Matt Shirvington, the athlete, attracted plenty of headlines.

John Steffensen has chimed in too, winning the individual there, and a couple of guys have gone well and truly under 45secs for the 400m – Offereins, Joel Milburn and John. There’s a bit of depth there, so that’s exciting.

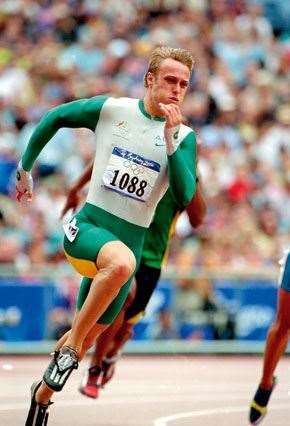

"Shirvo" in Full Flight Sydney 2000

"Shirvo" in Full Flight Sydney 2000Images: Getty Images

And off the track? How are we looking?

The men’s long jumpers are continuing to do extremely well. Mitchell Watt won the national championship – I think he jumped 8.44; the Australian record is 8.49. He’s also the bronze-medallist from 2009. Then you have Chris Noffke and Fabrice Lapierre. Fabrice finished second in the world overall last year and won at the Commonwealth Games last year, too. He’s probably jumped the best out of those guys. He’s jumped an 8.78, which is a huge jump. That would win any major championship title at the moment. It was slightly wind-assisted, but it just goes to show he’s capable of jumping that sort of distance. And then Dani Samuels is the defending discus world champion. She’s a good chance to take that out again. She didn’t go to the Delhi Commonwealth Games, so she’ll be pretty keen to do well and is capable of winning. She’s only 23, so she’s still very young, particularly for a thrower. The girl she beat at the last Worlds I think was the oldest in the field, she was about 37-38. And there’s Dani, at 22, taking it out. She has a massive future.

This is all well and good, but isn’t Australian athletics supposed to be in the middle of a lean patch, talent-wise?

When you break it down like we just have, it’s not too bad, actually. We have some good athletes. We have some good distance runners as well. Craig Mottram’s back in decent shape and doing fairly well. Then there’s the shorter-distance guys – the 800m and 1500m runners – who are quite good. Jeff Riseley and Lachlan Renshaw and Ryan Gregson, he’s a great talent. He’s only 21 as well. There’s definitely some young people to watch out for.

What’s your position in the “relevance of the Commonwealth Games” debate?

I don’t see them going away, but I think their popularity will always ebb and flow. Delhi made people look forward to Glasgow 2014, which is going to be off the back of the London Olympics. Glasgow is going to know it has a responsibility of reinventing the Commonwealth Games.

Look, I think we have a lot of major championship sport these days and the small events seem to be getting bigger, especially with broadcasting and the following they have from viewers and supporters. I think people are getting their fill. Throughout the year it’s becoming more difficult for people to stop everything and turn their attention to a Commonwealth Games or an Olympic Games.

We can imagine sprinting is a solitary pursuit at times. What motivated you in your prime?

Just that autonomy you work on so much in training. Sprinting is one of those sports that involves rudimentary action. Anyone can do it. But at the top it’s all about honing that skill to a point where you mirror every step identically, all the way to the end, and give yourself every opportunity to do that without over-thinking it, without muscling it too much, trying too hard.

If you tell the average athlete to relax, they’ll slow down. With a top-level track athlete who you know is going to run well, when you tell them to relax, they get faster. It’s strange. I probably only felt that one or two weeks of the year, where it actually all came together, but that was the motivation for me, to taste that each year. Sometimes it would be the right two weeks, sometimes too early, too late. Very often you see athletes cross the line and they’re like, ‘That was easy, I could’ve run faster.’ That’s the feeling you want. You want it to be easy without even thinking about it.

How much did your rivalry with Patrick Johnson help Australian sprinting?

I don’t want to dwell on it too much, but Patrick and I definitely had a rivalry that I think was beneficial to both of us and I think in the end, beneficial for the sport.It certainly made us work harder. There were times where I wasn’t ready to run fast and Patrick came out and ran fastand vice versa. Underneath us, we had four or five other guys who were used to getting away with running 10.50, but now had to run 10.20-30 for the 100m, so they were elevating their progression as well. I think that’s what’s lacking at the moment. Aaron Rouge-Serret is by far and away the best Australian right now, but he doesn’t have a rival. He doesn’t have anyone right there pushing him, and so pulling the rest of the guys up with him.

When did you realise you were a bit faster than the other kids and that maybe you could make a career out of this sprinting game?

The assumption was that I was completely dominant as a kid. It wasn’t just the 100m, it was the long jump and the high jump. I was pretty good, but I wasn’t the best. I used to go to Little Athletics and I’d get beaten. I was never far and away the best natural athlete – and I always knew that. Even at a state level, I wasn’t great. At the first nationals I went to as a 16-year-old, I got knocked out in the first round – wouldn’t have been in the top 50 at that championship. It was mum who eventually said, ‘You know what, you haven’t really worked for it yet, so why don’t you do a bit of training?’

So as a 17-year-old, I started training with my first coach, a guy called Michael Khmel, who took me from running 11.20 to running the national junior record of 10.29 within 12 months.

How did you handle the “Great White Hope” tag?

I never got caught up in it. I never used it as my tagline or anything like that. I was able to train with some of the best athletes and coaches in the world. That came off my ability as a runner, not the colour of my skin. There’s always going to be people trying to make you something you’re not. I was adamant that, regardless of the colour of my skin, I wanted to be a better athlete. If I was the fastest white guy, and I was only ranked 20th in the world, I would much rather be fifth fastest in the world.

‒ James Smith

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

England held top secret commando training with royal marines before World Cup