Max Walker has reinvented himself time and again; from batsman to bowler, from radio star to television face, from architect to writer.

Max Walker has reinvented himself time and again; from batsman to bowler, from radio star to television face, from architect to writer.

From a one-time self-confessed “fountain pen dinosaur”, Walker has emerged and reinvented himself time and again; from batsman to bowler, from radio star to television face, from architect to writer. It’s often forgotten that before his Test and 17-ODI career, he starred in the then-VFL, clocking up 85 top-grade games for the Melbourne Football Club between 1967-72.

Today, the 64-year-old is a media tech guru, having set up a company, bhive Group, which specialises in mobile web platforms, streaming media, QR codes and analytics ... We don’t know what any of that stuff is, but Big Max does. We wanted to get his thoughts on cricket’s transformation in recent years, so we stole him away from the Movember campaign trail for a slice of Walker wisdom.

Besides the bleedin’ obvious, what inspired you to become a Mo Mentor for Movember?

It seemed like too many boxes got a tick. I’ve had a big moustache all my life, and men’s health is very close to me. Most weeks, someone near and dear is either being diagnosed with prostate cancer or anxiety attacks or depression. It’s something you have to take very seriously. And if, in a small way, I can make a difference, by being part of this critical mass of humanity that’s putting its hand up, albeit for a moustache, then it’s pretty symbolic, isn’t it?

Did you ever think one day that your mo would be behind such a good cause?

I initially grew it, and it did take a while, when I was about 20-odd, and it came in really handy in the West Indies because it was so hot over there. I do smile a lot; the tendency was for my lips to crack. I thought, ‘I’ll put a shade on it.’ It’s part of my DNA. I guess I’d feel that I wasn’t complete if I ever lost it.

There was certainly a lot of facial hair being flashed around on the mini-series Howzat a month or two back ...

For the ’73 tour of the West Indies, which occurred a few years before when Howzat was set, almost everyone in the side had a moustache. There was a tendency to almost link the sideburns up with the mo, but it was an unwritten team rule that there had to be an inch gap, or 25mm, from the bottom of the moustache to the bottom of the sideburns ...

What did you make of the factual accuracy of Howzat ... Did you find yourself nodding your head while reminiscing about the ol’ days?

I thought the first part, in particular, of Howzat was fantastic. As players, we weren’t privy to a lot of the conflicts and confrontations behind closed doors, which were Kerry Packer’s wars, but you have a better appreciation for the anxiety he went through, in getting so many doors slammed in his face. And yet he believed in the idea on a couple of levels. A , he loved cricket. And B, he wanted it to be a marketing magnet for his television station, and the only way that was going to be achieved was if we committed to one another and didn’t pull out. As it was, West Indian Alvin Kallicharan and Jeff Thomson eventually did, but the strength of it was ... he just eyeballed everyone and walked around and asked, “Any reason you won’t give me 55 days of your life for World Series Cricket?” And we all said, “No, Mr Packer.” Only David Hookes was a little apprehensive about it, but once he was across the line, the rest of it is, as they say, history. Great television.

What do you remember most about your switch from Aussie rules to cricket?

It wasn’t a conscious decision. For me, it was an evolution. Most of life’s journey is meandering, like a switch-back railway, or whatever way you want to describe it. I was chosen to tour the West Indies in 1973. I had my architecture thesis to complete at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology when I came back. We didn’t get back until May that year. The footy season had started, obviously ‒ about five games in, so I had to make a choice. I didn’t think it was possible to be really successful at all three, so I retired from footy and I got through my architecture; I had to submit a month or so early in October so I could take on my cricket itinerary, and I just never got back to footy. At the ripe old age of 22, I’d had 85 senior games ... I never “retired”,

I just never got back to it.

Your career switch was a big one compared to today’s mere footy code-hoppers, hey?

I guess a lot of that was going on back then. Brian McKechnie, who played in the underarm incident, was a dual international. He played for the All Blacks. He was there at the crease when Trevor Chappell bowled the ball along the pitch. He threw his bat on the ground ... I was at fine leg, actually. That was the last game I played for Australia. I thought, “My goodness, he’s upset.”

