Was the Floyd Mayweather vs Manny Pacquiao superfight too late for boxing?

George Foreman once said, in his late-career grill-salesman guise, that he grew up in such poverty that his family “couldn’t afford the ‘o’ or the ‘r’. We were po’.” Lean circumstances make the boxer; indeed, it’s out of the ordinary when you find one verged on a lower-middle-class upbringing. It’s such a prerequisite, it could be written into the tale of the tape: height, weight, reach, level of hardship overcome in life.

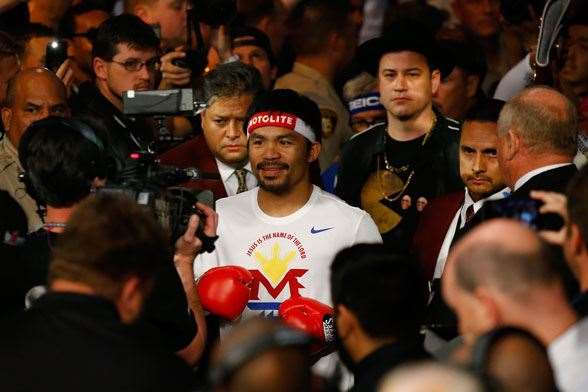

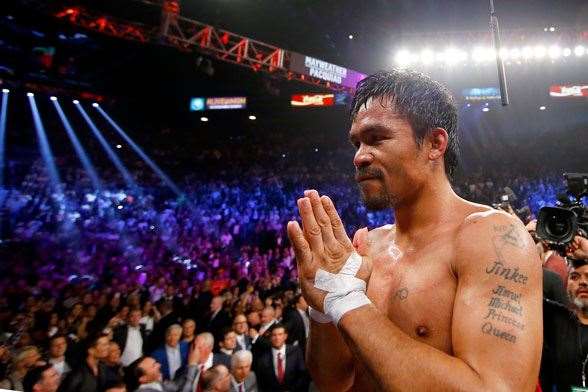

Twas ever thus. Boxing as ladder out of poverty, a story as old as the sport itself. And even on the lowest, barest rungs where boxers come from, it’s hard to comprehend the origins of a Manny Pacquiao. Five years ago, while mulling a profile for the magazine as the Pacquiao phenomenon had its global breakout moment, I caught up with Filipino sports commentator Chino Trinidad. To call Trinidad a veteran Manny-watcher is an understatement. He used to do commentary for Blow By Blow, a local boxing TV program in the 1990s that resembled scenes from the first act from Rocky. It was the place where a teenaged and more reckless Pacquiao first made his name as a crowd-pleaser, winning all-action flyweight slugfests in dingy venues across the archipelago. “One time he fought in an old basketball court in Cotabato where you had half the stadium with a roof, the other half blown away in a typhoon,” Trinidad recalls. “We went to the worst, and I mean worst places to put up a fight. From cockpit arena to the MGM Grand – that’s how this journey is.”

Here was a pug who fought like his livelihood depended on it, because it did. The details of Pacquiao’s hardscrabble youth in General Santos City, an out-of-the-way place even by the out-of-the-way standards of the Philippines, are well-established. Father absent, young Manny lived in the streets, hawking donuts from a bicycle. He turned to boxing to support his mother and five siblings.

“He had hardly any money on him,” Trinidad continues. “He had to take four jeepney rides to be able to go to training. You know one thing: Pacquiao can go hungry and he wouldn’t beg for a single centavo.”

Trinidad brings up Pacquiao’s eighth professional bout, held in Palawan. A needle of an island that lies north of Borneo, it’s even further off the beaten paths of the Philippines, except if you’re into scuba diving. Trinidad notes that Pacquiao’s opponent in that 1995 fight, Renato Mendones, eventually became a bank robber, part of a notorious outfit known as the FX Gang. Mendones met his end in a shoot-out with police, who had trapped the gang in a set-up.

Trinidad’s TV crew had to bring its equipment by boat. “The boat ran aground, so we had to take the heavy TV equipment and load it into smaller boats, the paddle boats to bring it to shore. That took eight hours extra, so I ordered food for my crew.

“It was after weigh-in. Pacquiao was there; I knew he was hungry, I could see it. One of his guys sat down and started eating. I didn’t invite him. This is a no-no; that’s being damn rude. Pacquiao was there at the other end [of the table]. He never touched the food until I told him. And to this day, he hasn’t forgotten.”

