FEATURE: Aussie cricket's man of the moment.

IT'S THAT THIRD INITIAL, the second middle name, you see. Cricketers fairly end up with the most famous sets of initials in the country, thanks to an age-old scorecard protocol that operated with a dignified formality. We know our DG Bradman and SK Warne, and even the slight misdirection of a KD Walters. But it’s those three-letter guys, with their mellifluous-sounding, triple-barrelled designations, and the fun that happens in the far reaches of the second middle name. MEK Hussey was the ever-dependable Mike, the stolid Mr Cricket, but the “K” stood for Killeen. The appropriately named SCG MacGill, well-known for his inclination to refined tastes, had the vaguely exotic, Welsh-origin, no-vowel moniker of Glyndwr.

So, how about it, SPD Smith? Steven Peter Devereux? Smith, all blond spikes, steely blue gaze and youthful visage you wonder if he’ll ever outgrow, cracks a smile. “I think it was my dad’s,” he says. “Or mum’s ... I’m not sure. I should probably ask. Somewhere down the tree.”

The “Peter” comes right from Dad, who explains that Devereux was his grandfather’s name, or at least the name he used. “Everyone knew him as Dev,” says Peter Smith. “It’s in the Smith line, if you like. Everyone except me has it. My brother does, my father does and Steven does. It’s something that’s gone through for quite some time, and no idea exactly where it came from.”

Getting slapped with a hard-to-explain label is something Steve Smith has become accustomed to. Sitting in the lobby of a swank Sydney hotel, in camp with the Australian side ahead of yet another tour of duty, he occupies a comfortable position in an elite circle. The cricketers had been hanging with the Wallabies the night before, as the rugby union boys prepared to meet the All Blacks later that week. Police were surrounding the block in preparation for the arrival of former US presidential candidate John Forbes Kerry, another guy with an interesting set of initials considering the job he was seeking. The entire atmosphere seemed to reflect the bullish mood of Australian cricket, restored over the last ten months to five-star, top-of-the-line status. And one of the men who got them there surely was Steve Smith.

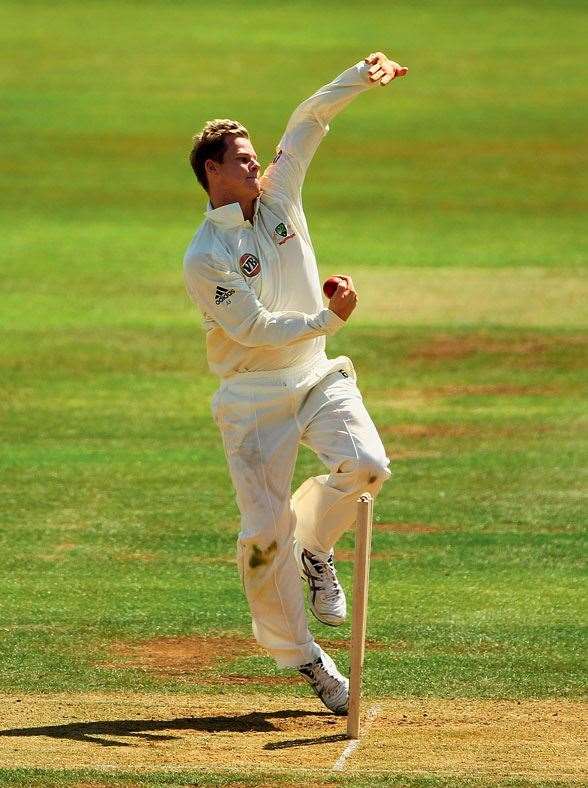

In retrospect, this scenario wasn’t hard to believe. From his emergence on the scene of Sydney grade cricket as a young teenager, Smith was instantly tabbed as a future star. He was one of those precocious all-round talents, molten cricketing gold that could be poured into any kind of mould and shaped according to whatever the nation needed. There would be a fast track, there would be baggy greens and day-night pyjamas, there would be impact with bat, ball or in the field. There were immediate comparisons, and they were lofty: the next Warne? A new Benaud, maybe?