Simon O’Donnell would’ve been the last bloke to do it; he played 26 or 27 games for St Kilda in the VFL, a handful of Test matches and 98 one-dayers. It’s a pretty unique group, though. There’s probably under ten who have played both Test cricket and AFL footy.

Speaking of uniqueness, is that something modern cricket could benefit from, more characters and personalities like there seemed to be in your playing days?

It was a game when we played. We were good enough to get picked to play this game for Australia. We would’ve played for nothing; we pretty much did. We got $400 before tax for a Test match, including the Centenary Test match when we signed up for World Series Cricket. Today, if you’re a good player, in the Twenty20 sense, some of the top players are getting two million bucks for 50 days in the IPL. Then you have one-dayers and Test matches as well. These guys are mega-million-dollar players. You’d have to do some research on the exact amounts of money, but when you think that 400 million sets of eyeballs tune into an IPL final or a World Cup final, then you can see the magnitude of Kerry Packer’s influence.

What was the best piece of batting advice you ever received?

The best coaching book I have ever seen, and I got it for my 12th birthday (my dad gave it to me, Big Max), was The Art Of Cricket by Sir Donald Bradman. That suggested, as a batsman, that you try and tread on the ball ... if you’re successful, you’ll break your ankle. Anyway, the idea was to pick the pitch of the ball. Second, it suggested that you “sniff” the ball; in other words, you get your head down over it, and you play with a very straight bat. And that worked very well. My last two knocks for North Hobart in district cricket batting at three were 117 and 119. That will probably shock you and a lot of other people, but I saw myself as a batsman!

How does a batsman who scores centuries become one of Australia’s best-known bowlers?

The Melbourne Cricket Club didn’t have a fast bowler, and I batted at ten in my first match. It was 14 weeks before I got a hit. While I opened the bowling at school, I’d taken one district wicket for North Hobart, and I’d been playing with them for five or six years, so how did it all happen? My first game for Victoria was a Colts match the year I came across in ’67; Dennis Lillee was 12th man for Western Australia. Rodney Marsh played, and there was a guy named Bruce Yardley, who opened the bowling for Western Australia, who turned out to be one of the great off-spinners that we’ve ever had. So life was very different, wasn’t it? Peter Bedford, the Brownlow medallist, played in that match, the late John Scholes, Les Joslin, there were some amazing names. But yeah, I thought I was a batsman.

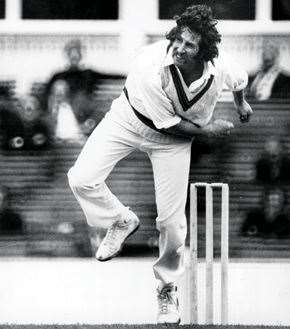

Your front-on bowling action is one of the more interesting styles from over the years. How did it develop?

Just to get ahead at recess and lunch at school, really. Right arm over your left ear, ol’ legs crossed at the point of delivery ... fabulously mechanically perfect before biomechanics was even a word! I was never bio-mechanically perfect, but Lillee broke down ... I didn’t break down.

You developed into a cult hero ... who were your idols as a player?

Viv Richards was probably the best batsman I bowled against in my time. I like to brag that I got him out a couple of times ... for 181 and 179. But he really was the crown prince in those days. He was probably the most complete cricketer I had ever seen. He fielded beautifully, he bowled medium-quick, bowled spin, and was one of the truly great all-rounders, with Sir Garfield Sobers, who I only played against once ‒ when he played for South Australia.Of the bowlers, well, Lillee was just the best. He was an amazing machine when he walked through the gate and onto the field. He became this menace; technically brilliant with his ability to swing and bounce. So too was Sir Richard Hadlee; he was a great exponent of swing, but at the pace Lillee bowled, he was lethal. Chuck Thommo down the other end, just to put the fear factor between them, and they were unstoppable.

Do you have any hobby horses about the modern game which you like to ride?