For Trinidad, it was this hunger, or the mastery of it, that explained Manny Pacquiao. “There is no school in the world that will teach you toughness like going hungry. But this guy made it through, because he is not made of ordinary stuff.”

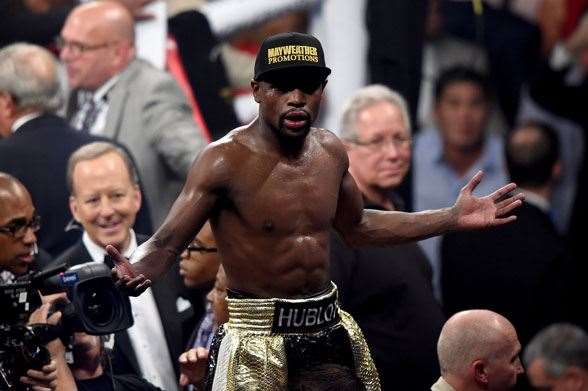

Going hungry has long ceased to be a problem for Pacquiao. Floyd Mayweather has known similarly tough times, suffering through a fractious relationship with an incarcerated father, living seven to a room and being surrounded by the worst of the drug trade. As he likes to point out, he now has closets in his Las Vegas home that are bigger than the places he grew up. When they face each other in May – finally – the juxtaposition with their humble backgrounds will be glaring. They will make boxing’s richest fight ever.

The money associated with Mayweather-vs-Pacquiao induces its own kind of hook-to-the-head daze. It is near guaranteed to break the pay-per-view record of 2.4 million buys, set by another Mayweather fight, against Oscar De La Hoya in 2007, and with an expected price of $100, could generate around US$300m in PPV money. Tickets basically didn’t go on sale; block reservations of the 16,800-capacity MGM Grand arena sent prices skyrocketing to US$1500 for the cheapest seat in the house, and the taking from the gate was expected to exceed US$70m, more than three times the previous record. Factor in outside-US television rights and sponsorships (Mexican beer brand Tecate kicked in almost $6m) and revenue for the fight might reach US$500m.

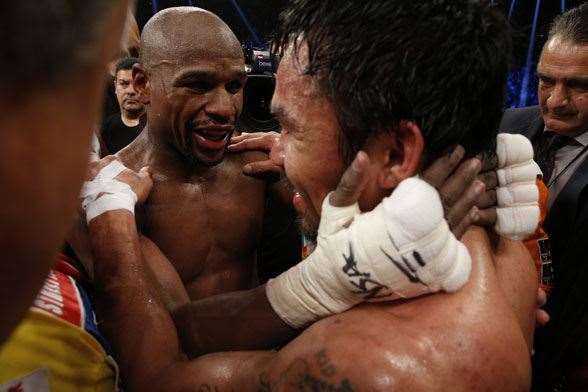

Half a billion for a one-night-only, non- recurring sporting event. Such figures have become an inescapable feature of Mayweather-Pacquiao. But while it’s hard to see past it, this fight isn’t about the money – or isn’t only about it. No amount of sideshow can distract from this match’s genuine importance in the context of boxing history. Over the course of its storied past, it’s been exceedingly rare that the two best fighters of any given era have enough overlap, be it in weight class or prime years, to settle the ultimate question in the ring. By their own merits, Mayweather and Pacquiao are all-timers: the still-undefeated Floyd is probably the greatest defensive fighter to put on gloves, while Manny, a holder of titles in eight different weight divisions, rates as the best little man in boxing history. They have both held in recent times the mantle of best pound-for-pound fighter. They could have never met, and these legacies would remain assured.

And for the longest time, it appeared that they would never meet. “Mayweather-Pacquiao” became code for a shoulda-been, something that made sense yet was rendered near-impossible by the byzantine internal politics of boxing. It was a sport, so troubled in its contemporary state, showing its worst side.

