FEATURE STORY: Major League Baseball has arrived in Australia like a fastball over the plate.

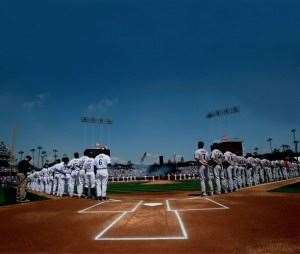

From Chavez Ravine to Sydney's Moore Park, Major League Baseball's world-wide journey continues. Photo: Getty Images.

From Chavez Ravine to Sydney's Moore Park, Major League Baseball's world-wide journey continues. Photo: Getty Images.“To survive in Brooklyn one had to be a dodger of trolleys ... the baseball team became the Dodgers during the 1920s, and the nickname endured after polluting buses had come and the last Brooklyn trolley had been shipped from Vanderbilt Avenue to Karachi.” – Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer

IT’S about the caps, you see. The caps worn fashionably around town, on hipster heads everywhere, nodding to the style of baseball without much thought to the substance. You have those ubiquitous Yankees caps, screaming Gotham urbanity. Increasingly, you’ll find a Red Sox cap, symbolic of a person partial to the grittier, more authentic Boston vibe. That random Mets cap? Probably a misled soul who went on holiday to New York, and somehow found their way to Shea rather than the Bronx.

Then there’s the Dodgers cap, less seen but worthy of a place in the fashion. It’s a classic; a shade of azure that evokes a feeling of Los Angeles, yet also reaches the ballclub’s roots in (pre-hipster!) Brooklyn. There is actually a colour called Dodger blue. This is a cap that says: this is a team with a history, that has a place in the culture.

“They have an aura; it was a special place to be able to get an opportunity,” says Craig Shipley, the pioneering Australian whose 11-season major league career began in 1986 with Los Angeles. Indeed, the motif of Dodger history is the cultural expansion of baseball, and the rest of the nation with it. Early 20th-Century Brooklyn was a nest of immigrants and first-gen kids, who took to the lovable-loser Dodgers as their common identity. Most famously, it was the place where Jackie Robinson arrived to break down the majors’ de facto segregation against African-American players. As Robinson took to the field every day, a one-man protest more than a decade ahead of the civil rights movement, it became the game’s proudest moment, and remains so.

The end of Robinson’s career also marked the end of the Dodgers’ tenure in Brooklyn. In a move akin to taking the Magpies out of Collingwood, team owner Walter O’Malley moved the club to Los Angeles for the 1958 season. The relocation came as a shock to what was a much smaller America – the westernmost team in the majors to that point was in Kansas City, and the cities of the Pacific coast were regarded as distinctly provincial. But the arrival of the Dodgers in LA, as well as the Giants in San Francisco, was confirmation in itself that these were now big-league towns.

Brooklyn never forgave O’Malley. The westward tilt of the country was inexorable, though, and the Dodgers’ years in LA have become as venerable as those in the New York borough. The Dodgers’ first wholly LA star was Sandy Koufax, the legendary left-handed pitcher of the ’60s, icon to Jewish-Americans everywhere, and that rare species of sporting great who left at the peak of his game, retired at 32. The drumbeat continued: the 1980s saw the emergence of a flamboyant Mexican pitcher, Fernando Valenzuela, who established a lasting affinity between the club and its Latin fan base; in the ’90s, Hideo Nomo became the bridge that spanned the previously separate baseball establishments of Japan and the US, a trade relationship that continues to thrive.

“The Dodgers are the pioneers of the game worldwide, to a large degree,” says Shipley, recalling the visit of two LA coaches to Sydney in 1978. For a kid whose only exposure to Major League Baseball was watching condensed coverage of the World Series on reel-to-reel footage at the Auburn baseball club, this slight link was enough to fire Shipley’s imagination. “That made an incredible impression, seeing coaches in Dodger uniforms on the field.”

Three and a half decades later, there will be a whole lot of Dodger uniforms, along with those of the Arizona Diamondbacks on a field in Sydney. This week the teams will open a major league season for the first time in another hemisphere. The MLB has held opening-day games beyond its base on five previous occasions, in Mexico, Puerto Rico and most recently Japan. But bringing honest-to-goodness regular-season games to Australia represents baseball’s boldest claim-staking yet, and is a sign of the American pastime’s now-global designs.

When Dodger Zack Greinke was thrown at last year ... Photo: Getty Images.