The crowds and Test cricket need to maintain their currency as being the blue-chip. While we’re coming into Bollywood-style cricket now, with a lot of the Bollyood guys owning teams, dancing girls, and pyrotechnics, we have to look at Test cricket. One of the things I think should happen, without actually destroying the integrity and heritage of the game, is to play Tests over four days. Split up the number of overs, so you don’t bowl more overs on any given day. You can have a day-time and a night-time session. At the MCG, for example, they have a “night” ticket.

I don’t think there’s much wrong with the 50-over game. We just play too much of it. It’s a cash-cow, there’s no doubt about it. There’s only a couple of matches that count, and they’re the semi-finals and final of the World Cup. Seriously, the rest of them ... from a player’s point of view, there’s not much kudos in saying “we won the third match, Pakistan vs Australia, in Sharjah”. I mean, sorry, but big deal.

Do you have Twenty20 vision, or are you a cricket purist?I’m a purist. I don’t dislike the other forms; I speak at a lot of conferences around the world, and my subject is change, reinvention. Played well, Twenty20 looks great. Score 170-180 off 20 overs, wow! But you see four bad shots and they’re 4/50. The ten-or-11-year-old kid suddenly thinks that’s the right way to play: wham, bam, thank you very much, tee-off on every ball, no dot balls allowed.

In Test cricket, while we’ve had blokes like Gilchrist, there aren’t a lot of guys who can successfully hit across the line at a swinging ball and be confidently successful. So, what you see is kids mirror-imaging the guys they see on telly, but you need to have a technique. It’s like a building

– you need a foundation for it to stand up, and if the foundation – or technique – is weak, then you can’t bat against a swinging ball with four slips, two gullies and a bat-pad. It’s a whole different proposition to no slips, the field spread out, an old ball on a flat wicket.

Your books were a popular part of an Aussie summer. Any all-time favourite stories from them which you still like to spin at barbeques or dinners?

Look, as a speaker, you get tagged with, “Oh, that’s a signature Max Walker story.” Year after year, I’ll try and come up with some new stuff, but then people say to me, “I brought three of my colleagues along just so they could hear this one.” And so you’re rolling out last year’s talk to

a new audience. Which is lovely. One of my signature stories is about my old man and me playing in a grand final in the middle of Tasmania on a Sunday afternoon. I was about 12 ‒ we scored 17 runs off the last ball! Only a Tasmanian could believe that was possible. It’s a long story, but I think it ended up in How To Hypnotise Chooks.

The bat handle of the only bat we had in the club had broken ‒ we were poor. So the old man goes out with a picket! We run 17, the grass is a metre high. I’m compressing the story, but the old man walks over to the opposition captain and asks, “Do you really want to know where the ball is?” He turns the picket over and nailed to the end of the picket with a dirty great big nail, is a cricket ball. “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story,” my old man said. You’re allowed a little bit of creative license, particularly at a barbeque. My old room-mate Kerry O’Keeffe turned it into an art-form!

You were painted as an out-of-control madman in Billy Birmingham’s famous The 12th Man episodes. Were you consulted before he unleashed? And what was your initial reaction to his comical character portrayals?

We weren’t consulted. Billy would sit down with a mate in front of the television, whether it was the cricket or Wide World Of Sports, over a slab of beer, and he’d try and make his mate laugh. When he did, that meant it was genuinely funny, so he took notes. Then they’d write a script, go into a sound booth and recreate the voices of Bill Lawry, Max Walker, Tony Greig, Richie Benaud. That’s how it was done ... no collaboration.It’s a form of flattery or notoriety when someone mimmicks you. I haven’t been in a commentary box for 21 years at Channel Nine, contrary to when Billy has me say “Give me my job back” ‒ that famous line in The 12th Man. It was a conscious decision for me to leave. But it’s very funny and Billy’s won more ARIAS than Johnny Farnham, Kate Ceberano and Jimmy Barnes for his very Australian take on humour. He probably doesn’t realise it, but he’s been my PR man for the last two decades. Guys still come up to me and say, “Maxy, you’re doin such a good job in the commentary box,” and I don’t have the heart to say, “Mate, I haven’t been there for 21 years!”

Related Articles

Video interview: Drinks With ... Matt Millar

Barty headlines NZ Open ambassador line-up