As always seems to happen with sporting careers, the reality turned out to be less smooth and more interesting. Ask Smith to reflect on those early expectations and he responds with a thoughtful pause. Israel Folau, a man who similarly has had to live with people trying to define and harness his own athletic gift to their ends, has just wandered by to say hello. Smith is measured: “I think you’ve got to have the people around you that you can trust and listen to, and know that they’re trying to get the best out of you. The people from the outside might have a different idea, and you can listen to that. But you’ve got to have, in your mind, a clear idea of what you want to achieve.

“When I first played Test cricket, I was still a bit young and probably immature. I hadn’t quite grown as a cricketer as much as I would’ve liked to when I first started playing. Of course, I’d never say no to an Australia call-up. But at that time, I wasn’t quite ready to play the way I am now.”

******

THE THING THAT STRIKES about Steve Smith is the self-assuredness. The good kind, too, the one the sports shrinks are always talking about – not loud or brash, but matter-of-fact, that bedrock confidence that fuels athletes. Cricket, after all, is what Smith set out to do. In his last year at Menai High in Sydney’s Sutherland shire, he had a meeting with the school principal, a Cricket NSW welfare officer and his club coach, Trent Woodhill. Smith wanted to leave school early to pursue an opportunity to play in England, a decision that had the support of Woodhill, who predicted Smith was going to be a professional cricketer. The Cricket NSW representative urged him to finish his education, but funnily enough, the principal agreed with Smith.

“I’d missed quite a bit of school through playing under-17s and -19s, so my attendance wasn’t great,” Smith recalls. “It was all I ever wanted to do. That was my sole focus, cricket. All my friends used to spend their weekends at the beach, hanging out with each other. I’d always be: Saturday playing cricket, Sunday playing cricket, the whole weekend gone. That was the sacrifice that I was willing to give up because I wanted it that bad.”

The shire was fertile ground. Smith’s upbringing in the game sounds almost idyllic. Dad Peter worked from home in his son’s early years, so he was able to take his only boy (he has an older sister) to the nearby local park every afternoon. The elder Smith, who describes himself as a better coach than player, would bowl a bit of everything. “It started off when he was ten and then worked through until he got older,” Peter says. “I worked my way further and further up to bowl quicker at him, so at one stage I was bowling three paces in front of the popping crease.

“There was another little game we played in the backyard. We had a small backyard, so he used an old bat that we cut down. We used a soft ball which we’d flick out, and you could spin it both ways, so he had to watch the hand very carefully. Surrounding him were gardens, and any ball he hit in the air into the gardens was out. There was variation, which gave you footwork, made sure you watch the ball. Again, he got very good – I couldn’t get him out in the end.”

Smith became the golden boy of Sutherland District CC, zipping through the lower levels and cracking grade at 15 years old. It was a high-quality outfit – Phil Jaques was a fixture, and English quick Tim Bresnan was also there at the time. Glenn McGrath, who has his name on the club’s oval, would show up periodically. “We’d heard little bits about Steve coming through, that he was a talented leg-spinner-batter,” Jaques says.

“He had some ability with the ball in hand, and we thought that might end up being where his opportunities lay. He’s always had the love for batting, and wanted to be a batsman. He looked a bit ungainly, wasn’t the normal technician you see in young players who make it to the top – they’re generally pretty easy on the eye. Steve was a bit unorthodox, and went about things differently. But mentally, the way he approached his cricket was far superior to his years, really.”

His feats in grade were prodigious. On debut he scored 90, then a ton a few matches later. The story everyone tells is the match against Mosman in 2010 in which Smith came to the crease after Jaques was dismissed in the first over, his team 190 runs behind. Smith hit nine sixes and 15 fours over the next 80 minutes, including the highlight – on a no-ball free-hit, Smith switched to left-handed, and proceeded to hit the next delivery over the deep backward square boundary. His first-class debut, for NSW, came at 18. Such big-bang, full-spectrum ability put Smith right in the frame of the shorter formats, but his potential as a leg-spinner also intrigued the overseers of the Test side. Smith had always identified himself as a batsman who bowled, but now found his path to the ultimate level dictated by the niftiness of the bonus features rather than the quality of the main function. Like Cameron White, another similarly talented player shoehorned into a role with the ball as selectors grasped at what became a dozen different options in the era post-Warne, the range of Smith’s skills were doing him a disservice.

