He was arrested for using the sport as political weapon.

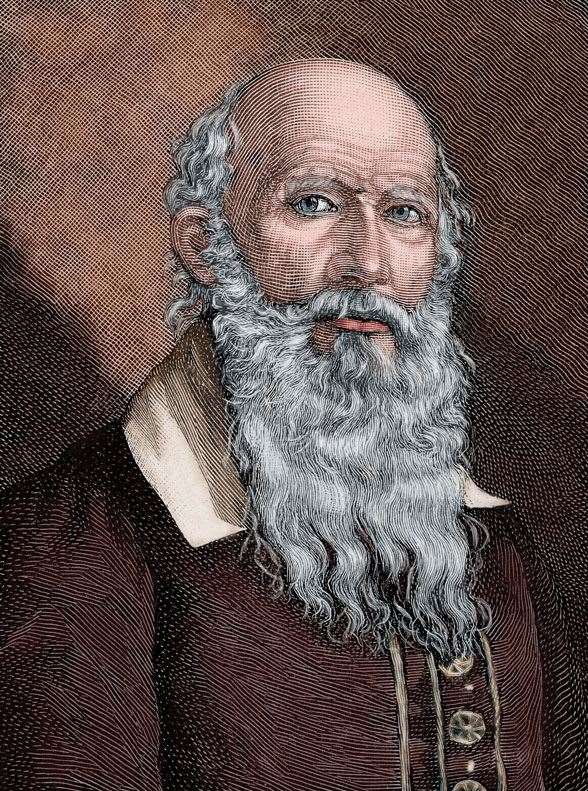

The man responsible for the development of the sport’s modern apparatus was once arrested for using gymnastics as a political weapon.

In ancient Greece, where the gymnasium was a workshop for the development of various Grecian ideas and ideals, gymnastics (from the verb gymnazo, meaning “to train naked”) was an all-encompassing activity, incorporating swimming, weightlifting, running, various throwing activities like discus, wrestling, hand-to-hand combat and other rigorous routines. You could argue that gymnastics was another word for sport.

Later, after conquering the Grecian empire, the Romans adapted these activities to the preparation of soldiers for war, but in 393 AD, the emperor Theodosius banned all gymnastic practice – and the original Olympic Games – on the pretext that it was all becoming way too corrupt. In fact, like any self-respecting dictator, Theo, jealous of the revered stars of sport whom he somehow saw as rivals to his claims to immortality, was giving free rein to his paranoia.

The glorification of the human body at the expense of spiritual life was frowned upon in the Middle Ages by the Catholic Church, which had a monopoly over all matters spiritual, and most athletic activity sank further into obscurity.

The resurrection of gymnastics was decidedly Germanic. In 1774, a Prussian, Johann Bernhard Basedow, added “gymnastics” to the curriculum at his school in Dessau, Saxony. As with all modern sport, the availability of materials and the technology to fashion them came to define the activity when Johann GutsMuths – a future Innovator subject – and Friedrich Jahn designed apparatus for gymnastics.

It was Jahn who developed the first equipment that was to narrow gymnastics to a set of routines that could be performed on that equipment: the side bar, the vaulting horse, the horizontal bar, the parallel bars. He also popularised the use of the balance beam, which was purportedly invented by GutsMuths while he was in the process of creating the more artistic form of gymnastics, which emphasised rhythmic movement and balance. In its new forms, gymnastics flourished in Germany in the 1800s.

After settling in Berlin to become a secondary school teacher, Jahn began a program he’d been pondering for some time of outdoor activity and exercise, and soon gathered a large following among adults as well, as word caught on. In no time, he became well-known enough to open his first “turnplatz” (open-air gymnasium), devoted strictly to gymnastics, in 1811, featuring his newly developed equipment. Not long afterward, many clubs were opened throughout Europe and England. By the late 19th Century, thanks to Dr Dudley Allen Sargent, who also invented a further 30 pieces of apparatus, it had caught on in the USA. In Russia in 1883, renowned playwright Anton Chekhov, along with other artists and social reformers, formed the Russian Gymnastic Federation.