When Dodger Zack Greinke was thrown at last year ... Photo: Getty Images.The major league’s links to Australia are not particularly deep, but in keeping with baseball’s antiquity, they are old. The top baseball stars first came to this country as part of the celebrated 1888-89 world tour organised by Albert Goodwill Spalding. A star pitcher, official and, yes, sporting-goods magnate, Spalding was muscle-flexing in pure, Gilded Age-America style, making it his mission to bring his still-youthful sport to the world. The original plan was to seed the game among the colonial brethren in Australasia, but the itinerary grew to encompass Egypt, Britain and Ireland.

... the benches cleared, just as the Down Under series was being announced. Photo: Getty Images.

... the benches cleared, just as the Down Under series was being announced. Photo: Getty Images.While its grand scope made it a success, the tour devolved into a sideshow-filled promotion for Spalding’s sporting goods. Spalding’s bold personality quirks – a follower of an occult religion, he was also known for flat-out fabricating the origin story that baseball was invented by Civil War general Abner Doubleday – had long earned him detractors among serious baseball men. They held on to the idea of a better-run world showcase for the game, according to author James Elfers in his book The Tour To End All Tours, and when the opportunity arose to stage another global jaunt on the 25th anniversary of the Spalding tour, the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants ventured forth to Australia and points beyond.

The great American wit Ring Lardner noted the trip had two purposes – to prove Ireland was “the greatest country in the atlas” (working-class Irish stock dominated the major leagues at the time) and convince “the foreign element that baseball is better than cricket”. Even though this was meant to be the better baseball tour, some showy touches were added. Jim Thorpe, the athletic marvel of the 1912 Olympics who had been stripped of his gold medals because he had played a couple of seasons of minor league baseball beforehand, signed on. So did various all-stars from other teams, although one exception was the game’s pre-eminent player, Ty Cobb, who declined his invite. The reason was probably money – it’s part of the tight-fisted Cobb’s legend that on his deathbed, he had a brown paper bag containing a million dollars of bonds next to him – but it’s equally likely that Cobb’s even more notorious bigotry towards non-whites and non-protestants stopped him from going.

The Sox and Giants played games in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne, taking on a variety of local outfits as well. The differences in sporting culture consumed observers – Australian newspapers remarked upon the brash, talkative comportment of the Americans on the field; the big leaguers were surprised at how cricket-attuned crowds would cheer simple fly balls caught and base runners thrown out. Although organisational difficulties prevented games being played in visits to Adelaide and Perth, the Australian portion of the tour ended on good terms. Giants supremo John McGraw promised a return.

World war and financial depression ended many of the grand visions dreamed up during the turn-of-the-century period of globalisation. The Dodgers-Diamondbacks series marks the 100th anniversary of that visit, underscoring just how much time has passed. Four years after their world tour, the White Sox were embroiled in one of the worst scandals in sports history, when a group of Chicago players accepted money from gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series. It was a historic low, but it was also a crisis that didn’t go to waste – the game would reform, Babe Ruth appeared, the Yankees won a lot and baseball’s five-decade-long golden age followed. The America that emerged during and then boomed post-war was more than enough to fuel the game.

*****

FORWARD to the present, and we’ve arrived at possibly the most curious moment in baseball history. The game’s outward signs of health are positively ruddy. MLB revenues have swelled to $8 billion a year, the commercial wellspring that underwrites the largest contracts in team sports, such as Dodger ace pitcher Clayton Kershaw’s recent seven-year deal worth $215 million. Attendance was more than 74 million last year, nearly matching the record crowds of 2012 (to get a sense of proportion, the AFL gets just under 7 million, the NRL 3.5 million, albeit with vastly fewer games). Tension between the players and owners – baseball’s most persistent source of conflict in the half-century after the war – has been resolved while other sports continue to struggle. And while there’s always griping about competitive balance and the rich club-poor club divide, it was interesting to see last season that three of the top five highest-spending teams made the playoffs, but so did three of the five lowest spenders.

And yet ... there’s a nagging sense going around that baseball isn’t quite what it used to be. This feeling was encapsulated in a discourse-sparking piece in The New York Times last September by sportswriter and author Jonathan Mahler. “The game has never been healthier,” Mahler wrote. “So why does it feel so irrelevant?”

The story touched off a backlash cycle – baseball diehards have become accustomed to what they call the “Baseball is dying” sub-genre of sports stories. But even though the sport continues to rake in money, the critique does have legs. Baseball has decidedly ceded ground to the NFL in the culture. When Bruce Springsteen changed the words to Glory Days at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2009 (“I knew a man who was a football player”), it underscored the idea that if he'd written the song today, it wouldn’t be about a high school baseball star.