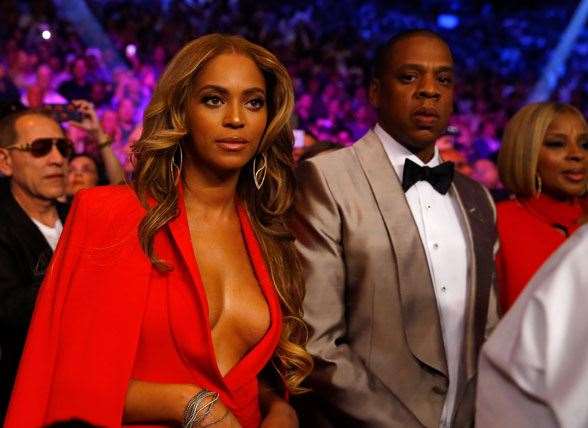

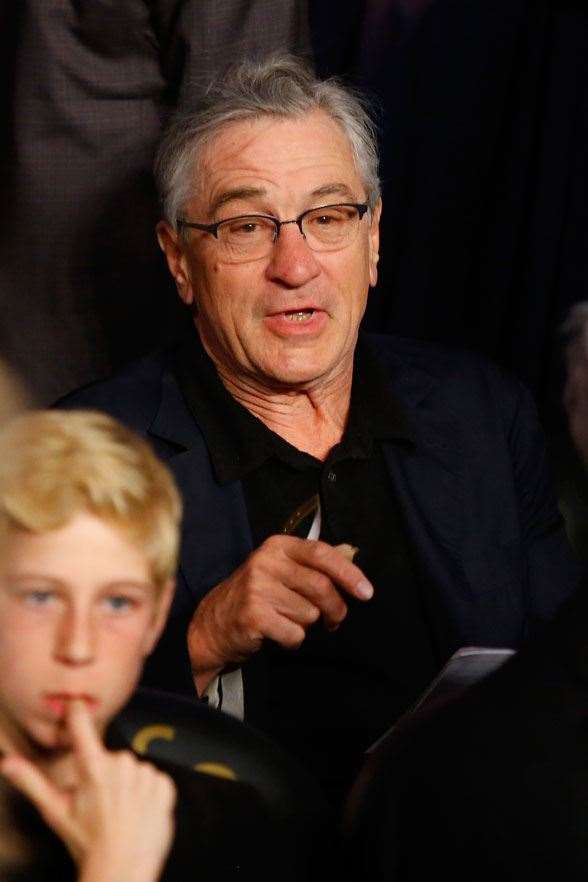

But this troubled sport has somehow contrived to deliver its super-fight, the fistic landmark of this time that will be mentioned whenever people talk of the great ring encounters. Among sports fans, it has revived a race memory for when the marquee billings of Ali-Frazier, or the four-sided combinations of Leonard-Hearns-Duran-Hagler were the definition of appointment viewing. For the increasingly niche fandom of boxing, it has been neat to witness the sport’s re-connection to the wider public consciousness. Even the non-fans, including the portion that might be repulsed by boxing, will be taken in by the allure of the spectacle.

Contained within Mayweather-Pacquiao, though, is a dilemma. At once, it speaks to the lingering relevance that boxing has to the culture, yet also highlights how the once-sweet science has marginalised itself. The two fighters aren’t the only ones with a lot riding on the outcome of this contest – their sport’s reputation is riding with them. The last thing Chino Trinidad said during our conversation was a sentiment often heard among fight fans over recent years: “I would love to see him fight Mayweather ... For the sake of boxing.”

******

Maybe it is just about the money. Or to put it precisely, how it can be made in boxing. Last January, Floyd Mayweather was scheduled to visit our shores for the first time. Not to box, mind you – Mayweather hasn’t left Vegas to fight in ten years, which is another of boxing’s issues. He was coming here in entrepreneur mode, making gala dinner and nightclub appearances in Melbourne and Sydney. His rock star-like list of demands made headlines: entire hotel floors booked out for his 31-strong entourage, unlimited supplies of gummy bears and M&Ms, an on-call butler, chef, make-up artist and barber with experience in cutting African-American hair, even though he’s bald.

The immigration department scotched Mayweather’s plans, denying him a visa on character grounds. It wasn’t unexpected. An online petition, signed by 46,000 supporters, had emerged calling for Mayweather to be barred from entering Australia because of his deplorable record of domestic violence abuses, which culminated in him serving a two-month prison sentence in mid-2012.

