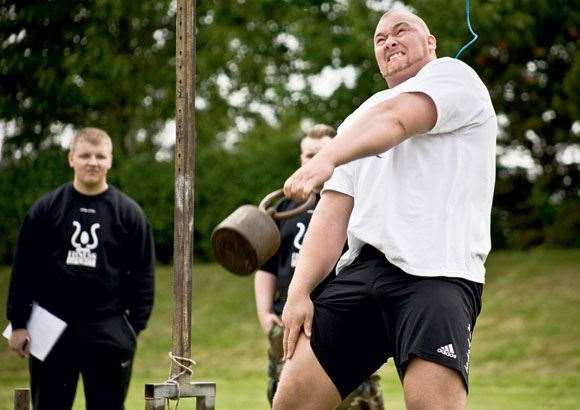

The sport of strongman combines the disciplines of powerlifting with a host of events designed not just to test an athlete’s strength, but also their physical endurance

Asher Floyd

Asher FloydThe sport of strongman combines the disciplines of powerlifting with a host of events designed not just to test an athlete’s strength, but also their physical endurance

Heisi Geirmundsson looks like he spends his weekends looting monasteries, deflowering maidens and knocking back horns of mead with his mates at the Valhalla RSL. A coarse, red beard covers his battered face; runic tattoos spill over his neck and bulging arms. If you still don’t know what he is, just ask him. “I’m a Viking,” he’ll answer matter-of-factly, “like my ancestors before me.” Anywhere else in the world, Geirmundsson would be considered an A-class eccentric; in Iceland, he’s a respected athlete.

The sport of strongman combines the disciplines of powerlifting with a host of events designed not just to test an athlete’s strength, but also their physical endurance (throwing boulders, pulling trucks, things like that). Geirmundsson the Viking belongs to a rich and intriguing strongman heritage. Iceland, with a population of just 320,000, is the traditional powerhouse of the sport, with an impressive history in the Highland Games, a host of world records in individual events, and the most World’s Strongest Man titles of any country (eight) – one more than the US, which has 1000 times as many people. I’ve come to Reykjavik to find out why Icelanders are so strong. Geirmundsson is providing an early clue: up here, strongman isn’t a sport; it’s a lifestyle.

“To understand Iceland’s success in strongman,” says Gudmundur Saemundsson, a cultural historian at Reykjavik University, “you must first understand that our linkto the past is very real.” Contemporary Icelanders, Saemundsson argues, are linguistically and ethnically identical to their Viking forebears, a reflection of centuries of geographical isolation followed by some very strict immigration laws. Consequently, many Icelanders profoundly believe they are the living embodiment of their ancestors. It gets weirder: not only do some people here brew their own mead and make their own medicine according to Viking recipes, but nearly 1500 people practise Asatru, a religion based on the worship of the ancient Norse gods.

As far as strongman is concerned, the linguistic link to the past is perhaps most pertinent. While the other Scandinavian languages have evolved to the point where they’re unintelligible with the Viking tongue of Old Norse, Icelandic hasn’t, allowing Icelanders to read the Viking sagas – sagas which, along with recounting tales of raping and pillaging, contain many accounts of informal strength contests. “It’s kind of random,” says Stefan Solvi Petursson, Iceland’s current top-ranked strongman and world number-four. “You’ll be reading about some blood feud or battle, then, suddenly, characters in the saga start seeing who can lift a boulder the highest or carry the biggest load.”

The Norsemen valued physical strength on a par with your ability to sail a longboat or grow an Asterix handlebar, something which may explain why strongman appeals to modern-day Vikings. As Solvi Petursson puts it, “We used to be a fearsome nation, and we are not yet ready to be a little country with no influence. Nowadays, killing monks and stealing women isn’t acceptable, so we lift boulders and throw barrels instead!”

The idea that strongman provides a PC platform for Icelanders to bully the world is an interesting one, and could also explain the country’s predilection for grounding aeroplanes with unpronounceable volcanoes and screwing over English retirees with dodgy offshore savings accounts. But there is another possible explanation for Iceland’s disproportionate success at strongman: that Icelanders are genetically stronger than everyone else. When I pose this to ex-four-time World’s Strongest Man winner Magnus Ver Magnusson, he gives a cheeky response. “Absolutely! I used to joke with Regin Vagadal [a strongman competitor from the Faroe Islands] that the Norwegian Vikings who settled Iceland stopped halfway at the Faroe Islands to drop off their weak and sickly!”