The NFL pulls in even more cash than baseball and absolutely slaughters it on television – preseason football games will commonly out-rate baseball play-off contests. MLB’s lack of traction on national TV has created a bizarre scenario in which baseball’s stars are big in their own city, but don’t sell beyond it. Forbes’ most recent list of the 100 richest athletes contained 27 baseball players, but only two – Derek Jeter and Ichiro Suzuki – made $5 million or more from endorsements. By comparison, eight of the 21 NBA stars on the list drew that kind of money from off-court exposure.

The more pressing issue for baseball, however, is demographic. The way young people view the game (or not, as it were) has become a major concern. Research by Nielsen found the average age of the 2013 World Series viewer was 54.4, up from 49.9 four years ago. Only 4.3 percent of viewers for the League Championship Series were under the age of 17, a rate less than half of what the NBA gets. Participation in Little League, that bastion of Americana, has declined by a quarter over the last two decades. A particularly dramatic sign of shifting attitudes toward baseball has been in the number of African-Americans in the game – from accounting for 19 percent of major leaguers in 1986, it has dwindled to 8.5 percent. Baseball is dependent on an ageing base of followers, which has led to ESPN columnist and Red Sox uber-fan Bill Simmons to deride the sport as “the new golf”.

The greying of its fans, and the sport’s embedded nostalgia, has created a push-and-pull identity crisis – honour tradition or embrace modernity? – that would sound utterly familiar to cricket purists debating a T20 future. Baseball’s most recent epoch has exposed this fault-line in the starkest manner. This season will mark 20 years since the strike of 1994, which wiped out the second half of the season. The players, incensed at owners’ plans for a salary cap, walked out in August. The two World Wars couldn’t prevent the World Series going ahead, but it went unplayed in 1994.

The strike has particular resonance for Shipley, who was then with San Diego. “I can remember it well, because the Saturday night game – the strike started after the day game on Sunday – we were in Houston, and I was hit in the head by [a pitch from] Darryl Kile, and briefly knocked out. The next day, because things weren’t going well [with the strike negotiations], our manager Jim Riggelman said to me, ‘You need to play because we may not be playing tomorrow.’

“I remember leaving Houston, going back to San Diego, staying there a few days. Everyone went their separate ways, and it didn’t get resolved. For me personally, it was not a good time to go on strike, because I was having the best year of my career.

“It should’ve never happened. It should never happen again ... I don’t know what the attendance was in 1995, but yeah, if your team did that to you, it would leave a bitter taste in your mouth.”

In trying to recover the ground it lost with the public, baseball went through another period of reform, but also hit an almighty stumbling block. The number of home runs being hit went through the metaphorical roof, highlighted by the 1998 chase for the single-season record by Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa. It went ignored at the time, but looks obvious in retrospect – the homer explosion was fuelled by widespread steroid abuse.

Baseball's $215 million man Clayton Kershaw. Photo: Getty Images.

Baseball's $215 million man Clayton Kershaw. Photo: Getty Images.Baseball’s drug policy had been a casualty of the conflict between the owners and players, a detail that was overlooked as they squabbled over money. The fans dig the long ball, and this was the most obvious way to get them back in the seats. But for a sport that prizes its past, the steroid era has shredded the record book and ransacked the Hall Of Fame. Its effects are still being felt – Alex Rodriguez, the most gifted player of his generation, will be suspended for this entire season for drug use.

Baseball is criticised for being hidebound, but has ventured significant changes since 1994. The most obvious might be the likes of the Arizona Diamondbacks, a team that joined the majors in 1998, and won a championship four years later. They are representative of the sport’s new age – a start-up outfit in one of the fastest-growing metro areas in America, now the sixth-most populous city in the US, named after a species of rattlesnake, playing in a stadium noted for its swimming pool/spa over the right-field fence. Under commissioner Bud Selig, there's been a record of innovation: expanded play-offs, interleague play, an embrace of new media and a newly rigorous drug-enforcement policy. Things surely have changed in baseball, if only because the Red Sox are now regularly winning the World Series (the Cubs, alas ...)

Ultimately, baseball’s present issues are the product of the monoculture fracturing to pieces. Much like the pop music industry, it was once able to shape tastes from its privileged position. Now, it must figure out its place among a world of options. Ironically, the rest of the world is where they might go looking.

