Californian-born inventor revolutionised the sport, then made revolutionary films about it.

Surfers ‒ anyone with even a passing interest in the colourful culture of surfing ‒ know the importance of George Greenough, one of the most innovative and influential practitioners of any sport, anywhere. Not only did this man profoundly affect design of the very tool of the surfer, the board, he ensured footage of surfing, and surf, would capture the popular imagination.

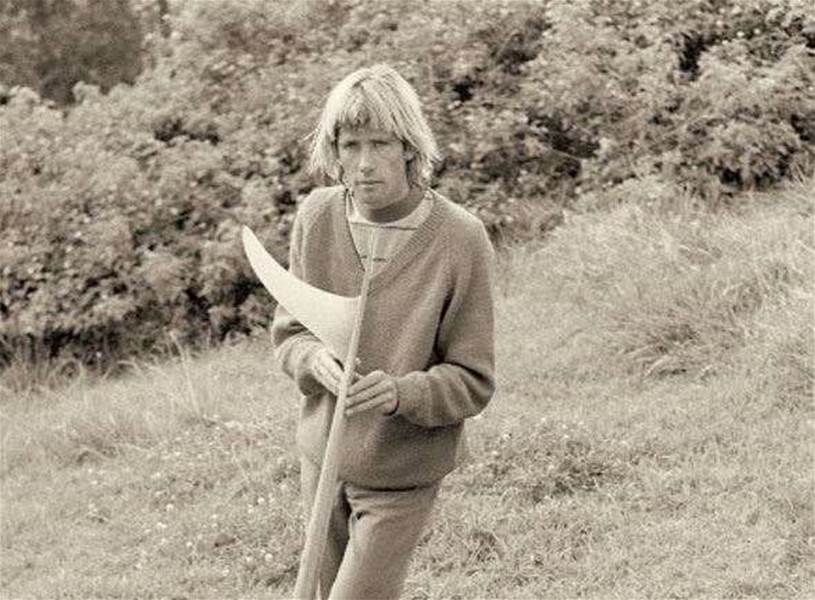

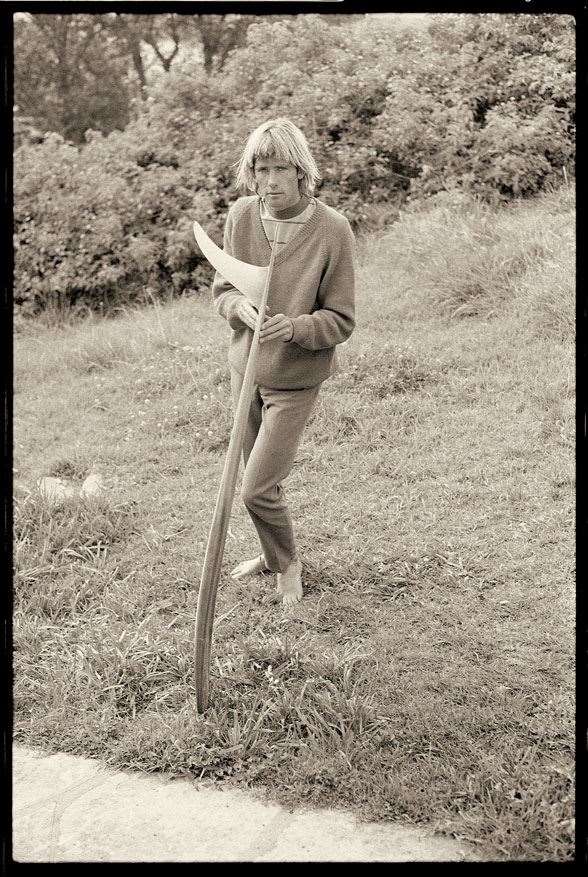

Greenough is a born inventor and visionary, an iconic surfing figure and true eccentric. Born in 1941 in Santa Barbara, California (he now lives in northern New South Wales), he’s a descendent of the great American sculptor Horatio Greenough. His wealthy family allowed him his head from the start and so George embarked, forever shoeless, on an aquatic life (he’s worn formal attire twice in his life, and flies first-class to avoid wearing shoes).

He was a curious and inventive kid, happy in the world of objects and ideas. He haunted the beautiful terrain and surfed the immaculate waves of Hollister Ranch, but was never a fan of stand-up surfing. The last time he stood on a board was 1961. At the time, Greenough found boards too unwieldy, and though he’s no misanthrope, couldn’t stand the crowds. Even today, his life is an eternal winter as he commutes between Australia and the USA, avoiding the summer throngs.