Our sports-mad nation had seen fit to reject the world’s richest sportsman. What was really interesting, however, was it didn’t cause much of a blip at all, which said a lot about the enigma that is Floyd Mayweather’s stardom. The man’s nickname of choice is Money, and it’s apt – after a one-year hiatus, he again topped the 2014 Forbes list of the world’s richest athletes, pulling in an estimated US$105m. Left in his dollar-strewn wake was a host of brand-name luminaries: Ronaldo (US$80m) and Messi (US$65m), LeBron (US$72m) and Kobe (US$61m), Tiger (US$61m) and Federer (US$56m).

The thing that stands out about the Forbes list is the breakdown of income. Most of the top ten earn a good chunk of change from endorsement: about a third for the football icons, more than half for the basketball high-flyers, and in a classic pattern for the golf-and-tennis soloists, the major share. Then there’s Floyd, who has an endorsement income of $0. All of his $105m is derived from his earning power as a prizefighter.

In one sense, Mayweather has hacked the system of modern sports stardom. He is largely free from the kind of limitations that the high-net-worth athlete has to concern himself (and face it, they’re all men) with. While Woods suffered major hits to his personal image and watched similar damage to his bank balance, Mayweather has piled up transgressions and cash at the same time.

How he’s done it is testament to his business savvy – Mayweather has taken control of his career like few other great boxers have ever done. Instead of being in thrall to some slick, overbearing Don King type, he serves as his own promoter, with his company managing every aspect of the staging of his fights (in that light, his list of demands for his tour doesn’t seem so out of character). As with any get-rich success story, he’s been the beneficiary of fortunate timing – his marquee appeal rests on the fact that he’s the only great American fighter going, which has allowed him to reap the bounty of the US pay-per-view TV market. And unlike Pacquiao, who has to give a cut of every paycheque to promoter Bob Arum, what Floyd gets from a fight he keeps.

Boxing has a long and sorry record of exploiting fighters. That Mayweather has defied that convention is deserving of some credit, but the power he’s gained has been used primarily to enrich himself. No one would accuse him of serving his sport’s best interests. To be fair, it’s near-impossible to find a powerful figure in boxing that does. As the rest of pro sports has marched the path of becoming more corporate, boxing proudly remains a free market, in the way that a wildly disorganised bazaar is a free market. What passes for structure in boxing is a patchwork contraption that allows certain stakeholders to protect their money-making turf. Explanations for boxing’s mainstream decline commonly raise two factors: the confusion over champions thanks to the mess of sanctioning organisations, and the staple diet of pay-per-view events walling the sport off from casual viewers. As UFC boss and lifelong boxing fan Dana White says, there are many simple fixes in boxing if there was some kind of centralised control looking out for the bigger picture. But there is none, and the tortuous path to Mayweather-Pacquiao is the perfect illustration of it.

The fight first appeared a realistic possibility in late 2009. While already a name among ring aficionados for his epics against the Mexican champs in the featherweight and super feather class, Pacquiao’s stardom really exploded over a 12-month stretch when he stopped Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton and Miguel Cotto. Mayweather had retired after sweeping away De La Hoya and Hatton in ’07, making a brief dalliance with WWE wrestling before returning to boxing. His disposal of Juan Manuel Marquez, a once and future Pacquiao nemesis, was very sharp for a guy who had not fought for 21 months.

The match was a natural. The terms appeared settled in December for a fight the following March, then the saga of the drug-testing program began. Both fighters had agreed to random Olympic-style testing, a tougher standard than what had been previously used in boxing; the first breakdown occurred over the Mayweather camp’s insistence that Pacquiao be subject to random blood testing up until fight time, conducted by the American agency USADA. Pacquiao’s promoter, Arum, accused the other side of shifting the goalposts, making an issue of the blood-testing window out of harassment. Pacquiao offered a 24-day cut-off before the fight, while Mayweather countered with 14. The fight was off.

There was a subcurrent running through this: Mayweather and his team had loudly hinted at how a man as small as Pacquiao could generate such punching power, even as he moved up in weight. This led to a defamation lawsuit from Pacquiao, which would eventually be settled out of court, with Mayweather paying a seven-figure sum. Both went on to fight other opponents in the first half of 2010, and any chance of it happening later was off after Mayweather chose not to fight the rest of the year.