*****

IN 1996, Shipley was part of the San Diego Padres team that played the first MLB regular-season game outside of the US or Canada, in northern Mexico. Shipley’s old Dodger team-mate, Fernando Valenzuela, had joined the Padres, and pitched the first of the three-game series. “That was special, for him to pitch in front of his home country in Monterrey,” Shipley says.

There had been great Spanish-speaking players before Valenzuela, but the Mexican’s popularity pointed to a new class of Latin American star that would remake the majors. As the West Indies’ cricketing greatness has receded, its Caribbean neighbours have flourished in beisbol – the Dominican Republic is the single biggest producer of big-league talent outside the US, with 89 players on opening-day rosters last year, and Cuba (15 players) could be an equivalent source, if its diplomatic relationship with the US could ever be resolved. With other staple baseball outposts in Venezuela, Mexico and Puerto Rico contributing, the proportion of non-US born players in the majors was 28.2 percent in 2013.

Dutchman Didi Gregorius. Photo: Getty Images.

Dutchman Didi Gregorius. Photo: Getty Images.One of baseball’s more intriguing trends is the variety of places that talent is emerging from. When Shipley’s playing days ended in ’98, his career moved into the scouting department, working first for the Red Sox during two of their World Series victories, and now in a role with the Diamondbacks. True to his own path, he’s trying to uncover players in uncommon origins.

“Europe’s growing, [it’s] very organised. I’ve been surprised by the Dutch, with the facilities they have,” Shipley says. “Then you have hotbeds like Curacao and Aruba, two tiny little islands that love baseball. You go to a Little League tournament in Curacao and they’ve got three leagues there. The enthusiasm the kids play with, the atmosphere with the music, it’s just a fun place to watch baseball.”

Australia, historical home to 31 major leaguers, still rates as potential rather than established hotbed. Shipley calls his homeland the most competitive market for athletic talent in the world, and even though the pipeline he helped create sends scores of Aussies to the minors every year, only two were to be found on opening-day rosters last season. This week, prior to the major league games, Team Australia will have the opportunity to play both the Dodgers and Diamondbacks, and such opportunities can be rewarding – the story of Peter Moylan, who went from salesman to Atlanta Brave hurler after his performance in the 2006 World Baseball Classic, is a part of Aussie baseball lore.

An international presence is already established within the game – the logic follows to take baseball to the rest of the world and connect new fans to it. It's seen as a key part of Commissioner Selig's legacy, which has been brought into focus as he departs office in 2015, after 20 years at the helm. If inadvertently, the old joke about the “World” Series involving teams from two cities in the same country no longer has quite the same sting. Every Major League Baseball game is an international swirl, and the sporting character world-class.

The setting for this series will be special – the SCG will be the oldest place baseball is played this season, predating the cathedrals of Fenway and Wrigley. The Dodgers and Diamondbacks have brewed quite the rivalry, spiced by a June encounter in which they staged two bench-clearing brawls.

Cuba's Yasiel Puig; typical of the new diamond talents being unearthed from all over the world. Photo: Getty Images.

Cuba's Yasiel Puig; typical of the new diamond talents being unearthed from all over the world. Photo: Getty Images.As far as name recognition goes, the honour is Dodger manager Don Mattingly's, the former Yankee star better known in these parts because Mr Burns insisted he cut his sideburns in The Simpsons. The $215 million man Kershaw, who spent his offseason helping orphans in Zambia, is widely considered the best young pitcher to come along in years, while Arizona slugger Paul Goldschmidt is a favourite of the Moneyball-loving stat-heads who have revolutionised baseball appreciation.

In line with baseball’s new globalism, the two teams have stars from farther afield. Diamondback shortstop Didi Gregorius, one of Shipley’s promising Dutchmen, is poised for a breakout year as one of the majors’ slickest glovemen. Then there’s Dodger outfielder Yasiel Puig, whose electric appearance as a rookie turned around LA’s 2013 season. Puig’s appeal is old-school visceral: he swings wildly, runs hard, crashes into walls. The 23-year-old Cuban has a definite air of wild mystery – his defection via Mexico, after several failed attempts, may or may not have been aided by drug cartels, something which Puig doesn’t do much to confirm or dispel.

The Show, true to its name, doesn’t lack for spectacle. The opening to the 139th season of Major League Baseball (depending on how you care to count them) will be a little different to the others before it. And in its own way, it’s a vision of what baseball’s future could be. Welcome to the multi-national pastime.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open