In 1962 he shaped a baby surfboard but never rode it much, instead building a kneeboard with a slightly scooped deck. Having used flexible fins long before anyone else had even considered the idea, Greenough now decided he wanted an entire board that flexed. He built a stubby kneeboard with a “spoon” shape, called the Velo, in 1965. His quiet revolution had begun, and would eventually transform the surfing world.

It was the fin that first shot him to prominence. For decades, people had been experimenting with variations to maximise control and direction. But it was Greenough who closely studied the fins of tuna and dolphins, intuitively understood their correspondence to surfing, and applied the science ‒ the physics of drag, lift, thrust and pitching moment ‒ to wave riding. The fusiform shape of the dolphin had already influenced board shape. It seemed natural that the dorsal fin that propelled the cetaceans powerfully through the water would enhance the effect. Hence George’s ideas about flexibility, of board and fin.

Riding his six-pound rig powered by an 11-inch high-aspect fin, Greenough was experiencing waves in a way no one else imagined, loading up on torque and propelling himself out of turns with incredible force.

In 1964, the great shaper Bob McTavish, another of our Innovators, happened upon Greenough powering along on his kneeboard at Noosa Heads and a vague idea that occurred to him years before suddenly roared back. It was McTavish’s eureka moment. He later wrote of that first encounter. “Look at that thrust! Carve off the top, drive back down the face, repeat. That’s it!” Short was the future. Greenough knew it all along. He never saw much value camping on the nose of a longboard, because his thing was experiencing the beauty and might of the sea.

McTavish immediately wanted to develop a stand-up board that mimicked George’s kneeboard. With Greenough, he got busy designing boards that propelled the surfer into total involvement with the wave. The result? Robert “Nat” Young became a legend. Using a longboard template, McTavish designed a stick for Young thinner than other boards, and fitted with Greenough’s bluefin tuna skeg. It’s now considered the link between the long and shortboard eras. Riding “Magic Sam”, Young blew them away at the 1966 World Championship in San Diego. The surfing world flipped on its head.

Committed curl involvement suddenly made a stagnating sport exciting again. The paradigm had shifted and was never going back, but it had shifted so unexpectedly that it took a few years for it to sink in. The tube, once a no-go, became home. Limits vanished, never to return. The days of the old-fashioned logs were numbered, except as a novelty.

Before the rest of the world really caught onto the idea of riding tubes, Greenough was already filming from inside them ‒ sometimes in the dark. Riding his short, lightweight spoons, he’d begun indulging another of his childhood passions, cameras, and adapted them in order to bring to the world the amazing spectacle he routinely enjoyed. Using his Nikonos water camera, Greenough snapped a seminal in-the-tube shot of Russell Hughes.

Incredible footage of George surfing had already appeared in The Endless Summer (1966), The Hot Generation (1968), Evolution (1969), Splashdown (1969), and Fantastic Plastic Machine (1969). Now Greenough himself experimented with movies. He turned his hand to fabricating boxes for his camera.

His point-of-view footage was an artistic revolution. Shooting with his modified 16mm camera mounted on his back, or on the nose of his spoon, carrying a rig with a battery pack and lights, he filmed inside the barrels at Rincon and other spots at night. The result was the amazing 1969 film The Innermost Limits Of Pure Fun. The film was, to use the era’s vernacular, a freak-out of torqueing wakes, curling waves and mesmeric movement. It was, as with everything Greenough did, unprecedented. On film, surfing and the surf had become tactile, hypnotic, hallucinogenic, thrilling. Members of Pink Floyd were so impressed, they contributed to his next work, Echoes (1972), a short film at 200 frames per second. They then brought out an entire album of the music of the same name.

Greenough’s board design and photography were only the beginning. He still spends his undisturbed but prolific life having fun modifying things to make them work better, or inventing them where none existed.

His vast inventory of inventions encompasses wind generators, air mats and bluewater fishing boats. He’s produced other films, sailed the South Pacific in a 39-foot backyard-constructed yacht, and built countless practical, sometimes quirky, objects. What’s more, whether on his kneeboard or his air mat, he’s considered one of the great surfers of all time. The 1978 film Fantasea featured long, enthralling sequences of him on his mat, driving deeper than anyone on a board dreamed of going.

Greenough is a still solitary figure, unmarried, animated by his ideas and love for the sea, unaffected by acclaim. Currently he’s working on a film about dolphins, and for it he’s fashioned a camera housing shaped like a baby dolphin. Monosyllabic unless consumed with an idea and presented a sympathetic ear, he occasionally contributes to surfing workshops and get-togethers, still surfs arcane spots the world over when the whim takes him, and concerns himself with cleaning up the ocean.

Related Articles

Before Barassi, there was Frank "Checker" Hughes

Will our Olympians bounce back at this year's Games?

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)