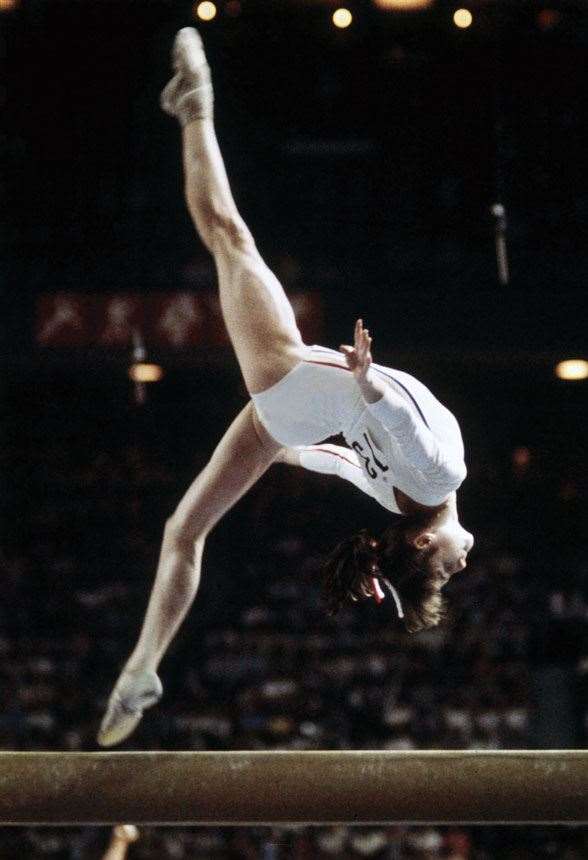

The great Nadia Comaneci. (Photo by Getty Images)

The great Nadia Comaneci. (Photo by Getty Images)Jahn, a theologian, historian and philologist, advocated and developed gymnastics as a means of restoring the spirit of his people after the abject defeats of the Napoleonic wars, thus inadvertently politicising his program of physical well-being.

Jahn was known in Germany as “Turnvater”, which means, loosely, “father of gymnastics”. However, the judgment of history has taken a nasty turn against the Turnvater. Because of Jahn’s desire to restore nationalistic pride to his folk, his Turnvereine (“gymnastic unions”) were considered hubs of political, not just athletic, activity. Indeed, many “Turners” participated in the European “People’s Spring” Revolutions of 1848. Jahn was at one time arrested and banned from entering Berlin. The ban lasted the rest of his life. The “movement”, as it came to be considered, was largely suppressed in Europe, and many “Turners”, dubbed the “forty-eighters”, emigrated to the USA, where they formed the famous German-American gymnastics clubs, became politically influential and even fought in the American Civil War. Eventually, the German “Turner movement” became involved in the process that led to German unification.

Jahn’s legacy took another unpleasant twist when his nationalistic pride, his belief in physical development and his distrust of foreigners, particularly the “Poles, French, priests, aristocrats and Jews” whom he believed had subverted his nation, were all appropriated by the Nazis in the following century. They, and their critics, installed Jahn, unfairly, as a “father” of Nazism. Yes, I know what you’re thinking: that escalated quickly! But gymnastics is like that. Because of the historical association of fitness, health and strength with “physical readiness” for war, it has always been a tool for politicians and warmongers.

Meanwhile, back in 19th Century Europe, the popularity of gymnastics spread across the continent. When the Olympic Games were resurrected in 1896, it was included, and its form, thanks to its apparatus, had become refined, until eventually it led to the beautiful spectacle we see today.

Watching gymnasts perform inspires reverence, like a hymn, or Beethoven. The only reason this paean to the human body lacks mainstream appeal is its lack of one-to-one competition that thrills most spectators. Its men are probably sport’s best physical specimens, if it’s the male ideal you’re still after. But allow us to revise, or expand, Friedrich Jahn’s legacy: the most remarkable, and ironic, thing – given its history – about gymnastics is the way it has showcased the capabilities of its women. Since their inclusion at the Games in 1920, women, with their blend of manifestly physical yet subtle beauty, have been its most famous exponents. Olga Korbut, Nadia Comaneci and Larisa Latynina have showcased what is superlative about the female athlete. Friedrich Jahn, with the apparatus he developed and the sport he championed, gave them that opportunity, and us the chance to savour it.

Related Articles

Before Barassi, there was Frank "Checker" Hughes

Will our Olympians bounce back at this year's Games?

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)