The too-soon introduction to Test cricket, in 2010, coincided with the supernova-like end stages of Ricky Ponting’s tenure as captain. Smith debuted against Pakistan at Lord’s, and made it back into the XI by the middle of the Ashes series that Australian summer. The English media made much of the notion that Smith had been brought into a struggling side to provide some levity – he was there “for his jokes”. That the Aussies won that Perth Test is often forgotten, as England subsequently romped to a pair of innings victories in the next two and a dominant 3-1 result. Smith was the last man left in the middle in Sydney, posting a rearguard half-century; he also hadn’t taken a single wicket against England. Smith wasn’t chosen for the following tour of Sri Lanka, with chairman of selectors Andrew Hilditch admitting Smith’s omission was harsh. Harsher still was the rationale: “We didn’t think he’d cemented a spot in the top six batters and we didn’t think he’d cemented a spot as a spinner,” Hilditch said at the time.

******

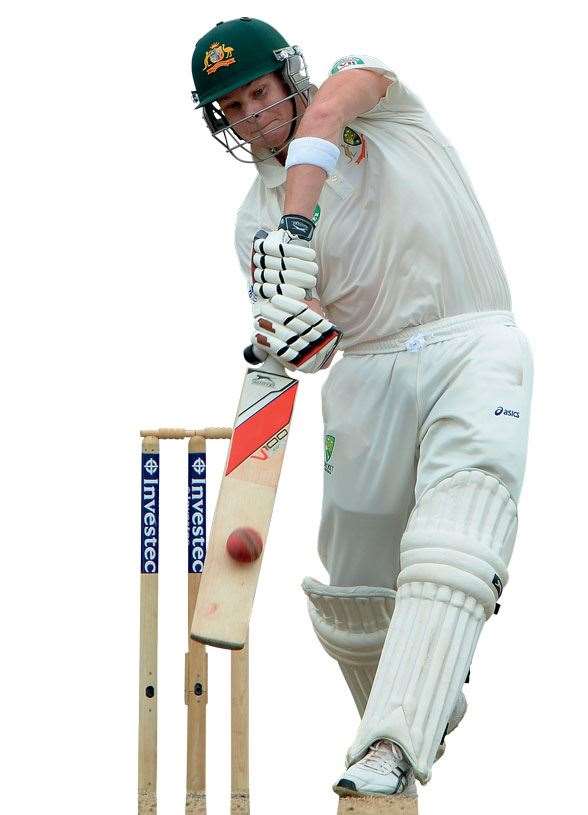

STEVE SMITH'S CALM BEARING in conversation comes as something of a surprise, because it stands in direct contrast to what we see at the crease. He’s known for his fidgeting – all the buzzing about, the arranging and tapping, like he can barely contain the energy he wants to bring to his run-scoring. Where the fidgets come from is as much an unknown to Smith as the Devereux: “That’s still there, all the time ... It just happens.”

Cricket, more so than other games, has a stylistic fixation. It can be downright brutal on things that don’t look right, and the less-than-classic aspects of Smith’s batting became an easily gripped cudgel for critics to whack him with. Combined with his fast-track status, and the general antipathy towards the newly enriched T20 generation of cricketers, there was just enough to dislike about him. “If you look at social media, which is always a good thing to look at for these sorts of things, originally he had a lot of haters,” Peter says. “He did. He was one of those guys who polarised people.”

Woodhill, his junior coach, noted that Smith had fought perceptions all the way up about the way he played. “He’s unorthodox, and Australians hate unorthodox cricketers,” Woodhill told Cricinfo. “If he was an Indian cricketer right now, he’d be untouched, he’d be smoother, he’d be fluent, but in Australian cricket, from a young age people want to talk technique. We want to clone batsmen in Australia. Everyone wanted to bat like Greg Chappell in the 1970s and the 1980s, then everyone wanted to bat like Steve Waugh in the 1990s, then we had the power phase with Matthew Hayden.”