A phony war of we-want-it-they-don’t ensued throughout 2011. Pacquiao budged on the drug testing; Mayweather started talking about the purse split, once 50-50, tilting in his favour. This was a sticking point for Floyd, who has prided himself on receiving the more favourable terms in his fights. This was destined to lead to problems – his relationship with Arum, who was once Floyd’s promoter, was notoriously bad.

Making the problem even worse was the Cold War-like division in boxing. On one side, there was Arum’s company, Top Rank. On the other, there was Golden Boy, which started life as Oscar De La Hoya’s vehicle but had evolved into Mayweather’s co-promoter, run by boss Richard Schaefer and guided by Mayweather adviser Al Haymon. Arum and Schaefer were known to loathe each other, although rivalries among promoters usually haven’t stopped big fights from happening, particularly with the money to be made. But Top Rank and Golden Boy had divvied up boxing altogether neatly, with their own stables of fighters, sets of sponsors, preferred venues and favourable sanctioning bodies. The final piece of this stalemate slid into place when Mayweather dropped cable TV network HBO as the broadcaster of his fights, bolting for an eye-popping six-fight deal with Showtime that would guarantee him a minimum payday of $200m. In response, HBO ended its ongoing relationship with all Golden Boy fighters, and threw in its lot with Top Rank. Schaefer promptly moved his fights over to Showtime, where it wasn’t lost on anybody that its top sports executive had previously been Golden Boy’s legal counsel.

With these self-contained ecosystems now backed by TV, the twain didn’t need to meet, ruling out a host of potential matches that boxing fans wanted to see. Especially the biggest one of all – Mayweather’s prison term disrupted any good chance of the fight happening in 2012, but it was Pacquiao’s horror year that proved problematic. After his egregious robbery of a loss to Timothy Bradley in June, Pacquiao was knocked cold in December by Juan Manuel Marquez’ right hand, and seemingly the prospects of a mega-fight with it.

******

Almost 12 months on, in late 2013, I travelled to Macau to watch Pacquiao’s comeback fight, against Brandon Rios. Bringing the fight to Asia represented a significant gambit for Bob Arum, and the event carried all manner of cultural freight: a bold play for new audiences, a recognition of the region’s rising economic power, a break from the usual big-fight orbit even if it was a rather deliberate effort to replicate Vegas in China.

It had another bit of Vegas feel to it – the fading, once-famous act playing out the string. There had been genuine concern in the lead-up that Pacquiao couldn’t be the same after such a brutal loss, and it looked like he had opted to make his return in a safe place far removed from the eyes of the US media. But he whipped the tough Rios handily, and the decidedly pro-Pacquiao crowd was relieved as much as excited.

I took away two distinct impressions from the event, quite contrasting. First was the scores of Filipinos who had come to the fight, not from the Philippines but from across Asia and the Middle East. These were the overseas Filipino workers, the more than two million who leave home to do the grunt work of globalisation and send back the remittances that account for a staggering ten-plus percent of the Philippine economy. While the mania for Pac-man has cooled somewhat in the islands, particularly since he entered politics, he remains the idol of the OFW – the ultimate example of the Filipino who went out into the world, and made a fortune by dint of his own two hands. Boxing was one of the few avenues where he could have achieved this.

The second impression had less to do with Pacquiao. The morning after the fight, at breakfast, I almost stumbled into a restaurant booth where a sleeping body lay, face bruised and battered. It was the Australian fighter Billy Dib, who had lost by knockout on the undercard. While his dozen-strong entourage ate a few tables down, Dib was prone with an exhaustion that seemed beyond human limits.

It was a sobering reminder, and one we don’t often care to see post-fight, of boxing’s savage nature.

These contrasting faces of the fight game sum up the moral quandary that boxing faces these days. It remains one of the few truly universal sports, but its time-honoured ways seem out of step. Under siege from the likes of the UFC on one side, and a rather assertive ideal of civility on the other, there’s a palpable feeling that we’re watching a grand old sport retrench before our eyes. In its glitz, Mayweather-Pacquiao may have the look and feel of a revival, but instead may be a raucous wake.

