate spheroid object to boot through or over sticks, into nets, or toss or kick man-to-man? In most cases, it would have been impossible to develop those sports at all.

As they evolved, improvements in the weight, aerodynamics and durability of the ball enabled special features that might not otherwise have been possible.

Some of the early advances in the search for an adequate object for teams to focus on and chase around were gruesome. Early Egyptians often bent it like Beckham with the heads of enemies.

But people always had the urge to kick or throw objects for fun. South American Indians, known for their ingenuity, managed to fashion a lightweight, elasticised ball even before the days of rubber. The Chinese were getting the right idea, using animal skin balls for a game called tsu chu, in which the ball was kicked into a net stretched between two poles.

The notion of a light, safe, soft, inflatable and round object first took hold in medieval Europe, when the bladders of pigs, killed for food, would be kept, dried, blown up and feature in a game in which the participants would keep the object in the air using hands and feet. They’d eventually cover the bladder with leather so it would retain something of its shape. They were on the right track.

By the mid-19th Century we were all taking it for granted that any sport needs uniformity – of rules, playing fields, playing gear and of course the size and shape of the object itself. But a standardised ball wasn’t possible until Charles Goodyear, of tyre fame, patented vulcanised rubber in 1836.

Vulcanised rubber had a profound impact on humanity. The process of vulcanising involves adding sulphur to rubber to fortify it. This enabled the production of tyres, gaskets, transmission belts, seals, shoes and hockey pucks by making the rubber more stable, heat resistant and durable while retaining its elasticity. The rubber ball, designed by Goodyear in 1855, eliminated the element of unpredictability caused by irregular-shaped balls.

However, it wasn’t until 1862 that the first inflatable bladder for insertion into the ball was developed by H.J. Lindon, who, legend has it, invented the India rubber version after his wife died of lung disease from blowing up infected pig bladders; the Lindons were involved in the manufacture of early rugby balls using the pig bladders. Because India rubber was far too tough to inflate by mouth, Lindon developed a brass pump, based on the design of a syringe.

One year later, when the rules of the game of Association Football were drawn up, there was no description of the dimensions of the ball, but in 1872, the measurements that still largely apply today were made possible by the inflatable bladder and the use of vulcanised rubber.

The first inflatable ball for a match was used in the USA, of all places, in a soccer match between Oneida Football Club and a grammar school from Boston. By 1888, the year the English Football League was formed, mass production was possible.

The further development of the inflatable ball was made possible when Mitre and Thomlinson’s, a Glasgow company, discovered that the secret of shape-retention was in the strength of the leather and the skill of the cutters and stretchers. For high-level sport, the outer cover of the ball was made from the rump of the cow, while lower-grade balls were mass-produced using leather from the shoulder. Further perfecting the elusive “roundness” of the soccer ball was the development of interlocking leather panels, which replaced the eight sections that tapered and met at the top and bottom of the ball, much in the way modern rugby balls are designed.

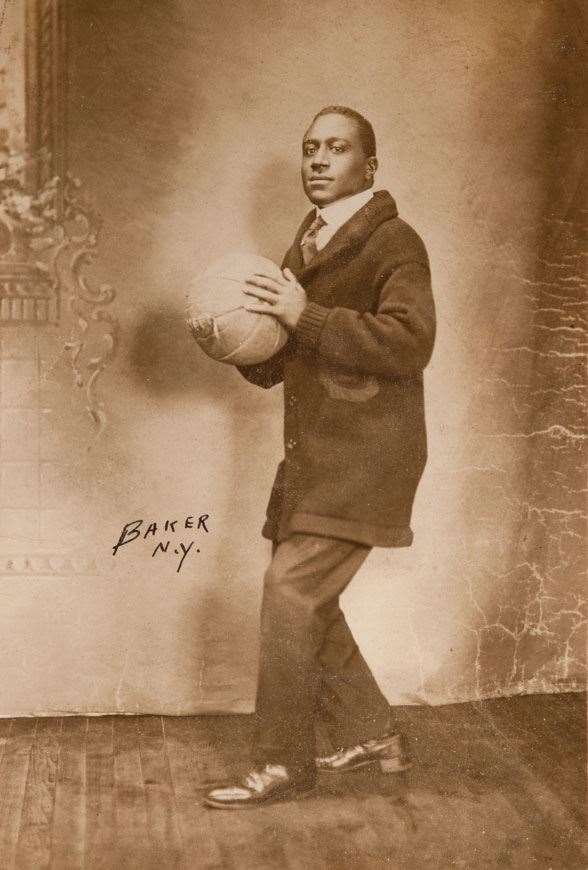

Of course, as the design of a ball developed, its behaviour altered as well. By the 1900s, the bladders became even stronger as rubber technology advanced, and they bounced higher. The versatility of the soccer ball led another of our innovators, James Naismith, to find another use for it, and basketball was invented.