For all of Smith’s unorthodoxy, there was common agreement that he was a thinking cricketer. In fact, he was unorthodox because he would think through his game. There was a pedagogical emphasis to those afternoons at the park – Peter is a scientist by training, so he tends to be analytical when looking at things. And the Smiths’ experiments in the nets focused on the idea of variation, and the ability to respond to it. “That’s why people look at him and say his technique is not perfect,” Peter says. “But it’s adaptable. If everyone has exactly the same technique, then you have a problem, because a bowler knows exactly where to bowl at you.”

It might be the creed of the new-era batsman. Smith has argued for the case that T20 will add to batting technique rather than detract from it. But in making his return to the Australian team, he found that his key to better batting was stillness. “I used to have a bat tap when the bowler was about to bowl. I had to get rid of it because it was making me real high at the crease, not quite as balanced. When I got rid of that, everything felt like it clicked into place. It made me more still at the crease; I was able to play my shots more effectively. Since I got rid of it 18 months ago, everything has headed in the right direction.

“Over the last 12 months I reckon I haven’t premeditated as much as I did before. That may have got me into a bit of trouble. It’s about having a clear mind, seeing the ball and hitting it to wherever I have to. I’ve got enough shots ... you don’t have to premeditate too much to hit those gaps.”

Such adaptability is one of the reasons that Smith is, outside of Michael Clarke, the best player of spin bowling in the country, although he says being able to bowl spin is not quite the advantage one might think when facing it at bat. In any event, it was the widely heard rationale for Smith earning a national recall for the March 2013 tour of India. He found his Test fortunes aligned with another crisis moment – the homework debacle, which ousted another young batter in Usman Khawaja and put Smith in for the last two Tests of the series. And while he performed well, they were in losing efforts, and the Australian team continued to reel. Smith wasn’t named in the initial squad for the Ashes three months later.

A critical career moment arrived in, of all places, Belfast, playing for Australia A against Ireland. On a tough wicket, Smith scored a century, exquisitely timed as Clarke’s back ailment flared up again and David Warner copped a suspension for his nightclub incident. Smith wasn’t aware that the call was coming. “The selectors must have seen something in that innings. It got me to the Ashes.”

The ten-Test epic between Australia and England in 2013-14 was subject to all manner of random influences – the reversal in result from one series to the next was proof of that. But one of the more reliable trends was Smith’s emergence as bona fide Test batsman. He had been warm through the first four matches, but much like the Australians’ overall performance in England, it was vexing – stretches of good play undone by a sudden lapse, or in the formulation of the team in the aftermath, an inability to “win the big moments”. Smith’s big moment arrived in the last match, at The Oval, where he posted his maiden Test century, 138 not out.

“I sat down a Test or two before [the Oval Test] with Michael di Venuto, the batting coach. And I was extremely happy with the way I was hitting the ball in the nets. Everything felt good, everything felt in place. And I was having a chat to him. ‘What’s going on, why aren’t I scoring any runs here?’ And he goes: ‘Mate, you’re not out of form. You’re just out of runs. There’s a difference.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, you’re right.’

“I had the same conversation before the Perth Test, where I got a hundred. I didn’t feel I was out of form, I felt I was hitting the ball as well as I ever had. I just wasn’t getting the runs. But I had the confidence behind me, and it was just a matter of scoring runs. Since I got that score, more in Perth than in The Oval, it gave me the confidence to know it was in me ... Since then it’s seemed a little easier.”

Smith scored another century at the SCG, then another in the opening game of the tour to South Africa. Peter was on hand in Sydney, camera at the ready – photography is his hobby, and has pictures of some of the big moments of his son’s career. His favourite is Steve’s first Test wicket, at Lord’s. “As he was approaching his hundred, I’m sitting there saying, ‘Am I going to get the camera out, or am I going to enjoy the moment?’” Peter said. “Camera, moment, camera, moment. Even got to the point where he was on 99, I put my hand on the camera, but I couldn’t get it. I wanted to enjoy the moment. Lots of people take pictures. Enjoy the moment.”