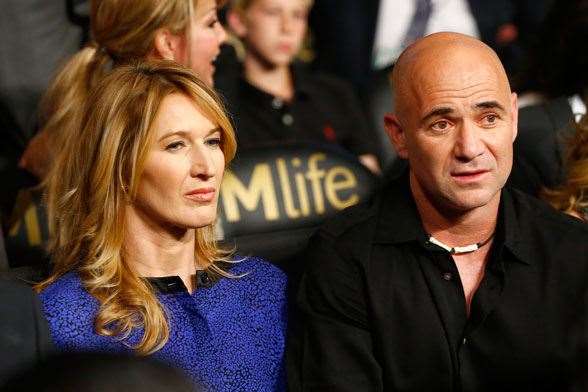

At the sole pre-fight press conference in Los Angeles, the atmosphere was strangely subdued, both by boxing’s carny-like standards and the past acrimony between the two sides. But as ESPN commentator Brian Campbell noted, it rather felt like boxing’s dysfunctional family finally getting together for the big reunion gathering, not particularly wanting to be around each other, but present out of some vague fealty to what had come before them.

That’s probably the nicest explanation you could make for why this fight ultimately got done. After all the contentious negotiations, it ended up with USADA conducting the drug tests and Mayweather getting a 60 percent cut of the purse. As haphazard as the entire process appeared – exemplified by the two fighters’ chance meeting at a NBA game in Miami in January, where they swapped mobile numbers – they were pushed back to the table because the supply of viable opponents really had run dry. Their pay-per-view numbers in 2014 were soft, with pressure brought to bear on Mayweather only halfway through his Showtime deal, while Pacquiao had to resort to a Macau trip again. To underline how important TV was to the process, the critical figure in the negotiations turned out to be Les Moonves, the boss of American network CBS, which also owns Showtime. Unsurprisingly, Moonves is a boxing fan.

Other conditions have helped. The promotional Cold War has thawed, as De La Hoya took back control at Golden Boy, forcing out Schaefer and reaching across the lines, such as bringing Mexican middleweight star Canelo Alvarez to HBO. Possibilities are sprouting across the boxing landscape, none more interesting than Al Haymon’s latest play.

Haymon is boxing’s current figure of intrigue. Like Don King, he hails from Cleveland, but this Harvard-educated former concert promoter is the anti-King – he doesn’t do interviews, and generally avoids appearing in public altogether. But as adviser to Mayweather as well as a host of other top fighters, he wields powerful influence on what fights get made. Backed by private equity, Haymon set up a deal to bring boxing back to free or basic-cable television, paying $20m to NBC to buy airtime for 20 shows across the broadcast network and its pay offshoot. He subsequently spread his Premier Boxing Champions brand to other channels.

While the biggest bouts will remain pay-per-view events, the basic idea is to get boxing’s potential stars wider exposure. It distinctly resembles the strategy of the UFC, which has a range of programming on different outlets, seeding lesser-demand cards on free or niche channels and reserving its top-line events for PPV. There’s interest in seeing if boxing can work on TV again – even Nine is entering the fray, airing its first title fight in a quarter of a century on May 1, after a rugby league Test. The featured fighter, incidentally, is Billy Dib, taking on Takashi Miura in Tokyo.

Perhaps the most fervent hope of all for boxing is that Mayweather and Pacquiao, with the eyes of the world upon them, produce a classic. It’s probably advisable to temper expectations. English author Matthew Bazell, whose recent book The Greatest Fights That Never Were was published before the fight was confirmed, notes that Mayweather-Pacquiao is already lost to us in one regard – nothing will quite match the possibilities if the two had met five years ago, closer to their peak form.

On the other hand, boxing history has shown that two great fighters, even when past their primes, can still give us something for all time. Any Filipino of a certain vintage, who can remember back 40 years ago, will tell you that. While living in the Philippines about 20 years ago, I went with my dad to a place called Ali Mall, which happened to be the first multi-level shopping centre built in the country, in 1976. Where the name came from was obvious – it’s located next to Araneta Coliseum, where Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier fought.

The mall was exhibiting a small selection of photos from and around the fight that Dad, an Ali fan from way back, wanted to see. It was right there in the pictures, the scenes of existential strain that became legend. Thrills weren’t expected when the old rivals met in Manila. Famously during the mid-rounds, Ali, in his archetypal Ali guise, said to his surging opponent that someone had forgotten to tell Frazier that he was washed up. We can only hope that same reminder is given to Mayweather and Pacquiao, and maybe all of boxing, too.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open