However, the ball was still far from perfect.

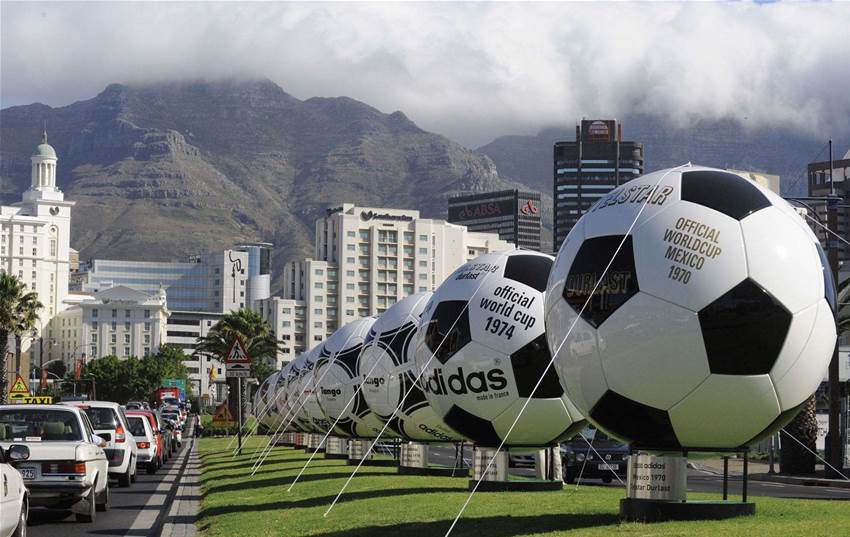

Although there is a certain romance around anything hand-crafted these days, the old soccer ball was hard work. Their shape and condition varied so much from country to country, it’s believed it determined the outcome of the first World Cup Final, when Argentina were allowed to use the sort of ball they were used to in the first half, Uruguay theirs in the second half. Sure enough, Argentina won the first half and lost the second – and the match.

A few further developments were significant in the evolution of the ball. Firstly, in the 1940s, a frame, or carcass, was inserted between the bladder and the outer casing to prevent loss of shape. One other factor in the retention of shape was water absorption. This was dealt with by coating balls with synthetic material. The unwieldy lace slit which enabled access to the bladder was replaced with a valve.

The completely synthetic ball was first produced in the early 1960s, but synthetic “leather”, to further address the ongoing problem of absorption, didn’t come into use for top-level games until the 1980s. The ball now imitated the qualities of leather, which, it was still felt, provided the best result.

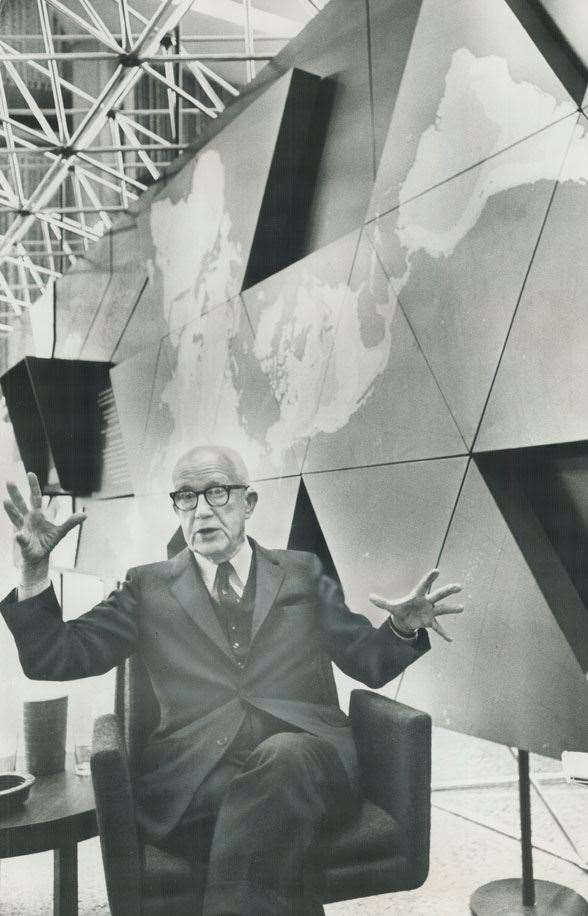

Today’s synthetic ball was the result of a left-field incursion by Buckminster Fuller, author, inventor, systems theorist, architect – all-round ace, basically. Bucky, perhaps inspired by another of his inventions, the geodesic dome, developed the model which was used in the 1970 World Cup: 20 hexagonal and 12 pentagonal pieces fitted and stitched together to form a sphere. The black spots designed into it helped players learn how to track and master its swerve.

Fuller fans might think it an amusing co-incidence that Bucky also developed a simulation game designed to solve the world’s problems, called The World Game. His brief flirtation with the other world game changed it forever, and became the basis for mass-produced soccer balls of today.