Ver Magnusson’s jokes aside, the theory may have merit. On a dark winter’s night in 1984, a fishing trawler capsized off Iceland’s south coast. What happened next has confounded scientists ever since. While four of the five crew quickly succumbed to hypothermia and drowned, the fifth didn’t. Despite being equipped with nothing more than bare feet, jeans and a jumper to combat the five-degree water and minus-two-degree air, Gudlaugur Fridthorsson swam for six hours before hiking another half hour to safety. Subsequent tests revealed that Fridthorsson is a kind of superhuman, with a unique muscle and fat structure that more closely resembles that of a seal than a human. Moreover, not only was Fridthorsson found to be a direct descendent of the legendary Viking outlaw Grettir the Strong, but his “seal gene” is thought to be recessive in Iceland. Although no tests have been conducted into the genetic makeup of local strongmen, many here believe Iceland’s harsh climate has resulted in a contemporary gene pool purged of weaklings – a kind of “survival of the strongest”.

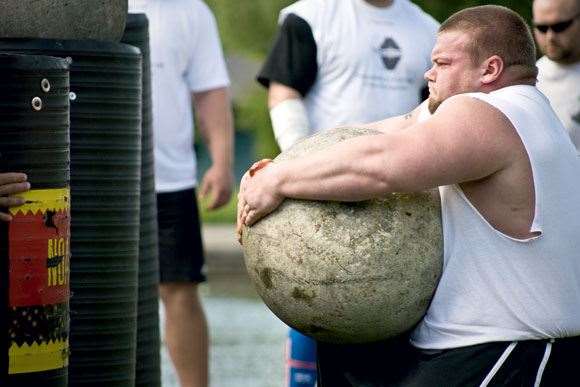

So is it nature or nurture? In a country where up to ten per cent of the population believes in elves (seriously), I’m not too sure whose opinion to trust, so I decide to check out a strongman competition for myself. On a sunny summer’s day in a Reykjavik park, Iceland’s Strongest Man is being held. The country’s perilous financial situation means there’s no money to splurge on trucks to haul this year; instead the competition consists of five events involving lifting, carrying and throwing various weights and implements. Most spectacular is the “Atlas stone loading” where competitors are timed as they put five 200kg-boulders into five upturned pipes of differing heights.

Despite Geirmundsson’s best Viking impersonations, the title is won by Solvi Petursson, with second place going to Benedikt Magnusson, a man who recently became the first person to deadlift a 500kg-Hummer tyre. The talking point in the crowd is third-placed Hafthor Julius Bjornsson, a 21-year-old widely tipped to be Iceland’s next world champion. At 205cm and 180kg, he doesn’t resemble a Viking so much as a monster from a Viking saga.

The very fact there’s a crowd could explain Iceland’s success at strongman; what would be a minor event elsewhere is a big deal here, with TV cameras, flag-waving grandmas and enthusiastic young autograph hunters. Strongman attracts healthy participation levels and media coverage in Iceland and has even entered the local vernacular; when the odds are against you an optimist’s response is often “Ekkert mal fyrir Jon Pall”. An ode to the late Icelandic strongman legend Jon Pall Sigmarsson, it roughly translates as “it’s no big haul for Jon Pall”.

Back at my desk in Australia months later, I’m still struggling to determine the secret to Iceland’s strongman success. For one last opinion I email Arnar Palsson,

a geneticist at the University of Iceland with a “particular interest in evolution and developmental biology”. Palsson agrees that my three theories – try-hard Vikings, genetics and popularity – are all plausible explanations, though he thinks the existence of a “strongman gene” in Iceland is unlikely. But Palsson’s own take on his country’s excellence in strongman is something that hadn’t even occurred to me, and in retrospect probably explains why I didn’t see any drug-testers at Iceland’s Strongest Man. After carefully considering my three theories, Palsson concludes his email thus: “Alternatively, it could just be down to a truckload of steroids.”

Asher Floyd

Asher Floyd– Sam Vincent

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open