******

AFTER ALL THE COMPARISONS that have been invoked, it turns out that Steve Smith invites association with another Steve – Waugh. Similarly he was brought into the Test side early as a dynamic all-around talent, endured being dropped, then came back a tighter, more refined player in the number-five spot, no less. In a recent column, New Zealand great Martin Crowe named Smith among a group of four young players, along with Virat Kohli, Joe Root and Kane Williamson, destined to claim the mantle of number-one Test batsman at some point. Crowe notes that each had a single noticeable flaw – correcting it was key to unleashing their obvious talent. About Smith, he wrote: “Initially he seemed anxious ... he now seems comfortable playing home or away, against pace or spin, off the front or back foot.”

Phil Jaques, who endured his own star-crossed circumstances during his Test career, says Smith’s time out of the side benefitted him the way it had for so many other Australian batsmen. “The experience was good for him. He’s had to work hard and dominate first-class cricket ... Now he’s had an extended run in the middle order, which is where he should be.

“The best thing they did for Steve was take him out of the short form for a year. It allowed him to work on his technique and shot selection. That was what was letting him down at Test level, knowing what shots to play when. He had all the shots, he could play everything, but knowing what shots to play when ...

“It’s set him up to be a better short-form player as well.”

Curiously, while Smith is now a lock for the Test side, he’s trying to work his way back into the one-day set-up. Next February’s World Cup is a high priority; being a first-choice name on every Aussie team sheet is a point of competitive pride. His status within the team raised another consideration, one that’s right in line with the SR Waugh track. Smith’s re-emergence on the national level has also revived chatter about his prospects as a future Australian captain.

If this was the corporate world, Smith has that quality that you’d call “management material”. In some respects, should he continue to develop into the type of top-order player that commonly gets first look at the captaincy, Smith presents a neat fit for the role, arguably better than recent holders of the office – he has neither the flashy, celebrity inclinations of early-days Clarke, nor the rough edge that defined the younger Ponting.

Already, Smith has captained NSW (to Shield victory, no less), the Sydney Sixers in the Big Bash League and has been a stand-in for his IPL sides. While not a vocal leader – dad Peter characterises his son as tending to introversion – he’s not a personality that will engulf the dressing room, either. Jaques, who’s captained sides that Smith played for, then watched Smith lead the same sides when he was away, says the young man’s mentality is what makes him well-suited to the captaincy. “He’s a student of the game, and he doesn’t let things roll along when it comes to his captaincy. He’s a forward-thinking guy. As he matures and gets more comfortable in his surroundings, I’ve got no doubt he’ll be able to be the man-manager that Australia needs after Clarke retires.

“He’s a quiet sort of guy, but when it comes to his cricket, he’s got an aggressive edge to it. Whether it’s batting or bowling, he’s always trying to win the game. And I think that transfers to his captaincy.”

Smith, predictably, is circumspect about the possibility of leadership. “It is something I enjoy doing. At the moment, though, I’m happy doing well, batting well, scoring runs and winning games for whichever team I’m playing for. That’s my main focus and something I’m trying to improve as well.”

There is a long season ahead, running almost continuously from the Tests against India through to yet another Ashes series in the middle of next year. And if the recent experience of Australian cricket is anything to go by, the way the lows turned to highs is a reminder of how easily it can turn back – the recent one-day loss to Zimbabwe, the first in three decades, was evidence of that. Putting wins on the board has settled the playing group of late, but as was noted after the Ashes, this “new” Australian side wasn’t exactly young and was still dependent on the contribution of some veteran figures. Smith’s youth is a valued part of the mix.

“It’s been a big part of our success recently; we’re a close group,” Smith says. “We’re relaxed, we’re able to play with freedom, and that’s the way you play your best cricket. With regards to the captaincy, that’s quite important – the tactical, on-field sort of things are the easy part. It’s about making sure you’ve got a good environment and your group’s working toward the same goal.”

It’s a philosophy that Smith may eventually have to put into practice. In time, the noticeable thing won’t be the middle initials, but the (c) next to his name.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open